Abstract

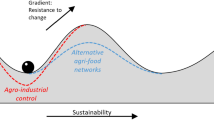

Today’s domestic US food production is the result of an industry optimized for competitive, high yielding, and high-growth production for a globalized market. Yet, industry growth may weaken food system resilience to abrupt disruptions by reducing the diversity of food supply sources. In this paper, we first explore shifts in food consumption toward reliance upon complex and long-distance food distribution, food imports, and out-of-home eating. Second, we discuss how large-scale, rapid-onset hazards may affect food access for both food secure and insecure households. We then consider whether and how regional food production might support regional food resilience. To illustrate these issues, we examine the case of western Washington, a region not only rich in agricultural production but also threatened by a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami. Such an event is expected to disrupt transportation and energy systems on which the dominant food distribution system relies. Whether a regional food supply—for the purposes of this paper, defined as food production in one or adjacent watersheds—can support a broader goal of community food resilience during large-scale disruption is a key theme of our paper. The discussion that ensues is not meant to offer simplistic, localist solutions as the one answer to disaster food provision, but neither should regional food sources be dismissed in food planning processes. Our exploration of regional farm production, small in scale and flexible, suggests regional production can help support food security prior to the arrival of emergency relief and retail restocking. Yet in order to do so, we need to have in place a robust and regionally appropriate food resilience strategy. This strategy should address caloric need, storage, and distribution, and, in so doing, rebalance our dependence on food supplied through imports and complex, domestic supply chains. Clearly, diversity of food sourcing can add redundancy and flexibility, allowing more nimble food system adaptation in the face of disruption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Regardless of type of disaster, evacuation and stockpiling are premised on sufficient resources. For low-income households, stockpiling and evacuation may be unaffordable. Households without private transportation must rely upon social networks or already overwhelmed public and emergency transport to evacuate. Many often choose to ride out the events at home, as was seen in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina.

The World Health Organization and other United Nations agencies routinely complete rapid food security assessments of endemic and disaster-induced food insecurity in low-income countries. While crucial for humanitarian response to these events, the differences in subsistence, income, and spatial distribution of population make these assessments less useful for deducing disaster impacts to food access in the USA.

A less extreme case of food shortage made international news when New Zealanders faced a shortage of Marmite spread several months after the 2011 Christchurch earthquake.

An import “line,” whether it accounts for one or one thousand items, is a data element provided by an import broker.

The loss estimates discussed are based upon 90th percentile damage estimates—indicating a damage state with only a 10 % estimated change of being exceeded. This credible worst-case scenario is used for regional planning purposes in Washington and Oregon and helps to account for secondary impacts of landslides and aftershocks not well modeled in the loss estimation program.

Tsunami wave heights are expected to be much smaller and less damaging by the time they reach Seattle, Tacoma, and other urban centers within the Salish Sea; Vancouver Island will refract much of the wave energy back out into the Pacific Ocean basin.

Loss modeling of injuries is based upon the time of day. Earthquake events that occur in the middle of the night tend to cause the least injury and death in the USA, as most people are in the relative safety of their homes. Events that occur during the daytime, especially during commuting hours, are expected to increase injuries by an order of magnitude or more.

Existing observations of survivors of famine and concentration camps and other extreme events indicate that most healthy adults can survive without food for approximately 30 days and without water for several days (Packer 2002). While it is comforting to think that few healthy adults would die from lack of food access in a Cascadia event, the aim of community disaster planning around food security should be that ensuring survivors do not experience a dramatic increase in food insecurity during the immediate aftermath and recovery from these events.

A statewide assessment (Green and Cornell 2015) suggests high quantities of food that are produced and stored in eastern Washington. Stone fruits, grains, and potatoes produced on the Columbia Plateau and wheat and legumes in the Palouse could contribute to Washington state food security. However, transporting such food items to affected communities in western Washington would be hampered by bridge damage and landslides in mountain passes and along the I-5 corridor.

Several seafood processors and cold storage facilities along the Pacific Coast are within the tsunami inundation zone.

Note that virtually all the hazelnuts in the USA are produced in Oregon as reported by the Agricultural Marketing Resource Center and USDA ERS statistics on fruit and tree nuts, although Washington state is gaining ground. Hazelnuts in Oregon would necessarily better support affected communities in that state.

Due to prohibitions on use of federal monies, food stored in contracted warehouses, such as food banks, may not be used for disaster-related assistance until authorized. Note that the Washington State Emergency Operations Center would be responsible for deciding and communicating with the county food banks before contracted warehouses could modify their standard food distribution protocol.

Also important to consider in terms of food delivery is the concept of “emergency relief chains,” i.e., links between customer services and nonprofit, nonroutinized supply chains. Examples attest to the ability of regional food networks to provide scheduled food assistance, such as school lunch programs (Sanger and Zenz 2004). In terms of short-term relief, infrastructure and relief program organization remain challenges. Better understanding of what motivates such “chains” in a humanitarian context is needed (Oloruntoba and Gray 2009). Further, a more empathetic distribution system would also prioritize palatability in provision of usual and customary foods.

References

Belyakov A (2015) From Chernobyl to Fukushima: an interdisiciplinary framework for managing and communicating food security risks after nuclear plant accidents. J Environ Stud Sci 5:404–417

Berardi G, Green R, Hammond B (2011) Stability, sustainability, and catastrophe: applying resilience thinking to U.S. agriculture. Hum Ecol Rev 18:115–125

Clancy K, Ruhf K (2010) Is local enough? some arguments for regional food systems. Choices Magazine, Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. http://www.choicesmagazine.org/magazine/article.php?article=114 Accessed 20 May 2015

Colman-Jensen A, Gregory C, Singh A (2014) Household food security in the United States in 2013. Economic Research Report No. 173, United States Department of Agriculture. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err173.aspx. Accessed 27 May 2015

CREW (2013) Cascadia subduction zone earthquakes: a magnitude 9.0 earthquake scenario. http://crew.org/sites/default/files/cascadia_subduction_scenario_2013.pdf Assessed 27 May 2015

Dubbeling, M (2013) Linking cities on urban agriculture and urban food systems. RUAF Foundation. http://www.ruaf.org/sites/default/files/Text%20city%20food%20systems.pdf Accessed 16 Jul 2014

ERS (2015) U.S. food imports. USDA Economic Research Services. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/us-food-imports.aspx Accessed April 30 2015

Endres AB, Endres JM (2009) Homeland security planning: what victory gardens and Fidel Castro can teach us in preparing for food crises in the United States. Food Drug Law J 64:405–439

FEMA (2015) Cascadia rising: cascadia subduction zone earthquake and tsunami exercise scenario document. https://huxley.wwu.edu/sites/huxley.wwu.edu/files/media/Cascadia_Rising_low_1.pdf Assessed 13 April 2015

Fraser ED, Legwegoh A, Krishna KC (2015) Food stocks and grain reserves: evaluating whether storing food creates resilient food systems. J of Environmental Studies and Sciences 5:445–458

GAO (2007) Natural hazard mitigation: various mitigation efforts exist, but federal efforts do not provide a comprehensive strategic framework. Report GAO-07-403. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d07403.pdf Accessed 28 May 2015

Green R, Cornell J (2014) Regional market analysis of food security and regional resilience: whole community preparedness through local food production and distribution in Washington state. https://huxley.wwu.edu/sites/huxley.wwu.edu/files/media/2014_RI_REPORT_FEMA_Food_Security_0.pdf Accessed 1 September 2015

Guthrie J, Lin B, Okrent A, Volpe, R (2013) Americans’ food choices at home and away: how do they compare with recommendations? USDA Economic Research Service. http://ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2013-february/americans-food-choices-at-home-and-away.aspx#.U76pH1a4mlJ Accessed 10 June 2014

Hammond B, Berardi G, Green R (2013) Resilience in agriculture: small- and medium-sized farms in northwest Washington state. J Sustainable Agric 37:316–339

Hayes RC, Newell MT, DeHaan LR, Murphy K, Crane S, Norton MR, Wade LJ, Newberry M, Fahim M, Jones SS, Cox TS, Larkin PJ (2012) Perennial cereal crops: an initial evaluation of wheat derivatives. Field Crops Res 133:68–89

Higginbotham RW, Jones SS, Carter AH (2011) Adaptability of wheat cultivars to a late-planted no-till fallow production system. Sustainability 3:1224–1233

Hills K, Corbin A, Jones S (2011) Rebuilding the grain chain: stories from the coastal Pacific Northwest. Rural Connections Sept. 32-36. http://wrdc.usu.edu/files/publications/publication/pub__9828019.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2015

Hills KM, Goldberger JM, Jones SS (2013) Commercial bakers and the relocalization of wheat in western Washington state. Agr Hum Values 30:365–378

Hobor G (2015) New Orleans’ remarkably (un) predictable recovery: developing a theory of urban resilience. Am Behav Sci 59:1214–1230

Hori M, Iwamoto K (2014) The run on daily foods and goods after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake: a fact finding analysis based on homescan data. Japanese Political Economy 40:69–113

HVRI (2013) U.S. Hazard losses 1960-2013. http://hvri.geog.sc.edu/SHELDUS/index.cfm?page=products#State Accessed June 11, 2015

IRS (2014) Food industry overview. Report LMSB-04-0207-018. http://www.irs.gov/Businesses/Food-Industry-Overview. Accessed 15 Jul 2014

Jakumar N, Snapp S, Murphy K, Jones SS (2012) Agronomic assessment of perennial wheat and perennial rye as cereal crops. Agron J 104:1716–1726

Jones SS (2012) Kicking the commodity habit: on being grown out of place. Gastronomica 12:74–77

Kloppenburg J, Hendrickson J, Stevenson GW (1996) Coming in to the foodshed. Agr Hum Values 13:33–42

Low S, Vogel S (2011) Direct and intermediated marketing of local foods in the United States. USDA Economic Research Report No. 128. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/138324/err128_2_.pdf Accessed 23 May 2015

Maguire LS, O’Sullivan SM, Galvin K, O’Connor TP, O’Brien NM (2004) Fatty acid profile, tocopherol, squalene and phytosterol content of walnuts, almonds, peanuts, hazelnuts and the macadamia nut. Int J Food Sci Nutr 55:171–178

McColl G, Burkle F (2012) The new normal: twelve months of resiliency and recovery in Christchurch. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 6:33–43

Moises C (2007) Brown bag blues: New Orleans residents can’t buy fresh produce. New Orleans CityBusiness 1.

Mundorf AR, Willits-Smith A, Rose D (2015) 10 years later: changes in food access disparities in New Orleans since hurricane Katrina. J Urban Health 92:605–610

Murphy K, Hoagland A, Reeves P, Baik B, Jones S (2009) Nutritional and quality characteristics expressed in 31 perennial wheat breeding lines. Renew Agr Food Syst 24:285–292

National Agricultural Statistics Service (2012) The pride of Washington state. United States Department of Agriculture. http://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Washington/Publications/wabro.pdf Accessed 30 Jun 2014

National Agricultural Statistics Service (2013) Value of Washington’s 2012 agricultural production surpasses previous year’s record high. United States Department of Agriculture. http://agr.wa.gov/AgInWa/docs/2012WaAgValuesUSDAPressRelease.pdf Accessed 7 Jun 2014

Oliver-Smith A (1999) Peru’s 500-year earthquake: vulnerability in historical context. In: Oliver-Smith A, Hoffman S (eds) The angry earth: disaster in anthropological perspective. Routledge, New York, pp 74–88

Oloruntoba R, Gray R (2009) Customer service in emergency relief chains. Int J Phys Distrib 39:486–505

Packer RK (2002) How long can the average person survive without water? Sci Am. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-long-can-the-average Accessed 15 June 2014

Poppendieck J (1994) Dilemmas of emergency food: a guide for the perplexed. Agr Hum Values 11:69–76

Robinson K (2014) Annual report, Food Safety and Consumer Services, Washington State Department of Agriculture. http://agr.wa.gov/FoodProg/docs/FSCS_Annual_Report.pdf Accessed 1 Oct 2015

Rose A, Wing IS, Wei D, Avetisyan M (2012) Total regional economic losses from water supply disruptions to the Los Angeles county economy. Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation. http://www.laedc.org/reports/WaterSupplyDisruptionStudy_November2012.pdf Accessed Sept 3 2015

Ruhf K (2015) Regionalism: a New England recipe for a resilient food system. J Environ Stud Sci. doi:10.1007/s13412-015-0324-y

Sanger K, Zenz L (2004) Farm-to-cafeteria connections: market opportunities for small farms in Washington state. Washington State Department of Agriculture. http://agr.wa.gov/Marketing/SmallFarm/docs/102-FarmToCafeteriaConnections-Web.pdf Accessed 20 May 2015

Seneff S, Wainwright G, Mascitelli L (2011) Is the metabolic syndrome caused by a high fructose, and relatively low fat, low cholesterol diet? Arch Med Res 7:8–20. doi:10.5114/aoms.2011.20598

Selfa T, Qazi J (2005) Place, taste or face-to-face? Understanding producer-consumer networks in “local” food systems in Washington state. Agr Hum Values 22:451–464

Steinberg T (2000) Acts of god: the unnatural history of natural disaster in America. Oxford University Press, New York

Taylor A (2012) Hurricane Sandy: the aftermath. The Atlantic http://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2012/11/hurricane-sandy-the-aftermath/100397/ Accessed 12 June 2015

Thomas JA, Mora K (2014) Community resilience, latent resources and resource scarcity after an earthquake: is society really three meals away from anarchy? Nat Hazards 74:477–490

U.S. Dept. of Commerce (2008) Food manufacturing. US DOC Industry Report NAICS 311. http://trade.gov/td/ocg/report08_processedfoods.pdf Accessed 8 Jun 2014

Washington State Dept of Health (2012) Report on Washington’s food system response to executive order 10-02. With Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, the Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the Washington State Department of Agriculture. http://depts.washington.edu/uwcphn/work/php/Washington%27s_Food_System_Report_01_17_12.pdf Accessed 10 Mar 2015

WHO (2000) The management of nutrition in emergencies. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2000/9241545208.pdf Assessed 27 May 2015

Wisner B, Blaikie P, Cannon T, Davis I (2003) At risk: natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters, 2nd edn. Routeledge, New York

Wood N, Soulard C (2008) Variations in community exposure and sensitivity to tsunami hazards on the open-ocean and Strait of Juan de Fuca coasts of Washington. USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5004

Wood N, Schmidtlein M (2013) Community variations in population exposure to near-field tsunami hazards as a function of pedestrian travel time to safety. Nat Hazards 65:1603–1628

Weber CL, Matthews SH (2008) Food miles and the relative climate impacts of food choices in the United States. Environ Sci Technol 42:3508–2513

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paci-Green, R., Berardi, G. Do global food systems have an Achilles heel? The potential for regional food systems to support resilience in regional disasters. J Environ Stud Sci 5, 685–698 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-015-0342-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-015-0342-9