Abstract

This paper examines the determinants of mathematics performance of first-year students enrolled in several business administration and economics study programmes at the beginning of the first semester (T1) and nine weeks later (T2). A simple model of educational production, which is developed in accordance with the model of Schrader and Helmke (2015), is used as the theoretical basis for our analysis. As predictors, we choose numerous variables which represent study-specific, socio-economic and biographical, motivational and cognitive aspects as well as variables that reflect the learning behaviour, working habits and the use of voluntary support (e.g., tutorials). Data from two skills tests and two surveys that were carried out at the University of Kassel in the winter semester 2011/12 and regression techniques are used to identify the determinants of mathematics performance. It turns out that the type of school graduation, final school grades, pre-knowledge and self-belief are essential determinants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Motivation

Mathematics plays a growing role in business administration and economics (B&E). In particular, the increasing importance of quantitative methods in both science and practice has led to curricula in B&E study programmes at universities that include at least one or two modules in mathematics and statistics (Voßkamp 2016). Moreover, starting with Paul Samuelson’s textbook Economics (Samuelson, 1948/1997) – to acknowledge one milestone – the importance of mathematics has increased in all areas of B&E. A short look at widely used textbooks in economics illustrates this development (see, e.g., Blanchard and Johnson 2012, and Pindyck and Rubinfeld 2013). The mathematics used in B&E courses covers a wide range of topics from analysis (in particular calculus) to linear algebra. The textbooks on mathematics for economic analysis by Simon and Blume (2010), Sydsaeter et al. (2012) and Chiang and Wainwright (2005) give an idea of the mathematics topics taught in B&E study programmes at the university level.

In the light of this, it seems to be clear that students with stronger mathematical skills obtained at secondary schools will do better in B&E study programmes. For example, a student’s grade in mathematics at the end of the secondary school has a significant impact on the probability of passing a bachelor or master exam in B&E (see, e.g., Heublein 2014). Anderson et al. (1994) identified background knowledge of calculus as one of the most important determinants of the probability of dropping introductory economics courses in the first semester. It “is a well-established finding in the literature on economic education” that mathematical skills are a key determinant of study progress in economics (Arnold and Straten 2012, p. 33). Consequently, from the perspective of B&E students as well as the perspective of B&E faculties, a high level of secondary school mathematics is desirable.

However, many mathematics educators are confronted with inadequate first-year students’ mathematical skills. “This is often referred to as the ‘Mathematics Problem’ and relates to students entering third-level whose mathematics at school level is insufficient for the demands of their third-level Service mathematics courses and careers” (Liston and O’Donoghou 2009, p. 77). In Bausch et al. (2014) and Hoppenbrock et al. (2016) numerous studies are published which report the deficits of first-year students’ mathematical skills at German universities. In B&E study programmes in particular deficits are reported to be serious. Empirical research on B&E students at the University of Kassel supports these results (Voßkamp and Laging 2014; Laging and Voßkamp 2016; Sonntag 2016). Results from skills tests at the beginning of studies show dramatic deficits. Moreover, skills tests after several weeks show that in many cases first-year students are not able to compensate deficits, despite the substantial voluntary support (e.g., remedial courses) offered to the students.

Among mathematics educators, these facts are often communicated with a dramatic tenor. Many mathematics educators like to point out that in earlier times things went better, adding conjectures on negative changes with respect to the students’ characteristics (e.g., decreasing pre-knowledge and motivation) and the negative impact of institutional changes (e.g., the implementation of new educational standards).

The transition from school to university is a stressful, demanding, life-changing experience that requires many changes (Clark and Lovric 2008, p. 29). Especially the secondary-tertiary transition in mathematics education has become a major issue with different focuses and different theoretical approaches (Gueudet 2008). Most of research on transition takes place in a few specialized areas (Thomas et al. 2012). Clark and Lovric (2008) postulate the absence of a theoretical model in research of transition. They provide an anthropological approach based on the ‘rite of passage’ concept and reflect the different kinds of changes students are confronted with. Gueudet (2008) structures mathematical educational literature about secondary-tertiary transitions into three views of transition: Research belonging to ‘Advanced Mathematical Thinking’ (AMT), research focussing on proof and language and research focussing on didactical transpositions.

Therefore, most studies focus on the nature of mathematics and how it is taught at university level. However, there are only very few studies that analyse determinants of first-year students’ achievement, especially determinants of mathematical skills of first-year students (e.g. Hailikari et al. 2008; Pajares and Miller 1994). In contrast, there are many studies on the determinants of secondary school achievements. The meta-analysis ‘Visible Learning’ (Hattie 2009) gives a good overview of determinants of school achievements based on over 800 meta-analyses. However, it is questionable whether the results of these studies are applicable to understand the causes and consequences of the achievements in mathematics in higher education. In particular, the impact of study-specific, socio-economic and biographical, motivational and cognitive aspects as well as aspects that reflect the learning behaviour, working habits and the use of voluntary support (e.g., tutorials) is unclear.

Therefore, studies on higher education are needed in order to reveal the determinants of the mathematical competencies of first-year students. Moreover, the interactions between all these variables and further variables have to be analysed. The knowledge of these relationships is necessary to identify effective and efficient interventions in order to increase the success of students.

Purpose of the Study

In this article we will contribute to the above mentioned issues. In a first step, we will develop a simple model of student achievement in higher education based on well-known theories from various scientific disciplines. Our model which can be interpreted as a model of educational production provides a link between the mathematical skills (output variable) and several explanatory variables (input variables).

In a second step, we will test the model empirically. For this purpose well-known methods from empirical educational research (especially regression methods) will be applied. We used two instruments to obtain data: a skills test on basic mathematics and a questionnaire with questions concerning students’ socio-economic and biographical background, motivational aspects, learning behaviour, working habits and the use of voluntary support services. The sample consists of 447 B&E students enrolled at the University of Kassel; all students were enrolled in a first-year course, ‘Mathematics for B&E’, in the winter semester 2011/12. Both instruments were used (in variants) at two points of time: at the beginning of the course (time T1) and in the ninth week of the course (time T2).

Outline

We start with a brief overview of relevant empirical literature. Then, we discuss theoretical contributions related to our purposes. On this basis, we develop a simple model of educational production. After elaborating on the quantitative methods applied, the data and variables used, we present and discuss the results. The paper ends with a conclusion including summary remarks, statements on limitations, implications as well as an outlook on further research.

Empirical Background

Previous research has highlighted several determinants of academic performance. An overview of important factors for school achievement is given in the synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses in ‘Visible Learning’ by Hattie (2009). Hattie structures over 130 potential determinants around six factors: the child, the home, the school, the curricula, the teacher and the approaches to teaching. Most of the meta-analyses included combine different kinds of academic performance. A focus on only mathematical performance and constructs related to mathematics can change the importance of factors. For instance, a more recent meta-analysis about the relationship of maths self-efficacy and maths performance in school and university (Laging 2016a) produced a considerable larger effect size than the synthesized meta-analyses by Hattie (2009).

Most of the studies and meta-analyses are focussed on single aspects, but there are very few studies that analyse these variables simultaneously (Schiefele et al. 2003), especially in the case of higher education.

Moreover, many studies related to secondary schooling show the relevance of many predictors in detail. PISA 2000 data confirmed socio-economic background as one of the strongest predictors of performance (OECD 2003) with an exceedingly strong relation in Germany (Stanat and Lüdtke 2013). Also, effects of family characteristics, student motivation and country resources on mathematics achievement in 41 countries are analysed by Chiu and Xihua (2008) with the PISA 2000 database. The multilevel analyses revealed that 44 % of the variance in students’ mathematics scores occurred at student level, 25 % at school level and 31 % at country level. Multilevel regression with these variables explained 36 % of the variance in students’ mathematics scores. The results indicate the importance of family characteristics. Students living with two parents from families with greater socio-economic status, more investment in educational resources and more family involvement obtain higher scores in mathematics performance.

Intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy and self-concept were also found to be significant positive predictors of mathematics achievement. Analysing the PISA data of Turkish students, a factor analysis with 14 items from a student questionnaire revealed four factors accounting for approximately 34 % of the variance in mathematics scores (Demir et al. 2009): student background (e.g., economic, social and cultural status, HISEI), self-related cognitions in mathematics (self-concept, interest, self-efficacy and anxiety in mathematics), learning strategies and school climate. Multivariate regression revealed that student achievement is predominantly influenced by student background and self-related cognitions in mathematics (Demir et al. 2009).

In higher education, “various predictors, including precollege characteristics, traditional assessments of one’s cognitive abilities, and a battery of psychological and non-cognitive variables” (Strayhorn 2013, p. 17) have been investigated to explain academic achievement. As “academic preparation is the most significant predictor of academic achievement in higher education” (Strayhorn 2013, p. 18), past grades in school are important predictors of academic achievement in higher education. In multiple regression analyses Liston and O’Donoghou (2009) reveal mathematical competencies and past experiences in terms of results of final maths exams as the strongest predictors of mathematics marks in the first semester.

The amount of time and effort students devoted to their study influences their achievement in college (Kuh and Hu 1999; Strayhorn 2013). A meta-analysis to predict college performance shows that ACT/SAT scores and high school GPA were the strongest predictors, but academic self-efficacy and achievement motivation contribute meaningfully to the prediction of college performance (Robbins et al. 2004). Hailikari et al. (2008) revealed domain-specific prior knowledge as strongest predictor of students’ achievement on a university mathematics course using structural equation modelling. Prior knowledge test performance was strongly influenced by academic self-beliefs (expectation of success, self-efficacy, self-perception of mathematics ability).

Anthony (2000) identified factors that students and lecturers perceived as most influential for students’ academic success or failure in mathematics courses in their first year at university. Factors that students and lecturers listed as most important in an open-ended survey were categorized in factors related to lectures, courses, students and other external factors. Students and lecturers rated student factors most often, but lecturers placed more responsibility for success and failure on student factors than students did. The importance of identified factors was analysed using a Likert-type scale questionnaire and “motivation was seen by both students and lecturers as the most influential factor related to levels of success” (Anthony 2000, p. 9).

Theoretical Background

General Remarks

A general theory to explain the maths skills of first-year students does not exist. Therefore, we will start with theoretical approaches which were originally formulated to explain achievements of students at secondary schools.

Numerous theories from very different fields such as pedagogical psychology, sociology and economics can be used to explain student achievement at school. The sub-discipline classroom research alone has developed several different theories in the recent decades: personality paradigm, teaching style, process-product paradigm, expert paradigm, systemic model (for a review see Klieme 2006). In many theories the focus is set on only a few predictive variables, e.g. the personality paradigm focusses on teachers’ personality while the process-product paradigm focusses on teachers’ behaviour in the classroom.

We want to show a comprehensive picture of the determinants of mathematics performance. We, therefore, have to start with complex models which simultaneously take into account many variables. A model developed by Schrader and Helmke (2015) meets this criterion. This model, which is based on earlier works by A. Helmke, F. W. Schrader and F. E. Weinert (in particular Helmke and Weinert (1997)), will be the starting point for the development of our model.

The Model by Schrader and Helmke (2015)

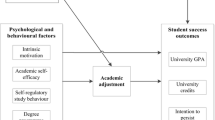

The complex model was formulated to explain school achievements (SA). The authors take into consideration six blocks of variables which directly or indirectly determine the pupil’s performance. These blocks are (see Fig. 1):

The structure of the model of F. W. Schrader and A. Helmke (See: Schrader and Helmke 2015, p. 49)

-

learning activities (LA)

-

individual motivational determinants (IMD)

-

individual cognitive determinants (ICD)

-

cultural background, media, peers (CB)

-

home learning environment (HLE)

-

school organisation, climate and classroom context (SO)

The authors postulate several important interdependencies. Learning activities (LA) decisively determine a pupil’s school achievement (SA) and are influenced by motivation (IMD) and cognition (ICD). Moreover, both are influenced by cultural background (CB). The environment at home (HLE) and at school (SO) also influences all these variables. Furthermore, there are also impacts from student achievements. Schrader and Helmke (2015) assume that the pupil’s achievements influence motivational (IMD) and cognitional (ICD) variables as well as the environment at home (HLE) and at school (SO). This model integrates many theories that can be used to specify the variables of the blocks. For example, the variables that are part of IMD can be identified by expectancy-value-theory (Wigfield and Eccles 2000). Constructs related to expectancies are for example self-concept and self-efficacy, constructs related to values are for example interest and goal orientation.

The Model

The Applicability of the Model of Schrader and Helmke for Higher Education Issues

The model of Schrader and Helmke (SH model) was originally designed to explain school achievement, but it integrates many theories that are not restricted to secondary schooling. For that reason, the model is transferable from a secondary schooling context to a higher education context. Most of the interdependencies which work in the case of secondary schooling are also relevant in the case of higher education at universities, but not all of them. The influence of HLE is assumed to be weaker because university students are more independent than secondary school students. On the other hand, motivational factors play a bigger role because attendance, invested time and effectiveness of learning in higher education is less controlled. Chemers et al. (2001) argue that “confidence in one’s relevant abilities (i.e., self-efficacy) and optimism play a major role in an individual’s successful negotiation of challenging life transitions” (p. 55). However, in the case of higher education the list of variables, which belong to the different blocks, has to be adjusted. And, before starting with empirical issues we have to specify scales and variables which represent the mentioned blocks.

Need for a Simplification of the Model

The SH model is a suitable theoretical basis that can be used to explain the mathematical achievements of first-year students. In principle, the SH model is also an adequate basis for empirical analysis. However, fundamental problems arise when the SH model has to be verified empirically because the quantitative methods which have to be applied require a large number of observations. In our case, the number of students represented in our data set is too small. The application of education production functions which implies a simplification of the SH model allows us to continue.

Education Production Functions (EPF)

The starting point of the EPF approach (see, e.g., Brewer et al. 2010) is the original concept of the production function: goods (e.g. cars) are produced through the use of factors of production (e.g., labour, capital and intermediate products) (see Fig. 2).

As a rule, it is assumed that the relationship between output variable and input variables can be represented mathematically by using functions (e.g., Cobb-Douglas functions and linear functions).

The EPF approach assumes that an educational output (e.g., a certain grade or a level of students’ performance in mathematics) is a result of a production process where educational inputs (e.g., investment of time, motivation, quality of school) determine the output. The most crucial problem with EPF concerns the choice of variables. In standard production theory it is clear which variables have to be taken into account for both output variable and input variables. Moreover, the measurement of the variables is straightforward because widely accepted accounting principles are applied (in Europe: European systems of accounts (ESA); Eurostat 2013).

With EPFs, things are more difficult. First, for many input and output variables, there is no consensus for measurement of the variables. Second, there is no clearly defined set of input variables which have to be taken into account if we look for the determinants of a specific educational output variable. Therefore, the application of EPFs is associated with heuristic and empirical methods in order to make the approach valuable.

Operationalisation of Input and Outcome Variables

Because of this background, we are working with a simple model which covers the main features of the SH model. In particular, we use the EPF approach to link student achievement and important predictors.

As output variable, we choose the mathematical achievement of first-year students. As input variables, we select variables representing most of the blocks of determinants considered in the SH model. We add study-specific variables in order to transfer the model to the higher education case. These variables can be assigned to six blocks:

-

study-specific variables (S)

-

socio-economic and biographic variables (B)

-

motivational factors (M)

-

learning strategies (L)

-

working habits (W)

-

use of support (U)

Figure 3 shows the basic structure of the model. In the next sections we will justify the structure of the model and the variables we have taken into account.

A Comparison of the Variables Represented in the SH Model and the Simplified Model

In our model the structure and labels of the blocks are different from the SH model. A comparison of the blocks (see Table 1) illustrates that a high degree of coherence between the re-structured blocks and the SH model exists.

Nevertheless, there are some differences. First, we do not take into account variables representing the school organisation, etc. (SO) because of our sample. All students represented in our sample are enrolled in the same study programme at the same university. Therefore, all students are confronted with the same organisational circumstances and the same mathematics educator. In general, we suppose that these aspects influence the development of mathematical achievement. In lecturers’ and students’ perception, course design and organization influence study success (Anthony 2000). Aspects that should be considered for other samples are the kind of mathematics and the way mathematics is taught. According to Tall (2008), pure mathematics in university requires a transition from school mathematics to formal thinking. However, we do not focus on advanced mathematical thinking because B&E students learn maths as a service subject. Mathematics for economics has – to note one aspect – a strong focus on the application of mathematical methods and not on proofs. Second, we do not take into account most of the variables representing the home learning environment (HLE). We suppose that parental personalities, expectations, theories, support, climate and sanctions do not play such a big role in tertiary education, because university students are more independent than secondary school students. Only socio-economic variables that are measured by university degree of parents are supposed to influence achievement. Third, we do not take into account a separate block representing aspects of the cultural backgrounds of the students. Cultural background is represented by the variable migration background in block B. More aspects of cultural background would only be relevant within a broader sample with higher degree of diversity. Finally, we take several variables into account which cover study-specific aspects.

How to Operationalize the Blocks? First Remarks

Figure 4 lists the variables which are used to operationalize the six blocks. These blocks will serve as predictors for the students’ achievements in mathematics. After an elaboration of the methods and data in the next two sections, we will discuss in detail which variables should be included in the blocks by looking at theoretical arguments and relevant measurement issues.

Method

In this section we present the method we apply to estimate the determinants of maths performance at T1 (first week of the semester) and T2 (nine weeks later). In both cases we will apply the same linear regressions method. However, we have to take into account that at T1 and T2 different blocks of variables are relevant. Working habits (W t ) and the use of support services (U t ) refer to learning activities during the semester and are therefore not surveyed at T1. These blocks are relevant at T2. Moreover, at T2 previous knowledge has to be taken into account.

The following remarks might be helpful to understand the approach with respect to the use of data. The variables of block S and block B do not change from T1 to T2. Variables concerning motivational factors (block M) and learning strategies (block L) will change from T1 to T2. Variables of block W and block U are only relevant at T2. For that reason, variables belonging to the blocks S, B, M and L are surveyed at T1. At T2, the survey includes questions related to the blocks M, L, W and U.

Mathematical Representation

For the mathematical representation of the relationships we use the following notation:

- k :

-

index for students

- i :

-

index for variables within a block

- π T1 k :

-

maths performance of student k in T1

- π T2 k :

-

maths performance of student k in T2

- S ik :

-

k’s value for variable S i in T1 (and T2)

- B ik :

-

k’s value for variable B i in T1 (and T2)

- M ik :

-

k’s value for variable M i in T1, respectively T2

- L ik :

-

k’s value for variable L i in T1, respectively T2

- W ik :

-

k’s value for variable W i inT2

- U ik :

-

k’s value for variable U i in T2

- s, b, m, l, w, u :

-

number of variables included in block S, B, M, L, W, U

At the first point of time T1 (first week of the semester) we assume the following relationship in accordance with our model:

At the second point of time T2 (nine weeks after T1) we expect that also previous knowledge (measured by the knowledge at T1), working habits, as well as the use of voluntary support, will influence maths performance of students. As a consequence, we receive the following relationship:

Both models will be the theoretical basis for our empirical analysis.

Linear Regression Models

The starting points for our further analysis are Eqs. (1) and (2). In accordance with most studies in this research domain, we assume a linear relationship between student maths performance and the predictors motivated above. Scatterplots confirm the assumption of a linear relationship; see Figs. 5 and 6 (Appendix) as samples. This allows us to apply standard regression methods (e.g., Wooldridge 2015).

For T1 the following regression model will be analysed:

For T2 we have to add some more independent variables, as mentioned above:

In both Eqs. (3) and (4), the variables β j i represent canonically the regression coefficients which have to be estimated. The error terms are denoted by ε k . We use the standard ordinary least squares method to estimate the regression coefficients.

Nested Regression Methods

Nested regression methods are used where blocks of variables are taken into consideration. Every block of variables is successively integrated in the model if the determination coefficient R 2 increases significantly. For details see Acock (2014). Due to the structure of our model this regression method should be applied.

Data

General Setting

Data is drawn from two surveys which were carried out at University of Kassel in the winter semester 2011/12. At the beginning of the semester (T1, October 2011) students were asked to participate in a skills test and a questionnaire for the first time. The survey was completed in the first session of the lecture. The students were asked to participate in another skills test and questionnaire nine weeks later (T2, December 2011). In both cases, students had to complete the survey (skills test and questionnaire) in 75 min. All surveys were anonymous. Students were asked in both surveys to generate a unique password. This allows us to match data from T1 with data from T2.

The authors and one additional tutor managed the surveys. The surveys were voluntary. The skills tests were not part of the mark of the course, but they were used to give students feedback about their basic maths skills. There might be students who did not make much of an effort and could have performed better. However, we had the impression that most students took the survey seriously.

Participants

The sample consists of B&E students who were enrolled in the course ‘Mathematics for B&E students’ in the winter semester 2011/12. For most participants this course was compulsory. At time T1, 447 students participated in the survey; at time T2, 237students. Only 183 students participated in both surveys. Due to missing values for several variables the number of observations is smaller.

Skills Tests

Both skills tests used at T1 and, respectively, T2 include 30 tasks on fundamental mathematical topics which are taught at secondary schools. All tasks are solvable with secondary school mathematics and do not require specific economic knowledge. Table 2 gives an overview. With respect to the structure, the topics and the level of difficulty the two skills tests are comparable but they are not identical.

For each task, a student could obtain not more than one credit. The skills tests include different types of tasks: single choice tasks, multiple choice tasks, calculations and drawing graphs. The topics included in the skills tests are only briefly considered in lectures. However, voluntary support is provided for these topics.

Originally, the main purpose of the skills tests was to identify students with problems in basic mathematics skills in order to encourage them to use the voluntary support services provided. Therefore, tasks of the maths skills tests are structured by topics.

Questionnaires

At both points in time the students were asked to answer a questionnaire. At time T1, the students were asked questions which are related to the blocks of variables S, B, M, and L. The questionnaire consists of 16 questions and 47 Likert-type items. At time T2, in the middle of the semester, we also asked questions related to blocks W and U that included additional 44 Likert-type items. The questionnaires start with questions about study-specifics and biographic background. The Likert-type items are organized in blocks. The items are randomly scattered within these blocks.

Independent and Dependent Variables

In this section we will present and explain the variables which are subject of the empirical analysis. We start with the dependent variables π T1 and π T2. Afterwards, the variables of the six blocks will be discussed. This analysis is based on information presented in seven tables (Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9). All tables have the same structure: columns (1) to (3) contain the name of the variable, a brief description and comments. The type of the variable is presented in column (4). We take into account binary variables (yes / no or 1 / 0), metric variables (the values are real numbers) and scales. A scale is defined on the basis of two or more variables (items). For example, maths anxiety is based on three items. Column (5) presents the range of values a variable can show. Column (6) presents the number of items. If a variable is not defined as a scale, the value is 1. Due to the means of the variables at T1 and T2 (column (7) and column (9)) the reader will gain an impression of the magnitude of the variables and the change from T1 to T2. Moreover, for all scales Cronbach’s alpha (CA) is presented (column (8) and (10)) as a measure of reliability.

Dependent Variables: Mathematical Achievement in T1 and T2

As mentioned above, the skills tests provide two variables by generating sum scores, which we use as a measure for mathematics performance at T1 and T2, respectively:

- π T1 k :

-

maths performance of student k in T1

- π T2 k :

-

maths performance of student k in T2

Table 3 presents information about the two dependent variables. In particular, the table shows that mathematics performance improves over time.

Block S: Study-Specific Variables

With block S, we gather data about the students’ institutional study characteristics. The block consists of three variables (Table 4).

First, it is important to know whether the student has taken the preparation course in mathematics, which is offered just a few weeks before the test in T1 (variable S1). Like the test, this course is built on the maths curricula of secondary schools. For that reason the following results seem to be natural: if a student participated in the preparation course than we can expect a positive impact on maths performance. And, if a student who failed the final exam takes the main course twice (variable S2) than we conjecture that there is also a positive impact on the mathematical achievement. Finally, variable S3 represents the study programme a student has chosen. Most students are enrolled in the study programme ‘Business Administration & Economics’ (in German: Wirtschaftswissenschaften).

Block B: Socio-Economic and Biographic Variables

Block B of independent variables (Table 5) consists of important socio-economic and (educational) biographical variables that can also be found in well-known school performance studies like PISA or TIMSS.

Most of the eight variables are related to the educational background of the students. B2 indicates the type of school graduation. With respect to the complex German educational system, we distinguish between only two types of graduation: graduation from a ‘Fachoberschule’ ends with ‘Fachhochschulreife’ (FOS), graduation from a ‘Gymnasium’ with ‘Allgemeine Hochschulreife’ (Abitur). The tracks are quite different with respect to the number of school years (FOS: 12; Abitur 12 or 13) and the quantitative and qualitative workload in mathematics. For a description of the differences see EACEA (2015). Furthermore, we assume that the length of the period between the secondary school graduation and the start of higher education (B3) will have an impact on mathematical achievements. Faulkner et al. (2011) found that mature students who have not engaged in mathematics for a number of years (‘non-standard students’) are mathematically less prepared. Non-standard students perform below average in the diagnostic test at the beginning of the semester, but they improve and are more likely to use the voluntary support services. B6 und B7 represent the students’ success at school. We take the overall final grade and the final grade in mathematics into consideration.

Besides this, we consider four variables which are also present in many studies on secondary school achievement (e. g., PISA, TIMSS): gender (B1), migration background (B8) and the academic background of the parents (B4). Finally, B5 indicates that a student has completed an apprenticeship.

Block M: Motivational Factors

Block M, as part of the individual motivational determinants (IMD), includes six approved motivational scales (Table 6) that have been used for several studies (e. g. LIMA: Fischer et al. 2012; CO2CA: Bürgermeister et al. 2011; PISA: Kunter et al. 2002; PYTHAGORAS: Rakoczy et al. 2005). All scales are developed maths specific.

First, we include maths self-efficacy (M1) as a predictor for mathematical achievement. The concept of self-efficacy is based on a theoretical framework by Bandura (1977). “Perceived self-efficacy refers to beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments. […] Such beliefs influence the courses of action people choose to pursue, how much effort they put forth in given endeavors, how long they will persevere to adversity, whether their thought patterns are self-hindering or self-aiding, how much stress and depression they experience in coping with taxing environmental demands, and the level of accomplishments they realize” (Bandura 1997, p. 3). The scale is based on a common procedure applied e.g. by Pajares and Miller (1994). Just before the skills test, students rate for each task of the skills test how confident they are to solve the tasks.

Maths self-concept (M2), master goal orientation (M4) and maths anxiety (M5) are further scales. These scales are adopted from the German project LIMA (Fischer et al. 2012) that is concerned with creating new standards for the maths teachers’ education and implementing teaching innovations. Shavelson et al. (1976) define self-concept as a person’s perception of himself that can be described as “organized, multifaceted, hierarchical, stable, developmental, evaluative, differentiable” (p. 411). Based on the hierarchical model of self-concept we measure maths self-concept that is a subarea of the academic self-concept. Students rate e.g., how well they understand mathematical subjects and how gifted they are in mathematics. The distinction between self-efficacy and self-concept is difficult because the two constructs share a number of similarities. For a better distinction, we measure maths self-efficacy on a task-specific scale and maths self-concept on a domain specific scale. For a detailed review on the differences between the two constructs, see Bong and Skaalvik (2003).

The achievement goals construct is important in achievement motivation literature. Different conceptual models have been developed (Elliot et al. 2011, p. 632). The dichotomous model distinguishes between mastery goals and performance goals as purpose for engaging in achievement (Elliot et al. 2011, p. 632). Mastery goal orientations are “used to refer to goals that orient the individual to focus on the task in terms of mastering or learning how to do the task” (Pintrich 2000, p. 95). In contrast, performance goals are “goals that orient the individual to focus on the self, ability, or performance relative to others” (Pintrich 2000, p. 95). This model has been extended, for further information see Elliot et al. (2011). The meta-analysis of Huang (2011a) shows a weak positive correlation between mastery goal orientation and achievement and no correlation between performance goal orientation and achievement in the two-factor-model. Therefore, we only measure mastery goal orientation. A sample item is “I prefer challenging tasks, so I can learn a lot”.

Students with maths anxiety perceive mathematics-related situations as threatening to their self-esteem. The meta-analysis of Ma (1999) confirms the negative relation between maths anxiety and achievement in mathematics with an average correlation coefficient of -.27.

Maths interest (M3) is modelled in accordance with Rakoczy et al. (2005). According to Schiefele (2009) we measure individual interest that “is defined as a relatively stable set of valence beliefs” (p. 201). Interest focuses on the content of learning and “is always related to a specific object, activity, or subject area” (Schiefele 2009, p. 197). Therefore, we measure interest domain-specific, e.g. with “I find mathematics fascinating”.

We received a scale for the perceived value of maths (M6) by adaptation of a scale developed by Shell et al. (1989). Students were asked to rate the importance of mathematics for their study and career aspirations. Sample items are “How important are skills in mathematics to get a job?” and “How important are skills in mathematics to get good grades at university?”

Block L: Learning Strategies

Block L (Table 7) focuses on the learning strategies of the students. Capturing learning strategies is one way to measure aspects of self-regulated learning. The different models of self-regulated learning (e.g. the three-layer model by Boekaerts 1999) have the major components in common: cognitive, metacognitive and motivational components. Motivational aspects are captured in Block M. Cognitive and metacognitive components are a part of the individual cognitive determinants (ICD) that are operationalized by learning strategies. We expect that the type of learning strategies the students apply will influence the mathematical performance. Research indicates “the positive effect of students’ use of self-regulated learning strategies on their academic performance” (Zimmerman 1990, p. 185).

As in the case of motivational factors, we adopt scales that are applied in several studies on school achievement. Specifically, we define five scales representing the following learning strategies: memorising strategies (L1), elaboration strategies (L2) and control strategies (L3), planning strategies (L4), heuristic strategies (L5). While the scales L1 to L3 are based on scales used in LIMA and PISA, L4 and L5 are based on scales used in Rakoczy et al. (2005). The scales are domain-specific. The skills tests capture basic mathematical skills, not advanced mathematical thinking. Therefore, we apply scales that are originally used in studies on secondary school mathematics.

L1, L2 and L5 represent cognitive learning strategies; L3 and L4 represent metacognitive learning strategies. Sample items are: “To learn mathematics, I try to remember every step of the solution process” (L1), “When I am learning maths, I try to link the content with things I have already learned in other subjects.” (L2), “I ask myself questions about the content to be sure that I have understood everything.” (L3), “When I am learning maths, at first I plan what exactly I have to practise” (L4), “When I am solving a difficult task, I bring to my mind what is the main issue of the task.” (L5).

Cognitive strategies can be classified into surface cognitive and deep cognitive strategies. “Surface strategies refer to rehearsal, involving the repetitive rehearsal and rote memorization of information […]. Deep cognitive strategies, pertaining to elaboration, organization and critical thinking involve challenging the veracity of information encountered and attempting to integrate new information with prior knowledge and experience.” (Vrugt and Oort 2008, p. 128). Accordingly, L1 are surface cognitive strategies, L2 and L5 are deep cognitive strategies.

Empirical research supports a positive relationship between deep approaches of learning and achievement, and a negative relationship between surface approaches of learning and achievement (e.g. Ainley 1993). Other studies showed that a mix of surface and deep cognitive strategies is most effective (e.g. Vrugt and Oort 2008).

Block W: Working Habits

Block W (Table 8) consists of five variables which represent the working habits of the students.

In the questionnaire, the students were asked about their effort (W1), persistence (W2) and regularity (W3) regarding maths assignments. The fundamental idea of these variables is based on Rakoczy et al. (2005) and PISA. We adjusted the structure of the scales and the wording of the items. Sample items are “In mathematics I try to do everything as well as possible.” (W1), “I always endeavour to solve the assignments in mathematics.” (W2), “I do not give up even if the mathematical tasks are very difficult.” (W2) and “I work on the assignments every week as good as I can.” (W3). Furthermore, we asked the students how many hours they spent on the preparation of the lecture (W4) and the assignments (W5). Thus, the variables reflecting the students’ working habits are part of learning activities (LA). Obviously, these variables are only used as predictors for the explanation of the mathematical performance in T2. There is empirical support for this assumption (e.g. Kuh and Hu 1999; Strayhorn 2013).

Block U: Use of Support

Block U comprises variables that capture the use of (voluntary) support services. Besides the lecture, students can use a variety of voluntary support services. All services are offered every week throughout the semester. The variables included in block U (Table 9) show how often the students have used the services.

U1 shows how often the students participated in lectures (4 h per week). The mean of the variable is quite high. However, it should be mentioned that the questionnaire was conducted in the lecture at time T2.

The variables U2 to U7 are related to the voluntary support services.

-

U2: Tutorials (2 h per week, about 20 students per group) are voluntary courses; the tutors are experienced students (mostly third- and fourth-year students).

-

U3: Assignments are offered to the students every week. The solutions to the tasks of these assignments are discussed in the tutorials. The assignments are voluntary. In general, there is no individual feedback.

-

U4: Beside the assignments further tasks are offered. These tasks are not subject to the tutorials. There is no feedback.

-

U5: During the semester the students can visit the ‘MatheTreff’. This is an open learning environment. Four hours per week a seminar room is opened for students; a lecturer (PhD student or experienced student) is present who answers questions if required.

-

U6: Each week a voluntary test is offered. U6 shows the intensity of use of the tests with feedback. It means that the students submit solutions; after a week, the students receive written feedback. The reviewers are experienced students supervised by a lecturer (PhD student).

-

U7: This variable shows the intensity of use of the test without feedback. It means that students work on the test, but they do not submit solutions to the reviewers.

In general, we expect that the use of the support services will have positive impact on the mathematical performance. However, one aspect of the concept for the support services is crucial: While the skills tests take only tasks related to secondary school mathematics into account the support services cover the curriculum of the lecture for which secondary school mathematics plays only a limited role.

Results

Results for T1

First, we will present the results obtained for variables at T1 by determining correlation coefficients (see Table 14 in the Appendix). All motivational variables, except perceived value of maths (M6), correlate moderately with maths performance at T1. We find the strongest correlation with maths self-efficacy (M1) (r = .44). In addition, some study-specific and biographical background variables correlate moderately with maths performance. Exam already taken (S2) and type of graduation (B2) correlate positively and maths grade in school (B7) negatively with maths performance at T1. Learning strategies show a diverse pattern of correlations. Only elaboration strategies (L2) correlate positively, but weakly with maths performance. Control, planning and heuristic strategies (L3, L4, and L5) show no correlation with maths performance and memorising strategies (L1) even a weak negative correlation. All motivational variables correlate from moderately to strongly among themselves and with maths grade in school, but not strongly. Learning strategies correlate from moderately to strongly among themselves, too.

Second, we will present the results obtained for maths performance at T1 (π T1 k ) by applying block regression techniques. Every block of variables is successively integrated in the model if the determination coefficient R 2 increases significantly (tested with ANOVAs). For T1 four models are tested (M1a, M1b, M1c, M1d). All blocks of variables increased R 2 significantly (see Table 10). Study specific variables, socio-economic and biographic variables, motivational factors and learning strategies explain about half of the variance of maths performance at the beginning of the semester.

Detailed information on the four models with standardised regression coefficients for all integrated predictors is given in Table 11.

Most important in all three models are the participation of the maths preparation course (S1), having already taken the exam unsuccessfully (S2), the type of graduation (B2) and maths grade in school (B7). Coefficients of these variables decrease slightly when motivational variables are integrated (M1b); the influence of maths grade in school, especially, is decreasing. Maths self-efficacy and maths interest are significant predictors of maths performance in both models. The only significant coefficient for learning strategies in M1d we find for control strategies, but with a negative influence on maths performance.

Results for T2

All correlation coefficients of variables at T2 among themselves and with maths performance at T1 and T2 are presented in Table 14 (Appendix). Maths performance at T1 correlates very strong with maths performance at T2 (r = .80). These results are similar to results of correlational analysis of variables at T1. All motivational variables, except perceived value of maths, correlate from moderately to strongly with maths performance at T2. Type of graduation, elaboration and control strategies correlate moderately with maths performance at T2. Effort, persistence and regularity of working habits correlate moderately and positively with maths performance and strongly among each other. Hours spent for preparation show no correlation with maths performance and only weak correlations with other working habits. Use of assignments is the only variable of use of support that correlates moderately with maths performance.

The estimation procedure for applying block regression for maths performance in T2 does not differ substantially. However, pre-knowledge measured by maths performance at T1 and the variables related to the blocks W and U are now integrated. Table 12 shows the comparisons of seven models with a successive integration of blocks of variables. Maths performance at T1 explains over 60 % of the variance of maths performance at T2 (M2a). The integration of study specific variables leads to an increase of R 2, but not significantly.

Model M2c shows that the successive integration of socio-economic and biographic variables as well as the motivational variables (model M2d) raises R 2 significantly. The same holds for variables concerning working habits (model M2f). However, variables concerning learning strategies (model M2e) as well as variables representing the use of voluntary support (model M2g) do not increase R 2 significantly. The final model M2f explains about 75 % of the variance.

Detailed results for the models M2a, M2c, M2d and M2f with all variables are listed in Table 13. As mentioned above, maths performance in T1 is the most important predictor. Moreover, type and grade of graduation (B2, B6) are significant predictors. The only significant predictors of the motivational variables are maths anxiety (M5) and maths self-concept (M2, significant only in M2f). Working regularly on the weekly assignments and lectures (W3) is the most important predictor of working habits. As in the case of the estimates for T1 the matrix of correlation coefficients is inconspicuous. Multicollinearity does not occur.

Discussion

In this section we discuss the final estimates for model M1d for T1 and model M2f for T2 in more detail. It has to be stressed that the skills tests measure basic maths skills that are subject of secondary school mathematics. Tasks do not require advanced mathematical thinking. Therefore, applicability of the results of this study is limited. Aspects dealing with the nature and teaching of mathematics need to be added in the theoretical model in order to transfer it to achievement in pure mathematics.

Results for T1

At time T1, the maths skills of students are not influenced by the learning activities at the university. However, there are two exceptions. Some students participated in a preparation course before the semester started. Moreover, some participants did not pass the exam one semester earlier and had to repeat the module. In both cases we observe an expected positive influence. The regression coefficients for S1 and S2 are positive and significant at the 1 %-level. These results indicate that the preparation course helps students to refresh their basic maths skills, exactly as intended.

Students start their studies at university with very different educational backgrounds. In particular, the success depends on the type of graduation. Two types have to be distinguished in the case of the German educational system. The estimates show that students who have obtained an ‘Abitur’ achieve significantly better test results at time T1. The regression coefficient for B2 (‘Abitur’ = 1; ‘FOS’ = 0) is positive and significant.

Furthermore, it appears that better school grades also imply better performance at time T1. This holds for the grade in mathematics B7 (1 = excellent; 5 = insufficient) and the final grade B6 (1 = excellent; 5 = insufficient). These results about the influence of type of graduation and school grades are in accordance with the meta-analysis by Robbins et al. (2004) who identified ACT/SAT scores and high school GPA as the strongest predictors of college performance.

An academic background of the parents (B4) has a negative influence on the maths skills of students. This is a surprising result. Here, further analysis is necessary to find explanations.

Regarding gender (B1; male = 1, female = 0), the number of years between the end of secondary school and the start of the studies at the university (B3), apprenticeship (B5; yes = 1; no = 0) and migration background (B8; yes = 1; no = 0) we found no significant influence. The results for B3 and B5 do not support the results about non-standard students by Faulkner et al. (2011). Students who probably have not engaged in mathematics for some time (B3, B5) do not perform worse in the basic maths skills test at the beginning of the semester, but correlation analysis shows that on average they have worse final grades and maths grades, lower maths self-efficacy, lower maths self-concept and higher maths anxiety. One possible explanation might be that the influence of B3 and B5 is mediated by grades and motivational variables. Further analysis (e.g. with structural equation modelling) is needed.

The non-significant influence of migration background could be interpreted in a positive way. However, selection before starting university might be the reason.

Block M contains six variables representing motivational factors. Two of them show a significant influence. Maths self-efficacy has a positive influence (M3; low = 1; high = 8) on maths performance at T1 as well as maths interest M6 (low = 1; high = 6). Both results are compatible with findings from empirical studies on secondary schooling and higher education (see Multon et al. 1991; Laging 2016a). The other variables of this block (maths self-concept, mastery goal orientation, maths anxiety, perceived value of maths) have no significant influence in the multivariate regression analysis. The absolute values of these correlation coefficients of these variables with mathematics performance at T1 are between .20 and .39. But they also correlate moderately among each other and with maths self-efficacy and maths interest. This is consistent with the theoretical background. These constructs are distinct, but share several aspects. Especially self-efficacy and self-concept are similar concepts. Consequently, it is not surprising that they do not all show significant influence on maths performance in a multivariate approach. From a theoretical and empirical perspective it is not clear which of these variables is most important for performance. Many researchers (e.g., Bandura 1997; Pajares and Miller 1994; Zimmerman 2000) argue in favour of self-efficacy, because it is a more specific construct than self-concept. Our results for T1 support this conjecture.

Block L with a total of five variables reflects the learning strategies of students. Clearly, at time T1 the variables map the learning behaviour the students applied at school. Correlation analyses support the assumption of a positive relationship of deep cognitive strategies (elaboration) and basic maths skills, and a negative relationship of surface cognitive strategies (memorising) and basic maths skills. The correlation coefficients are small and multivariate analysis does not support these findings. Only the variable which represents control strategies has a statistically weak significant negative influence when applying multivariate regression techniques.

Comparing the estimated regression coefficients for the different models, it turns out that the inclusion of blocks does not have a major effect on magnitude and significance of the factors. But this is not unexpected, because the inclusion of blocks M and L increases R 2 only slightly.

In summary, it can be stated that in our study study-specific, biographical and motivational variables determine the mathematical success at T1 with the type of graduation as one of the most important factors. Students who start with ‘Abitur’ have attended the preparation course more frequently, are stronger interested in mathematics and have higher maths self-efficacy beliefs. Therefore, we have good and bad news. On the one hand, we can show that the use of voluntary support has a positive effect. On the other hand, the type of graduation remains of great importance.

Results for T2

The estimates for the final model M2f for T2 show similar results. Discussing the results, we have to keep in mind that the skills test at T2 covers the topics which were already relevant at T1. In both cases, all 30 tasks are related to secondary school maths. However, at T2 we expect better maths skills for a number of reasons. First, in a period of nine weeks between T1 and T2, students had the opportunity to refresh secondary school maths in self-study. Second, we expect that working habits (block W) and the use of support (block U) will have a positive influence on maths skills at T2 although secondary school maths plays only a minor role in lectures and voluntary support.

First, the pre-knowledge measured by π T1 is the most important factor influencing maths skills at T2. This factor explains about 60 % of the variance if only π T1 is taken into account as a predictor (see model M2a). The strong influence is not surprising, because the period between T1 and T2 is quite short and experience has shown that despite clear instructions, students underestimate the importance of basic mathematical skills. Therefore, many students spend only a very limited time and other resources in order to reduce deficits. The results for T1 show that maths skills at T1 are partly explained by several variables. As a consequence, π T1 is influenced by these variables. Further analyses, e.g. with structural equation modelling, which require a larger sample, are needed to separate the influences.

In the estimates for π T2 we find no evidence for an influence of study-specific effects. It is clear that the introduction of π T1 reduces the importance of the study-specific variables. As before, however, the B variables play an important role. Again, the type of graduation (B2; ‘FOS’ vs. ‘Abitur’) is crucial. Moreover, the final grade (B6) has a significant influence, but not the grade in maths.

The inclusion of the motivational variables leads to a significant increase of R 2. In general, it is the same as in the case of T1. But in detail, the results are different. Here, the factors maths concept (M2) and maths anxiety (M5) are significant at the 5 %-level. This underlines the assumption that it is not clear which factor influences maths performance the most, but in general self-belief is important.

The L block of variables representing learning strategies does not contribute to a significant increase of R 2. Correlation analyses show moderately positive correlations between elaboration strategies (L2) and control strategies (L3) with maths skills at T2. There is a moderately to high correlation of these strategies with motivational variables. These results indicate that the learning strategies we measured do not contribute for the explanation of maths skills at T2. The interpretation that learning strategies are not important for developing maths skills would be prejudged. There might be other reasons for these results. For example, it might be crucial how learning strategies are measured and which specific learning strategies are chosen. Measuring learning strategies by students’ ratings is problematic. Knowing specific strategies and applying these strategies are two different things. In addition, transition from school to university requires several changes including adjusting learning strategies. The scales we use to measure learning strategies might be inapplicable for this research. An examination of strategies students really need and use to acquire basic maths skills at university would be useful to adjust measurements of learning strategies.

The block of W-variables that represent the working behaviour of the students increases R 2 significantly. Only regularity (W3) shows a significant positive influence on maths skills in the multivariate approach. Correlation analyses show moderate correlations of effort, persistence and regularity with maths performance at T2, but no correlation of invested time and maths performance. Results of correlation analyses support research in the domain of homework. For example, results of multilevel modelling show that homework effort positively predicts maths achievement at the student level and time spent on homework has a negative influence on maths achievement (Dettmers et al. 2010). Spending much time on assignments can be a result of high effort, but also of lower cognitive abilities, missing knowledge, inappropriate learning strategies or missing concentration. Trautwein and Köller (2003) suggest distinctions between time spent on an assignment and time actively spent on it, and between time that is needed to complete an assignment and time actually spent on finishing it.

The use of various kinds of voluntary support does not contribute to a significant increase in R 2. At first glance, this is surprising. However, a substantial explanation may be that the voluntary support is only a limited form of assistance for the development of basic mathematical knowledge. Most of the voluntary support is substantially aligned with higher education mathematics, which covers most of the relevant topics of the module. Furthermore, many students did not use voluntary support in the winter semester 2011/12. One reason might be that most of the voluntary support services were established for the first time in that semester. Research on the use of voluntary support revealed that a small number of the students (especially students who have already taken the exam) uses the various kinds of support extensively, but most students use them rarely and irregularly (Laging and Voßkamp 2016).

To sum up, it can be stated that the mathematical skills at T2 are significantly influenced by pre-knowledge, the type of graduation, the school grade, maths self-concept and regular learning. Most of these variables represent students’ characteristics that are defined before they start their studies. This underpins the experience of students and maths educators that the negative effects of insufficient pre-knowledge and disadvantages due to educational background cannot be overcome in a short period. However, students whose working behaviour is characterised by regularity will show better results in maths performance.

Validity of the Models

It must be noted that the variables in M1d explain about 46 percent of variance in basic maths skills at T1, but still this model cannot explain a large proportion of variance. Consequently, factors have remained unconsidered or not sufficiently operationalised which are essential for the explanation of mathematical performance. Against this background, we cannot rule out that other variables mentioned in the model of SH may play an important role, e.g. home and school variables.

The variables in M2f explain about 74 % of variance in basic maths skills at T1. The inclusion of maths performance at T1 as an indicator for pre-knowledge increases R 2 substantially. A measure for pre-knowledge or cognitive ability to explain maths performance at T1 should be considered. At T1 pre-knowledge is measured by type of graduation and grades in school which are good predictors.

At both points of time, not all variables considered influence maths performance, which is not surprising by applying multivariate regression analyses. Individual cognitive and individual motivational determinants represented by a number of variables are confirmed as important predictors of maths performance. The weak support for learning activities as predictors might be due to the rare and irregular use of support services in this sample. Several variables do not show the assumed influence on maths performance as discussed above.

For our research, we adjusted the SH model to our sample. Therefore, several determinants need to be considered to transfer the model to other samples. Within a broad sample, variables measuring organization, climate and course context as well as cultural backgrounds should be added. In addition, the nature of mathematics and the way mathematics is instructed should be considered to capture specific issues of the transition of school mathematics to university mathematics.

Conclusion

Summary

In this paper, we have made an attempt to determine the predictors of mathematical skills of first-year B&E students. Based on data from skills tests and questionnaires, regression results have shown that for B&E students the type of graduation, the final school grade and maths grades in school are very important predictors of maths performance when they start their studies. Also, motivational variables contribute to the explanation of maths performance. Other socio-economic and biographical variables do not play a significant role. The same applies to the block of variables representing learning strategies. Moreover, the multivariate regression analysis shows that the maths skills in T1 representing pre-knowledge significantly influence the maths skills at T2.

Limitations

The results presented should be interpreted with reference to several limitations.

Sample: the sample includes only students of the University of Kassel. External validity is therefore limited. However, we have no indications that the results presented are driven by specific factors which would lead to biased results.

Measurement of mathematical achievements: the skills test covers different mathematical competencies (e. g., Blum et al. 2010), but not to the same extent (Laging 2016b). An analysis for specific domains of competencies is not possible due to the limited number of tasks. Moreover, we used classical test theory to construct the scales representing maths performance.

Measurement of the independent variables: the variables, respectively scales, related to the blocks M, L, W and U, have been created on the basis of proven and recognised concepts. However, it should be noted that the scales are based on self-assessments. Alternatives are not available in the framework of this approach.

Method: theoretical basis of the estimates is a simple model based on the concept of EPF. This simple model allows an empirical examination using regression techniques. Note, however, that the relevant theoretical contributions underpin strong arguments for the development of a path model or a structural equation model. In our case the number of observations is too small in order to test such models empirically.

Implications

Beside the limitations, our analyses show that a broad range of variables determines maths performance. For that reason, we can expect that numerous inventions exist which will have a positive impact on maths skills of first-year students. However, we can expect that an implementation of a single intervention will not cause a fundamental improvement of mathematics performance. Only a mix of interventions will work. In addition, it should be noted that many interventions cannot be implemented by the maths educators or the students. Universities are faced to many factors they cannot control. In particular, this applies to factors which we take in the blocks S and B into account. For example, (German) universities have only limited options to define criteria for admission which affect the composition of the cohorts of the first-year-students.

Despite these general remarks, from the perspective of lecturers and students our analyses justify at least two concrete recommendations. First, our results show that voluntary support can have a significant positive impact on maths performance. In our case, this prevails especially for a preparation course. Second, our results show that regular learning is of great advantage. The positive influence of regularity brings up the question how incentives or command and control can force regularity. Further exams and weekly compulsory assignments might be appropriate inventions.

Outlook

The results presented are a first step towards the explanation of mathematical skills of first-year students. However, the identified limitations leave scope for further studies that can be done only within the framework of a larger project.

An extension of the database by the inclusion of students at other universities is desirable. This could in particular contribute to the external validity of the results.

The mathematical skills of students were measured using classical test theory. In a further step the variables representing maths performance could be calculated in line with item response theory (IRT). However, we do not expect significant changes of the results.

The explanatory variables have been formulated on the basis of the questionnaires. The associated problems were mentioned. Using alternative methods would improve the analysis. For example, learning diaries offer better opportunities to capture the way students learn and work. However, this would go beyond the scope of this project.

Finally, from a theoretical point of view an investigation of indirect effects of the observed variables is desirable. This would drive the analyses towards structural equation modelling. However, such a research strategy is only meaningful if the analysis is not limited by the availability of data.

References

Acock, A. C. (2014). A gentle introduction to stata (4th ed.). College Station: Stata Press.

Ainley, M. D. (1993). Styles of engagement with learning: multidimensional assessment of their relationship with strategy use and school achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 395–405.

Anderson, G., Benjamin, D., & Fuss, M. A. (1994). The determinants of success in university introductory economics courses. The Journal of Economic Education, 25(2), 99–119.

Anthony, G. (2000). Factors influencing first-year students’ success in mathematics. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 31(1), 3–14.

Arnold, I. J. M., & Straten, J. T. (2012). Motivation and math skills as determinants of first-year performance in economics. The Journal of Economic Education, 43(1), 33–47.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy. The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Bausch, I., Biehler, R., Bruder, R., Fischer, P. R., Hochmuth, R., Koepf, W., Schreiber, W., & Wassong, T. (Eds.). (2014). Mathematische Vor- und Brückenkurse: Konzepte, Probleme und Perspektiven (Mathematical preparatory and bridging courses: concepts, problems and perspectives). Heidelberg: Springer.

Blanchard, O., & Johnson, D. R. (2012). Macroeconomics. Boston: Pearson.

Blum, W., Drüke-Noe, C., Hartung, R., & Köller, O. (Eds.). (2010). Bildungsstandards Mathematik. (Educational standards). Berlin: Cornelsen.

Boekaerts, M. (1999). Self-regulated learning: where we are today. International Journal of Educational Research, 31, 445–457.

Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: how different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 15(1), 1–40.

Brewer, D. J., Hentschke, G. C., & Eide, E. R. (2010). Theoretical concepts in the economics of education. In D. J. Brewer & P. J. McEwan (Eds.), Economics of education (pp. 3–8). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bürgermeister, A., Kampa, M., Rakoczy, K., Harks, B., Besser, M., Klieme, E., Blum, W. & Leiß, D. (2011). Dokumentation der Befragungsinstrumente des Laborexperimentes im Projekt ‘Conditions and Consequences of Classroom Assessment (Co 2 CA)’ (Documentation of the survey instruments of the laboratory experiment in the project ‘Conditions and Consequences of Classroom Assessment (Co 2 CA)’). Frankfurt am Main: DIPF.

Chemers, M. M., Hu, L., & Garcia, B. F. (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first-year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 55–64.

Chiang, A. C., & Wainwright, K. (2005). Fundamental methods of mathematical economics (4th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Chiu, M. M., & Xihua, Z. (2008). Family and motivation effects on mathematics achievement: analyses of students in 41 countries. Learning and Instruction, 18, 321–336.

Clark, M., & Lovric, M. (2008). Suggestion for a theoretical model for secondary-tertiary transition in mathematics. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 20(2), 25–37.

Demir, I., Kilic, S., & Depren, Ö. (2009). Factors affecting Turkish students’ achievement in mathematics. US-China Education Review, 6(6), 47–53.

Dettmers, S., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Kunter, M., & Baumert, J. (2010). Homework works if homework quality is high: using multilevel modeling to predict the development of achievement in mathematics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2), 467–482.

EACEA (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency) (2015). Description of national education systems. Germany. Resource document. https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/fpfis/mwikis/eurydice/index.php/Germany:Redirect.

Elliot, A. J., Murayama, K., & Pekrun, R. (2011). A 3 X 2 Achievement goal model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 632–648.

Eurostat (2013). European systems of accounts. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Faulkner, F., Hannigan, A., & Gill, O. (2011). The changing profile of third level service mathematics in Ireland and its implications for the provision of mathematics education (1998–2010). In M. Pytlak, T. Rowland, & E. Swoboda (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th Conference of European Researchers in Mathematics Education (pp. 1992–2001). Rzeszow, Poland.

Fischer, E., Bianchy, B., Biehler, R., Hänze, M. & Hochmuth, R. (2012). Lehrinnovationen in der Studieneingangsphase ‘Mathematik im Lehramtsstudium’. Hochschuldidaktische Grundlagen, Implementierung und Evaluation. Skalendokumentation (Teaching innovations in the first study phase ‘Mathematics in teacher training programmes’. Fundamentals, implementation and evaluation. Scales documentation). Unpublished.

Gueudet, G. (2008). Investigating the secondary-tertiary transition. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 67, 237–254.

Hailikari, T., Nevgi, A., & Komulainen, E. (2008). Academic self-beliefs and prior knowledge of student achievement in mathematics: a structural model. Educational Psychology, 28(1), 59–71.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Abingdon: Routledge.

Helmke, A., & Weinert, F. E. (1997). Bindungsfaktoren schulischer Leistungen (Factors of school achievement). In F. E. Weinert (Ed.), Enzyklopädie der Psychologie, Band 3 (Psychologie der Schule und des Unterrichts) (pp.71–176). Göttingen Hogrefe-Verlag.

Heublein, U. (2014). Student drop-out from German education institutions. European Journal of Education, 49(4), 497–513.

Hoppenbrock, A., Biehler, R., Hochmuth, R., & Rück, H.-G. (Eds.). (2016). Lehren und Lernen von Mathematik in der Studieneingangsphase (Teaching and learning of mathematics in the first study phase). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Huang, C. (2011). Achievement goals and achievement emotions: a meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 23(3), 359–388.

Klieme, E. (2006). Empirische Unterrichtsforschung: Aktuelle Entwicklungen, theoretische Grundlagen und fachspezifische Befunde. Einleitung in den Thementeil (Empirical classroom research: current developments, theoretical background and specialist results). Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 52(6), 765–773.

Kuh, G. D., & Hu, S. (1999). Unraveling the complexity of the increase in college grades from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 21(3), 297–320.

Kunter, M., Schümer, G., Artelt, C., Baumert, J., Klieme, E., Neubrand, M., Prenzel, M., Schiefele, U., Schneider, W., Stanat, P., Tillmann, K.-J., & Weiß, M. (2002). PISA 2000: Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente (PISA 2000. Documentation of survey instruments). Materialien aus der Bildungsforschung Nr. 72.. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institut für Bildungsforschung.

Laging, A. (2016a). A meta-analysis about the relation of self-efficacy beliefs and achievement in mathematics. In preparation.

Laging, A. (2016b). Stärke und Exaktheit der mathematischen Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen bei Studienanfänger/innen (Strength and accuracy of first-year students’ mathematical self-efficacy). In preparation.

Laging, A., & Voßkamp, R. (2016). Identifizierung von Nutzertypen bei fakultativen Angeboten zur Mathematik in wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Studiengängen (Identification of user types in the case of voluntary support services to mathematics in economics courses). In A. Hoppenbrock, R. Biehler, R. Hochmuth, & H.-G. Rück (Eds.), Lehren und Lernen von Mathematik in der Studieneingangsphase (pp. 585–600). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Liston, M., & O’Donoghue, J. (2009). Factors influencing the transition to university service mathematics: part I a quantitative study. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications, 28, 77–87.

Ma, X. (1999). A meta-analysis of the relationship between anxiety towards mathematics and achievement in mathematics. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 30(5), 520–540.

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: a meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(1), 30–38.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2003). Literacy skills for the world of tomorrow: Further results from PISA 2000. Paris: OECD

Pajares, F., & Miller, D. (1994). Role of self-efficacy and self-concept beliefs in mathematical problem solving. A path analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(2), 193–203.