Abstract

The present paper shows that, when firms compete in a non-cooperative way on the level of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in network industries, the conventional result of the prisoner’s dilemma structure of the game in standard industries—i.e. to have social concerns is the Nash equilibrium, but it is harmful for firms’ profits—vanishes and, for sufficiently intense network externalities, the equilibrium in which both firms have social concerns is more profitable than simple profit-seeking. Moreover, we show that—when firms cooperate in choosing the profit-maximising level of social concerns—a profit-maximising CSR level does exist, provided that network effects are sufficiently strong. Therefore, in network industries, firms may obtain higher profits engaging in—cooperatively as well as non-cooperatively—CSR activities, showing that firms’ social concerns may be motivated by the owners’ selfish behaviour. Finally, a counter-intuitive result as regards consumer’s surplus and social welfare is obtained: those are always higher under competitive than cooperative choice of CSR because the level of CSR activities is higher in the former case. However, given that firms gain their largest profits with the cooperative choice of CSR, a Pareto-superior outcome is not reached.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a growing feature in several industries. As some scholars have recently noted (e.g. Kopel and Brand 2012; Becchetti et al. 2016; Fanti and Buccella 2017a, b) and the specialised documentation such as KPMG surveys (2005, 2011, 2013, 2016a) reveals, an impressive as well as constantly increasing share of companies adopts CSR reporting: while in 2005, only to mention a few, 32% of US companies, 71% of UK companies and 90% of Japanese companies adopted CSR, in 2011 about 95% of the 250 world largest companies are reporting CSR activities and, finally, in 2013, 71% of 4100 companies surveyed in 41 countries shows CSR activities. As other important examples, we can mention that 31% of the top 500 Fortune companies shows detached CSR departments (ICCA 2010) and more than 10% of total EU economy (in terms of GDP), with more than 11 millions of workers (6% of total employment) (as the EU Commission documented), take into account social objectives. Moreover, the increasing creation of Socially Responsible Investment funds supporting CSR adoption encourages the growth of the share of CSR firms. In fact, as Becchetti et al. (2016, p. 50) report “socially responsible investment funds accounted for a share of around 11% of total assets under management in the United States in 2010 (Social Investment Forum Foundation 2010) corresponding to 2.71 trillion dollars”.

On the other hand, it has been acknowledged that network industries in recent years are a fast-growing phenomenon. In such industries like mobile devices (smartphones and tablets) and related apps, and software, the utility of a particular consumer from using such devices or a software grows with the number of other mobile devices (and related apps) or software users: a positive network externality does exist.

Among the industries which have experienced an extraordinary progress in CSR activities in recent years, it is remarkable to find in a leading position precisely network industries. For instance, according to a KPMG report, the technology, media & telecommunications sector presents a 79% of the companies surveyed reporting CSR activities, the highest levels among the surveyed industries. In particular, the telecommunication subsector shows the highest rate of CSR reporting, with a 87% of the companies (KPMG 2016a, b). In addition, the Reputation Institute global CSR survey reveals that companies in network industries are chiefly engaged in CSR activities. In fact, they have a primary presence in the world’s top ten companies with regard to the best CSR reputations: Walt Disney ranks 2nd, Google 3rd, Microsoft 7th, Sony 9th and Apple 10th. Moreover, consumers perceive companies in network industries as the most socially responsible: for instance, Google ranks 1st, Microsoft 2nd, Walt Disney 3rd, Apple 7th and Intel 10th (Reputation Institute 2016).

Thus, it is natural to ask whether and how these two features—i.e. the presence of firms’ social concerns and network externality—jointly affect, through their interplay, the standard outcomes of strategic oligopolistic contexts. In particular, while the network externality is an exogenous market feature, CSR activities may be a firm’s choice variable and, thus, may strategically be used for enhancing its performance.Footnote 1

However, the literature in economics has not jointly considered the endogenous choice to undertake CSR activities and the presence of network externalities. In this paper, we develop a Cournot model in which firms may choose, non-cooperatively or cooperatively, the level of CSR interest, that is, in line with the branch of the literature above mentioned, the share of the consumer surplus to be taken into account in their objective function. In detail, the model assumes that when the owners cooperatively choose the level of engagement in CSR, they remain competitive in the product market. In other words, concerning the choice of CSR, we have a semi-collusive behaviour, an aspect of the firms’ activities the Industrial Organization (IO) literature has largely studied in other fields.Footnote 2 A key question in the paper is whether CSR is good or bad for profits. As forewarned, the traditional result is that CSR may be in the interest of one firm to extend its own market share at the expense of the rival firm, but at equilibrium CSR results in a reduction of profits. Moreover, we investigate how firms engage in CSR activities under the two (non-cooperative and cooperative) choice regimes and how the level of CSR also influences output and welfare. A number of interesting and somewhat unexpected results are derived.

In the following, we qualify the main assumptions of the paper. For simplicity, a duopoly context is assumed because, in the present multi-stage model, a larger number of firms would prevent the achievement of economically interpretable closed forms outcomes. Also, the product homogeneity allows for a more parsimonious parametric set, so favouring clear-cut interpretations of the results, while the assumption of non-durability of the product allows for a single-period analysis without the need to resort to a multi-period dynamic model. Moreover, we assume a standard demand function in which consumers are not socially concerned, differently from other models such as those of Manasakis et al. (2013) and Alves and Santos-Pinto (2008), in which consumers appreciate a socially responsible behaviour and owners decide whether to make CSR efforts in the production.

As regards the network externalities, it is implicitly assumed that (1) products are fully compatible between them, so that the overall quantity produced in the sector is relevant for the consumers, not the quantity of the specific brand/product they patronise; (2) consumers base their demand on “expected” output, that is, firms do not commit to a given level of output at the moment that consumers decide on their demand; (3) consumers form rational expectations on “expected” output. The latter assumptions are the most used in the network literature; however, in principle, it could be assumed that products are not (or only partially) compatible or firms commit themselves to a determined output or, finally, consumers form non-rational—for instance adaptive—expectations.Footnote 3 Finally, the choice of modelling the firms’ CSR behaviour as caring not only for profits but also for consumers’ surplusFootnote 4 is the most frequent in the literature (Goering 2007, 2008, 2012, 2014; Lambertini and Tampieri 2012, 2015; Brand and Grothe 2013, 2015, only to mention a few); nonetheless, we are aware that there are CSR activities which pertain to the welfare of stakeholders, such as workers, business partners, citizens and the environment, which are different from the consumers of the product.

The key findings of the paper are as follows. Under the non-cooperative endogenous choice of the level of social engagement, the equilibrium of the game is that both firms select to follow CSR rules. However, in contrast to the common wisdom, the Nash equilibrium of being CSR-type is Pareto-efficient for firms in network industries (provided that network effects are sufficiently intense): in fact, both firms are better off following CSR rules. On the other hand, in the case of cooperative choice of the level of CSR, the network effects have to be adequately intense to make CSR more profitable than profit-seeking. As regards social welfare, when the intensity of the network externalities is sufficiently low, the non-cooperative choice of CSR enhances, as expected, consumer surplus and social welfare; however, the adoption of CSR reduces profits with respect to the case of pure profit-seeking behaviour. On the other hand, when the network externalities are sufficiently intense, not only consumer surplus and social welfare but also firms’ profits—under both cooperative and non-cooperative regimes of choice of the CSR level—become larger than those under pure profit-seeking behaviour. However, since firms find more profitable to choose cooperatively than non-cooperatively a positive level of social concern, while for consumers and society as a whole the welfare is larger when firms choose the CSR level non-cooperatively rather than cooperatively, then there is a conflict of interests between consumers and society, on the one side, and shareholders, on the other side, on the regime of choice of the CSR level. Moreover, we note that the level of CSR is always increasing with the network effect under both regimes of the choice; however, the CSR level is larger under the non-cooperative than cooperative regime, although for increasing network externalities the difference tends to reduce.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. “Literature review” section presents the literature review. “The model” section introduces the model setup and analyses both the cases of non-cooperative and cooperative endogenous determination of the level of social engagement. The last section concludes outlining the future research agenda.

2 Literature review

So far, a vast and increasing literature has separately analysed the effects of CSR behaviours and network externality. As regards the former, we note that CSR is a concept which may have several interpretations, in different fields of social reality: economics, politics, social integration and ethics. In the economics’ approach—which is of course that pertinent to this work—corporation is an instrumentFootnote 5 for wealth creation whose sole social responsibility is the maximisation of shareholder value, as clearly stated by the Nobel prize Friedman (1970): “the only one responsibility of business towards society is the maximisation of profits to the shareholders within the legal framework and the ethical custom of the country”.

The maximisation of shareholder value corresponds, in the standard IO literature (e.g. Cournot competition), to a short-term profits orientation by firms in an oligopolistic context. In such a context, for instance in the basic Cournot model, apparently there would be no room for CSR in an industry at equilibrium because it leads to produce too much output from the point of view of profit-seeking shareholders and, thus, it would be unprofitable (unless the CSR activities directly or indirectly positively affect the economic costs of firms).Footnote 6 However, CSR may play an important role if viewed from one firm as strategic variable to be used in oligopolistic markets. In fact, as with the managers’ incentives towards sales analysed by the managerial delegation literature, CSR engagements may be seen by shareholders as a commitment device for their strategic choices in oligopolistic environments aiming at maximising their profits, by increasing their own market shares.Footnote 7

Therefore, to address the problems relative to the firm’s choice to become CSR-type the literature has followed various ways. On the one hand, a consistent part of the literature ascribes the firms’ engagement in CSR activities to the fact that consumers value such activities (e.g. Alves and Santos-Pinto 2008; Manasakis et al. 2013, 2014; Graf and Wirl 2014) or shareholders display social concerns (e.g. Baron 2008) or other social agents push firms towards CSR activities (e.g. Baron and Diermeier 2007). For instance, Alves and Santos-Pinto (2008), Manasakis et al. (2013, 2014) and Graf and Wirl (2014) assume that consumers are willing to pay more for a CSR firm’s products, while Baron (2008) assumes that firms may be CSR-type either because it is rewarded by consumers or because the shareholders and management value social activities (or both). Baron and Diermeier (2007) introduce political and social activists (often motivated by social or ethical concerns) as important components of the business environment who exert pressure on firms for social activities because the goal of activism is, typically, to influence firms and industry practices. Some authors such as Becchetti et al. (2016) assume that workers are the only corporate stakeholders and that there are CSR employment contracts which prevent the company from laying off workers also after a sequence of negative shocks affecting the capital accumulation.

On the other hand, other works assume that either the presence of CSR may be justified for its strategic role even if neither consumers nor shareholders particularly value social engagement (Goering 2012; Brand and Grothe 2013, 2015; Planer-Friedrich and Sahm 2016) or may be exogenously given (e.g. Goering 2007; Lambertini and Tampieri 2012, 2015; Fanti and Buccella 2017a, b) or endogenously determined but only by one firm (Kopel and Brand 2012).

Goering (2012) considers a bilateral monopoly in which either the manufacturer or the retailer can be socially concerned, and the firm’s social concern is displayed by a share of consumers surplus included in addition to the firm’s profit. That author finds that the optimal two-part tariff depends on a firms’ objective function and that CSR reduces the firm’s profit. Brand and Grothe (2013) extend the analysis to the case in which both firms are socially concerned and get two further insights into the impact of firms’ social concern on a perfectly coordinated marketing channel. Those authors show that the equilibrium outcomes are independent of the retailer’s level of social concern, because of the assumption of the perfectly coordinated marketing channel. Brand and Grothe (2015), extending their preceding work, display that firm’s social concern increases firm profit for the manufacturer as well as the retailer’s profit, mainly because CSR behaviours soften the classical double marginalisation problem. Planer-Friedrich and Sahm (2016) consider symmetric Cournot competition and show that the endogenous level of CSR is positive but such positive CSR levels imply, not unexpectedly, smaller equilibrium profits.

Goering (2007) develops a model of managerial delegation in which, as usual, managerial incentives are different from the firm’s true objective and in only one firm this objective includes in addition to profits also a share of consumer surplus. He finds that managerial incentives, however, tend to decline as the weight of the consumer surplus in the socially concerned firm’s objective function is higher because the CSR-type firm moves closer to a social planner’s objective function. Similarly, in Kopel and Brand (2012), only one firm in the considered duopoly can be socially responsible and firms can choose to hire managers. The key finding is that CSR may pay off as long as it is not used too extensively.

Making use of a Cournot duopoly model with heterogeneous products, Fanti and Buccella (2017b) analyse the firms’ strategic decision of engaging in CSR activities. The authors adopt a game-theoretic approach to show that, depending on the degree of product differentiation and firms’ level of social concern, a rich set of equilibria arises. In fact, either all firms in the industry follow CSR rules or are profit-maximising, or asymmetric and multiple symmetric equilibria are present in the industry. All those contributions find, as expected, that profits at the Nash equilibrium are damaged by CSR activities (also when the latter are endogenously determined). Remarkably, however, Fanti and Buccella (2017c) find that, in a duopoly market in which firms follow CSR activities under managerial delegation, in the Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium (SPNE) both firms are CSR-type and, in addition, the presence of CSR behaviour benefits the firms’ profitability while harms the welfare of consumers and society), a result that contrasts the conventional one under non-managerial firms.

As regards network industries, a growing number of researchers has started investigating how positive consumption externalities/network effects may reshape the findings of the standard models of imperfect competition. Following the simple mechanism of network effects pioneered by Katz and Shapiro (1985)—which is also assumed here, according to which the willingness to pay of a firm’s client increases directly with the number of other consumers. Some authors have analysed network models: Hoernig (2012), Chirco and Scrimitore (2013) and Battacharjee and Pal (2014) mainly focusing on the role of strategic managerial delegation in a duopoly, Fanti and Buccella (2016b, 2017d) mainly focusing on the role of bargaining agenda (without and with managerial delegation) in a unionised monopoly. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the only paper dealing with CSR in network industries is Fanti and Buccella (2016a). In that work, the authors examine a duopoly in a network industry in which firms are assumed to adopt CSR behaviours and show that, in contrast to the conventional result that the higher the weight on CSR the lower the firms’ profitability, the presence of network externalities may enhance the firms’ profitability. The present model follows this line of investigation.

3 The model

We assume a duopoly in which firms produce homogeneous network goods. In the spirit of Katz and Shapiro (1985), the inverse demand function (see Fanti and Buccella 2016a) is as follows,

where \( p \) is the price of goods, \( q_{i} \) and \( q_{j} \) denote the quantity of the goods produced by the two firms, \( y_{i} \) and \( y_{j} \) denote the consumers’ expectation about the firms’ sales, the parameter \( n \in [0,1) \) indicates the strength of network effects (i.e. the higher the value of the parameter the stronger the network effects) and \( a > 0 \) is a demand parameter. The standard linear production costs are assumed, for simplicity, to be zero, in that they would not play any role for the results of the paper. The firm i’s profit function is given by:

Following the recent established literature, we incorporate consumer surplus into the firm’s objective function (e.g. Goering 2007, 2008; Lambertini and Tampieri 2012, 2015; Kopel and Brand 2012; Kopel et al. 2014). This means that the firm wishes to maximise profits plus the consumer surplus (\( {\text{CS}} \)) that accrues to its stakeholders. This objective function may be parameterised through a simple combination of profits (Eq. 2) and consumer surplus, \( {\text{CS}} = \frac{{(q_{i} + q_{j} )^{2} - n(y_{i} + y_{j} )^{2} }}{2} \), where the parameter \( k_{i} \in [0,1] \) denotes the level of “social concern”.Footnote 8 Thus, the CSR objective function (\( W_{i} \)) is:

In the second stage of the game (the market game), firms decide simultaneously on their output levels \( q_{i} \ge 0 \) to maximise their objective functions \( W_{i} \). Given the CSR firm’s objective function (3), from the first-order conditions

where i, j = 1, 2 and i ≠ j, we obtain the reaction functionsFootnote 9

As usual, then we impose the additional “rational expectations” conditions, that is \( y_{1} = q_{1} \) and \( y_{2} = q_{2} \). Hence, solving the system composed by (5) and its counterpart for firm j, we obtain output and profit as a function of the CSR parameters:

Anticipating the market game equilibrium, firms may choose the level of CSR activities in a twofold way: (1) simultaneously and independently by each firm as strategic competitive variable to gain advantages over the rival firm (i.e. non-cooperative choice); (2) in a cooperative way to maximise joint profits (obviously only if a maximising level exists) (i.e. cooperative choice).

Network externalities being absent, we can easily show that in the first case, the game is a prisoner’s dilemma and, at the endogenous equilibrium, firms choose to be CSR-type with the consequence of reducing profits with respect to the profit-seeking behaviour, while in the second case it is profitable to agree on no social activity.

In the following we investigate whether this traditional wisdom is robust to the presence of network goods. Let us begin from the non-cooperative choice regime.

3.1 Non-cooperative choice of CSR parameters

3.1.1 The symmetric case: both firms engage in CSR

In the first stage of the game, each firm i anticipates quantities (6) and chooses its CSR level \( k_{i} \ge 0 \) to maximise its corresponding profit given by (7). By solving the system composed by the first-order conditions

the following reaction functions in the CSR parameters space are obtained

and at the equilibrium of the first stage the CSR level k (the upper script NC denotes the case of non-cooperative choice) that is chosen by each individual firm is given by

where \( \phi = \sqrt {17 - 20n + 4n^{2} } \) is positive and real for \( n < \frac{5}{2} - \sqrt 2 \) (whose value is above one) and, therefore, for any admissible value of \( n \in [0,1] \). It is easy to see from (10) that the equilibrium level of k is increasing with the network effect (\( n \)). By substituting (10) backwards,Footnote 10 we obtain output and profits at equilibrium

Now, we extend the above analysis by letting the firm endogenously choose whether to follow CSR rules. We show that the endogenous decisions of following CSR rules emerge as the SPNE outcome.

3.1.2 The mixed case: one firm follows CSR rule and the other one is profit-seeking

Let us consider the case that the firm \( i \) maximises the social objective function while the rival firm \( j \) maximises profits. We follow the notation of the game theory analysis in which, as known, it is standard to specify in the subscript who is the player and, in the upper script, first the strategic choice of player one, and second the strategic choice of player two. Following the standard procedure, in the second stage, the firm \( i \)’s profits as a function of its CSR parameter are given by

and, at the first stage, firm i chooses the following CSR level \( k_{i}^{{{\text{NC}},P}} \) (the upper script P stands for profit maximisation):

Substituting backward (14), both firms’ profits at the game equilibrium are given by

Now, we are in a position to conduct the following analysis. We compare firm’s profits under the two mixed cases and we investigate which rule (CSR or profit-seeking) endogenously emerges as SPNE for both firms.

First, we report here the equilibrium outcomes under profit-seeking behaviours by firmsFootnote 11:

Let us define the following profits differentials: \( \Delta \pi_{1} = \pi_{i}^{{{\text{NC}},P}} - \pi_{i}^{P,P} \) and \( \Delta \pi_{2} = \pi_{j}^{{{\text{NC}},P}} - \pi_{j}^{\text{NC,NC}} \). Notice that \( \pi_{i}^{P,P} = \pi_{j}^{P,P} \) is the same as \( \pi^{P} \) and \( \pi_{j}^{\text{NC,NC}} = \pi_{i}^{\text{NC,NC}} \) is the same as \( \pi^{\text{NC}} \); however, given that now we are investigating the SPNE of the game, we have followed the notation above. Hence, we state the following.

Result 1

In the SPNE outcome of the game both firms choose to follow CSR rules. Proof: Result 1 straightforwardly derives from the signs of the two profit differentials involved in the determination of the SPNE:

Having established that both firms endogenously choose to be CSR-type, we investigate whether and how profits, as expected, are reduced by being CSR-type. Then, the following results hold.

Result 2

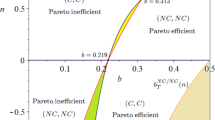

When network externalities are present and relevant (\( n \ge .74 \) ) the Nash equilibrium of being CSR-type is Pareto-efficient for firms: both firms are more profitable following CSR rules.

Proof

Let us define the following profits differential:

Result 2 straightforwardly follows from \( \Delta \pi_{3} \frac{ > }{ < }0 \Leftrightarrow n\frac{ > }{ < }.74 \).□

In contrast to the common wisdom (i.e. without the joint presence of CSR and network effects), Result 2 reveals that network externalities make CSR behaviour by both firms profitable in equilibrium. In fact, given the demand function assumed in the current model, the consumers’ willingness to pay increases with the level of expected sales of both firms. Therefore, committing to sell more due to CSR has a positive effect on profits and such effects are reinforced when both firms engage in CSR activities.Footnote 12

Remarkably, Result 2 provides an explanation of the presence of CSR behaviours in accordance with the opinion of Friedman (1970) in that firms being socially responsible may (in network industries) enhance the welfare of shareholders.

3.2 Cooperative choice of a common CSR parameter

In the case of the cooperative choice of a common level of CSR activities, at stage two of the game (the market game), firms decide simultaneously on their output levels \( q_{i} \ge 0 \) to maximise their objective functions \( W_{i} \) which now becomes:

where \( k \) is precisely the common value cooperatively decided at stage one by firms. Given the CSR firm’s objective function (19), from the first-order conditions we obtain the reaction functions

After imposing the additional “rational expectations” conditions (i.e. \( y_{i} = q_{i} \) and \( y_{j} = q_{j} \)), solving the system made of (20) and its counterpart for firm j, we get output and profits as a function of the common CSR parameter:

At the first stage of the game, firms cooperate on maximising joint profits through the choice of a uniform level of CSR activities. Defining the joint profits as

the maximisation of \( \varPi \) with respect to \( k \) leads to the following result.

Result 3

If \( n \) is sufficiently large, there is always a value of \( k \), \( k^{C} \), that maximises joint profits.

Proof

This result is proved by observing that

and

□

It is easy to observe from (25) that, when the network effect is sufficiently large, firms find optimal to semi-collude on the CSR level.

Corollary 1

Provided that n > .5, an optimal positive value of k C always does exist and this optimal value is increasing with n: the larger is the network externality, the higher is the optimal level of the sensitivity to consumer surplus by firms.

Therefore, we have two regimes: (1) n < .5, in which firms decide cooperatively not to engage in CSR activities because, in the absence of, or with weak, network effects, to follow CSR behaviours is always profit-damaging, and thus, by definition, the equilibrium outcomes are the same of those of profit-seeking firms; (2) n ≥ .5, which we denote as the cooperative regime (C). In the latter regime, the equilibrium outcomes are the following:

Now, we are in a position to compare the equilibrium outcomes under the three different regimes: profit-seeking, non-cooperative CSR and cooperative CSR.

Lemma 1

The engagement in CSR activities is the largest in the case of unilateral engagement and is higher under non-cooperative than under cooperative choice of such activities.

Proof

By simple inspection of (10), (14) and (25), the following ranking holds: \( k_{i}^{{{\text{NC}},P}} > k^{\text{NC}} > k^{C} \).

Result 4

Profits under cooperative CSR are always larger than those under non-cooperative CSR.

Proof

□

Result 5

When cooperative CSR is chosen in equilibrium (i.e. \( n > .5 \) ), it yields higher profits with respect to profit maximisation without CSR.

Proof

□

Corollary 2

The different effects on profits implied by the relationship between the intensity of the network effects, on the one side, and the regime of choice of the CSR levels, on the other side (that is, a non-cooperative or cooperative engagement in CSR activities or a pure profit-seeking behaviour), may be resumed by the following profits rankings: (i) if 0< n<.5, then \( \pi^{P} > \pi^{C} > \pi^{NC} \); (ii) if .5 ≤ n < .74, then \( \pi^{C} > \pi^{P} > \pi^{NC} \); (iii) if .74 ≤ n < 1, then \( \pi^{C} > \pi^{NC} > \pi^{P} \). In other words, a cooperative choice of the CSR level becomes profit-preferred in comparison to the pure profit-seeking behaviour for a sufficiently high level of the network effect. Moreover, if the network effect is very intense, even a non-cooperative choice for the CSR level is profit-preferred to pure profit-seeking.

Proof

By simple inspection of (12), (18) and (22).

The economic rationale for Result 5 is as follows. Because the production costs are zero in the current model, the analysis of the profits differential reflects that of the revenues differential. Defining the marginal revenues differential between cooperative CSR and pure profit maximisation as \( \Delta {\text{MR}}(n) = ({\text{MR}}^{C} - {\text{MR}}^{P} ) \), after some algebraic manipulation it is possible to obtain

An in-depth analytical inspection shows that: (1) \( \left| {\frac{{{\text{d}}q^{C} }}{{{\text{d}}n}}} \right| > \left| {\frac{{{\text{d}}q^{P} }}{{{\text{d}}n}}} \right| \), that is, the magnitude of the direct network effects’ impact on the output expansion under cooperative CSR is larger than under profit maximisation; (2) for \( n > .5 \), \( p^{P} > p^{C} \). Therefore, Result 5 is driven by the effect of the network externalities on the marginal revenues. Simple calculations show that \( \left| {\varepsilon^{ * C} (n)} \right| = 1 \), that is, the marginal revenues under collusive CSR are zero: marginal revenues are unaffected by output expansion. On the other hand, for \( n > .5 \), \( \left| {\varepsilon^{ * P} (n)} \right| = 2(1 - n) < 1 \), therefore \( \left( {1 - \frac{1}{{\left| \varepsilon \right|^{P} }}} \right) < 0 \), i.e. marginal revenues are negative: firms produce at an inelastic point of the demand function and, to expand output, the price has to decrease substantially, leading to a decrease in revenues.

Finally, some considerations on the welfare effects of the different regimes. Let us report the following expressions of consumer surplus which, in equilibrium, is \( {\text{CS}} = (1 - n)\frac{{(q_{i} + q_{j} )^{2} }}{2} \), and social welfare, defined as \( {\text{SW}} = \pi_{i} + \pi_{j} + {\text{CS}} \):

Result 6

CS and SW are always higher under non-cooperative CSR; furthermore, for \( n \ge .5 \), they are higher under cooperative CSR than under profit-seeking behaviour.

Proof

By inspection of (28)–(33), it is straightforward to establish the following ranking:

-

1.

for \( n < .5 \), \( {\text{CS}}^{\text{NC}} \left( {SW^{NC} } \right) > {\text{CS}}^{P} \left( {SW^{P} } \right) \)

-

2.

for \( n \ge .5 \), \( {\text{CS}}^{\text{NC}} \left( {{\text{SW}}^{\text{NC}} } \right) > {\text{CS}}^{C} \left( {{\text{SW}}^{C} } \right) > {\text{CS}}^{P} \left( {{\text{SW}}^{P} } \right). \) □

The rationale for this result is as follows. The engagement in CSR activities and the increasing weight ascribed to the consumers’ interests lead the firms to behave “more aggressively” in the market via output expansion (Fanti and Buccella 2017b). However, the cooperative choice of the CSR level mitigates, in equilibrium, the magnitude of the output expansion effect: the price does not excessively fall and, therefore, the firm’s profitability increases while the consumer surplus decreases with respect to the non-cooperative CSR. Given that the value of the consumer surplus in the function W dominates that of profits (a well-known result in the IO literature in the presence of the standard linear demand and technology functions adopted in the current model), and given the direct relation between output and consumer surplus, and between consumer surplus and social welfare (because under the given assumptions of the model the final effect of CSR on the social welfare as a whole is qualitatively the same of that on the consumer’s surplus), also social welfare under cooperative CSR is lower than under non-cooperative CSR. Therefore, because the firms’ cooperative choice of CSR Pareto-dominates their non-cooperative choice, a Pareto-superior regime with regard to the CSR level of engagement selection is precluded. The policy implications are direct: (1) the adoption of CSR rules in network industries should be welcomed; (2) however, if network externalities are sufficiently intense, the antitrust authorities have to watch over not only tacit-collusive agreements to reduce directly production, but also indirect collusion to reduce output via a common “social responsibility” within those sectors.

4 Conclusions

In a Cournot duopoly, the present work has shown that, when firms compete non-cooperatively on the CSR level in network industries, the conventional result of standard industries that the game has a prisoner’s dilemma structure—that is, to be socially engaged is the inefficient Nash equilibrium, because this reduces the firms’ profitability—vanishes. Indeed, though to be socially responsible is still the Nash equilibrium for any level of network effects, the equilibrium in which both firms have social concerns is more profitable than simple profit-seeking (i.e. a Pareto-efficient equilibrium for firms occurs) for a large range of the network externalities. Moreover, provided that the network effects are sufficiently strong, it is shown that when firms cooperatively select a joint profit-maximising level of social concerns there is a profit-maximising positive level of CSR activities.

Therefore, this implies that firms in network industries may get higher profits engaging in—either cooperatively or non-cooperatively—CSR activities, showing that firms’ social concerns may be motivated by the owners’ selfish behaviour. Finally, it is obtained a counter-intuitive finding with regard to consumer surplus and overall social welfare: those are always higher under competitive than cooperative choice of CSR because the CSR level is higher in the former case. However, this implies that, since the non-cooperative choice of CSR is Pareto-dominated by that cooperative one, a Pareto-superior regime of choice of the CSR level is prevented. As a consequence, a government whose objective is to improve the overall welfare should favourably consider the presence of CSR activities in network industries. Nonetheless, if network externalities are adequately intense, the antitrust authorities have to watch over both tacit-collusive agreements to cut directly production and indirect collusion to reduce output via the decision of adopting a common CSR rule within those sectors. To delimit honestly the real-world implications of the present model, we note that the results must be interpreted with caution in view of the specific hypotheses assumed (although several assumptions are quite common in the IO literature).

As future line of research, those results call for a robustness check under different model specifications, relaxing the hypotheses assumed in this paper. First, it would be interesting to introduce some forms of asymmetry in the model. For instance, a suitable line of research can be an analysis contemplating product differentiation and the interaction of network externalities with product differentiation to verify the survival of the present results. Intriguing could be an investigation of the case in which each company considers only the network effects limited to their expected sales. Asymmetry would also call, possibly, for an asymmetric selection of CSR levels when firms are allowed to cooperate.Footnote 13 Second, other hypotheses, such as price competition, the firms’ output commitment to precise levels of production rather than the consumers’ output expectations, the presence of managerial delegation,Footnote 14 different production technologies (such as convex costs) and endogenous costs (such as unionised labour costs) should be also investigated.

Notes

It should also be noted that other reasons for the big ICT firms to be almost all involved in CSR practices may be traced out in (1) a “signal” effect due to the CSR: in fact, being in big ICT network and having relevant lock-in effects, the firms’ adoption of CSR is a clear signal to affect buyers’ expectations and demand. Thus, “behaving badly” (not following CSR protocols) and losing one consumer from the installed base represents a double penalty to the firm: one is the output unit lost, the other is the lower utility, and therefore, willingness to buy/demand by those who will evaluate the purchase in the future; (2) their size and the global nature of their market, which imply bigger budgets for communication strategies and corporate identity, among which CSR is one of the most recent trends. We thank an anonymous referee for having pointed out these effects.

In this regard, the paper relates to the literature on semi-collusion, in which firms compete in a dimension, in general, price or quantity because competition rules impede companies to collude (explicitly) in the market for final products and services; however, firms may collude on other dimensions, because semi-collusion may turn out to be profitable for firms. For recent contributions, see e.g. Foros et al. (2002) on collusion on investment with respect to the product quality and Dewenter et al. (2011) on collusion on advertising.

In fact, the rational expectations hypothesis, although simple and clear, may make it difficult—as an anonymous referee argues—to explain all those activities which real-world firms engage in to manage consumers expectations (and CSR may be one way to affect consumers expectations about the quantity and quality of the product as well).

Note that, in this case, the choice of adopting a CSR protocol becomes qualitatively similar to the choice of a strategic managerial delegation à la Vickers (1985) because caring about consumer welfare, which is dependent upon output (due also to network effects), is equivalent to hiring a manager with an objective function biased (away from profits) towards output/market share. Notice, however, that this similarity depends on the assumption of non-durable goods. In fact, in the case of durable goods, the firms’ CSR activities could consist in lowering waste and saving in the use of natural resources, which would imply an increase of the consumers’ surplus without affecting output. The latter case corresponds to several appliances offered by ICT firms (for instance, Apple sells smartphones, Intel sells CPU, Microsoft sells software, which are undoubtedly durables).

Garriga and Melè (2004) provide an interesting survey of the different interpretations of CSR.

In the standard literature—and also in the current work—the production costs of the firm are independent of the social concern level of the firm itself. If this does not apply, then whichever investment in social demands that would cut firm’s costs would, at the same time, generate a shareholder value’s increase, as Friedman (1970) analyses (cited in Garriga and Melè 2004, p. 53): “It will be in the long run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community or to improving its government. That makes it easier to attract desirable employees, it may reduce the wage bill or lessen losses from pilferage and sabotage or have other worthwhile effects.” In addition, the literature has identified that CSR activities may conceivably improve the firms’ profitability via different channels: for example, by reducing the rates of turnover and operating costs, enhancing efficiency, attracting more skilled, loyal and motivated employees (e.g. Nun and Tan 2010). Nonetheless, without the above-mentioned motives, the expected result is that CSR activities always reduce the firm’s profit and thus the shareholders’ value at the industry equilibrium.

Moreover, as suggested by an anonymous referee, we note that, although beyond the assumptions of the present paper, there are other intuitive reasons for firms operating in sectors where network effects are large to adopt more frequently CSR, such as the consideration of a longer term perspective and the concern for consumers’ welfare. In fact, both affect the expectations of potential buyers about the firm’s future behaviour, its subsequent market share and its long-term success (and network size).

In principle, the CSR parameter can range between \( k_{i} \in [0,1] \). However, as will be shown [see Eq. (22)], in equilibrium, the CSR parameter ranges in the interval \( k_{i} \in [0,.5] \) to guarantee the non-negativity condition on profits.

Notice that the reaction functions are, as expected, negatively sloped, that is products are perceived by firms as strategic substitutes (i.e. network effects do not affect the slope of the reaction functions).

Note that the level of k given by (10) would be the same also in the case of positive constant marginal costs, and thus, with linear demand and costs, the equilibrium level of CSR is independent of consumer’s preferences and technology.

These results have recently become standard in the literature on network industries and are drawn from Buccella and Fanti (2016) to whom we refer for more details.

We thank an anonymous referee for having suggested this observation.

We are extremely thankful to an anonymous referee for having suggested this line of research.

Managerial delegation in the presence of CSR activities (without network externalities) is the subject of ongoing research. Preliminary results (not published) show that the presence of sufficiently large firms’ social concerns modifies the conventional results of the managerial delegation game, eliminating its prisoner’s dilemma structure and, therefore, allowing for a win–win outcome for both firms. The suspicion is that, also with network externalities as described in this paper, it should be more profitable to delegate quantity choices to (sale-oriented) managers for both firms in equilibrium for some levels of CSR engagement. We thank an anonymous referee for raising this observation.

References

Alves C, Santos-Pinto L (2008) A theory of corporate social responsibility in oligopolistic markets. Cahiers de Recherches Economiques du Departement d’Economerie et d’Economie politique (DEEP) 09.04. Université de Lausanne, Faculté des HEC, DEEP

Baron DP (2008) Managerial contracting and corporate social responsibility. J Public Econ 92(1–2):268–288

Baron DP, Diermeier D (2007) Strategic Activism and Nonmarket Strategy. J Econ Manag Strategy 16(3):599–634

Becchetti L, Solferino N, Tessitore ME (2016) Corporate social responsibility and profit volatility: theory and empirical evidence. Ind Corp Change 25(1):49–89

Bhattacharjee T, Pal R (2014) Network externalities and strategic managerial delegation in Cournot duopoly: is there a prisoners dilemma? Rev Netw Econ 12(4):343–353

Brand B, Grothe M (2013) A note on “corporate social responsibility and marketing channel coordination”. Res Econ 67(4):324–327

Brand B, Grothe M (2015) Social responsibility in a bilateral monopoly. J Econ 115:275–289

Buccella D, Fanti L (2016) Entry in a network industry with a “Capacity-Then-Production” coice. Seoul J Econ 29(3):411–429

Chirco A, Scrimitore M (2013) Choosing price or quantity? The role of delegation and network externalities. Econ Lett 121:482–486

Dewenter R, Haucup J, Wentzel T (2011) Semi-collusion in media markets. Int Rev Law Econ 31:92–98

Fanti L, Buccella D (2016a) Network externalities and corporate social responsibility. Econ Bull 36(4):2043–2050

Fanti L, Buccella D (2016b) Bargaining agenda and entry in a unionised model with network effects. Ital Econ J 2(1):91–121

Fanti L, Buccella D (2017a) The effects of corporate social responsibility on entry. J Ind Bus Econ 44(2):259–267

Fanti L, Buccella D (2017b) Corporate social responsibility in a game theoretic context. J Ind Bus Econ 44(3):371–390

Fanti L, Buccella D (2017c) Corporate social responsibility, profits and welfare with managerial firms. Int Rev Econ 64(4):341–356

Fanti L, Buccella D (2017d) Manager-union bargaining agenda under monopoly and with network effects. Manag Decis Econ 38(6):717–730

Foros O, Hansen B, Sand J (2002) Demand-side spillovers and semi-collusion in the mobile communications market. J Ind Compet Trade 2(3):259–278

Friedman M (1970) The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, Sept 13th, pp 32–33, 122–126

Garriga E, Melè D (2004) Corporate social responsibility theories: mapping the territory. J Bus Ethics 53:51–71

Goering GE (2007) The strategic use of managerial incentives in a non-profit firm mixed duopoly. Manag Decis Econ 28:83–91

Goering GE (2008) Welfare impacts of a non-profit firm in mixed commercial markets. Econ Syst 32:326–334

Goering GE (2012) Corporate social responsibility and marketing channel coordination. Res Econ 66(2):142–148

Graf C, Wirl F (2014) Corporate social responsibility: a strategic and profitable response to entry? J Bus Econ 84(7):917–927

Hoernig S (2012) Strategic delegation under price competition and network effects. Econ Lett 117(2):487–489

International Congress and Convention Association (ICCA) (2010) Statistics report 2010. www.iccaworld.com/dcps/doc.cfm?docid=1246

Katz M, Shapiro C (1985) Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. Am Econ Rev 75(3):424–440

Kopel M, Brand B (2012) Socially responsible firms and endogenous choice of strategic incentives. Econ Model 29(3):982–989

Kopel M, Lamantia F, Szidarovszky F (2014) Evolutionary competition in a mixed market with socially concerned firms. J Econ Dyn Control 48:394–409

KPMG (2005) KPMG International Survey of Corporate responsibility reporting 2005. https://commdev.org/userfiles/files/1274_file_D2.pdf

KPMG (2011) KPMG International Survey of Corporate responsibility reporting 2011. https://www.kpmg.com/PT/pt/IssuesAndInsights/Documents/corporate-responsibility2011.pdf

KPMG (2013) KPMG Survey of Corporate responsibility reporting 2013. https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/08/kpmg-survey-of-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2013.pdf

KPMG (2016a) Corporate responsibility reporting in the Technology, Media & Telecommunications sector. April, 2016. https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/06/survey-sector-supplement-tmt.pdf

KPMG (2016b) Corporate responsibility reporting in the Telecom sector. July 2016. https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2016/08/corporate-responsibility-reporting-telecom-sector.pdf

Lambertini L, Tampieri A (2012) Corporate social responsibility and firms’ ability to collude. In: Boubaker S, Nguyen DK (eds) Board directors and corporate social responsibility. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 167–178

Lambertini L, Tampieri A (2015) Incentives, performance and desirability of socially responsible firms in a Cournot oligopoly. Econ Model 50:40–48

Manasakis C, Mitrokostas E, Petrakis E (2013) Certification of corporate social responsibility activities in oligopolistic markets. Can J Econ 46:282–309

Manasakis C, Mitrokostas E, Petrakis E (2014) Strategic corporate social responsibility activities and corporate governance in imperfectly competitive markets. Manag Decis Econ 35:460–473

Nun CW, Tan G (2010) Obtaining intangible and tangible benefits from corporate social responsibility. International Review of Business Research Papers 6(4):360–371

Planer-Friedrich L, Sahm M (2016) Strategic corporate social responsibility. University of Bamberg, Mimeograph

Reputation Institute (2016) 2016 Global CSR RepTrak 100. https://www.reputationinstitute.com/2016-Global-CSR-RepTrak.aspx

Social Investment Forum Foundation (2010) 2010 Report on socially responsible investing trends in the United States. http://www.ussif.org/files/Publications/10_Trends_Exec_Summary.pdf

Vickers J (1985) Delegation and the theory of the firm. Econ J 95:138–147

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

We are extremely grateful to the Editor, Luigino Bruni, and the three anonymous referees for their valuable comments and suggestions that have substantially enhanced the clarity and quality of the paper. All remaining errors are, of course, our sole responsibility. The usual disclaimers apply.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fanti, L., Buccella, D. Profitability of corporate social responsibility in network industries. Int Rev Econ 65, 271–289 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-018-0297-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-018-0297-8