Abstract

It is urgent to solve the problems of the dramatic volume expansion and pulverization of SnO2 anodes during cycling process in battery systems. To address this issue, we design a hybrid structure of N-doped carbon fibers@SnO2 nanoflowers (NC@SnO2) to overcome it in this work. The hybrid NC@SnO2 is synthesized through the hydrothermal growth of SnO2 nanoflowers on the surface of N-doped carbon fibers obtained by electrospinning. The NC is introduced not only to provide a support framework in guiding the growth of the SnO2 nanoflowers and prevent the flower-like structures from agglomeration, but also serve as a conductive network to accelerate electronic transmission along one-dimensional structure effectively. When the hybrid NC@SnO2 was served as anode, it exhibits a high discharge capacity of 750 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1 after 100 cycles in Li-ion battery and 270 mAh g−1 at 100 mA g−1 for 100 cycles in Na-ion battery, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Highlights

-

A hybrid structure of SnO2 nanoflowers grown on N-doped carbon nanofibers (NC@SnO2) was successfully constructed.

-

N-doped carbon nanofiber accelerates the migration of Li+/Na+ ions and guides the growth of the SnO2 nanoflowers.

-

NC@SnO2 electrode reveals excellent energy storage performance for Li- and Na-ion batteries.

2 Introduction

With severe resource constraints and global environmental problems, it is necessary to develop highly efficient energy storage systems to reduce the use of fossil fuels [1,2,3,4,5]. Nowadays, lithium- and sodium-ion batteries (LIBs and SIBs) have attracted widespread attention all over the world [6,7,8]. LIBs have been extensively applied in portable electronic equipment and electric vehicles (EVs) and intelligent power grids because of their outstanding characteristics of high energy density, no memory effect, and small self-discharge [9, 10]. Recently, owing to the lack of lithium resources and the similar chemical property of Na+ to Li+, SIBs have also received increasing attention [11, 12]. As one of the important parts for LIBs or SIBs, the high-performance electrode materials are urgently needed for next-generation battery systems.

As one of the typical transition-metal oxides (TMOs), tin dioxide (SnO2) is widely concerned to be promising electrode materials owing to its non-toxicity, low cost, high theoretical capacity, and outstanding electrochemical performance [13,14,15]. Nevertheless, it is similar to the shortcomings of other oxide materials during cycling processes that SnO2 endures the dramatic volume change. This would lead to the capacity decay and poor cycling performance [16,17,18]. To improve the electrochemical performance of SnO2, nanostructured SnO2 is employed to reduce the volume variation of SnO2 during the charge/discharge process [19,20,21]. However, it is easily agglomerated for nanostructured SnO2 to reduce the specific surface area of the active materials, leading to the attenuation of energy storage. To overcome this problem, a great deal of SnO2/carbon composites has been designed to maintain the structural stability of electrodes and improve the electrical conductivity of composites [22,23,24]. In addition, the N-doped carbon composite materials are considered to enhance the electrical conductivity and accelerate the reaction speed of the SnO2 composites, and increase defect sites for the efficient storage of lithium/sodium ions [25,26,27].

In this work, we synthesized a hybrid structure of N-doped carbon fibers@SnO2 nanoflowers (NC@SnO2) by electrospinning/hydrothermal methods. When they are used as an anode material in LIBs and SIBs, the as-prepared NC@SnO2 hybrid material displayed excellent electrochemical properties. The high discharge capacity reached 750 mAh g−1 at a current density of 1 A g−1 after 100 cycles in LIBs. Meanwhile, a reversible discharge capacity of 270 mAh g−1 was achieved at a current density of 100 mA g−1 after 100 cycles in SIBs.

3 Experimental Section

3.1 Synthesis of SnO2, N-doped Carbon, and NC@SnO2

All chemical reagents were purchased and used without further treatment. The synthesis of SnO2 nanoflowers was carried out according to the previous literature [28]. The N-doped carbon (NC) nanofibers were synthesized by electrospinning as follows: 0.6 g polyacrylonitrile (PAN, Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd. USA) was firstly added into 7 g N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China). Then, the above solution was poured into 10-mL plastic syringe and followed by electrospinning. The NC nanofibers were finally obtained via annealing the precursor at 600 °C in Ar atmosphere. To synthesize NC@SnO2, 4 mmol tin(II) chloride dihydrate (SnCl2·2H2O, Xilong Chemical Co., Ltd., China) and 8 mmol sodium citrate (Na3C6H5O72·H2O, Tianjin Hengxing Chemical Reagent Manufacturing Co., Ltd., China) were firstly dissolved into the mixed solvent of 15 mL ethanol and 15 mL water. After stirring for 30 min, 80 mg NC nanofibers were introduced into the above blend solution. Subsequently, the mixture solution was put into a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave at 180 °C for 12 h after continuous ultrasound for 30 min. The precursor samples were taken out the autoclave after the end of the reaction and ultrasonic cleaning with deionized water and ethanol. Finally, the NC@SnO2 samples were obtained with annealing at 500 °C for 3 h in Ar gas.

3.2 Material Characterizations

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) of the samples was conducted with a Shimadzu XRD-6000 instrument, and the morphologies and structural features of the samples were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S4800) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEOL 2010 with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV). The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the powder sample was surveyed with a WCT-1D instrument (BOIF, China) in air atmosphere from 30 to 800 °C. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) of the sample was performed with the adsorption of N2 with a nova 2000 e volumetric adsorption analyzer (Kangta, USA), The element composition and chemical bonds of the sample were detected by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific Escalab 250Xi, USA). Raman spectra of the samples were conducted by utilizing micro-Raman spectrometer (LabRAM HR Evolution, HORIBA).

3.3 Electrochemical Measurements

The working electrodes of LIBs and SIBs were fabricated by using 80 wt% of active materials (NC@SnO2, SnO2, and NC), 10 wt% of acetylene black, and 10 wt% of carboxymethylcellulose sodium (CMC). The mixture was uniformly distributed in the deionized water and ethanol and coated on the copper foil which dried at 60 °C in a vacuum drying oven for a day. CR2025-type coin half-batteries of as-prepared electrodes were assembled in the glove box with water and oxygen content of less than 0.5 ppm. The microporous polypropylene (Celgard 2400) and glass microfiber filter membranes (Whatman, Grade GF/A) were utilized as a separator of LIBs and SIBs, respectively. And corresponding metal plates were used as the counter electrodes of batteries. The electrolyte of LIBs was composed of 1.0 M of LiPF6 solution which mixed ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC) with 1:1 in volume, and the electrolyte of SIBs was constituted by 1.0 M of NaClO4 solution which mixed EC with DMC (1:1 in volume), accompanied with 5% fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) of additive agent. The electrochemical property and cyclic voltammetry measurement of LIBs and SIBs were performed with Neware Battery Testing System and CHI 660C Electrochemical Workstation, respectively.

4 Results and Discussion

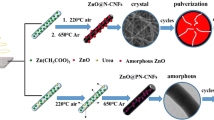

The synthetic process of NC@SnO2 is schematically shown in Fig. 1. Firstly, NC nanofibers were synthesized by the electrospinning method using PAN as the precursor, followed by heat treatment. Subsequently, SnO2 nanoflowers were grown on the NC nanofibers by hydrothermal method. The morphology and structures of the samples were characterized by SEM and TEM, as displayed in Fig. 2. Figure 2a, b displays that SnO2 sample is composed of agglomerated nanoflowers, which are assembled by nanosheets. When the NC nanofibers (Fig. S1) are introduced and used as the core for the hybrid structure, the SnO2 nanoflowers could grow on the surface of NC nanofibers, as shown in SEM images (Fig. 2c, d). Compared to SnO2 nanoflowers, the NC@SnO2 composite materials are formed by thinner nanosheets and better dispersed. In addition, the TEM image (Fig. 2e) of NC@SnO2 further indicates that one fiber is completely covered with the thin nanosheets. The high-resolution TEM image (Fig. 2f) indicates that the SnO2 nanosheet is well crystalline and has a lattice plane (110) with a crystal lattice distance of 0.338 nm.

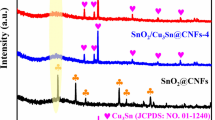

The crystal structures of NC@SnO2, SnO2, and NC materials were analyzed by XRD. From Fig. 3, one can observe that the diffraction peaks of NC@SnO2 and SnO2 are well consistent with the standard card (JCPDS card No. 21-1250), and the 2θ values of main peaks centered at 26.58, 33.88, 37.95, 51.75, and 54.76 are corresponded to the lattice planes of tetragonal SnO2 (110), (101), (200), (211), and (220), respectively. The diffraction peaks of NC are in accordance with the standard card (JCPDS card No. 3-401), and the 2θ values 26.60 and 54.79 are corresponded to the lattice planes of hexagonal carbon (006) and (0012), respectively. Nevertheless, the peak of carbon for the NC@SnO2 is not clearly observed. It is possible that the NC nanofibers were completely covered by the SnO2 nanoflowers, which make the carbon peaks disappear in NC@SnO2. The Raman spectrum of NC@SnO2 (Fig. S2) indicates that the two peaks at ~ 1350 and 1580 cm−1 are corresponded to the D peak of disorder carbon and the G peak of graphitic carbon. The relative intensity (I D/I G ≈ 1.397 > 1) indicates that there exist mass defects caused by the N-doping in NC@SnO2 [29,30,31]. Additionally, the TGA curve of NC@SnO2 (Fig. S3) indicates that the lost weight of the sample appears in the range of 400–800 °C and the weight retention of SnO2 is confirmed to be about 67.81%.

The BET was utilized to confirm the surface information of the materials. Figure S4a, b shows the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of NC@SnO2 and SnO2 materials. The surface areas of NC@SnO2 and SnO2 are 45.59 and 37.01 cm3 g−1, respectively. Meanwhile, the pore-size distribution curves (Figs. S4c, d) indicate that the NC@SnO2 and SnO2 have the average pores of 3.74 and 2.56 nm, respectively. The larger specific surface area and pore size of NC@SnO2 are beneficial to the storage and transport of lithium/sodium ions. Moreover, the chemical component and surface electronic states of the NC@SnO2 material were further surveyed by XPS, and all peaks of these elements Sn, O, N, and C are observed as shown in Fig. S5 [32]. The high-resolution spectra of Sn 3d, O 1s, N 1s, and C 1s were recorded as shown in Fig. 4. The peaks of the Sn 1s (Fig. 4a) could be resolved into 486.78 and 495.12 eV, which are assigned to the binding energies of Sn 3d5/2 and Sn 3d3/2 of SnO2 [33]. The peaks of the O 1s (Fig. 4b) can be divided into two peaks of 530.61 and 531.36 eV and corresponded to Sn–O and C=O, respectively [34, 35]. The signal of N 1s could be obviously divided into two peaks of 398.00 and 399.76 eV (Fig. 4c), which well accorded with the binding energies of pyridinic N and pyrrolic N [36], it is verified the existence of nitrogen in NC@SnO2. Additionally, the peaks of the C 1s (Fig. 4d) could be resolved into three binding energies. The peak located at 285.89 eV corresponding to C–N bond can further confirm the presence of nitrogen in NC@SnO2 [37], and the other peaks of 284.42 and 288.54 eV are accorded with the binding energies of C–C and C=O, respectively [38].

The NC@SnO2 was investigated as anode material for LIBs. SnO2 and NC nanofiber were also conducted for comparison. The CV curves of NC@SnO2 between 0.001 and 3.0 V vs Li+/Li at scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1 are shown in Fig. 5a, and it can be observed that there exists a subtle distinction in the first three cycles. The reduction peaks are found at the scope of 1.5–1.8 and 0.5–1.0 V at the first curve. They are attributed to the conversion process from SnO2 to Sn (Eq. 1) and the formation of SEI films, respectively [39, 40]. The peak below 0.5 V is associated with the lithiation (LixSn) of Sn (Eq. 2) [41]. In the following two CV curves, the reduction peaks at about 1.2, 0.8, and 0.3 V are associated with the reversible conversion reaction of SnO2 and alloy–dealloy reaction of Sn [42]. The oxidation peaks of about 0.8, 1.2 V and the small oxidation peak of 2.1 V are derived from the delithiation reaction of LixSn (Eq. 3) and reversible changing reaction of Sn between SnO and SnO2 (Eq. 4), respectively [42]. The Li+ de/intercalation of conversion process is described as follows,

The charge/discharge profiles of NC@SnO2 at the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 5th cycle were displayed at in Fig. 5b. The voltage platforms of charge–discharge can be observed to be consistent with the oxidation–reduction peaks of above CV curves. The initial discharge–charge capacities of NC@SnO2 are 1463.6 and 1009.8 mAh g−1, respectively. And the low initial coulombic efficiency of 67.0% may be associated with the formation of SEI film and the irreversible reactions of SnO2 material in the first cycle [32, 43]. The cycling performance of NC@SnO2, SnO2, and NC is shown in Fig. 5c. The discharge capacity of NC@SnO2 is about 750 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1 after 100 cycles, while the discharge capacities of SnO2 and NC only remain 480 and 220 mAh g−1, respectively. In Fig. 5d, one can see that the average capacities of NC@SnO2 are about 1100, 850, 763, 684, 615, 568, and 905 mAh g−1 at different current densities of 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 0.2 A g−1, respectively. However, the average capacities of SnO2 are only about 966, 842, 765, 685, 525, 370, and 770 mAh g−1 at 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 0.2 A g−1, respectively. And the NC electrode exhibits the capacities less than 550 mAh g−1 at various current densities.

The electrochemical property of NC@SnO2 was further investigated in SIBs. Figure 6a displays the CV curves of NC@SnO2 in the voltage range from 0.001 to 3.0 V vs Na+/Na at scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1. The obvious slope of 0.5–1.0 V is ascribed to the generation of the SEI film and the irreversible reactions between SnO2 with sodium ions to generate NaxSn alloys in the first cycle [22]. In the initial three cycles, the two reduction peaks at about 1.0 and 0.3 V correspond to the insertion of sodium ions with the formation of Sn and NaxSn, respectively. And the oxidation peak at 1.25 V corresponds to the de-intercalation of sodium ions [44, 45]. The reversible reaction of SnO2 with sodium ions to the production of Na2O and NaxSn in the charge–discharge process can be represented as follows [44],

Figure 6b displays the discharge/charge capacities of 555.7/212.5 mAh g−1 in the first charge/discharge cycle, respectively, with a coulombic efficiency of 38.2%. The low coulombic efficiency can be attributed to the formation of SEI film, and the irreversible reaction of SnO2 with sodium ion to form NaxSn alloys in the first discharge process [46, 47]. In this work, the SnO2 and NC electrodes are used as a reference. In Fig. 6c, one can see that the discharge capacity of NC@SnO2 is about 270 mAh g−1, compared with 55 and 220 mAh g−1 of SnO2 and NC at 100 mA g−1 after 100 cycles. The rate performances for the three electrodes were also studied as shown in Fig. 6d. When the current densities were set at 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1, and 0.1 A g−1, the NC@SnO2 electrode exhibits the discharge capacities of about 295, 300, 280, 247, 202, 193, and 300 mAh g−1, respectively. These results are better than those of SnO2 and NC electrodes.

To further demonstrate the structural stability of hybrid NC@SnO2, the SEM images of electrodes after about 75 cycles are given in Figs. 7 and S6. The SEM images of NC@SnO2 and SnO2 electrodes as anode for LIBs after cycling are shown in Fig. 7. Compared to the SEM images of the SnO2 electrodes (Fig. 7c, d), we can observe the obvious NC could be retained, and the SnO2 nanoflowers are not completely collapsed as shown in Fig. 7a, b. It demonstrates that the hybrid NC@SnO2 electrodes have the better cycle performance and rate capability than those of SnO2 electrodes in the LIBs due to the more stable structure of hybrid NC@SnO2 material. We also investigated the structural change of both NC@SnO2 and SnO2 electrodes for SIBs. As shown in the SEM images of NC@SnO2 electrode after cycling (Fig. S6a), the network structure of the NC could still be observed and no obvious reunion in comparison with the SnO2 electrode (Fig. S6c). However, SnO2 nanoflowers are completely collapsed in both NC@SnO2 and SnO2 electrodes, as shown in the high-magnification SEM images (Fig. S6b, d). This is because that the formation of Na–Sn alloy with enormous volume changes makes the pulverization of SnO2 material upon repetitive cycling [20]. These results indicated that NC nanofibers of the NC@SnO2 electrode can not only provide a conductive network, but also prevent the aggregation and pulverization of the SnO2 nanoflowers during the charge and discharge process.

5 Conclusion

In summary, we have successfully prepared a hybrid structure of NC@SnO2 by electrospinning/hydrothermal methods. The NC nanofibers of the hybrid NC@SnO2 can prevent the agglomeration of SnO2 nanoflowers and effectively accelerate the transition of Li+/Na+ ion to promote the rate capability. Moreover, the structure can make more surface of the nanoflower exposed and buffer the volume expansion of SnO2 to enhance discharge capacity and cycling performance during cycling process. In addition, the hybrid NC@SnO2 could deliver a discharge capacity of 750 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles at 1 A g−1 for Li-ion battery and 270 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles at 100 mA g−1 for Na-ion battery.

References

J. Xu, J. Ma, Q. Fan, S. Guo, S. Dou, Recent progress in the design of advanced cathode materials and battery models for high-performance lithium-X (X=O2, S, Se, Te, I2, Br 2) batteries. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606454 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201606454

C. Cui, J. Xu, L. Wang, D. Guo, M. Mao, J. Ma, T. Wang, Growth of NiCo2O4@MnMoO4 nanocolumn arrays with superior pseudocapacitor properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8(13), 8568–8575 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b02962

D. Guo, L. Lai, A. Cao, H. Liu, S. Dou, J. Ma, Nanoarrays: design, preparation and supercapacitor applications. RSC Adv. 5(69), 55856–55869 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA09453D

F. Mao, W. Guo, J. Ma, Research progress on design strategies, synthesis and performance of LiMn2O4-based cathodes. RSC Adv. 5(127), 105248–105258 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA21777F

J. Xu, Y. Dou, Z. Wei, J. Ma, Y. Deng, Y. Li, H. Liu, S. Dou, Recent progress in graphite intercalation compounds for rechargeable metal (Li, Na, K, Al)-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 4(10), 1700146 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201700146

L. Wang, B. Ruan, J. Xu, H.K. Liu, J. Ma, Amorphous carbon layer contributing Li storage capacity to Nb2O5@C nanosheets. RSC Adv. 5(45), 36104–36107 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA05935F

Y. Cai, J. Ma, T. Wang, Hydrothermal synthesis of α-Ni(OH)2 and its conversion to NiO with electrochemical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 582, 328–333 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.07.206

C. Cui, X. Li, Z. Hu, J. Xu, H. Liu, J. Ma, Growth of MoS2@C nanobowls as a lithium-ion battery anode material. RSC Adv. 5(112), 92506–92514 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA17992K

V. Etacheri, R. Marom, R. Elazari, G. Salitra, D. Aurbach, Challenges in the development of advanced Li-ion batteries: a review. Energy Environ. Sci. 4(9), 3243–3262 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1039/c1ee01598b

P. Roy, S.K. Srivastava, Nanostructured anode materials for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(6), 2454–2484 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA04980B

L. Wang, Y.-G. Sun, L.-L. Hu, J.-Y. Piao, J. Guo, A. Manthiram, J. Ma, A.-M. Cao, Copper-substituted Na0.67Ni0.3-xCuxMn0.7O2 cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries with suppressed P2-O2 phase transition. J. Mater. Chem. A 5(18), 8752–8761 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TA00880E

V. Palomares, P. Serras, I. Villaluenga, K.B. Hueso, J. Carretero-Gonzalez, T. Rojo, Na-ion batteries, recent advances and present challenges to become low cost energy storage systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 5(3), 5884–5901 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ee02781j

Y. Chen, J. Ma, Q. Li, T. Wang, Gram-scale synthesis of ultrasmall SnO2 nanocrystals with an excellent electrochemical performance. Nanoscale 5(8), 3262–3265 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3nr00356f

S.J.R. Prabakar, Y.-H. Hwang, E.-G. Bae, S. Shim, D. Kim, M.S. Lah, K.-S. Sohn, M. Pyo, SnO2/graphene composites with self-assembled alternating oxide and amine layers for high Li-storage and excellent stability. Adv. Mater. 25(24), 3307–3312 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201301264

J. Deng, Y. Chen, J. Ma, E. Zhang, T. Wang, Solvothermal synthesis of hollow urchin-like SnO2 nanospheres with superior lithium storage behavior. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 13(6), 4297–4301 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2013.7181

F. Yan, X. Tang, Y. Wei, L. Chen, G. Cao, M. Zhang, T. Wang, Stannous ions reducing graphene oxide at room temperature to produce SnOx-porous, carbon-nanofiber flexible mats as binder-free anodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(24), 12672–12679 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5TA02107C

Y. Zhao, C. Wei, S. Sun, L.P. Wang, Z.J. Xu, Reserving interior void space for volume change accommodation: an example of cable-like mwnts@ SnO2@C composite for superior lithium and sodium storage. Adv. Sci. 2(6), 1500097 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201500097

C. Guan, X. Wang, Q. Zhang, Z. Fan, H. Zhang, H.J. Fan, Highly stable and reversible lithium storage in SnO2 nanowires surface coated with a uniform hollow shell by atomic layer deposition. Nano Lett. 14(8), 4852–4858 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/nl502192p

X.M. Yin, C.C. Li, M. Zhang, Q.Y. Hao, S. Liu, L.B. Chen, T.H. Wang, One-step synthesis of hierarchical SnO2 hollow nanostructures via self-assembly for high power lithium ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 114(17), 8084–8088 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp100224x

L. Chen, X. Yin, L. Mei, C. Li, D. Lei et al., Mesoporous SnO2@carbon core-shell nanostructures with superior electrochemical performance for lithium ion batteries. Nanotechnology 23(3), 035402 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/23/3/035402

L. Fan, X. Li, B. Yan, J. Feng, D. Xiong et al., Controlled SnO2 crystallinity effectively dominating sodium storage performance. Adv. Energy Mater. 6(10), 1502057 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201502057

M. Dirican, Y. Lu, Y. Ge, O. Yildiz, X. Zhang, Carbon-confined SnO2-electrodeposited porous carbon nanofiber composite as high-capacity sodium-ion battery anode material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 7(33), 18387–18396 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b04338

B. Huang, X. Li, Y. Pei, S. Li, X. Cao, R.C. Massé, G. Cao, Novel carbon-encapsulated porous SnO2 anode for lithium-ion batteries with much improved cyclic stability. Small 12(14), 1945–1955 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201503419

J. Xu, G. Jia, W. Mai, H.J. Fan, Energy storage performance enhancement by surface engineering of electrode materials. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 3(20), 1600430 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201600430

X. Zhou, L.J. Wan, Y.G. Guo, Binding SnO2 nanocrystals in nitrogen-doped graphene sheets as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25(15), 2152–2157 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201300071

X. Wang, X. Cao, L. Bourgeois, H. Guan, S. Chen et al., N-doped graphene-SnO2 sandwich paper for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22(13), 2682–2690 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201103110

Y. Liu, C. Zhang, L. Shao, Z. Tian, Z. Deng, C. Gao, A mini review on nanocarbon-based 1D macroscopic fibers: assembly strategies and mechanical properties. Nano-Micro Lett. 9, 51 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-017-0151-7

Y. Liu, Y. Jiao, Z. Zhang, F. Qu, A. Umar, X. Wu, Hierarchical SnO2 nanostructures made of intermingled ultrathin nanosheets for environmental remediation, smart gas sensor, and supercapacitor applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6(3), 2174–2184 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/am405301v

Z. Lin, X. Xiong, J. Zheng, G. Wang, C. Yang, Three-dimensional N-doped graphene as anode material with superior cycle stability for sodium ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 202, 123–126 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2017.05.046

Y. Luo, X. Zhou, Y. Zhong, M. Yang, J. Wei, Z. Zhou, Preparation of core-shell porous magnetite@carbon nanospheres through chemical vapor deposition as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 154, 136–141 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2014.12.038

H. Wang, S. Dou, S. Wang, L. Wang, T. Wang, J. Ma, J. Zhang, Y. Yu, Synthesis of electrocatalytically functional carbon honeycombs through cooking with molecule precursors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42(10), 6472–6481 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.187

D. Zhou, X. Li, L.-Z. Fan, Y. Deng, Three-dimensional porous graphene-encapsulated CNT@SnO2 composite for high-performance lithium and sodium storage. Electrochim. Acta 230, 212–221 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.02.016

Y. Yan, F. Du, X. Shen, Z. Ji, X. Sheng, H. Zhou, G. Zhu, Large-scale facile synthesis of Fe-doped SnO2 porous hierarchical nanostructures and their enhanced lithium storage properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2(38), 15875–15882 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA02077D

X. Hou, Y. Hu, H. Jiang, Y. Li, W. Li, C. Li, One-step synthesis of SnOx nanocrystalline aggregates encapsulated by amorphous TiO2 as an anode in Li-ion battery. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(18), 9982–9988 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5TA01106J

J. Liu, Q. Zhang, J. Yang, H. Ma, M.O. Tade, S. Wang, J. Liu, Facile synthesis of carbon-doped mesoporous anatase TiO2 for the enhanced visible-light driven photocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 50(90), 13971–13974 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CC05544F

B. He, W.-C. Li, A.-H. Lu, High nitrogen-content carbon nanosheets formed using the schiff-base reaction in a molten salt medium as efficient anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(2), 579–585 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA05056H

J. Ou, Y. Zhang, L. Chen, Q. Zhao, Y. Meng, Y. Guo, D. Xiao, Nitrogen-rich porous carbon derived from biomass as a high performance anode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(12), 6534–6541 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA06614F

W. Lei, L. Han, C. Xuan, R. Lin, H. Liu, H.L. Xin, D. Wang, Nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers derived from polypyrrole coated bacterial cellulose as high-performance electrode materials for supercapacitors and Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 210, 130–137 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2016.05.158

C. Zhu, X. Xia, J. Liu, Z. Fan, D. Chao, H. Zhang, H.J. Fan, TiO2 nanotube@SnO2 nanoflake core-branch arrays for lithium-ion battery anode. Nano Energy 4, 105–112 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2013.12.018

B. Jiang, Y. He, B. Li, S. Zhao, S. Wang, Y.B. He, Z. Lin, Polymer-templated formation of polydopamine-coated SnO2 nanocrystals: anodes for cyclable lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56(7), 1869–1872 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201611160

M. Zhang, Z. Sun, T. Zhang, D. Sui, Y. Ma, Y. Chen, Excellent cycling stability with high SnO2 loading on a three-dimensional graphene network for lithium ion batteries. Carbon 102, 32–38 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2016.02.032

R. Li, B. Wang, S. Ji, P. Jin, Facile synthesis of ultrasmall stannic oxide nanoparticles as anode materials with superior cyclability and rate capability for lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 6(59), 54179–54184 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA00964F

R. Hu, Y. Ouyang, T. Liang, H. Wang, J. Liu, J. Chen, C. Yang, L. Yang, M. Zhu, Stabilizing the nanostructure of SnO2 anodes by transition metals: a route to achieve high initial coulombic efficiency and stable capacities for lithium storage. Adv. Mater. 29(13), 1605006 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201605006

W. Chen, K. Song, L. Mi, X. Feng, J. Zhang, S. Cui, C. Liu, Synergistic effect induced ultrafine SnO2/graphene nanocomposite as an advanced lithium/sodium-ion batteries anode. J. Mater. Chem. A 5(20), 10027–10038 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TA01634D

M. Yang, X. Li, B. Yan, L. Fan, Z. Yu, D. Li, Reduced graphene oxide decorated porous SnO2 nanotubes with enhanced sodium storage. J. Alloys Compd. 710, 323–330 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.03.255

R.S. Kalubarme, J.-Y. Lee, C.-J. Park, Carbon encapsulated tin oxide nanocomposites: an efficient anode for high performance sodium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 7(31), 17226–17237 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b04178

S. Li, Y. Wang, J. Qiu, M. Ling, H. Wang, W. Martens, S. Zhang, SnO2 decorated graphene nanocomposite anode materials prepared via an up-scalable wet-mechanochemical process for sodium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 4(91), 50148–50152 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA09699A

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51302079) and the National Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2017JJ1008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, J., Yuan, C., Li, H. et al. Growth of SnO2 Nanoflowers on N-doped Carbon Nanofibers as Anode for Li- and Na-ion Batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 10, 21 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-017-0172-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-017-0172-2