Abstract

This paper provides the first evidence on the dynamics of immigrant students’ achievement following their migration to Spain. Using the data from 2003, 2006 and 2009 wave of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), we show that immigrant students tend to perform significantly worse than native students, but that their performance improves with time spent in Spain. Among immigrants, Latin Americans enjoy an initial linguistic advantage, which, however, does not help them to catch up faster. The rate of improvement is such that students who stay almost all their lives in Spain still perform worse than natives in all domains analyzed by PISA. To better understand this achievement gap, we decompose it into parts attributable to school quality and to family characteristics. We observe that most of the gap is explained by individual and family characteristics and that less than 15 % of it can be attributed to differential school attendance. Overall, the evidence suggests that policies that do not target the learning environment in disadvantaged families are likely to have a limited impact on the native-immigrant achievement gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

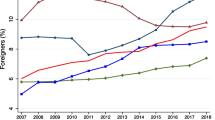

Over the last decade Spain has experienced an unprecedented increase in immigrant population, receiving almost half of the EU’s total immigration flows. The percentage of immigrant students in the Spanish educational system has also constantly risen since the beginning of 2000s and is now over 15 % in some autonomous communities (Figs. 1, 2), with especially high proportions of immigrant students in primary and lower secondary education (Table 1). An important aspect of these changes is that students of immigrant origin in Spain have a relatively lower achievement than native students. According to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), the average gap between immigrant and native students is about 0.7 of the standard deviation of scores in Spain and is rising over time.Footnote 1 This paper provides the first evidence of the dynamics of immigrant students’ achievements following their migration to Spain. To better understand the source of the immigrant-native achievement gap, we also decompose it into parts attributable to differential school attendance and to family characteristics.

The rising proportion of immigrant students in Spain has led to a growing amount of literature studying the impact of immigration on the education system. Anghel and Cabrales (2010) analyze the performance of 6th grade students in Madrid and document the substantial achievement gap between immigrant and native students, mostly driven by the low performance of students from Latin America. Using the same data, Silaghi (2011) shows that there is a negative correlation between the proportion of immigrant students in school and the performance of native peers. Ciccone and Garcia-Fontes (2009) assess the sources of the underperformance of Spain in 2006 PISA data. They show that the low performance of Spanish students in PISA, relative to students in better performing countries, can only partially be attributed to the lower educational level and the immigrant background of their parents.

The existing literature, however, does not analyze whether the achievement gap between immigrants and natives shrinks over time that immigrants live in Spain. The authors also do not explicitly quantify the school contribution to the immigrant-native achievement gap. Both pieces of information are nevertheless important for efficient policy design. On the one hand, if the gap closes quickly during the time that immigrants spend in the destination country, one might hope that children from immigrant families would not need any substantial additional policy intervention in order to catch up with native students. In the case of Spain, an argument in favor of this possibility is that a large proportion of immigrants (about 50 %) come from Latin America (Fig. 3), and that their local language proficiency might help them to be especially fast in catching up with native students. On the other hand, the problem could be more serious; the achievement gap between immigrant and native students might well be affected by the social segregation of students across schools with different resources and students’ background (Schneeweis 2006; Entorf and Minoiu 2005). If this segregation exists and it inhibits immigrants’ ability to catch up, policy intervention might be desirable. In this case, the policy would depend on the exact source of the problem. If it is associated with unfavorable peer effects, students from disadvantaged backgrounds or who have language deficiencies might be encouraged to attend schools with higher proportions of better-performing peers.Footnote 2 If immigrant students are disproportionately enrolled in schools with worse resources or educational practices, these disadvantages could be addressed.Footnote 3

Given this motivation, we contribute to the literature in the following way: using the data from the three waves of PISA survey, we first assess the significance of the achievement gap between immigrant and native students in Spain and analyze the speed of the catch-up process over time that immigrants spend in Spain. Second, we analyze which part of the achievement gap can be attributed to the differential school attendance by native and immigrant students. Finally, we explore the school-level characteristics that are likely to inhibit the catch-up process of immigrant students. Specifically, we are interested in understanding whether immigrant students are disadvantaged in terms of resources available at their schools and whether they are likely to be subject to worse peer effects.

We find that, generally, immigrant students improve their performance the longer they stay in Spain. This result is robust to controlling for observable individual-level characteristics, including, most importantly, immigration cohort fixed effects. We do not find any evidence supporting the hypothesis that native language proficiency helps immigrant students from Latin America to catch up faster. The speed of the catch-up process is such that students who have spent almost all their lives in Spain still perform worse than natives in all domains analyzed by PISA. This suggests that children of immigrants now arriving in Spain will probably only partially close the performance gap with native students by the end of their compulsory education.

No more than 15 % of the gap between immigrants and natives could be attributed to social segregation across schools. In contrast, over half of this performance gap may be attributed to only a few observed individual and family characteristics.

The low effect of school characteristics on the native-immigrant achievement gap suggests that policies addressing immigrant students’ performance should perhaps focus on directly assisting disadvantaged families rather than encouraging immigrant students to attend certain type of schools or disproportionately increasing resources provided to schools with a higher proportion of immigrants.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the recent immigration history in Spain and summarizes the main policy concerns related to the integration of immigrant children in Spanish schools. Section 3 describes the data sources for our empirical analysis and Sect. 4 presents the results of the empirical analysis. Finally, Sect. 5 provides a conclusion to our findings.

2 Immigration and education in Spain: stylized facts

Substantial demographic changes, rapid immigration flows and increasing segregation of immigrant students in schools are factors that have recently characterized the Spanish educational system and which might affect it during the next decade. In this section we describe these features of the Spanish educational system in more detail.

2.1 Demography and immigration

As a result of one of the lowest fertility rates in the world, the number of students in Spain declined by near 1.5 million in the last decade of the 20th century. By 2007, however, the educational system had recovered more than 400,000 students, due to a gradual increase in fertility rates and a massive inflow of immigrants (see Fig. 1). Therefore over time, the educational panorama is changing in a fast and an intense way.

The effects of the demographic trend and the immigration flow can be clearly observed by comparing the evolution of the number of native and immigrant students across the levels of education (see Table 1). Since 1998–1999, there has been a dramatic decrease in the number of students in upper secondary school with the overall number of students dropping by 35.7 %. In primary schools and lower secondary education, the current number of students is practically the same as it was a decade ago. At the same time, the number of students in pre-primary education has increased by around 45 %. The number of immigrant students has also multiplied by 8–9 times in pre-primary, primary and secondary levels of education.Footnote 4

The geographical distribution of immigrant students has not been homogeneous across the regions (autonomous communities) of Spain (Fig. 2). La Rioja, Madrid, Catalonia and Balearic Islands have had the largest increase in the percentage of immigrant students, which now stands above 15 % in the secondary education institutions of these autonomous communities. At the same time, some regions still have less than 7 % of immigrant students at this educational level (Asturias, Galicia, Extremadura and Andalusia).

Since the 1990s, there have been substantial changes in the composition of immigrant groups to arrive in Spain. In the schooling system there has been a rapid increase in the share of immigrants coming from Latin America, although this has stabilized in the last few years (see Fig. 3). After the enlargement of the European Union, the share of European immigrants from new EU member countries has also increased quite substantially. At the same time, there has been a decrease in the share of immigrants from EU-15 countries.

The average parental educational level of immigrant students has declined since the end of the 90’s (Table 3): while in 1999, 33–34 % of immigrant students in primary and secondary education had at least one parent with a university diploma, by 2008, this figure had decreased to 20–22 %. In contrast, however, the average educational level of native students’ parents has grown quickly: while in 1999, 20–25 % of native students had at least one parent with a university diploma, this figure had grown to around 40–50 % in 2008. If parental education determines student educational outcomes, the achievement gap between immigrant and native students is likely to widen in the future.

2.2 Educational system

Although a substantial decentralization of the education system has taken place over the last decade and numerous educational laws have been approved, the basic features of the Spanish educational model have not varied during the last 25 years. Education in Spain is largely public and free and is compulsory until the age of 16.Footnote 5 Private schools that receive public funding (or semi-private schools, in Spanish, colegios concertados) are, by and large, forced to follow the same guidelines as public schools and there are only a few private schools that do not receive any public funds at all.

One of these guidelines requires that students be selected for admission mainly on the basis of residential criteria. As such, the differential distribution of native and immigrant students across different types of schools should be then due to different housing locations. Nevertheless, some additional factors might cause segregation of immigrants across public and semi-private school. For instance, in most regions pre-primary schooling used to be paid. Students whose families have paid for admittance at this level are given priority when applying for primary level at the same school. Therefore the socio-economic background of students in semi-private schools is likely to be superior to that of students in public schools.

During the last decade the proportion of native students in public schools has decreased substantially in pre-primary education and slightly in primary and secondary levels (see Table 4). The segregation of immigrants into public schools has occurred at a different pace across the country and has generally been related to the size of immigration flows. Given the high segregation rate in pre-primary education, one might expect that during the next few years the segregation of immigrants across public and private and semi-private schools will rise at all levels of the educational system.

The main difference between private and public (as well as semi-private) schools is in the availability of resources, in student selection and in governance. Generally, private schools in Spain have an advantage in the quality of educational resources such as computers, audio-visual equipment, etc. Still, contrary to most of the OECD countries, a peculiar characteristic of Spanish private schools is that the ratios of students to teaching staff are higher than in the public sector. According to OECD (2008) “Education at a Glance”, at the lower secondary level in Spain there are 16 students per teacher in private institutions compared with only 11 in public institutions. These differences only partially reflect the differences in class size, which are 24 and 26 students per class in the public and in the private sector respectively. Most differences are driven by the lower teaching loads in public schools, a result of the strong union protection received by teachers in the public sector.

2.3 Educational outcomes

The OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) recently revealed that Spanish 15-year-old students perform well below the OECD average in all analyzed domains. In the areas of mathematics and reading, the average Spanish student obtains around 20 % of a standard deviation lower scores than that of students in OECD countries, and in science this gap is around 10–15 % of a standard deviation. While the situation does not seem to improve much over time, the outcomes vary substantially across the Spanish regions, with Northern regions generally performing better than the Southern ones. The report on PISA results in Spain by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Research shows that some Spanish regions (Castilla y León, La Rioja) perform at the level of Korea, Germany and the UK, whereas others (Andalucía) perform only at the level of Greece (Ministerio de educación y ciencia (2006)).

International evidence suggests that schools may overall account for a substantial part of the performance differences across students. According to the 2009 PISA data, 41.7 % of the variation in students’ performance in OECD countries occurs across schools. Spain scores relatively low on this indicator: only 20 % of the variation in the performance of students in Spain is across schools (Ministerio de educación y ciencia (2010)). Spain also seems to have a relatively high equality of opportunity in education in the sense that students’ outcomes depend less on parents’ educational background than in other European countries (Calo-Blanco and Villar Notario (2010)).

According to 2006 PISA data, the average performance of immigrant students residing in Spain is particularly low, being close to the average performance in Mexico and Turkey.Footnote 6 On average, the gap between immigrant and native students is about a half of the standard deviation of scores in OECD and in some regions it is above 80 % of the standard deviation. The gap increases over time in all domains (Fig. 4).

The relatively worse performance of immigrants in secondary education is consistent with their consequent lower attendance rates in post-secondary education (Fig. 5). Moreover, the difference in educational attendance between natives and immigrants increases with age. In order to prevent potential social conflicts in the future, one would want to understand the factors affecting the relative underperformance of students with an immigrant background.

3 Data

Our analysis is based on data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Initiated in 2000 in all member countries of the OECD (and several non-OECD countries), the Programme carries out a common international test every three years in order to assess the achievement of 15-year-olds in reading, mathematics and sciences. The PISA target population is made up of all students who are between 15 years and 3 months old and 16 years and 2 months old at the time of the assessment, independently of the institution they attend and the grade. The scores are scaled to have a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100 at OECD level.

In our analysis we use the 2003, 2006 and 2009 waves of PISA assessment in Spain. In total, 56,282 students in 3,065 schools (around 30 students per school) were assessed in these three waves. The number of assessed students in each school does not vary much: about two percent of schools had less than ten students assessed and only about one percent of schools had more than 40 students assessed. The assessed students in a given school do not necessarily study in the same class or grade, and the exact class they attend is not observable. The school identifiers are unique to each PISA wave, and it is impossible to detect whether any of the schools were assessed in several waves.

Apart from the assessment of students’ cognitive abilities, PISA has collected survey information on students’ background characteristics, such as parental education and occupation, home possessions, the country of birth and the time of immigration. It also contains survey data on school characteristics, such as student-teacher ratio, average class size, quality of educational resources, etc. This survey information is missing for some students and schools and we generally drop observations containing missing values for our main variables. However, in some cases, when the incidence of missing values can be correlated with the immigrant status (as for parental education and occupation), we keep observations with missing values and define corresponding categories. Altogether, our final sample consists of 48,429 observations.

Individual and family characteristics All respondents to PISA surveys were asked to report whether they and each of their parents were born in Spain or abroad. We use this information to characterize student immigration status. Specifically, we define four broad categories of students according to their origin: foreign-born students whose parents are both born abroad (FB-FP); students born in Spain whose parents are both born abroad (SB-FP); foreign-born students with at least one parent born in Spain (FB-SP); and students born in Spain with at least one parent born in Spain (SB-SP).

Most students in our sample—92.9 %—were born in Spain and have at least one parent born in Spain (SB-SP). Still, around 5 % of students in the sample are FB-FP. Note that this statistics refers to the pooled data across years. At the same time, the proportion of FB-FP students has increased from 1.8 % in 2003 to 7 % in 2009. The proportion of Spanish-born students with both parents born abroad (SB-FP) is 0.8 % in our sample, a figure which has also increased over time: from 0.4 % in 2003 to 1.2 % in 2009. The proportion of foreign-born students with at least one parent born in Spain (FB-SP) is about 1.5 % and this has not varied over the period of time under consideration.

PISA surveys also collect information on students’ individual and family characteristics. In this paper we use students’ gender and age, their parents’ education and occupation, the number of books at home as well as the availability of a computer and a study place at home.Footnote 7 The descriptive statistics for the above individual characteristics are presented in Table 5. The data reveals that immigrant students suffer a substantial disadvantage with respect to natives in terms of their family background. The occupational status of immigrant parents is lower, with only 27 % of immigrant students having parents in high skilled white-collar occupations, compared to 40 % of native students. While only 79 % of immigrant students have a computer at home, this number increases to 88 % for native students. Most parents of immigrant students have about 11-s-25 books at home, whereas this number is about 26–100 for a median native student. There are no substantial differences in the educational level of parents across native and immigrant students. This might suggest that the pool of immigrants in our sample is quite heterogeneous. In fact, as it was shown in Table 3, immigrant students in 1999 had relatively more educated parents than natives. Nowadays the opposite is the case. In the period analyzed in this paper there was a turn around in the composition of the immigrant population: our sample shows that while in 2003 the proportion of students with tertiary-educated fathers was higher among immigrants, the opposite was true in 2009.

For students who are born abroad, the data include the year of their arrival in Spain and the language that is typically spoken at home. The average immigrant student examined in the data moved to Spain at the age of 10 and about 70 % of immigrant students in the sample speak Spanish at home (a fact that most likely signals their Latin American origin). Finally, the majority of native students (67 %) reported attending the 10th grade (according to OECD standardized educational categories), while the majority of immigrant students attended only the 9th grade (53 %).Footnote 8

School-level characteristics The schools in which PISA assessments were held were asked to provide information on a number of school-level characteristics, such as ownership, location, school size, the average class size.Footnote 9 Schools were also asked to characterize the educational resources available for students, such as instructional materials, computers, software, calculators, library materials, audio-visual resources and science laboratory equipment, etc. This information was summarized by the OECD in an index reflecting the quality of educational resources. In addition to the above characteristics, we create other school-level variables applying sample stratification weights to the variables of interest and averaging the weighted variables for students from a given school. Using this procedure, we calculate the share of immigrant students among 15-years old students in the school and the average parental education of these students.

In accordance with the official statistics, we observe that immigrant students in our sample are more likely to attend public schools than native students do (Table 5): 80 % of FB-FP students study in public schools vs. 63 % of SB-SP students.Footnote 10 Immigrant students are underrepresented both in private and in semi-private schools.

There are some important differences between private and public schools (Table 6). In line with OECD reports, we observe that private schools have higher student-teacher ratios than public schools. Average class size is also higher in private schools than in the public sector. Given that the curricula is generally standard for all schools, it is possible to calculate an approximate teaching load in terms of the number of classes per teacher by dividing student-teacher ratio by the average class size. We normalize this measure across schools in our sample, and observe that teaching loads tend to be substantially higher in private schools. Nevertheless, private schools report significantly higher quality of educational resources. Parents of students in private schools also appear to have spent more years in education than parents of students in public schools. Among other characteristics, we also observe that private schools are more likely to be located in the cities and that they are larger in terms of the total number of students. There are no significant differences across public and private schools in streaming of students by ability.

Given the segregation of immigrant and native students across private and public schools, the differences between the two types of schools are generally reflected in the educational input received by immigrant and native students (Table 5).

4 Empirical analysis

We begin our empirical analysis by testing the significance of the performance gap between immigrant and native students. We then analyze whether immigrants tend to improve their performance over the time they live in Spain and whether those immigrants who come from Latin America tend to catch up faster.Footnote 11 Next, we analyze which part of the gap could be attributed to the compositional differences between the sample of immigrants and the sample of natives in terms of their family background and the characteristics of schools that they attend. Finally, we analyze the role of specific educational resources and the importance of peer effects for the relative achievement of immigrant students.

4.1 The size of the performance gap and the catching-up

Table 7 summarizes the averages of PISA scores in the areas of mathematics, reading and science by origin of students. It may be observed that FB-FP students perform significantly worse than native students. In mathematics FB-FP students obtain around 57 points less than native students, which is equal to more than a half of the standard deviation of scores in the OECD. The achievement gap between immigrants and natives is equal to around 0.7 of the standard deviation of scores in Spain. This performance gap is significant at the level of one percent. Similar gaps are observed in reading and sciences—52 points and 57 points respectively.

Spanish-born students with foreign-born parents (SB-FP) also perform significantly worse than native students. The gap between the average performance of this group, however, and natives is relatively smaller than that of FB-FP: between 0.3 and 0.4 of the standard deviation of scores in Spain. The scores in all disciplines are significantly lower for FB-FP students than for SB-FP. The fact that these differences exist is consistent with the idea that, for an immigrant, more time spent in Spain might be associated with higher academic achievement.

The scores of SB-SP and FB-SP students are also significantly different, but the magnitude of this difference is smaller than in the case of native students and students with foreign-born parents.

We proceed by analyzing whether the achievement gap between immigrant (FB-FP) and native (SB-SP) students closes during time that immigrant students live in Spain. Specifically, we estimate the following equation:

where \(S_{i}^{d}\) stands for the score achieved by immigrant student \(i\) in domain \(d\) and \(YearsInSpain_{i}\) is the number of years elapsed since this student’s family immigrated to Spain. In order to attribute the time effect to the process of catching up we would need to compare immigrant students with similar characteristics, but who have spent different periods of time in Spain. Therefore we first control for some observed individual and family background characteristics \(\mathbf X _\mathbf i \) that are predetermined to the time of migration. This includes gender, age, and parental education. We don’t control for post-immigration characteristics, such as parental occupation and family possessions, since they are likely to be correlated with the natural integration process. It is possible that immigrants do not bring all their belongings from their countries of origin but buy new goods after moving to Spain, accumulating more over time. Parental occupation is also likely to improve the longer the family stays in Spain.

Still, apart from their educational background, the cohorts of immigrants are likely to differ in many other respects (see Sect. 2 for more details). Given the repeated cross-sectional nature of the data, we are able to control for immigration cohort fixed effect, \(\mathbf D _\mathbf c \). Consequently, we exploit the variation across students who arrived in Spain in the same year, but at a different age, and thus were assessed by PISA in different waves. We also allow for time fixed effects \(\mathbf D _\mathbf t \).

Estimation results for Eq. (1) are shown in Table 8. On average, an additional year spent by an immigrant student in Spain is associated with an additional 2.9 points in reading, 4.5 points in math and 5.5 points in science (column 1), though the estimated coefficients are relatively noisy. The effect is statistically significant only in the sciences. The point estimates suggest that even for immigrant children who have spent almost their entire life in Spain, the catch-up process is not sufficient to close the gap with native students by the end of compulsory education, especially in mathematics and reading.Footnote 12

We then assess the speed of the catch-up process separately for immigrants with different linguistic background, namely, for immigrants whose native language is other than Spanish and for immigrants whose native language is Spanish (columns 2–3). The first thing to notice is that on average the two groups of immigrant students have statistically similar scores in mathematics and sciences, but immigrants from Latin America have significantly better scores in reading. Nevertheless, even in reading, there is still a very large gap between students who are Spanish-speaking immigrants and those who are natives. We find that Spanish-speaking immigrants do not catch up faster with natives relative to the rest of immigrant students. In none of the domains, does the time since immigration is significantly correlated with the performance of students from Latin America. Instead, immigrant students from other countries exhibit a significant catch-up process in all domains. This striking result suggests that the knowledge of local language per se does not guarantee better educational dynamics for immigrant students from Latin America. Although they tend to be better prepared than the rest of immigrant students upon arrival, students from Latin America are unlike other students in that they do not improve their performance over time and do not eventually catch up with native students. This pattern cannot be attributed to the differences in observed family characteristics.Footnote 13

Overall, our results suggest that with the current rate of improvement for immigrant students, immigrant children recently arrived in Spain would not be able to completely close the achievement gap with natives by the age of 16. The persistence of the achievement gap is especially important for children from Latin America.

As column 4 of Table 8 suggests, the catch-up rate of foreign-born students with Spanish parents (FB-SP) is sufficient for children entering the education system to completely close the achievement gap with native students by the age of 16. Generally, their speed of convergence is not statistically different from that of other immigrant students, but, in contrast to the rest of immigrant students, they start from a higher initial level of achievement.

In the following, we investigate the reasons for the relatively low performance of immigrant students. The achievement gap might persist if immigrants have access to schools with poorer resources and weaker teachers. We quantify the relative contribution of family and school characteristics in explaining the achievement gap.

4.2 Family and school as determinants of educational achievement

We model the educational production functions of native and immigrant students in the following way:

where \(\mathbf{X }_{N}\) and \(\mathbf{X }_{I}\) stand for individual and family characteristics of respectively native and immigrant students, and \(\mathbf{Y }_{N}\) and \(\mathbf{Y }_{I}\) are the vectors of school characteristics attended by respectively native and immigrant students. We assume separability of the production factors, and allow the factors to have a different effect on achievement for immigrant and native students.

In order to describe the contribution of observable individual and school characteristics to the total achievement gap between immigrant and native students, we perform Oaxaca–Blinder decompositions. This procedure splits the overall performance gap into two parts: the one that is explained by the composition of the two subsamples in terms of endowments of observable characteristics (either \(\mathbf X_i \) and \(\mathbf Y_i \)), and the part that is explained by the group differences in returns to endowments (\(\beta ^j_N\) vs. \(\beta ^j_I\)):

In Eq. (4), \(\bar{\mathbf{X }}_{N}\) and \(\bar{\mathbf{X }}_{I}\) stand for average individual and family characteristics of native and immigrant students, and \(\bar{\mathbf{Y }}_{N}\) and \(\bar{\mathbf{Y }}_{I}\) are average school characteristics attended by native and immigrant students, respectively. \(\hat{\beta }^X_{N}\) and \(\hat{\beta }^X_{I}\) are the coefficients of the estimated importance of different family inputs for the achievement of respectively native and immigrant students, whereas \(\hat{\beta }^Y_{N}\) and \(\hat{\beta }^Y_{I}\) are the importance of school characteristics for their achievement.

Given the observational nature of PISA data, it is impossible to exactly identify the endowment effects of school and family characteristics, since there may be sorting of students with different (observed or not) family characteristics across schools. Still, if we believe that students with a poorer socio-economic background generally tend to sort into schools with poorer characteristics, we might estimate the upper bound of schools’ contribution to the achievement gap. We can do so by calculating the proportion of the achievement gap that is explained by school fixed effects without conditioning on family characteristics \(\mathbf{X }\). If we are interested in identifying the upper bound of the endowment effect of some specific observable school characteristics, we can calculate decomposition of Eq. (4) only based on the school characteristics of interest.

Based on the same assumption, we can identify the upper bound of the effect of observable family characteristics on the achievement gap by calculating decomposition of Eq. (4), based only on the family characteristics \(\mathbf{X }\) and without conditioning on school characteristics \(\mathbf{Y }\). On the contrary, the lower bound of the effect of observable family characteristics could be obtained by including school fixed effects in \(\mathbf{Y }\).

How credible is it to assume that there is a sorting of immigrant students into worse schools? As Table 5 shows, immigrant students are relatively more likely to study in public schools that generally have poorer educational resources than private schools. However, in Spain these schools also have fewer students per class and teachers with smaller teaching loads. So potentially, school fixed effects might underestimate the upper bound of the school contribution to the achievement gap. The size of this attenuation would depend on the importance of class size and teaching load in the education production function.

4.2.1 School contribution to the achievement gap

Table 9 reports different specifications of Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions. Panel (a) presents decomposition results for the average gap between native and immigrant student, panel (b) analyzes the gap between native students and immigrant students from Latin America, and panel (c) considers the gap between native students and immigrant students from other countries. Every block corresponds to a separate decomposition exercise. The corresponding estimates of the education production functions (Eq. 2) and Eq. (3) are reported in Tables 11, 12, 13, 14 in the Appendix.

We observe that students’ between-school segregation as measured by school fixed effects explains around six points of the immigrant-native achievement gap in mathematics, which is around 11 % of the total gap (panel a). Between-school variation of the achievement gap is smaller in reading and science, around four points or 7–8 % of the total gap. It is even less successful in explaining the underperformance of immigrant students from Latin America (panels b and c).

In the following specification of panel (a) we show that the school effect can be mainly attributed to the segregation of immigrant and native students across public and private schools. Estimations of the education production functions suggest that both immigrant and native students do better in private schools and that the advantage of private schools cannot be explained by observable school characteristics, such as class size, teaching load, the quality of educational resources and others (columns 1–2 of Tables 11, 12, 13).

There is no significant correlation between the class size and students’ performance, whereas higher teaching loads tend to be negatively correlated with scores in mathematics. Given that immigrants tend to study in schools where teachers have relatively smaller teaching loads, the school contribution to the total achievement gap is underestimated when using school fixed effects. Still, as Table 9 shows, the achievement gap between native and immigrant students in math would be only 1.37 points higher if the endowments of immigrant and native students were balanced in terms of class size and teaching loads. Thus the attenuation of the estimated upper bound of the school contribution to the achievement gap is unlikely to be an important issue. Even accounting for the effect of class size and teaching load, the total effect of the rest of school characteristics on the achievement gap would be slightly higher than seven points, which is equivalent to 13 % of the gap. In reading and sciences, attenuation of the estimated school contribution to the achievement gap is even smaller.

Next, we analyze whether the achievement gap can be explained by the proportion of immigrant peers in school and the corresponding crowding out of native students with favorable family background to other (often private) schools. Here again we are not interested in answering the question of whether peer effects actually exist. The estimation of peer effects is a tricky issue since it runs into the well-known “reflection problem (Manski 1993): the proportion of immigrant peers might capture the effect of unobserved differences in individuals’ own characteristics, as well as in school quality and other peers’ characteristics. Instead, we are interested in characterizing a likely upper bound of the effect of immigrant peers after controlling for a number of school characteristics.

We find that the proportion of immigrant peers is negatively associated with individual scores (column 3 in Tables 11, 12, 13). A native student who has no immigrants in the class obtains up to 15 points more than a student who has half of her classmates from immigrant origin. This figure is equal to about 20 points in the case of immigrant students (columns 4). In order to disentangle the effect of immigrant peers from the crowding out effect of native peers with wealthy and educated parents, we also control for the family background of native peers (columns 5 and 6). The idea is that the lack of native peers from an advantaged background might itself be detrimental to students’ performance and, at the same time, might be correlated with the presence of immigrants in school. We observe there is a significant positive correlation between parental education of native peers and achievement: native students whose native peers have parents with an additional year of schooling achieve about 12 points more in all PISA domains. For immigrant students this figure is a bit smaller—about 7–8 points—but nevertheless it is statistically significant. After controlling for the crowding out of native peers, the effect of the proportion of immigrant students becomes not statistically different from zero, both for the achievement of immigrant and native students. Interestingly, the estimated advantage of private and semi-private schools over public schools also becomes insignificant after accounting for native peers’ background (with the exception of the effect of private schools on the math scores of immigrants). Panel (a) of Table 9 shows that the contribution of peers’ characteristics might account for up to 6–7 points of the achievement gap and, after conditioning on peers’ characteristics, school ownership or other observable school characteristics do not make a significant difference.

We then perform the same analysis separately for immigrants from Latin America and the rest of immigrant students (columns 7 and 8 of Tables 11, 12, 13). We observe that for both groups of immigrants the proportion of immigrants in school is not significantly correlated with achievement after controlling for native peers’ background. In contrast, the native peers’ background is an important predictor of success for both groups of immigrants. Generally, there are no differences in the performance of students studying in public and semi-private schools (with the exception of Spanish-speaking immigrants who tend to do relatively better in private schools). Overall, school ownership cannot explain the underperformance of either group of immigrant students (Table 9, panels b and c). For both groups, the most important factor seems to be related to immigrant students’ disadvantage in terms of peers’ characteristics.

To sum up, the contribution of the segregation of immigrant and native students across schools to the achievement gap seems to be pretty limited. Moreover, immigrant students seem to have a relative advantage at least in terms of such characteristics as class size and teachers’ teaching loads, without which the achievement gap would have been slightly larger. The remaining school characteristics might explain at most one seventh of the gap. The most important school characteristics in this respect seem to be related to classmates’ characteristics; and there are no differences between Latin American students and the rest of immigrant students in this respect.Footnote 14

4.2.2 Family characteristics and the achievement gap

In this section we first analyze the extent to which observed individual characteristics might contribute to the achievement gap between native and immigrant students. Second, we quantify how the estimated school fixed effects described in the previous section are robust to controls for individual characteristics. In fact, due to potential sorting of students with different characteristics into different schools, the estimated school contribution is likely to be an overestimate. The observed school effect might partially capture the role of parents’ characteristics or even individual talent. The robustness of this estimate to individual controls might provide information on the scale of this overestimation.

Individual characteristics appear to be strongly correlated with performance (Table 14). Female students of both native and immigrant origin perform significantly better than their male counterparts in reading proficiency, whereas only native female students perform significantly worse than male students in mathematics and sciences. Even if students in the sample are roughly between 15 and 16 years old, relatively older students tend to have significantly better scores. Parents’ education is significantly related to students’ performance. A child whose both parents hold a university diploma obtain scores about 50 points higher than a child whose both parents have not achieved a diploma of obligatory education. Children of high skilled, white-collar workers obtain on average 17–19 points more than children of low skilled, blue-collar workers. While the effect of parental occupation is stronger for immigrants, the number of books at home and the availability of a computer and a study desk are all strong predictors of achievement both for immigrant and native students.

Around 55 % of the estimated gap between immigrants and natives is attributable to these observable individual characteristics (panel a of Table 9). Parental occupation and family possessions account for most of this effect.

Finally, we analyze the robustness of the estimated school contribution to the achievement gap to controlling for individual characteristics. We observe that the size and the significance of the school contribution (as measured by school fixed effects) is reduced after controlling for individual characteristics. The estimated contribution of schools to the gap drops by about 40 %, and in the sciences it becomes not statistically different from zero.

In the last specification we analyze the contribution of all observable school characteristics after controlling for individual characteristics. Generally, the inclusion of individual controls does not significantly affect the estimates for any particular group of school characteristics. Peer characteristics still explain most of school contribution to the achievement gap.

To sum up, we are able to attribute up to 55 % of the immigrant-native achievement gap to only few observable individual characteristics. This stands in sharp contrast with the assessed contribution of schools to the achievement gap: even school fixed effects can explain at most 13 % of the gap. Even this small estimate of the school contribution is generally not robust to the inclusion of individual controls.

5 Conclusions

This paper contributes to the analysis of the phenomenon of immigrant students’ relatively low performance in the compulsory education system in Spain. According to PISA OECD data, an average immigrant student obtains scores that are about 70 % of the standard deviation lower than that of native students. In this paper we analyze this gap between immigrant and native students, assessing the rate of catching up associated with the time that immigrants live in Spain and characterizing the role of segregation of immigrant and native students across schools.

We find that, on average, immigrant students tend to improve their performance with time they stay in Spain. Still, even students who were born in immigrant families in Spain or who were brought to Spain soon after their birth perform, on average, worse than native students. The rate of catching up is faster for immigrants who do not come from Spanish-speaking countries. On the other hand, students from Latin America do not tend to catch up with native students, despite their initial linguistic advantage over the rest of immigrants. This result suggests that the knowledge of local language per se does not guarantee better educational dynamics for immigrant students and that more understanding is needed of the factors affecting educational performance of students from Latin America.

A further analysis of the determinants of educational achievement suggests that more than half of the achievement gap between native and immigrant students can be attributed to the difference in only a few observable family characteristics, such as parental occupation and home possessions. At the same time, all between-school variation of the immigrant-native achievement gap is no more than one seventh of the gap. School resources provide even less of an explanation for the underachievement of immigrants from Latin America. Naturally, the true school contribution is likely to be even smaller than the total between-school variation of the gap, since it is likely that students with different family characteristics sort in different schools and it is family background, and not school characteristics, that explain a part of the total school effect.

Among specific school characteristics, the segregation of immigrant and native students across public and private schools can partially explain immigrants’ relative underperformance. At a first glance, private and semi-private schools appear to generate higher educational outcomes, so the fact that immigrant students are much less likely to attend private schools seems to negatively affect their relative performance. However, the performance differences between private, semi-private and public schools are themselves largely explained by the characteristics of native students attending these schools. It seems that the segregation of immigrant and native students across public and private schools occurs along with the crowding out of native students (from relatively more favorable backgrounds) away from public schools and schools with higher ratios of immigrant students. Once we account for the background of native peers at school, we observe no significant differences in performance across students attending public and private schools or across schools with a different proportion of immigrant students. In other words, it seems that the lack of native peers from relatively more advantageous families is at least as likely to be an explanation of immigrants’ underachievement as the higher ratio of immigrants among their peers and the lack of other school resources available to students in private schools.

The results of our analysis are, on the one hand, reassuring since they indicate that the existent compositional differences in school attendance between immigrants and natives do not generate substantial negative performance effects. On the other hand, they suggest that in order to solve the problem of immigrants’ underachievement, the range of practices currently used in Spanish schools is not sufficient. Other policies could thus be tried, perhaps including those that target the learning environment in immigrants’ families and rely on early intervention practices (Heckman et al. 2010).

Notes

Immigrant students also seem to progress more slowly during all stages of the educational system and they are more likely to drop out of this system (Fig. 5).

The available empirical evidence suggests that peer quality tends to affect students’ educational achievement (Hoxby 2000b; Sacerdote 2001; Hanushek et al. 2003; Angrist and Lang 2004; Carrell et al. 2009), including the one of immigrant students (Brunello and Giannini 2004; Hanushek and Wossmann 2006; Hanushek and Rivkin 2009). However, policy interventions based on this evidence should be designed with caution (Carrell et al. (2013)).

In the literature the importance of school resources and educational practices for student achievement is well-documented: school resources (Angrist and Lavy 1999; Hanushek 1999; Hoxby 2010a), school ownership (among others Altonji et al. 2005; Angrist et al. 2006, Friske and Ladd 2000), and streaming by ability (Entorf and Lauk 2006) are likely to matter for student achievement.

Children born in Spain can obtain Spanish nationality after one year of residence in Spain. In 2008, only 59 % of children of age between 0–5 years with both foreign parents had a foreign nationality. The impact of immigration in Table 1 is undervalued due to the fact that most children aged between 0 and 5 years whose parents are foreigners already have Spanish nationality. In Table 2 we show how the proportion of immigrants varies according to how immigrants are defined.

The compulsory schooling age was increased from 14 to 16 in 1992.

Here immigrants are defined as those individuals who were born abroad and whose both parents were born abroad.

See Table 10 for the definition of all variables used in our analysis.

The difference in grade attendance could be considered as another indicator of performance. However, it also signals that immigrant students on average have been exposed to different curricula than native students. Therefore, the poor achievement of immigrants in PISA might be partially a result of this latter phenomenon, and not of their poor learning. When we repeat the analysis adding a control for the grade attended by students, the predicted gap between native and immigrant students reduces by half. The gap, however, does not disappear completely. The predictions of the next sections concerning the relative importance of individual and school characteristics for explaining the gap remain the same. Given that, according to PISA, the content of the tests does not generally require any specific knowledge that is acquired by students in the 10th grade, the results presented in this paper are not conditioned on grade attendance.

In Spain, students are normally kept together within the same class in order to attend the main courses.

Public schools are underrepresented in the PISA sample: only 54 % of students in our sample attend public schools compared to 66 % of students in the official statistics. This bias in the sample design is captured by the stratification weights, which we use throughout the analysis below.

The Spanish edition of PISA survey does not provide information on the nationality of immigrant students and their parents. The students whose mother tongue is Spanish are likely of be of Latin American origin.

Predicted scores for these students at the age of 16 could be calculated as \(\overline{S}^d+\beta _1(16-\overline{YearsInSpain})\), where \(\overline{S}^d\) is the average score of all immigrant students in domain \(d\) and \(\overline{YearsInSpain}\) is the number of years that an average immigrant student lived in Spain. In mathematics this predicted score is equal to 477.21, in reading—to 457.06, and in sciences—to 491.40.

In unreported results we control for post-immigration family characteristics, but they also fail to explain the tendency among Latin American students to not catch up.

Note that the estimated effect of peers’ characteristics might at least partially suffer from the“reflection problem. So schools are likely to account for even less than one seventh of the achievement gap.

References

Altonji JG, Elder TE, Taber CR (2005) Selection on observed and unobserved variables: assessing the effectiveness of catholic schools. J Polit Econ 113(1):151–184

Anghel B, Cabrales A (2010) Determinants of success in primary education in Spain. FEDEA working paper 2010-20

Angrist J, Bettinger E, Kremer M (2006) Long-term educational consequences of secondary school vouchers: evidence from administrative records in Colombia. Am Econ Rev 96(3):847–862

Angrist J, Lang K (2004) Does school integration generate peer effects? Evidence from Boston’s Metco program. Am Econ Rev 94(5):1613–1634

Angrist J, Lavy V (1999) Using Maimonides rule to estimate the effect of class size on scholastic achievement. Quart J Econ 114(2):533–575

Brunello G, Giannini M (2004) Stratified or comprehensive? The economic efficiency of school design. Scott J Polit Econ 51(2):173–193

Calo-Blanco A, Villar Notario A (2010) Quality of education and equality of opportunity in Spain: lessons from Pisa. Fundación BBVA working paper 6-2010

Carrell SE, Fullerton RL, West JE (2009) Does your cohort matter? Estimating peer effects in college achievement. J Labor Econ 27(3):439–464

Carrell SE, Sacerdote BI, West JE (2013) From natural variation to optimal policy? The importance of endogenous peer group formation. Econometrica 81(3):855–882

Ciccone A, Garcia-Fontes W (2009) The quality of the Catalan and Spanish education systems: a perspective from PISA. IESE Business School working paper, WP-810

Entorf H, Lauk M (2006) Peer effects, social multipliers and migrants at school: an international comparison. IZA discussion paper, No 2182

Entorf H, Minoiu N (2005) What a difference immigration policy makes: a comparison of PISA scores in Europe and traditional countries of immigration. Ger Econ Rev (Blackwell Publishing) 6(3):355– 376

Hanushek EA (1999) Some findings from an independent investigation of the tennessee STAR experiment and from other investigations on class size effects. Educ Eval Policy Anal 21(2):143– 163

Hanushek EA, Kain J, Markman J, Rivkin SG (2003) Does peer ability affect student achievement? J Appl Econom 18(5):527–544

Hanushek EA, Wossmann L (2006) Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across countries. Econ J 116(510):C63–C76

Hanushek EA, Rivkin SG (2009) Harming the best: how schools affect the black–white achievement gap. J Policy Anal Manag 28(3):366–393

Heckman JJ, Moon SH (2010) The rate of return to the highscope PerryPreschool program. J Public Econ 94:114–128

Hoxby C (2000a) The effects of class size on student achievement: new evidence from population variation. Quart J Econ 115(4):1239–1285

Hoxby C (2000b) Peer effects in the classroom: learning from gender and race variation. NBER working paper no. 7867, Cambridge

Manski CF (1993) Identification of endogenous social effects: the reflection problem. Rev Econ Stud 60:531–542

Ministerio de educación y ciencia, Secretaría general de educación, Instituto de Evaluación (2006) PISA 2006. Informe Español, Programa para la Evaluación Internacional de Alumnos de la OCDE

Ministerio de educación y ciencia, Secretaría general de educación, Instituto de Evaluación (2010) PISA 2009. Informe Español, Programa para la Evaluación Internacional de Alumnos de la OCDE

OECD (2008) Education at a glance 2008: OECD indicators

Sacerdote B (2001) Peer effects with random assignment: results for Dartmouth roommates. Quart J Econ 116(2):681–704

Schneeweis N (2006) How should we organize schooling to further children with migration background? Economics working papers 2006-20. Department of Economics, Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria

Silaghi FR (2011) Immigration and peer effects: evidence from primary education in Spain. Master thesis CEMFI no. 1103

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions received from Victor Aguirregabiria (editor), the anonymous reviewer, Manuel Bagues, Michele Boldrin, Antonio Cabrales, Jose Ignacio García, Sergi Jiménez, and participants at the European Economic Association (EEA) Congress, the European Association of Labour Economists (EALE) conference, the Spanish Economic Association (SAE) Congress, and the FEDEA workshop on the economic effects of immigration. We also acknowledge the financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Project ECO2008-06395-C05-05.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd.Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zinovyeva, N., Felgueroso, F. & Vazquez, P. Immigration and student achievement in Spain: evidence from PISA. SERIEs 5, 25–60 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-013-0101-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-013-0101-7