Abstract

In 2012, several reports were published advocating the creation of a genuine fiscal capacity at the European level, to strengthen the foundations of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) by helping member countries to adjust to asymmetric shocks. The design of a common stabilization fund should be well thought, though: what would be stabilized? When would transfers be paid? Would they be directed towards governments or individuals? How would they be financed? And would they help stabilize economies? We address these questions by outlining recent existing proposals, their features and their simulated stabilization effects. We finally underline the difficulties in implementing such a scheme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The President of the European Council wrote the report in collaboration with the Presidents of the Commission, the Eurogroup and the European Central Bank, hence the nickname “the Four Presidents’ Report”.

Its function would be stabilization, not redistribution.

Drèze and Durré (2014) proposed a different and somewhat complex system based on pooled GDP-indexed bonds as an insurance against asymmetric shocks.

In addition, there exist redistributive funds that are not related to divergences in the business cycle. Such funds are out of the scope of the paper, being of a purely redistributive type. We thank the reviewer for the distinction.

In Engler and Voigts (2013), α = 0.3.

Also, depending on the nature of shocks, specific markets (goods, labor, credit or housing) or specific accounts (balance of payments, public or private debt) may be subject to large disequilibria, and targeting directly one of these may be more effective. However, as changing the target during the operation of the scheme would be a source of tensions and uncertainty, we do not pursue this point further.

This effect derives from the fact that the reference point, X*, is the EA average and not the country-specific average. If the latter were chosen, national positions of each country with regard to the fund could be affected by forecast errors as well, but not necessarily in the same direction.

In any case, real-time uncertainty and revisions also affect other macroeconomic indicators and other policy areas (among which monetary policy and budget planning).

The size of this change could be specified.

In the ‘new’ literature on fiscal federalism, Luelfesmann et al. (2015) show that decentralization can outperform centralization provided certain conditions related to the governance structure are satisfied: namely, if the decision maker of the federal government is not benevolent, if bargaining is feasible between regional governments and if externalities are not too large. The authors disregard transaction costs in the bargaining process though. Note that their analysis deals with the implementation of local investment projects and not with automatic transfers for stabilization purposes.

However, Persson and Tabellini (1996a) had argued that federal transfers to regional governments should not provide full interregional risk sharing. Due to the moral hazard in any insurance scheme, regional governments could have fewer incentives to implement local public investment plans that could help decrease the occurrence of asymmetric shocks or help the local economy adapt to such shocks.

In the United States, for instance, under the 2008 Economic Stimulus Plan of the Bush’s administration, temporary federal transfers to households amounted to $300 and were paid to those who paid no taxes but earned an income (Pennings 2014).

Note that the low-risk region could then threaten to secede from the union. As a consequence, the high-risk region could accept to pay a lump-sum transfer (a premium) to the low-risk region, to compensate the latter for larger transfers due to its higher risk. Von Hagen (2007) also proposes this compensation.

The scheme proposed by Drèze and Durré (2014), based on the pooling of bonds, would lead to permanent transfers, with five permanent net contributors (Belgium, Austria, Finland, France and the Netherlands), and two permanent net recipients (Italy and Portugal).

For instance, in the simulated scheme studied by Dreyer and Schmid (2015), the redistribution effects counteract the stabilization effects: Ireland would have still been a net contributor to the EA budget in 2008 and 2009 because its relative richness dominates its relative GDP growth performance. Still, the conclusion on this point is strongly dependent on the features of the system.

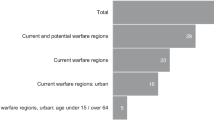

Source: own calculations based on European Commission data (EU budget and AMECO).

Eichengreen et al. (2014) give the examples of Florida and Nevada during the year crisis 2008: one year after, net transfers amounted to approximately 9 per cent of GDP for Florida (10 % in 2010) and 4 % of GDP for Nevada (5 % in 2010). Nevada was a net contributor to the federal budget in 2008 and became a net recipient the year after.

Di Giorgi (Di Giorgio 2016) analyzed the business cycle properties of Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) and the Euro Area. He found that business cycle synchronization is high between both groups, especially with regard to (the duration of) recessions.

In terms of redistributive effects, they also found that disposable income could increase much in Slovakia (69 %) and Estonia (61 %), but at the cost of a large decrease in disposable income in other countries, such as Ireland (−28 %), Luxembourg (−25 %), and Cyprus (−18 %).

Disposable income could increase up to 28 % in Greece but it could decrease as much as 9 % in Ireland and 8 % in France and Austria.

Note that Bayoumi and Masson (1998) found empirical evidence that fiscal stabilization provided by the federal government (via transfers to local governments) is more effective than that provided by the local governments in Canada. Households do not expect future tax liabilities associated with national transfers, and as a consequence, do not reduce consumption.

For a survey, see Whalen and Reichling (2015). Note that, for our subject, we focus on the effects of transfer payments and disregard those of government purchases or taxes.

The creation of Eurobonds would thus be unprecedented.

The US unemployment insurance is financed by a tax on employers that amounts to 5.4 % of labor cost. This rate is a common minimum standard across states. By experience rating, employers pay more if they fire more or if the state has not reimbursed the loan.

For earlier studies on this subject, see the assessment made by Mélitz (2004).

Over the period 1970–1994, the degree of stabilization was 47 %.

Before 1995, there was full insurance.

Yet, the German debt brake of 2009 stipulates that the federal government must cut its structural deficit to 0.35 % of GDP by 2016.

References

Allard, C., Brooks, P.K., Bluedorn, J., Bornhorst, F., Christopherson, K., Ohnsorge, F., & Poghosyan, T. (2013). Toward a fiscal union for the Euro area. IMF Staff Discussion Note 13/09.

Bargain, O., Dolls, M., Fuest, C., Neumann, D., Peichl, A., Pestel, N., et al. (2013). Fiscal union in Europe? Redistributive and stabilizing effects of a European tax-benefit system and fiscal equalization mechanism. Economic Policy, 28(75), 375–422.

Bayoumi, T., & Masson, P. (1998). Liability-creating versus non-liability-creating fiscal stabilization policies: ricardian equivalence, fiscal stabilization, and EMU. Economic Journal, 108(449), 1026–1045.

Beblavý, M., & Maselli, I. (2014). An unemployment insurance scheme for the Euro area: a simulation exercise of two options. CEPS Special Report, No. 98.

Bernoth, K., & Engler, P. (2013). A transfer mechanism as a stabilization tool in the EMU. DIW Economic Bulletin, 3(1), 3–8.

Bordo, M., Markiewicz, A., & Jönung, L. (2013). A fiscal union for the euro: some lessons from history. CESifo Economic Studies, 59(3), 449–488.

Delbecque, B. (2013). Proposal for a stabilization fund for the EMU. CEPS Working Document No. 385.

Di Giorgio, C. (2016). Business Cycle Synchronization of CEECs with the Euro Area: a Regime Switching Approach. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(2), 284–300.

Dolls, M., Fuest, C., Neumann, D., & Peichl, A. (2013). Fiscal integration in the Eurozone: economic effects of two key scenarios. ZEW Discussion Papers 13-106.

Dolls, M., Fuest, C., Neumann, D., & Peichl, A. (2014). An unemployment insurance scheme for the Euro area? A comparison of different alternatives using micro data. IZA Discussion Paper No. 8598.

Dreyer, J. K., & Schmid, P. A. (2015). Fiscal federalism in monetary unions: hypothetical fiscal transfers within the Euro-zone. International Review of Applied Economics, 29(4), 506–532.

Drèze, J., & Durré, A. (2014). Fiscal integration and growth stimulation in Europe. Louvain Economic Review, 80(2), 5–45.

Dullien, S. (2013). A euro-area wide unemployment insurance as an automatic stabilizer: Who benefits and who pays? Paper prepared for the European Commission, Social Europe.

Dullien, S., & Fichtner, F. (2013). A Common unemployment insurance for the Euro area. DIW Economic Bulletin, 1, 9–14.

Eichengreen, B., Jung, N., Moch, S., & Mody, A. (2014). The Eurozone crisis: phoenix miracle or lost decade? Journal of Macroeconomics, 39, 288–308.

Enderlein H., Guttenberg, L., & Spiess, J. (2013). Blueprint for a cyclical shock insurance in the euro area. Studies and Report No. 100, Notre Europe.

Engler, P., & Voigts, S. (2013). A transfer mechanism for a monetary union. SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2013-013.

European Commission (2006). Public finances in EMU—2006. European Economy, Reports and Studies, No. 3.

Evers, M. (2006). Federal fiscal transfers in monetary unions: a NOEM approach. International Tax and Public Finance, 13(4), 463–488.

Evers, M. (2012). Federal fiscal transfer rules in monetary unions. European Economic Review, 56(3), 507–525.

Evers, M. (2015). Fiscal federalism and monetary unions: a quantitative assessment. Journal of International Economics, 97, 59–75.

Farhi, E., & Werning, I. (2013). Fiscal unions. NBER Working Paper No. 18280.

Feyrer, J., & Sacerdote, B. (2013). How much would U.S. style fiscal integration buffer European unemployment and income shocks? (A comparative empirical analysis). American Economic Review, 103(3), 125–128.

Fichtner, F., & Haan, P. (2014). European unemployment insurance: economic stability without major redistribution of household incomes. DIW Economic Bulletin, 4(10), 39–50.

Furceri, D., & Zdzienicka, A. (2015). The Euro area crisis: need for a supranational fiscal risk sharing mechanism. Open Economies Review, 26, 683–710.

Giannone, D., Reichlin, L., & Small, D. (2008). Nowcasting: the real-time informational content of macroeconomic data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 55(4), 665–676.

Hepp, R., & von Hagen, J. (2012). Fiscal federalism in Germany: stabilization and redistribution before and after unification. The Journal of Federalism, 42(2), 234–259.

Jansen, W. J., Jin, X., & de Winter, J. M. (2016). Forecasting and nowcasting real GDP: comparing statistical models and subjective forecasts. International Journal of Forecasting, 32(2), 411–436.

Luelfesmann, C., Kessler, A., & Myers, G. M. (2015). The architecture of federations: constitutions, bargaining, and moral hazard. Journal of Public Economics, 124, 18–29.

Malkin, I., & Wilson, D. (2013). Taxes, transfers, and state economic differences. FRBSF Economic Letter, 2013-36.

Mc Morrow, K., Roeger, W., Vandermeulen, V., & Havik, K. (2015). An assessment of the real time reliability of the output gap estimates produced by the EU’s production function methodology. European Commission Working Paper, ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/events/2015/…/pdf/paper_kieran_mc_morrow.pdf.

Mélitz, J. (2004). Risk-sharing and EMU. Journal of Common Market Studies, 42(4), 815–840.

Pennings, S. (2014). Cross-region transfers in a monetary union. Working Paper, New York University.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (1996a). Federal fiscal constitutions: risk sharing and redistribution. Journal of Political Economy, 104(5), 979–1009.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (1996b). Federal fiscal constitutions: risk sharing and moral hazard. Econometrica, 64(3), 623–646.

Sanguinetti, P., & Tommasi, M. (2004). Intergovernmental transfers and fiscal behavior insurance versus aggregate discipline. Journal of International Economics, 62, 149–170.

Von Hagen, J. (2007). Achieving economic stabilization by sharing risk within countries. In R. Boadway & A. Shah (Eds.), Intergovernmental fiscal transfers. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Von Hagen, J., & Wyplosz, C. (2008). EMU’s decentralized system of fiscal policy. European Economy Economic Papers No. 306.

Whalen, C. J., & Reichling, F. (2015). The fiscal multiplier and economic policy analysis in the United States. Contemporary Economic Policy, 33(4), 735–746.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and the referees of the journal for useful suggestions and remarks. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farvaque, E., Huart, F. A policymaker’s guide to a Euro area stabilization fund. Econ Polit 34, 11–30 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-016-0038-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-016-0038-y