Abstract

A growing area of marketing research has surfaced in the past 20 years at the nexus of marketing and sustainability. However, a review of marketing literature shows that this field lacks conceptual and theoretical clarity. This article reviews research published on sustainability from 25 leading marketing journals between 1997 and 2016. It examines how theories used to frame sustainability in marketing literature have evolved. Additionally, no unified definition for sustainability exists in current marketing literature. To fill this void, the author proposes a new, holistic definition of sustainability in marketing, coined “sustainable marketing,” which is unique to the marketing discipline. Through presenting the GREEN Framework of Sustainable Marketing, the author conceptually and theoretically clarifies, unifies, and extends the current research. Finally, the systematic review explores implications for theory and practice and offers researchers, practitioners, and policymakers many opportunities for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

The past two decades have seen a rapid growth in marketing research at the nexus of marketing and sustainability. This area of research provides opportunities for marketing researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to study sustainability questions related to climate change, consumption and behavior, advertising, message framing and communication, branding, marketing ethics, environmental concerns, business practices, public policy, innovation, and macromarketing, among others. The research on sustainability published in marketing literature has expanded significantly, from seven articles published in 1997 to 37 articles published in 2016. However, the literature lacks conceptual and theoretical clarifications on how sustainability is framed in marketing research. It also fails to examine how theories used to frame sustainability in marketing literature have evolved and what opportunities exist for future research. The field’s growth has fragmented the definition of sustainability, causing researchers to borrow and create new definitions. Inconsistent definitions can lead to unreliable approaches when framing research questions and analyzing findings. No review of studies, definitions, or models has yet unified this fragmentation. This fragmentation has resulted in a decline in conceptual analysis (Yadav 2010) and a call for more conceptual research (MacInnis 2011).

This review examines the research at the nexus of marketing and sustainability and strives to unify the marketing field’s fragmented approaches to understanding sustainability. To achieve this goal, this systematic review uses theoretical frameworks from the foundational marketing roots of the theory of exchange (Alderson 1957; Bagozzi 1975, 1978), the four fundamental explananda of marketing (Hunt 1983), the American Marketing Association (AMA) definition of marketing (AMA 2017), and an integrated analysis (MacInnis 2011) of the 13 most used theories and models.

During the past 20 years (1997–2016), researchers have produced a research base (228 articles) that is large enough to analyze. Researchers have written numerous review articles that focus on theories or marketing areas related to sustainability. For example, Connelly, Ketchen, and Slater’s (2011) “theoretical toolbox” of research ideas presented nine specific theories that marketing researchers could use in future studies on sustainability, while Kumar et al. (2013) described 16 years (1996–2011) of literature published on sustainable marketing strategy. Chabowski et al. (2011) reviewed literature published between 1958 and 2008 and recommended five business-related areas for future research on sustainability. Gordon et al. (2011) developed a framework for sustainable marketing that uses three marketing sub-disciplines: green marketing, social marketing, and critical marketing. In contrast to these previous review studies, this review examines the evolution of theory and substantive thought in the field by examining how research on sustainability published in marketing journals has changed over the past 20 years. By locating, appraising, and synthesizing (Dickson et al. 2014) the published research, this study crafts a definition of sustainable marketing and proposes a framework to help guide marketing researchers and practitioners with research in these important areas.

This review’s contribution to marketing knowledge is fivefold. First, it presents a unique story of how research published on sustainability uses existing theories. Second, the review proposes a definition of sustainability specific to the marketing discipline: “sustainable marketing.” Third, by grounding sustainable marketing in foundational marketing thought and the 13 most used theories and models, the review contributes to the theory of exchange (Alderson 1957; Bagozzi 1975, 1978) and the fundamental explananda of marketing (Hunt 1983). Fourth, this review proposes five sustainability principles through the GREEN Framework of Sustainable Marketing. GREEN is an acronym for a Globalized marketplace of value exchange, Responsible environmental behavior for current and future generations, Equitable sustainable business practices, Ethical sustainable consumption, and Necessary quality of life and well-being for both consumers and stakeholders. This review unifies past research to provide a macro-level foundation for future theory development and to progress the discovery—justification continuum (Yadav 2010) at the nexus of marketing and sustainability. Finally, the systematic review concludes by providing researchers, practitioners, and policymakers with new opportunities for future research.

The review is organized into six sections. First, the review describes the method by which journals and research articles were selected. Second, it examines the fragmented past of research on sustainability published in marketing literature. Third, the review proposes a new definition of sustainable marketing that treats the concept of sustainability holistically and acknowledges all marketing stakeholders. Fourth, the review analyzes the 13 most used theories and models to form five sustainability principles that ground sustainability in marketing research: the GREEN Framework of Sustainable Marketing. Finally, the review concludes by identifying opportunities for future research.

Method of discovery and selection

This review investigates research between 1997 and 2016 in the top 25 marketing journals, as ranked by Thomson Reuters (2016). It uses Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science Social Science Index to locate articles on sustainability published in marketing literature. Title words searched include sustainability, sustainable, environmental, and green. The search produced 464 articles with one or more key terms in their titles. Further analysis applied to the abstracts and content identified 228 articles relevant to sustainability within the context of this study. Broadly construed, research on sustainability in this study seeks to improve the environment, economy, and society (Elkington 1994). Table 1 displays the distribution of the 228 articles on sustainability published in the top 25 marketing journals. Appendix 1 details the systematic review methodology and process used to search, screen, extract, and synthesize (Transfield et al. 2003) the articles. Only studies with in-text citations are included in the reference list; however, an online Appendix II lists all 228 articles analyzed for this systematic review.

Sustainability in marketing literature: a fragmented past

There is no clear definition of sustainability in marketing. In marketing literature, some researchers define sustainability as an environmental concept, while others define it more holistically, with definitions borrowed from the Brundtland Commission (1987) and the triple bottom line (Elkington 1994). For this review, “sustainable” is defined as more than just the staying power of a resource; it is a broader, holistic, environmental idea. Identifying how marketing researchers define sustainability is central to framing questions, analyzing findings, and interpreting solutions. While not explicitly stated as “sustainability,” Peter Drucker is one of the first researchers in marketing and management to explore ideas of sustainability. Drucker (1955) concluded that management “has to consider the action [that] is likely to promote the public good, to advance the basic belief of our society, to contribute to stability, strength, and harmony” (p. 382). He also argued that firms should produce a benefit for society (Drucker 1974). During the 1970s and 1980s, researchers explored sustainability questions mainly from an environmental focus, such as environmental considerations for new product development (Varble 1972) and environmental impacts of changes in consumption styles (Uusitalo 1982).

In 1997, Kilbourne, McDonagh, and Prothero published a seminal article theorizing that sustainable consumption is a macro-level idea. They argued that “the principles of micromarketing may have decreased consumers’ QOL [quality of life] and contributed to the deterioration of our natural environment” (p. 20) and that to explore sustainability effectively, researchers must investigate questions from a macro-societal level. Since 1997, more research on sustainability has been published using a larger, macro-level focus, to include technological, political, economic, ethical, and environmental ideas (Elkington 1994; Lim 2016).

In the early 2010s, marketing journal editors started to create sustainability special issues, prompting a substantial increase in research on sustainability. Between 1997 and 2010, fewer than 10 articles were published yearly in the leading 25 marketing journals; however, with the special sustainability issue of the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science in 2011, the number of articles published yearly increased to 23. The Journal of Macromarketing published two special issues in 2012 and 2014, respectively, and the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing published a special environmental issue in 2017. Since 2011, over 20 articles have been published yearly, with 37 articles published in 2016. With the increase of marketing articles published on sustainability, research has become fragmented. First, there is a lack of conceptual clarification, including what definition of sustainability researchers borrow or create, how they frame their research, and what theories and models they use. Second, although articles have been published in 23 of the top 25 marketing journals, most are published in only a few of the journals (Table 1). If researchers are not reading the few journals that publish most of these articles, they will not be exposed to the breadth and depth of this research domain.

The three most used definitions for sustainability in marketing literature (Table 2) derive from the Brundtland Commission (1987), the triple bottom line (Elkington 1994), and environmental concern. In over half of the articles, researchers borrow at least one of these definitions. Sustainability can be defined as sustaining the status quo, which may harm the environment, or improving the environment and society for future generations (Brundtland Commission 1987). Table 2 categorizes sustainability by definition type: either environmental or holistic. Environmental definitions focus solely on environmental measures, whereas, holistic definitions focus on all-inclusive measures. Holistic definitions include, but are not limited to, the triple bottom line and the Brundtland Commission definitions (Table 3).

Without a consistent definition of sustainability, some marketing researchers use an environmental framework while others use a holistic framework. Early on, marketing researchers framed sustainability through environmental claims, activism, behavior (McCarty and Shrum 2001), green marketing (Roberts and Bacon 1997), and eco-performance (Arquitt and Cornwell 2007), or as “environmental concern” (e.g., Pujari et al. 2004). Later, researchers framed sustainability more holistically (Chan et al. 2015). However, more than half of the research is published using the narrower, environmental definition (Table 2). This fragmentation in marketing literature causes definitional and conceptual confusion in the field.

There is also fragmentation between critical-oriented and solution-oriented positioning. Most articles on sustainability published in marketing research emphasize a critical questioning of sustainability. These normative articles emphasize that sustainability is a problem (Fuller and Ottman 2004), consumers must change their behaviors (Minton and Rose 1997), firms must be sustainable to be competitive (Peterson and Lunde 2016), and sustainability can have profound impacts on society (Kilbourne 2004). Even though many studies critically question sustainability and its impacts on the environment, few studies provide “how-to” solutions for implementing sustainable action. This fragmentation in positioning makes it difficult for marketing researchers to prescribe potential objectives and solutions for marketing.

Finally, during the past 20 years, marketing researchers have used a range of theories and models to frame sustainability. The 228 articles reviewed for this study used 158 unique models or theories. In total, the articles used theories and models 260 times. In nine of the articles, researchers did not utilize theories, and in 12 of the articles, they created their own models. Table 4 lists the 13 most popular theories and models. These 13 theories and models were utilized 110 times and accounted for 69.6% of all theories and models used. If an article used two theories, for instance, the article was counted twice, once under each theory. Fragmentation causes a lack of theoretical clarification of how theory evolves and a lack of conceptual clarification of how to define sustainability in marketing research. The next section examines how researchers borrow definitions of sustainability and offers a new definition of sustainability for marketing research as “sustainable marketing.”

Defining sustainability in marketing

The many definitions of sustainability

Table 3 presents a few of the definitions of sustainability that researchers have used in marketing literature. Besides the Brundtland Commission (1987) definition and the triple bottom line (Elkington 1994) definition, marketing researchers used 110 other definitions of sustainability. This fragmentation creates misleading research results, causes confusion about how sustainability is defined in marketing literature, and leads to questions about how research on sustainability extends theory, among others. This is not just a marketing problem; other disciplines, such as the natural sciences, psychology, sociology, and geography, also face confusion and misinterpretation when defining, analyzing, and interpreting sustainability (Williams and Millington 2004).

In marketing research, the most commonly used definition of sustainability is borrowed from the Brundtland Commission; however, this definition more accurately defines sustainable development. The Brundtland Commission (1987) asserts that sustainable development is the “development that meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (p. 24). Researchers and practitioners have criticized the wording of this definition (Farley and Smith 2014). For instance, how does this definition relate to marketing and its role in the exchange of value (Alderson 1957)? This definition does little to help define the roles of consumers, firms, and marketplaces in lowering harm to the environment and acting as ethical and equable stewards of exchange.

The second most used definition is the triple bottom line. The triple bottom line defines sustainability at the intersection of economic, social, and environmental dimensions (Elkington 1994). When communicating sustainability, many firms and consumers think of environmental (or green) initiatives, like solar panels, recycling programs, or public transportation (Farley and Smith 2014). Yet, this is only one dimension; sustainability strategies should meet all three dimensions. Ozanne et al. (2016) scrutinized the tensions at the intersection of the triple bottom line and the role of public policy arguing that organizations often face tensions between the triple bottom line, institutional pressures, and policy concerns. Lim (2016) extended the triple bottom line by proposing two more dimensions—ethics and technology—arguing that the world today can only sustainably exist if consumers are doing the “right thing” and using technology wisely. A major weakness of the triple bottom line used in marketing studies is that it has no central focus on the marketing discipline: exchange of value (Alderson 1957).

Finally, many commonly used definitions of sustainability are related to environmental concerns for the planet. Researchers used environmental concern as a definition more often during the earlier years of this review (Table 2); holistic definitions have been used more recently. Additional examples of environmental/green definitions are shown in Table 3. A major criticism of these definitions is that environmental/green definitions do not encompass the holistic nature of sustainability.

A new definition of “sustainable marketing”

Because of the many—and often criticized—definitions of sustainability, this review proposes a new definition of sustainability to be used by marketing researchers: “sustainable marketing.” The Brundtland Commission and the triple bottom line definitions are too broad, and the green/environmental definitions are too narrow. Other researchers define sustainability in different ways, for example, as sustainable consumption, sustainable supply chain management, environmental concern, green advertising, green marketing, and green commodity, among others (Table 3). While sustainable consumption, for instance, is holistic in its sustainability emphasis, it only pertains to consumers. When analyzing the themes of various other definitions, past researchers have used definitions that include firms lowering their harm to the environment (e.g., Richey Jr. et al. 2014; Soyez 2012; Xie et al. 2015); providing for future generations (e.g., Hensen et al. 2016; Newman et al. 2012; Brundtland Commission 1987); implementing environmental, economic, and social stability (e.g., Elkington 1994; Olsen et al. 2014; Oruezabala and Rico 2012); reducing the impact of the firm’s activities (e.g., Borland 2009; Hult 2011; Richey Jr. et al. 2014); and encouraging green behaviors to achieve QOL and well-being (e.g., Karmarkar and Bollinger 2015; Newman et al. 2012). The definitions that researchers use or create do little to help define sustainability grounded in the foundations of marketing thought. This review creates a definition of sustainability specific to the marketing discipline, using the term “sustainable marketing.” Some researchers have already coined the term sustainable marketing (e.g., Gordon et al. 2011; Lim 2016; Mitchell et al. 2010). However, most current definitions define sustainable marketing from a business or a consumer perspective, not from a holistic perspective; therefore, a new definition is presented.

-

Sustainable marketing is the strategic creation, communication, delivery, and exchange of offerings that produce value through consumption behaviors, business practices, and the marketplace, while lowering harm to the environment and ethically and equitably increasing the quality of life (QOL) and well-being of consumers and global stakeholders, presently and for future generations.

This definition is partly derived from the AMA (2017) definition of marketing, Alderson (1957) and Bagozzi’s (1975, 1978) theory of exchange, and the past definitions and theoretical insights reviewed in the 228 marketing articles published on sustainability. According to the AMA, marketing is the “activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large” (AMA 2017). While some argue that marketing and sustainability are two independent areas of research (Peattie and Peattie 2009), others argue that marketing with sustainability underpinnings can benefit all stakeholders (Ferdous 2010).

There are other constructs of sustainability that researchers use, such as sustainable development, green, and sustainable consumption; however, the proposed definition is unique to the marketing discipline. It holistically incorporates these areas: 1) the exchange of value between consumers, firms, and society; 2) which are ethical and equitable; 3) to increase QOL and well-being of all stakeholders involved; 4) that lowers harm to the environment, and 5) applies to present and future generations. This definition may not work for other disciplines; however, it suffices for marketing researchers and practitioners studying sustainability.

Sustainable marketing is based on the strategic exchange of value between consumers, firms, and society (Mittelstaedt et al. 2014) when they exchange products, services, and ideas. Researchers trace marketing exchange to scholars such as Alderson (1957) and Bagozzi (1975, 1978). Alderson (1957) examined the dyadic relationship between two entities; Bagozzi (1975) explored exchange as a complex “system of mutual exchange between at least three parties” (p. 33). Gundlach and Murphy (1993) extended the theory of exchange, arguing that exchange involves “doing the right thing” for society. Finally, Polonsky (2011) suggested that green marketing is an “exchange process… [in which] exchange considers and minimizes environmental harm” (p. 1311). While Alderson and Bagozzi were most likely not linking exchange to sustainability, the root of what these researchers were attempting to accomplish is to create a value of exchange that is socially, environmentally, and economically ethical and equitable for stakeholders. Sustainability has a strong focus on these seminal concepts of marketing exchange. The proposed definition captures the idea that sustainable marketing is a complex exchange of value among all stakeholders.

The proposed definition is rooted in the exchange of value. For instance, consumers must see the value in behaving sustainably, such as paying more for sustainable products, sorting their recycling, or researching which firms are marketing sustainable products ethically versus greenwashing (Ertz et al. 2016). When firms are marketing sustainability to customers, they must also deliver value at the business level (Mittelstaedt et al. 2014). Firms and their employees must see the value in acting sustainably, such as through their business practices, role in the community, green strategies, and marketing sustainable products and services. When the value outweighs the cost, and often, creates a competitive advantage in the marketplace (Hult 2011), there is a sustainable exchange of value. Finally, there needs to be an exchange of value between firms and consumers with the marketplace. The marketplace is anywhere where exchange occurs, which includes the macro-level exchanges between cities, countries, and governments, as well as the micro-level exchanges between one buyer and one seller. The market system of regulations, policies, and competition influence the marketplace. A sustainable marketplace will influence if and how firms market sustainable products and services and if and how consumers behave sustainably (Phipps and Brace-Govan 2011). In turn, sustainable firms and consumers will influence the sustainable practices of the marketplace (Leary et al. 2014).

The proposed definition also states that this exchange of value must lower harm to the environment based on a predefined benchmark (Polonsky 2011). This benchmark can be set at the consumer level, such as using fewer kilowatts of electricity than the previous year, set at the business level, such as using 50% more recyclable materials in creating their products, or set at the marketplace level, such as governments passing regulations on carbon emissions. Finally, sustainable marketing must improve the QOL and well-being of consumers and global stakeholders (Gordon et al. 2011). Sustainable marketing initiatives must be in the best interest of consumers. If a sustainability initiative is marketed in a way that, for instance, lowers the QOL for consumers, jeopardizes their safety, and/or creates a state of discomfort in their lives, consumers will most likely not behave sustainably (Dolan 2002). Firms practicing sustainable marketing must make strategic decisions that will be ethical and equitable (fair and impartial) for all stakeholders. Therefore, sustainable marketing is an interlocking exchange of value between the environment, economics (firms and consumers), and society (the marketplace) (Elkington 1994) that lowers harm to the environment (Polonsky 2011) for current and future generations (Brundtland Commission 1987).

Theoretical background

The past 20 years of research illustrates that marketing researchers can make substantive and theoretical contributions to research on sustainability. This review later proposes a GREEN Framework of Sustainable Marketing grounded on three foundational areas of marketing thought: the theory of exchange (Alderson 1957; Bagozzi 1975, 1978), the four fundamental explananda of marketing (Hunt 1983), and the evolution of 13 theories and models.

Marketing is rooted in the theory of exchange (Alderson 1957). Bagozzi (1974) later concurred that marketing’s goal is “to explain and predict the exchange relationship” (Hunt 1983, p. 10). Bagozzi (1979) proposed foundations for a formal theory of marketing exchange that would lead to a general theory of marketing. Many other researchers, including Alderson (1965) and Bartels (1968) have also attempted to create a general theory of marketing. Hunt (1983) created four fundamental explananda of marketing exchange, and later he questioned what ‘marketing is’ as a discipline (Hunt 1992). The proposed definition and framework are rooted in this complex relationship of value exchange (Bagozzi 1975).

Hunt’s (1983) four “fundamental explananda of marketing” are influential to marketing research. As an extension of the theory of exchange, the four explananda focus on 1) the behaviors of buyers in the exchange relationship, 2) the behaviors of sellers in the exchange relationship, 3) the institutional framework facilitating those exchanges, and 4) the consequences of those exchanges on society. Since 1983, the four explananda have been used extensively as a foundation of marketing thought, such as in Vargo and Lusch’s (2004) service-dominant logic and Hunt and Morgan’s (1994) research in relationship marketing. This review uses the four fundamental explananda of marketing to ground five sustainability principles.

This review analyzes the 13 most used theories and models that marketing researchers used in their studies on sustainability from 1997 to 2016. The selection and analysis of these theories and models, was based on a thorough examination of the articles’ overarching theoretical contributions. Table 4 orders the 13 theories and models based on the chronological evolution of theory, which corresponds to the proposed GREEN Framework of Sustainable Marketing (Fig. 1). The table also summarizes theory use, remarks, and extensions in marketing research on sustainability. Finally, the table lists each citation that uses that theory or model. Only theories and models used four or more times are included.

Table 5 illustrates the evolution of theory usage over the past 20 years. Theories are listed left to right in the order they most often appeared. This evolution of theory creates a chronological progression of thought from 1997 to 2016. The 13 theories and models evolved from a holistic, macro-level focus to a narrower, micro-level focus. Early on, researchers used theories and models to examine society and the environment. Years later, theories were used to explore business and institutional practices and then consumers’ attitudes and behaviors. Because researchers have focused on micro-level areas of sustainable marketing, the narrowing of theoretical and conceptual ideas has led to fragmented research. The GREEN Framework will show that while consumers are important in creating a more sustainable society (Sheth et al. 2011), they are not the sole drivers in achieving sustainable solutions. Instead, firms must also offer sustainable products and services to the marketplace that are profitable and desirable. Consumers demand products that improve their QOL and well-being (Kilbourne et al. 1997). Concurrently, firms and consumers must behave responsibly to create a sustainable marketplace. All stakeholders influence marketing decisions related to sustainability (Rivera-Camino 2007).

GREEN: a framework of sustainable marketing

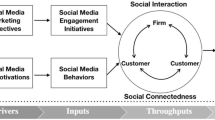

This section outlines five sustainability principles (SPs) for a framework that holistically defines and outlines a course of action for sustainable marketing. The proposed GREEN Framework of Sustainable Marketing offers a conceptual model for researchers and practitioners investigating this complex and broad domain. Sustainable marketing is based on the exchange of value between the macro level of society and the micro level of individual consumers and firms (Baker and Lesch 2013; Mittelstaedt et al. 2014) that “considers and minimizes environmental harm” (Polonsky 2011, p. 1311). Each SP is a circle within a circle. For SP2 to successfully occur, it must be built on the foundation of SP1. SP1 is a solid circle to show that sustainable marketing’s foundation is contained within a globalized marketplace of exchange. SP2 through SP5 use dotted circles to represent their interdependence—there are exchange relationships between consumers, firms, society, and the environment. SP3 and SP4 may seem redundant, as SP2 subsumes SP3 and SP4; however, SP3 and SP4 illustrate the exchange relationship between firms and consumers. Both sustainable businesses (SP3) and consumers (SP4) strive for improved QOL and well-being. All five SPs use circles to symbolize the fluid and continuous interactions and relationships among all stakeholders.

“G”: Globalized marketplace of value exchange

A globalized marketplace of value exchange is the foundation for sustainable marketing (Fig. 1). Sustainable marketing does not exist without exchange relationships that create value for consumers, firms, and society. These value exchange relationships must exist not just within one firm, city, or culture, but cross-culturally, as a globalized macro-level “megatrend” of complex issues, questions, and problems that impact all stakeholders (Mittelstaedt et al. 2014). For instance, even small mom-and-pop shops have global stakeholders, such as the producers who supply their products, consumers who shop from their online stores, and other firms that view them as competition. The (un)sustainable decisions that firms and consumers make at the micro level have macro-level implications. For example, after a 2007 tornado, the residents of the small Kansas community, Greensburg, rebuilt most of their buildings to be sustainable. When they made that decision, they did not know that their community would become a prominent case study for other communities desiring the same goal, that green companies would market new sustainable products to their residents, that the Discovery Channel would create a documentary based on their sustainability efforts, or that they would build more sustainable buildings per capita than any other community in the world (GreensburgKS.org 2018). Studies that ground SP1 explore societal goals (Kilbourne et al. 2002; Prothero and Fitchett 2000), macro-level systems-exchange relationships (Kilbourne and Pickett 2008), consumer exchanges (Robinot and Giannelloni 2010), and cultural values (Cho et al. 2013; Mittelstaedt et al. 2014), among others.

Early on, marketing researchers exploring sustainability used theories and models, such as the dominant social paradigm (DSP) and the values-beliefs-norms (VBN) theory (Table 3, Table 4, and Fig. 1). DSP and VBN theories advance marketing research by questioning sustainable business practices; consumers’ values, beliefs, and norms; and policies and laws that influence society (Cho et al. 2013). Kilbourne et al. (1997) examined sustainable consumption and consumer QOL through the DSP to understand how consumers perceive and interpret the world. The authors argued that sustainable consumption and QOL must be researched through a macro-level lens since most marketing researchers investigated sustainability through a micro-level lens of dyadic problems and exchange relationships. As years progressed, researchers started exploring sustainability through a macro-societal lens. Collectively, these studies argue that sustainability is a macro-level issue that impacts all stakeholders. The GREEN Framework posits that while firms and consumers are important, their (un)sustainable behaviors influence the macro-level marketplace and environment.

SP1 calls for a globalized marketplace, where consumers, businesses, governments, and countries compete and interact for the betterment of all stakeholders (Kilbourne and Carlson 2008). For example, a globalized marketplace should reject business monopolies or one country acting more superior than another. Humphreys (2014) found that “stakeholders held responsible for protecting the environment have also changed from government actors to company and consumer stakeholders” (p. 265). Visconti et al. (2014) argued that markets create a sustainable competitive advantage but also create value compromises in social issues, cross-cultural exchanges, and human values; hence, sustainability operates at “inter-social, inter-nation, and intergender levels” (p. 349).

There are many insights researchers have learned and still need to learn from the theories that ground SP1. Sustainable marketing researchers know that the DSP influences materialism, and materialism impacts environmental concern; in turn, environmental concern increases environmental behaviors (Polonsky et al. 2014). Moreover, the DSP contrasts with the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP), in which human activities are determined by environmental, cultural, and human factors (Roberts and Bacon 1997). This shift from the DSP to the NEP has been explored but not in much detail, and the DSP and NEP have not been explored extensively cross-culturally. Researchers know, based on VBN theory, that altruistic values have an indirect impact on environmental concern (Lee et al. 2014), and religious stewardship beliefs influence sustainable consumer behavior (Leary et al. 2016). Researching cross-cultural values between South Korea and the United States (US), Cho et al. (2013) found that vertical individualistic cultures and horizontal collectivist cultures positively influence environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Yet, researchers need to explore other variables that influence environmental behaviors, such as social norms, eco-feminism, intergenerational justice, and social and environmental activism.

SP1 calls for a foundation in value exchange. Just as Alderson (1957), Bagozzi (1975, 1978), and others grounded marketing in the theory of exchange, sustainable marketing is also rooted in value exchange. The proposed definition states that sustainable marketing is the “exchange of offerings that produce value through consumption behaviors, business practices, and the marketplace.” It is a complex exchange relationship with the planet. If the value gained does not outweigh the costs for stakeholders, sustainable marketing may not result (Lee et al. 2014). Moreover, SP1 is grounded in Hunt’s (1983) fourth fundamental explanandum of marketing: “the consequences on society of the behaviors of buyers, the behaviors of sellers, and the institutional framework directed at consummating and/or facilitating exchanges” (p. 13). Understanding how (un)sustainable global stakeholders interact, compete, and create relationships of value builds a sustainable marketing foundation.

-

SP1:

Sustainable marketing has its foundation in a globalized marketplace of value exchange.

“R”: Responsible environmental behavior for current and future generations

Responsible environmental behavior for current and future generations is dependent on SP1 (Fig. 1). SP2 closely relates to the Brundtland Commission (1987) definition of sustainability and focuses on lowering harm to the environment. The harm stakeholders inflict on the environment can produce detrimental consequences for future generations (Farley and Smith 2014); conversely, sustainable decisions made today can deliver responsible, sustainable outcomes (Hensen et al. 2016). The environmental theories and models that emerge from the literature consist of environmental concern models and green/ecological theories. They explain environmental consciousness, communication, and behavior, among others, that researchers use to investigate topics such as global warming and climate change (e.g., Baker and Lesch 2013), sustainable attitudes and behaviors of current generations (e.g., Kilbourne and Pickett 2008; Koller et al. 2011; Tu et al. 2011), strategic cross-cultural interactions and values (e.g., Borland 2009; Soyez 2012), concern for future generations (e.g., Hensen et al. 2016), and environmental messaging and claims (e.g., Maronick and Andrews 1999; Mohr et al. 1998). They question sustainability through a holistic, interactional, and diverse lens.

There are many insights researchers have learned and still need to learn from the theories and models that ground SP2. For example, Burgh-Woodman and King (2013) studied the human/nature connection, signifying that “concern for the environment is driven by an existing, historically embedded sense of human/nature connection rather than a concern for future decimation as typically thought” (p. 145). Thøgersen (2010) explored organic food consumption cross-culturally, arguing that consumption depends heavily on macro and structural factors of sustainable behaviors. Phipps and Brace-Govan (2011) studied the drought conditions of the water system of Melbourne, Australia, finding that change for the sustainable future results from changes in policy legislation, education, and marketing that is “appropriately integrated into the informal, formal, and philosophical foundations of the marketplace” (p. 203). Researchers have explored the psychological side of environmental concern and skepticism extensively. What is still underexplored is how the sociological environment also influences consumers’ environmental concern and eventual behaviors—the extent of the human/nature connection (Burgh-Woodman and King 2013). Some researchers have started exploring this area, where practice theories are used to investigate sustainable practices (e.g., Gollnhofer 2017; Hargreaves 2011; Sahakian and Wilhite 2014). However, future researchers should examine how practices and routines influence consumers’ environmental concerns and skepticism of those concerns.

SP2 is rooted in the exchange of value between humans and the environment, stakeholders’ sustainable and unsustainable actions, and current and future generations. This SP extends the theory of exchange from the buyer-seller viewpoint to a more complex relationship of exchange. It is challenging to estimate what resources future generations will need, how much they will use, or when they will need those resources. These unknown variables make the Alderson (1957) and Bagozzi (1975, 1978) exchange relationship difficult to assess, and the sustainability “attitude-behavior gap” difficult to solve (Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002). Hence, stakeholders can become skeptical and cynical about sustainable marketing. For example, Paco and Reis (2013) concluded that “the more environmentally concerned an individual is, the more skepticism he or she will be toward green claims” (p. 147). If skepticism is high, sustainable behaviors for today and for tomorrow may not result (Mohr et al. 1998).

SP2 has a foundation in Hunt’s (1983) third fundamental explanandum of marketing: “the institutional framework directed at consummating and/or facilitating exchanges” (p. 13). With sustainable marketing, the exchange of value is between stakeholders and the environment. For instance, the environment creates no waste—it is completely sustainable (Farley and Smith 2014). Therefore, the role of sustainable marketing is to promote responsible behaviors to lower harm to the environment. Hunt’s explanandum defined institutions “as sets of conditions and rules for transactions and other interactions” of goods and services (p. 14). Sustainable marketing extends this explanandum by implying that the environment is the ultimate entity of value exchange. When marketing researchers understand the opportunities and consequences of how stakeholders’ (ir)responsible environmental behaviors influence others in a globalized marketplace today, then, they can explore the impact on future generations.

-

SP2:

Sustainable marketing necessitates that society behaves in an environmentally responsible manner for current and future generations.

“E”: Equitable sustainable business practices

SP3’s focus is narrower than SP1 and SP2 and involves equitable sustainable business practices (Fig. 1). SP3 and SP4 are represented by the same size of intersecting circles in the GREEN Framework because they are interdependent in their interactional exchange relationship. Firms create value by selling products and services to customers for profit, while customers derive value from buying products and services from those firms (Hunt 1983). To be equitable, sustainable business practices must be fair and reasonable (Baker and Lesch 2013) in the eyes of both parties involved. As Seshadri (2013) concluded, sustainability is a “shared responsibility among diverse stakeholders” (p. 765). Sustainable firms can influence stakeholders (i.e., consumers, firms, governments) to be sustainable (Scandelius and Cohen 2016); concurrently, stakeholders can also demand that firms be sustainable (Varadarajan 2015). The positive and negative actions of firms impact each of the other interconnected stakeholders. This SP proposes that firms create, perform, and maintain equitable (i.e., reasonable and unbiased) sustainable business practices.

Sustainable business practices (SP3) signify more than just sustaining business at the status quo. They focus on the triple bottom line initiatives (Elkington 1994) through the firm’s sustainable strategy, innovation, and leadership (Rainey 2010). Through sustainable marketing, firms must create equitable and ethical exchanges, among not only stakeholders for today but also for future generations (Peterson and Lunde 2016). Furthermore, in the proposed definition, firms have a vital role in the “strategic creation, communication, delivery, and exchange of value of offerings that produce value…while ethically and equitably increasing quality of life (QOL) and well-being of consumers and global stakeholders…” In the past decade, many marketing researchers have used business-based and institutional-based theories (Table 4) to narrow their focus to the sustainability of firms (Table 5), using theories such as resource-based view (RBV), resource-advantage theory (RAT), macro-systems and institutional theories (MSI), and sustainable supply chain models (SSC). These theories and models question how firms can educate consumers (Polonsky 2011), employees (Baker and Sinkula 2005), and stakeholders (Cronin Jr. et al. 2011) to be sustainable. RAT and RBV posit how firms can achieve a sustainable competitive advantage.

Institutional theory states that “institutions are comprised of regulative, normative, cultural-cognitive elements that, together with associated activities and resources, proved stability and meaning to social life” (Scott 2008, p. 48). Researchers use institutional theory to explore how systems “can be challenged and repositioned to encourage greater sustainability” (Ertekin and Atik 2014, p. 1). Macromarketing theory is “the study of (a) marketing systems, (b) the impact and consequences of marketing systems on society, and (c) the impact and consequences of society on marketing systems” (Layton 2007, p. 227). Researchers use macromarketing theory to study how consumers (Schaefer and Crane 2005) and sustainable firms interact with society (Viswanathan et al. 2009), how countries’ sustainability strategies influence society (Thøgersen 2010), and how society should focus on future generations (Dolan 2002), among others. Stakeholder theory posits that stakeholders in organizations are “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives” (Freeman 1984, p. 46). Researchers use stakeholder theory to explore how firms can create value for a social and financial competitive advantage (Scandelius and Cohen 2016).

There are many insights researchers have learned and still need to learn from the theories that ground SP3. Marketing researchers understand how sustainable business practices are shared by all stakeholders and how these practices should not only be studied at the business-to-consumer level but also at the macro, business-to-society level (Meng 2015). RBV helps frame how consumers and firms use resources to frame sustainability (Varadarajan 2015), while RAT helps frame how firms can use those resources to innovate sustainable competitive advantages in the marketplace (Baker and Sinkula 2005). What is still underexplored is how researchers can use these theories and models to understand social change (Phipps and Brace-Govan 2011); how sustainable firms respond to stakeholders, societal pressures, sustainable supply chains, and international regulations and policies (Rivera-Camino 2007); how firms can use their resources to influence future generations; and how researchers can better understand the sustainable performance link between stakeholders and sustainable firms (Cronin Jr. et al. 2011).

To create sustainable value, it must be a value that stakeholders find advantageous and equitable. SP3 extends the theory of exchange (Alderson 1957; Bagozzi 1975, 1978) from the buyer-seller relationship to include value-exchange relationships among all stakeholders. SP3 is rooted in Hunt’s (1983) second fundamental explanandum: “the behaviors of sellers directed at consummating exchanges” (p. 13). Firms are discovering that to promote sustainability, they also must behave sustainably (Lunde 2013). They can then use their sustainability practices as a competitive advantage (Cronin Jr. et al. 2011). SP3 extends this fundamental explanandum by asserting that sustainable firms are not just selling products and services to consumers for profit; they are promoting sustainability to their own employees, other firms, and society. Researchers can examine how firms can equitably promote sustainable products and services through their own practices, ethics, corporate social responsibility, and policies. Moreover, SP3 lays the foundation for researchers to explore how consumers’ sustainable motivations and behaviors contribute to sustainable competitive advantage, through positive consumer-firm interaction.

-

SP3:

Sustainable marketing requires that firms engage in equitable sustainable business practices.

“E”: Ethical sustainable consumption

SP4 calls for consumers, firms, and other stakeholders to be ethically sustainable in their consumption behaviors. As shown in Fig. 1, SP3 and SP4 have a mutual but interactional relationship of value exchange. Ethical sustainable consumption refers to consumer behaviors based on moral values and doing the right thing for firms, society, and the environment (Baker and Lesch 2013). While ethical is a subjective term, the exchange between sustainable firms and sustainable consumers is based on moral values in the eyes of both parties involved. Ethically sustainable firms require sustainable consumers. If there is no one to buy a firm’s products or services, the sustainable firm will cease to exist (Xie et al. 2015). Sheth et al. (2011) argued that firms must focus on the customer, which they coined “mindful consumption.” The value exchange between ethical consumers and equitable business practices produces a sustainable society (Borland 2009).

A prominent area of research examines whether consumers’ attitudes result in sustainable behaviors, with many studies investigating this consumer “attitude-behavior gap” (Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002). Even though many firms know that sustainability is important to their competitive advantage and to society (Borland 2009), researchers recognize that until firms can close this gap between attitudes and behaviors at the consumer level, sustainability will always be a challenge. For example, Naderi and Strutton (2015) found that many consumers will only behave sustainably when they feel they will benefit from it. Research investigating sustainable purchase intentions (Hartmann and Apaoloza-Ibanez 2012), consumption behaviors (Connolly and Prothero 2003), advertising appeals (Chang et al. 2015), and ethical choices (Diamantopoulas et al. 2003) in competitive societies (Minton et al. 2012), is vital to understanding how sustainable consumers ethically behave, interact, and consume.

Marketing researchers started to use consumption-based and behavioral-based theories regularly in marketing research on sustainability after 2012, including regulatory focus theory (RFT), the theory of planned behavior (TPB), and the theory of reasoned action (TRA). They focus on how (un)sustainable consumers behave or do not behave (Seegebarth et al. 2016). For instance, Hartmann and Apaoloza-Ibanez (2012) used TRA to argue that consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions toward green energy brands are most influenced by natural brand imagery, while Kalamas et al. (2014) researched consumers’ environmental responsibility based on external, spiritual forces. They found that consumers who ascribe “environmental responsibility to powerful-others engage in pro-environmental behaviors” (p. 12). Other researchers used RFT to argue that consumers are attracted to sustainable products and services (Bullard and Manchanda 2013), advertising (Bhatnagar and McKay-Nesbitt 2016), and firms (Bullard and Manchanda 2013) when appeals that prevent unsustainable practices are used rather than appeals that promote sustainable practices. These consumption-based and behavioral-based theories examine how (un)sustainable consumers, firms, and stakeholders consume, behave, and exchange offerings of value within the natural environment.

There is still much to learn from the theories that ground SP4. Most sustainable consumption literature is framed using psychologically-based behavioral theories (e.g., TRA, TPB, RFT) to study the “attitude-behavior gap” (Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002); however, many studies show attitudes do not necessarily lead to sustainable behaviors because “consumers do not act as green as they say they do” (Perera et al. 2016, p. 2). Therefore, Burningham and Venn (2017), Reckwitz (2002), Shove (2004), and Warde (2005), among others, are calling for more studies to use practice-based, sociological theories. While a few sustainability studies (e.g., Gollnhofer 2017; Hargreaves 2011; Sahakian and Wilhite 2014) use practice theories to explore sustainable practices, researchers should investigate how sustainable behaviors become everyday practices, how and why those sustainable practices lead to sustainable routines, and how consumers maintain their sustainable routines over time.

SP4 has a foundation in the theory of exchange (Alderson 1957; Bagozzi 1975, 1978) because consumers make ethical or unethical (un)sustainable consumption choices every day. For instance, when buying light bulbs, do consumers choose the sustainable LED (light-emitting diodes) bulb or the unsustainable incandescent bulb? What price is too high for the LED bulb? Furthermore, when consuming electricity, do consumers turn the lights off or leave them on when they leave the room? These exchange relationships, among others, are prominent in sustainable consumption literature.

SP4 is rooted in Hunt’s (1983) first fundamental explanandum: “the behaviors of buyers directed at consummating exchanges,” and these behaviors of buyers are important to explain “why certain buyers enter into particular exchange relationships and others do not” (p. 13). SP4 questions why some buyers choose to consume sustainably while others choose not to consume sustainably. For unsustainable consumers, the value of consuming sustainably does not outweigh the cost, inconvenience, or reputation of being sustainable. These theories are focused on a much narrower segment of sustainable marketing; however, through these theories researchers ground sustainability in consumers’ consumption attitudes, behaviors, and practices.

-

SP4:

Sustainable marketing requires firms to promote ethical sustainable consumption and consumers to consume sustainably.

“N”: Necessary Quality of Life (QOL) and well-being

The final SP calls for sustainable marketing to engage consumers who want to increase the value of their QOL and well-being. When there is a solid foundation of responsibility for current and future generations through sustainable business practices and sustainable consumption, sustainable marketing focuses on the QOL and well-being of stakeholders of current and future generations. SP5 includes both sustainable business stakeholders (SP3) and consumers (SP4) (Fig. 1). Consumers’ QOL and well-being derive from sustainable business practices and their consumption behaviors. QOL is defined as a business strategy “designed to enhance customer well-being while preserving the well-being of the business’s other stakeholders” (Lee and Sirgy 2004, p. 44). Well-being is defined as the long-term satisfaction that preserves or enhances the QOL of consumers (Sirgy and Lee 1996). Researchers find that consumers are more inclined to behave sustainably if it also improves their QOL and well-being (Bahl et al. 2016). Decades ago, Kilbourne et al. (1997) called for more QOL and well-being research. They argued that QOL can increase through sustainable consumption practices. Years later, Sheth et al. (2011) argued that sustainability has greater success if firms focus on the mindful consumption of consumers. The QOL and well-being of consumers can increase sustainable behavior; concurrently, sustainable behavior can increase the QOL and well-being of consumers.

Dolan (2002) stated that sustainable consumption is “the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life...[and] not to jeopardize the needs of future generations” (p. 172). High QOL and well-being are not just important for consumers and stakeholders today but also for future generations (Newman et al. 2012). Improved QOL enhances stakeholders’ well-being (Kilbourne et al. 1997); avoids targeting consumers who are vulnerable, unhealthy, or unsafe (Baker et al. 2005); and provides education and ethical practices (Lee and Sirgy 2004) for firms, society, and the environment (Samli 1998). Until consumers feel they have a high QOL, they will be less inclined to focus on their sustainable consumption behaviors (Ertekin and Atik 2014).

SP5 is rooted in social-psychological theories (Table 4). These theories examine both social context and psychological phenomena (Allport 1985). Many articles supporting SP5 were published after 2012, using theories such as social norms theory, social identity theory, social cognitive theory, and construal level theory (Table 5). Researchers use these theories to explore how sustainability influences individual consumers’ norms, identities, and cognitive processes—and ultimately, their QOL. For example, Goldstein et al. (2008) examined QOL by studying consumers’ sustainable practices while staying in hotel rooms. They found that when signage is stating a social norm, such as “a majority of guests reuse their towels,” was more appealing than telling guests to be sustainable to protect the environment (p. 477). The QOL and well-being of the guests depended on the sustainable behaviors of others. Using construal level theory (CLT) (Trope and Liberman 2003), Tangari et al. (2015) found that, even though sustainability is an abstract and distal idea, proximal appeals (vs. distal appeals) were more effective for influencing consumers’ sustainable attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Many consumers do not know how behaving sustainably will affect their QOL and well-being; therefore, they may choose not to behave sustainably (Yang et al. 2015).

There are many insights researchers have learned and still need to learn from the theories that ground SP5. These theories help researchers understand how sociological and psychological factors and construal-level appeals influence sustainable behavior, norms, attitudes, and consumption practices (e.g., Chen 2016; Gleim et al. 2013; Phipps et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2015). However, most of the studies focus on the psychological side of the social-psychological spectrum; whereas, only a few explore the sociological side (e.g., Connolly and Prothero 2003; Felix and Braunsberger 2016; White and Simpson 2013). Researchers do not fully understand how social factors influence consumption and business practices, such as how social identity influences consumers’ sustainable routines, how social identity and social norms of employees influence (un)sustainable firms, and how social factors can create marketplace advantages for firms (Chabowski et al. 2011). Moreover, these theories do not fully explore how sociological factors can lead to consumers increasing their QOL and well-being.

SP5 also has a foundation in the theory of exchange (Alderson 1957; Bagozzi 1975, 1978). Consumers value their QOL and well-being (Lee and Sirgy 2004). If consumers feel that behaving sustainably is too much of an inconvenience, too high of a cost, or if their QOL and well-being are being jeopardized (Bahl et al. 2016), sustainable behavior may not result. There is a value exchange between QOL/well-being and sustainability, based on consumers’ social norms, identities, and cognition. With increased QOL and well-being (SP5), consumers will be more inclined to behave and consume sustainably (SP4), firms will improve their sustainable business practices (SP3), and stakeholders will be environmentally responsible for today and for tomorrow (SP2) because of a globalized marketplace of value exchange (SP1).

-

SP5:

Sustainable marketing engages consumers looking to increase value in their quality of life (QOL) and well-being.

Implications

The GREEN Framework produces implications for theory and practice. The proposed definition of sustainable marketing and the framework suggest that sustainability in marketing research must become more holistic. Over the years, researchers have narrowed the focus. While this created very specific research studies, it also has fragmented research studies. Until now, researchers and practitioners have not had a holistic sustainability definition specific to marketing. Researchers used theories and topic areas that focused on one or just a few stakeholders of sustainable marketing but left out other current and future stakeholders.

This review has implications for researchers as it expands the focus of sustainability in marketing, proposes a new definition of sustainable marketing, and conceptualizes the GREEN Framework. Researchers can use the framework to craft research questions, models, and theories. The proposed definition and framework create a more holistic and comprehensive view of sustainability in marketing literature. Over the years, theory usage has evolved from using theories with a macro-level focus to using theories with a micro-level focus. This has caused researchers to emphasize micro-level dyadic relationships of sustainable marketing rather than to focus on the holistic picture. This systematic review started in 1997, when Kilbourne et al. (1997) published a seminal article arguing that “micromarketing cannot examine the relationship between sustainable consumption and quality of life critically…only macromarketing can address this relationship effectively” (p. 4). Therefore, while conducting empirical research based on a holistic viewpoint can be challenging, it is necessary to return to those findings to understand and extend knowledge among complex and hierarchical value relationships in sustainable marketing.

The GREEN Framework extends Hunt’s (1983) fundamental explananda of marketing. The framework integrates the four fundamental explananda of marketing while extending those ideas to stress that sustainable marketing is a complex hierarchical relationship between consumers increasing their QOL and well-being, firms promoting ethical sustainable consumption and practicing equitable sustainable business practices, consumers and firms lowering harm to the environment, and stakeholders living and coexisting in a macro-level globalized marketplace. Analysis of the most popular theories and models used by researchers over the past 20 years shows an evolution from macro-level theories to micro-level theories. However, this micro-level focus has caused fragmentation. The GREEN Framework, based on five sustainability principles, attempts to unify research on sustainability published in marketing literature and envision sustainable marketing at the macro, holistic level.

Finally, marketing practitioners and policymakers need to create a foundation of value exchange when they create, promote, and evaluate sustainable marketing strategies and policies. They can then start to question environmental policies, advertising plans, branding strategies, responsible messaging, green products, and sustainable business practices based on the value-exchange foundation. The GREEN Framework extends the theory of exchange (Alderson 1957; Bagozzi 1975, 1978) by illustrating that exchange is dominant not only in marketing but also in sustainability. Just as the theory of exchange is the exchange relationship between consumers and firms, sustainable marketing is the complex exchange (Bagozzi 1975, 1978) between consumers, firms, and society, that lowers harm to the environment (Polonsky 2011).

Future research opportunities

The GREEN Framework and proposed definition offer many opportunities for future research that will further help clarify marketing research on sustainability and extend it into new directions. While some opportunities are presented in previous sections, this section proposes nine ideas for marketing researchers to advance sustainable marketing thought. These proposed opportunities, among many others, will broaden the literature published on sustainable marketing by encouraging studies that holistically investigate the complex exchange relationships between consumers, businesses, society, and the environment.

First, researchers could use multiple theories in one study to understand the complex nature of sustainability. They could use the TPB and macromarketing theory to understand how consumers’ (un)sustainable behaviors and norms impact, interact with, and change social practices and policies. Additionally, researchers could use the frameworks of SIT (Tajfel and Turner 1979) and practice theory (Reckwitz 2002; Shove 2004; Warde 2005) to explore how consumers’ social reference groups influence their (un)sustainable practices and routines. Others could use CLT (Trope and Liberman 2003) and a skepticism model (e.g., Maronick and Andrews 1999) to explore how geographic and psychological distance shift consumer skepticism and cynicism toward sustainability.

Second, researchers could propose a sustainable marketing theory. There is no general theory of sustainable marketing to explore the complex value-exchange relationships that comprise this domain. For instance, Bartels (1968) suggested a general theory of marketing based on seven sub-theories. Researchers have offered numerous frameworks and conceptual models (e.g., Chabowski et al. 2011; Crittenden et al. 2011), including the GREEN Framework presented in this review. Development of a general theory using the GREEN Framework as a foundational tool is a rich area for future research. Sustainable marketing extends the fundamental tenants of marketing thought (Alderson 1957; AMA 2017; Bagozzi 1975, 1978; Hunt 1983). Sustainable practices add value to the environment, such as reducing the amount of nonrenewable resources consumers use, lowering the negative actions that humans impose on ecosystems, and through consuming responsibly. In exchange, consumers and firms can use renewable resources in their consumption and business practices.

Third, as emphasized throughout this review, most marketing research published on sustainability uses psychological theories, such as TRA, TPB, and rational choice theory (Elster 1986; Homans 1961), among others, to change attitudes into sustainable behaviors. However, marketing researchers also conclude there is an “attitude-behavior gap” (Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002) since consumers do not act as sustainably as they think and say they do (Perera et al. 2016). Sociological researchers find practice theories are salient to use to understand consumers’ sustainable behaviors (Burningham and Venn 2017; Reckwitz 2002; Shove 2004; Warde 2005). For instance, research does not fully explore how consumers’ sustainable actions turn into sustainable routines, how they maintain those sustainable routines, how they become part of their daily lives, and how sustainable practices and routines influence personal identity, social identity, and cultural identity. Therefore, future research examining sustainable practices, routines, and identity are fruitful areas of observation.

Fourth, more international and cross-cultural studies are needed to understand sustainable decision-making among consumers of different countries and cultural groups. As global firms want to sell sustainable products and services to consumers and to other firms around the world, more research must empirically test cross-cultural similarities and differences in stakeholders’ (un)sustainable attitudes, practices, values, and policies. Many US-based studies are hard to generalize and extend to consumers living in other countries with unique cultural norms and behaviors. Future researchers should explore policy implications between countries and among societies, how other societies and consumers impact the environment, and how the QOL and well-being of cross-cultural consumers influence sustainable marketing strategies. Cross-cultural studies will help validate and generalize sustainable marketing for global stakeholders.

Fifth, more research must explore how consumers and firms today will affect future generations. Some market-systems research attempts to examine this phenomenon (e.g., Doganova and Karnoe 2015; Mittelstaedt et al. 2014; Phipps and Brace-Govan 2011), but this area is still highly underexplored. One way to explore this area of research is to examine past case studies. If researchers can identify and understand how the environmental research of the 1970s and 1980s, for example, influenced policies, societies, firms, and consumers today, then they can apply their insights to predict how (un)sustainable actions today might affect future generations. Researchers could take past studies, such as the study that examined sustainable social change that resulted from a water shortage in Melbourne, Australia (Phipps and Brace-Govan 2011), or the study that explored environmental product development performance within British manufacturers (Pujari et al. 2004), to examine how social change and product performance is affecting future consumers.

Sixth, researchers should investigate stakeholders’ core values (i.e., reliability, optimism, commitment, loyalty, consistency, compassion, and responsiveness) (Visconti et al. 2014) relating to sustainable business practices and consumption behaviors and how those values influence their QOL (Lee and Sirgy 2004) and well-being (Sirgy and Lee 1996). By assessing how values impact the sustainability of consumers and firms (e.g., Crittenden et al. 2011), researchers and practitioners can create more solutions-based strategies, understand what triggers sustainable responsiveness in consumers (e.g., Phipps and Brace-Govan 2011), better analyze consumers’ price sensitivity to sustainable products and services (e.g., Thøgersen 2010; Hunt 2011), and devise innovative and reliable sustainable strategies (e.g., Gabler et al. 2015; Varadarajan 2015), among others.

Seventh, using SP5 as a theoretical starting point, researchers can examine how sustainability impacts consumer decision-making processes. How do consumers react when their QOL stagnates (e.g., due to their own choices), when the marketplace is disrupted (e.g., during and/or after natural disasters and economic recessions/depressions, and after implementing governmental policies), or when institutions fail to focus on responsible environmental behavior (e.g., either deliberately or through greenwashing)? Researchers could explore how the QOL and well-being of consumers influence the (un)sustainable behaviors of all stakeholders. Researchers also should explore the spiritual antecedents of environmental behavior. Literature in the past 20 years has scantly studied how consumers’ altruistic values impact environmental concern (e.g., Lee et al. 2014), how religious beliefs affect the sustainable behavior of consumers (e.g., Felix and Braunsberger 2016; Leary et al. 2016), and how environmental responsibility derives from external forces beyond their direct control (e.g., Kalamas et al. 2014). Future researchers could study how sustainable behavior affects QOL and well-being by exploring how consumers’ sustainable actions can help them find meaning in life, find inner peace, and rediscover their personal and social identities.

Eighth, more research should examine sustainable marketing measurement. While a few of the 228 articles identified this as a subject of future research (e.g., Karna et al. 2003; Mitchell et al. 2010; Seshadri 2013), no studies have described how effectively to measure, operationalize, and evaluate sustainable marketing practices. Currently, it is difficult to measure if a firm’s sustainable marketing strategies are effective, to assess the sustainability of one firm compared to another, or to evaluate a firm’s (un)sustainable consumers and stakeholders, among others. Therefore, future researchers can develop frameworks and models that other researchers, practitioners, and policymakers can use to evaluate the efficiency, effectiveness, and quality of their sustainable marketing plans, policies, and strategies.

Finally, the methods in this review could be expanded. Building on this review, future researchers could increase the number of marketing journals they examine and/or include journals from other disciplines. Future review studies could include more keywords than were used in this review or change the methodology from a systematic review to a content analysis, a citation analysis, or a meta-analysis. While these suggestions do not decrease the value of this review and its findings, they would help confirm the findings of the GREEN Framework, the sustainable marketing definition, and the proposed opportunities for future research.

Conclusion

This systematic review examined 228 articles on sustainability published in the top 25 marketing journals over the past 20 years (1997–2016). Through a conceptual integration process (MacInnis 2011), it highlighted the fragmented past of marketing research investigating sustainability and illustrated how theory has evolved. This review offered a new, holistic definition of “sustainable marketing.” Through the foundations of marketing thought (Alderson 1957; Bagozzi 1975, 1978; Hunt 1983) and the 13 most used theories and models used in marketing research on sustainability, this review conceptually and theoretically clarified and extended research through five sustainability principles that formed the GREEN Framework of Sustainable Marketing. Finally, the GREEN Framework created many opportunities for future research. By changing the research focus to a more holistic, unified, and macro-level approach, which includes all stakeholders, this review provided substantive insights that will benefit researchers, practitioners, and policymakers who are researching questions, practices, and policies at the nexus of marketing and sustainability.

References

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Alderson, W. (1957). Chapter 7: Matching and sorting: The logic of exchange. In Marketing behavior and executive action: A functionalist approach to marketing theory (pp. 195–228). Homewood: Richard D. Irwin, Inc..

Alderson, W. (1965). Dynamic marketing behavior. Homewood: Irwin.

Allport, G. W. (1985). The historical background of social psychology. In G. Lindzey & E. Eronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 5–20). New York: McGraw Hill.

AMA. (2017). American Marketing Association AMA website. Retrieved March 20, 2017 from http://www.ama.org.

Arquitt, S. P., & Cornwell, T. B. (2007). Micro-macro linking using system dynamics modeling: An examination of eco-labeling for farmed shrimp. Journal of Macromarketing, 37(3), 243–255.

Bagozzi, R. (1974). Marketing as an organized behavioral system of exchange. Journal of Marketing, 38(October), 77–81.

Bagozzi, R. (1975). Marketing as exchange. Journal of Marketing, 39(4), 32–39.

Bagozzi, R. (1978). Marketing as exchange: A theory of transactions in the marketplace. American Behavioral Scientist, 21(Mar/Apr), 535–556.

Bagozzi, R. (1979). Toward a formal theory of marketing exchanges. In O. C. Ferrell, S. Brown, & C. Lamb (Eds.), Conceptual and theoretical developments in marketing (pp. 431–447). American Marketing Association: Chicago.

Bahl, S., Milne, G. R., Ross, S. M., Mick, D. G., Grier, S. A., Chugani, S. K., Chan, S., Gould, S. J., Cho, Y.-N., Dorsey, J. D., Schindler, R. M., Murdock, M. R., & Mariani, S. B. (2016). Mindfulness: The transformative potential for consumer, societal, and environmental well-being. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 35(2), 198–210.

Baker, B. L., & Lesch, W. C. (2013). Equity and ethical environmental influences on regulated business-to-consumer exchange. Journal of Macromarketing, 33(4), 322–341.

Baker, W. E., & Sinkula, J. M. (2005). Environmental marketing strategy and firm performance: Effects on new product performance and market share. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(4), 461–475.

Baker, S. M., Gentry, J. W., & Rittenburg, T. L. (2005). Building understanding of the domain of consumer vulnerability. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(special issue), 128–139.

Bartels, R. (1968). The general theory of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 32, 29–33.

Bhatnagar, N., & McKay-Nesbitt, J. (2016). Pro-environment advertising messages: The role of regulatory focus. International Journal of Advertising, 35(1), 4–22.

Borland, H. (2009). Conceptualizing global strategic sustainability and corporate transformational change. International Marketing Review, 26(4/5), 554–572.

Bourlakis, M., Maglaras, G., Gallear, D., & Fotopoulos, C. (2014). Examining sustainability performance in the supply chain: The case of the Greek dairy sector. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(1), 56–66.

Brindley, C., & Oxborrow, L. (2014). Aligning the sustainable supply chain to green marketing needs: A case study. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(1), 45–55.

Brundtland Commission. (1987). Our common future: World commission on economic development. Brundtland Report. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bullard, O., & Manchanda, R. V. (2013). Do sustainable products make us prevention focused? Marketing Letters, 24(2), 177–189.

Burgh-Woodman, H., & King, D. (2013). Sustainability and the human/nature connection: A critical discourse analysis of being "symbolically" sustainable. Consumption Markets & Culture, 16(2), 145–168.

Burningham, K., & Venn, S. (2017). Are lifecourse transitions opportunities for moving to more sustainable consumption? Journal of Consumer Culture (forthcoming).

Chabowski, B. R., Mena, J. A., & Gonzalez-Padron, T. L. (2011). The structure of sustainability research in marketing: 1958-2008: A basis for future research opportunities. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 55–70.

Chan, R. Y. K., He, H., Chan, H. K., & Wang, W. Y. C. (2015). Environmental orientation & corporate performance: The mediation mechanism of green supply chain management and moderating effect of competitive intensity. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(4), 621–630.

Chang, H., Zhang, L., & Xie, G.-X. (2015). Message framing in green advertising: The effect of construal level and consumer environmental concern. International Journal of Advertising, 34(1), 158–176.

Chen, M.-F. (2016). Impact of fear appeals on pro-environmental behavior and crucial determinants. International Journal of Advertising, 35(1), 74–92.

Cho, Y.-N., Thyroff, A., Rapert, M. I., Park, S. Y., & Lee, H.-J. (2013). To be or not to be green: Exploring individualism and collectivism as antecedents of environmental behavior. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1052–1059.

Cleveland, M., Kalamas, M., & Laroche, M. (2012). "It's not easy being green": Exploring green creeds, green deeds, and internal environmental locus of control. Psychology & Marketing, 29(5), 293–305.

Collins, C. M., Steg, L., & Koning, M. A. S. (2007). Customers' values, beliefs on sustainable corporate performance, and buying behavior. Psychology & Marketing, 24(6), 555–577.

Connelly, B., Ketchen Jr., D. J., & Slater, S. F. (2011). Toward a "theoretical toolbox" for sustainability research in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 86–100.

Connolly, J., & Prothero, A. (2003). Sustainable consumption: Consumption, consumers, and the commodity discourse. Consumption Markets & Culture, 6(4), 275–291.