Abstract

The Global Justice Index is a multiyear research project conducted at the Fudan-IAS to conceptualize and measure each country’s contribution to achieving greater global justice. In 2019, we completed our research project on first-year achievements, with the rankings of nation-states at the global level based on data from 2010 to 2017. This was published titled the “Global Justice Index Report” in Chinese Political Science Review (Vol. 5, No. 3, 2020). The “Global Justice Index Report 2020” is the second annual report based on our work analyzing data from 2010 to 2018, which was concluded in 2020. In order to better measure each country’s performance and contribution to achieving greater global justice, compared to the first edition published in 2020, we have improved the model, added the refugee issue to expand the issue areas to 10, and added new indicators, regional analysis and comparison in this report. The report comprises five main sections. In the introduction, we discuss the development of the conceptual framework and evaluative principles to justify our selection of dimensions and indicators for measurement. Next, in the section of methodology, we discuss the production, normalization, and aggregation of the raw data and the generation of the final results. In the findings section, we report the data, indicators and our results for the ten issues, and provide regional comparisons. And then, in the following section we present the main results, and report the ranking of each country’s contribution to achieving greater global justice. In the final section, we discuss the applications and limitations of the index, and its potential further research trajectories.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The Global Justice Index is a multiyear research project conducted at the Fudan-IAS to conceptualize and measure each country’s contribution to achieving greater global justice. In 2019, we provided our first-year achievements with the rankings of nation-states at the global level from 2010 to 2017. Based on the results, we have published a book in Chinese and an academic paper in English, which has received widespread attention. Building on the success of the previous year’s work, in 2020, we intend to provide our second-year results with the rankings of nation-states at the global level from 2010 to 2018. This year’s Global Justice Index (2020) report consists of five sections: introduction, methodology, results, analysis and conclusion.

In the introduction, we highlight our theoretical innovation by discussing the development of the conceptual framework to justify our selection of issues, dimensions and indicators for measurement. In addition, we present some major changes in this year’s report compared with last year’s report. Next, in our methodology section, we introduce our methods for production, normalization, and aggregation of the raw data and the generation of the final results. In the results section, we present the rankings of nation-states’ contribution to global justice from 2010 to 2018. Following the results section, we provide regional comparisons with detailed policy analysis assisted with various visualization tools. In the last concluding section, we discuss the applications and limitations of the index, and its potential further research trajectories and policy implications for advancing global justice.

Global justice is a broad concept composed of multilevel and multidimensional aspects belonging to both normative and empirical realities. A coherent, integrated theoretical framework that covers the normative basis and various empirical dimensions is therefore necessary to address some of the basic and important questions under study. Our Global Justice Index study began with the conceptualization of global justice based on a theoretical paper titled “Conceptualizing and Measuring Global Justice: Theories, Concepts, Principles and Indicators,” coauthored by the project leader, Sujian Guo et al. published in Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences (Vol. 12, No. 4, 2019). The paper discusses theories, concepts, evaluative principles, and methodologies related to the study of global justice.

In the theoretical paper above (Guo et al. 2019), we attempt to clarify how to conceptualize global justice, how conceptual indicators can be selected and justified by theories, and how those indicators can be consistent with the concept of global justice. Through the synthesis of multiple theories and intellectual traditions in various cultural and political contexts, we conceptualize global justice from three main approaches—rights based, goods based, and virtue based—to develop a normatively based theoretical framework for measurement. Rights-based conceptualization focuses on the basic principles, rules, and sources of legitimacy of justice (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948; Rawls, 1971, 1999). Goods-based conceptualization concentrates on the material and institutional supports that governments or institutions are obliged to provide (Arneson, 1989; Freeman, 2006; Nussbaum, 2006, 2011; Richardson, 2006). And virtue-based conceptualization regards justice as a virtue that an individual is willing to pursue rather than a regulation an individual is forced to comply with (Mo, 2003). The relationship between the three approaches of conceptualization is interdependent rather than separate, which indicates three interrelated components of a holistic whole. Additionally, the three approaches are complementary rather than competing, with the rights-based conceptualization forming the basic structure (“the bones”), the goods-based conceptualization providing substantial material supports (“the muscles”, and the virtue-based conceptualization emphasizing personal motivation and internalized willingness (“the heart)” (Guo et al., 2019).

Based on the aforementioned theoretical framework, we propose two evaluative principles to further bridge the gap between theory and practice to determine and justify our selection of issue areas for evaluation. We call the two principles Common but Differentiated and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC) and Cosmopolitan but Due-diligent Responsibilities (CDDR). CBDR-RC addresses the issues “for which no single nation-state can be held directly accountable or responsible, matters that can only be tackled through the globally concerted efforts of all stakeholders” (Guo et al. 2019). For example, it is the responsibility of all to protect the climate system and ecological balance, and environmental protection is a task that cannot be handled by one country on its own. The principle of CBDR-RC, first adopted by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and reaffirmed in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, combines normative legitimacy and historical rationality. Although it was a principle that first aimed to determine the responsibilities of each country for climate change, it has been expanded to other global justice areas such as combatting transnational crime and global peacekeeping.

The second principle, CDDR, addresses that “all-nation-states are morally obligated to provide cosmopolitan aid, in which context the least advantaged will have a due-diligent responsibility” (Guo et al. 2019). This principle is based on the concept of “mutual accountability” proposed in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, adopted in 2005 at the Second High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness to promote better cooperation between different actors in aid and development. This principle views such obligations as part of domestic affairs, such as anti-poverty and education policy, in the context of which nation-states are expected to provide material and institutional assistance to their citizenry within their territories.

According to the principles of CBDR-RC and CDDR, we have selected two clusters of global justice issue areas for practical measurement. Those issue areas that follow the principle of CBDR-RC are (1) climate change (global warming), (2) peacekeeping, (3) humanitarian aid, (4) terrorism and armed conflicts, (5) cross-national criminal police cooperation, (6) refugees; and those belonging to the principle of CDDR are (7) anti-poverty, (8) education, (9) public health and (10) the protection of women and children.

This year’s Global Justice Index study is not simply a continuation of last year’s work. To further improve the quality of our index, we have made a few major modifications. First of all, we have perfected our selection of issue areas and indicators by adding a brand new issue area and more indicators to our study. In the Global Justice Index (2019), we have selected nine issues areas to construct the index. The issue of refugees has been included in this year’s Global Justice Index as more and more attention has been devoted to the fermenting refugee crisis. For other issue areas, indicator systems have been either kept unchanged or improved. Second, we have slightly modified our research methodology to better calculate the index (for more information, please see the next section). Third, we have changed our indicators and included more data in our calculation. Last, we have strengthened our analysis section by incorporating and discussing more literature and policy implications. As such, readers from different backgrounds can all benefit.

Due to these new changes, readers may find that some countries’ rankings in this year’s Global Justice Index are quite different from those in the Global Justice Index (2019), while other countries’ rankings have not changed substantially. This should not be a surprise to our readers. Global justice is a cutting-edge research field which involves sophisticated materials, a large volume of data and a changing international landscape. We aim to keep our results consistent across different years. At the same time, we do make necessary and important modifications to our research design in light of a changing international environment and the availability of new and better data.

2 Methodology: Construction of the Global Justice Index

In this study, we classify our data into four levels: indicators, dimensions, categories, and issues. The first and lowest level of our data provides the information on indicators, which is our raw data. The second level is named dimensions, which usually comprises several related indicators. The third level is categories and comprises several related dimensions. And the highest level is the issue index, usually calculated based on two categories: contribution and performance.

The global justice index is calculated as follows:

2.1 First step: Convert Indicator Indices

To ensure comparability between indicators, we use the following two formulas to convert the raw data into comparable indicators:

where \(actual {value}_{ij}\) indicates the actual value of an indicator in country i in year j, \(\mathrm{min}({actual value}_{.j})\) is the minimum value of an indicator among all countries in year j and \(\mathrm{max}({actual value}_{.j})\) is the maximum value of an indicator among all countries in year j. If an indicator positively relates to global justice, the first formula is used to convert the raw data; if not, the second formula is used.

2.2 Second step: Population-Based Weighting

Consciously, efforts made to raise the welfare of their populations to the same level have a comparatively larger overall impact in countries with larger populations; therefore, we weight indicators based on population size. We proceed as follows:

First, we calculate the weighted average of an indicator as per the following formula:

where \({ii}_{mj}\) is the weighted average of an indicator. \(i{i}_{ij}\) is the actual value of an indicator in country i in year j.\(populatio{n}_{ij}\) is the population size of country i in year j.

Second, we calculate the weight of each country on an indicator as follows:

where \({ss}_{ij}\) is the weight of country i in year j.

Third, we calculate the score for an indicator in country i in year j as follows:

where \({II}_{ij}\) is the score of an indicator in country i in year j. We use \({II}_{ij}\) to further calculate the dimension global justice.

2.3 Third step: Calculate the Scores of Both Dimension Indices and Category Indices

For each variable, we calculate the score of the dimension index as follows:

where \({II}_{ij}\) is the score of an indicator in country i in year j, and K is the number of indicators in a specific dimension in country i in year j.

Similarly, we use \({DI}_{ij}\) to further calculate the score of category indices as follows:

2.4 Fourth step: Calculate the Score of the Issue Index

We use \({VI}_{ij}\) to further calculate the score of each issue in county i in year j as follows:

2.5 Last step: Calculate Global Justice Index

We use the following formula to calculate the score of the global justice index in country i in year j:

where \({GJ}_{ij}\) is the score of global justice in country i and year j.\({ISI}_{ijk}\) is the score of issue k in country i in year j.

3 Findings

3.1 Issue 1: Climate Change

3.1.1 Introduction

Nowadays, more and more people around the globe have realized that climate change is a global challenge facing our planet, closely related to the survival of human beings and the continuation of our civilization. Climate change will bring about many problems, such as extreme weather, melting ice and snow, rising sea levels, frequent mountain fires and so on. Climate change has been a feature of the evolution of the earth itself, and it has long been a completely natural phenomenon, without significant human intervention. But with the development of mankind, more and more human activities have been linked to climate change. For example, the industrial production process needs to consume a substantial amount of fossil energy, which causes a lot of greenhouse gases to be emitted into the air, further enhancing global warming. Many activities in our daily lives are also emitting greenhouse gases into the air. The increase in the earth's temperature caused by climate change will have an irreversible impact and cause harm to human production and life, so all countries in the world must act.

The issue of climate change is also a global justice issue, because it involves the distribution of responsibilities and obligations between all of the developing and developed countries in the world. The signing of the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015 was a milestone event for dealing with the climate change issue, which shows the strong determination of governments of all countries to cooperate to solve the problem of global warming. However, the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Agreement in recent years has cast a shadow on global climate governance. With the victory of Joe Biden in the 2020 US election, the United States is very likely to return to the field of global climate governance and even push countries to take more measures to deal with climate change. The Climate Ambition Summit which was held in December 2020 shows a new surge in action and ambition to control global warming. As a matter of fact, countries are taking various measures to advance their national determined contribution targets, but how well each country is doing in reality remains unknown. Our Global Justice Index research will answer this question through data analysis.

3.1.2 Dimensions and Indicators

The issue of global warming has prompted worldwide discussion. At the beginning of this century, Thomas Crowley published an important research paper in Science, arguing that “natural variability plays only a subsidiary role in the twentieth-century warming and that the most parsimonious explanation for most of the warming is that it is due to the anthropogenic increase in GHG”.Footnote 1 This research finding is consistent with the definition of climate change in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change which defines climate change as a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods. According to these scientific research results and the definition of climate change of the United Nations, our empirical analysis for measuring countries’ contributions to solving climate change includes four dimensions: energy consumption, electricity production, CO2 and forests.

We have obtained highly reliable open source data from prestigious international organizations, research institutions, and multinational companies, such as forest data from the United Nations Environment Programme, and carbon dioxide-related data from the Global Carbon Project. Based on these open source data, we design three to five indicators for each dimension. For example, in the energy consumption dimension, our indicators include primary energy consumption in total, primary energy consumption per capita, oil consumption, natural gas consumption, and coal consumption. In the electricity production dimension, our indicators include electricity production in total, electricity production from nuclear sources, electricity production from hydroelectric sources, Electricity production from renewable sources excluding hydroelectric. In the dimension of CO2, our indicators include C02 emissions, C02 emissions per GDP and C02 emissions per capita. In the forest dimension, our indicators include forest area in total, forest area change rate, forest area per capita, forest coverage, planted forest area. In order to better reflect the contributions of countries around the world in the current battle against climate change in the past decade, the time span that we focus on in this project is from 2010 to 2018. Last year's Global Justice Index research on climate change covers 192 countries around the world, but the time frame is from 2010 to 2014. This year we have done a better job in terms of time frame than last year, but this year's research can only cover 75 countries, which leaves some small and medium-sized countries omitted. We are fully aware that the scale of national coverage is a major shortcoming of this year’s research due to the lack of reliable data, but the comprehensive indicator system can make sure that we can have a sound calculation of 75 countries’ contributions to global justice from the perspective of fighting climate change. We will keep looking for better and comprehensive data to cover more countries in the future (Table 1).

3.1.3 Results

In this section, we present the ranking results of the countries’ contributions to global justice from a climate change perspective (Table 2). Table 2 shows 9 years of results from 2010 to 2018 in 75 countries.

The table above shows that from 2010 to 2018, Brazil, Canada, Sweden, Russia, France, Finland, Peru, Colombia and other countries have consistently performed well in climate change. Among them, Brazil, Russia, Peru and Colombia are developing countries while Canada, Sweden, France and Finland are developed ones. China's performance in climate change over the previous years has been very impressive, and it is a good model for developing countries. In 2010, China ranked 18th in terms of climate change performance. After that, the progress was very obvious. It entered the top 10 in 2014 and has risen to 5th in 2018. Among the entire 75 countries, developing countries have done worse than developed countries. Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, Trinidad and Tobago, Qatar and other countries ranked low. In addition, some countries’ climate change ranking has shown great volatility. For example, the United Kingdom has risen from 48 in 2010 to 34 in 2018, showing a clear upward trend; Algeria has dropped from 26 in 2010 to 58 in 2018, showing a clear downward trend; and Japan first drops and then rises, forming a V-shaped fluctuating change.

Brazil's ranking from 2010 to 2018 is quite stable because its vast forests make it score higher in the forest dimension, and its performance in the other three dimensions is also excellent. Brazil has a vast Amazon forest, however, the forest area change rate in Brazil has consistently been negative from 2010 to 2018. As such, Brazil ranks 5th in the forest dimension score, i.e. not the first in the world. Canada scored higher in the dimensions of forests and electricity generation. However, because it scored slightly lower in the dimensions of carbon emissions and energy consumption, in the end it ranked second after Brazil. Sweden, which ranked third in 2018, scored lower than Canada in the dimensions of forests and electricity generation. Sweden has a higher score in carbon emissions, and has a slightly higher score in energy consumption than Canada. Russia scored very high in the dimensions of forests and electricity generation, and scored low in terms of carbon emissions and energy consumption. Thanks to the rapid development and energy saving and emission reduction policies in the past 10 years, China scored high both in electricity generation and carbon emissions. These significant improvements are key reasons why its ranking rose from 18th in 2010 to 5th in 2018. France has a high score in the dimensions of carbon emissions and electricity generation, and a low score in the dimensions of forests and energy consumption. Contrary to France, Finland has a low score in the dimensions of energy consumption and carbon emissions and has a medium score in the dimension of electricity generation. Finland’s forest dimension score is higher. Peru scored very highly in the energy consumption, carbon emissions, and forest dimensions, but it scored very low on electricity generation. Similarly, Colombia also has higher scores in the dimensions of energy consumption and carbon emissions; but its score in the electricity generation dimension is slightly higher than Peru, and its score in the forest dimension is slightly lower than Peru, thus the overall ranking is lower than Peru.

The lowest ranking countries in the field of climate change are Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, Trinidad and Tobago, and Qatar. The major reason for the low ranking of these countries is that they are generally less capable of addressing climate change. Part of the reason comes from their low scores on forests and carbon emissions. Both Saudi Arabia and Qatar are Middle Eastern countries with relatively few forest resources. Although the scores of these two countries in the forest dimension are on the rise, they are still relatively small compared to other countries. Qatar performed worst because of its poor performance in all aspects. Kazakhstan's forest score is also relatively low, and the gap with Saudi Arabia is not very large, but Kazakhstan's performance in carbon emissions and power generation is weaker than Saudi Arabia; thus it ranks lower than Saudi Arabia.

The United States’ rankings over the years have not been in the top 10. The Democratic Party in the United States is more concerned about climate change issues than the Republican Party. During the Obama administration, the United States performed relatively well on climate change. However, after the 2016 U.S. election, Donald Trump became President of the United States. He strongly supported traditional energy, not new energy, and was very indifferent to the issue of climate change. This led to a significant decline in the ranking of the United States in 2018. The British government has attached great importance to climate change issues in the past few years.Footnote 2 Judging from the scores of the four dimensions, the UK is in an upward phase in the four dimensions of electricity generation, carbon emissions, energy and forests. According to this trend, the UK's ranking in the future is expected to rise.

Germany's ranking is in a downward trend at this stage. On the whole, Germany's performance in the three dimensions of power generation, carbon emissions and forests is good. However, as a major manufacturing country, Germany's carbon emissions are relatively large, thus dragging down Germany's overall performance. Germany changed its attitude towards nuclear power generation after the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan. The Merkel government has gradually shut down more nuclear power generation in the past few years and plans to close all nuclear power plants in the country by 2022. This has caused Germany's score in power generation to drop substantially, which is also an important reason for the decline in Germany's ranking year by year. But in the long run, we are relatively optimistic about Germany's ability to deal with climate change. Germany is a leader and pioneer in developing renewable energy and promoting low-carbon development. The German government believes that climate protection not only provides long-term guarantees for sustainable economic development, but also brings direct benefits to the German economy. Therefore, it has been actively participating in and promoting action against climate change. Looking at recent history, we found that Germany passed the "Energy Utilization and Climate Protection Package" in 2007, and subsequently passed the "Biofuel Oil Ratio Law", the "Renewable Energy Heating Law", and the "Vehicles A series of related legislations including the Purchase Tax Reform Law, which stipulates that the new car purchase tax rate is linked to the size of the vehicle engine and the level of carbon dioxide emissions. Germany also has strong technical strength in the development of wind power generation, and its ranking may show an upward trend in the future.

India's ranking is generally in decline. As the second largest developing country in the world after China, India is facing great pressure on the issue of climate change. India's scores on the three dimensions of energy, carbon emissions and power generation are all falling, and the only growth is in the forest dimension. From 2010 to 2018, India’s economy and population are still growing rapidly, especially since the Modi government came to power, India’s economic development has accelerated. Some studies have found that India has begun to suffer severe impacts from climate change, especially in the agricultural sector.Footnote 3 But India has yet to find a better way and build greater determination to deal with climate change.

The Dutch ranking in climate change has been around 60 for a long time, which may surprise some readers. As a major developed country, the performance of the Netherlands in tackling climate change is far worse than other developed countries and even many developing ones. Our research shows that the Netherlands performs well in the two dimensions of energy and carbon emissions, but its performance in the two dimensions of forests and power generation is poor, which is the main reason for its relatively backward ranking. Electricity generation in the Netherlands is highly dependent on thermal power plants, which rely on a large amount of fossil energy. The situation in Iceland is similar to that in the Netherlands. Iceland is even worse than the Netherlands in the three dimensions of carbon emissions, power generation and energy consumption, but it performs much better than the Netherlands in the forest dimension. As a developed country, Belgium ranks slightly higher than the Netherlands and Iceland, but it is also in a relatively backward position within the group of developed countries. The reason is that from a data point of view, Belgium ranks relatively low in the two dimensions of forests and power generation.

Japan's ranking decline over the past 9 years is mainly related to the leak at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in 2011. After the accident, the abandonment of nuclear power was one of the main response measures of the Japanese government. In May 2011, Japan’s last nuclear power plant in operation, the Hokkaido Tomari Nuclear Power Plant, ceased power generation. In July 2011, the then Prime Minister of Japan proposed the goal of "establishing a society without nuclear power." Because of the reduction in nuclear power, Japan’s score in power generation has fallen. The later prime minister led the formulation of Japan's new energy and environmental strategy, making it clear that Japan's dependence on nuclear power will be zero by 2030. As a result, Japan’s score on the power generation dimension has dropped consistently, leading to a decrease in its ranking. However, in recent years, Japan has seen some new changes in its attitude towards nuclear power, and it has begun to again support a role for nuclear power in the national energy system. This is the main reason why Japan's climate change rankings are beginning to rise.

3.1.4 Regional Analysis

In 2018, the top Ten countries in the field of climate change were Brazil, Canada, Sweden, Russia, China, France, Finland, Peru, Colombia, and the Philippines. Among the top ten countries, there are four countries in the Americas, two Asian countries, four European countries, but African countries are not included in the top ten. There are six developing countries and four developed countries (Fig. 1). This shows that the degree of economic development is not necessarily related to the response to climate change. Both developed and developing countries have the opportunity to play an important role in the response to climate change. These countries are able to rank high in the field of climate change because they have some common characteristics. First, these countries generally attach importance to climate change issues. Different countries have different understanding of climate change issues.Footnote 4 For example, the Trump administration of the United States has a very negative attitude towards climate change, and the U.S. government even withdrew from the Paris climate agreement. However, these top 10 countries have not only signed and maintained the Paris climate agreement, but have also been taking many measures to increase their nationally determined contributions. Second, these countries generally have no obvious shortcomings in the four dimensions of energy consumption, carbon emissions, power generation and forests. In other words, the top-ranked countries have performed well in major aspects of tackling climate change. Finally, these countries tend to be particularly prominent in certain aspects of responding to climate change. For example, Russia and Canada have outstanding performance in the forest dimension. China has outstanding performance in the two dimensions of power generation and forests. After signing the Paris Agreement in 2015, China has become more proactive in promoting the transition to low-carbon social and economic development. Renewable energy power generation is developing rapidly in China. China has also invested a lot of money, manpower and material support in afforestation.

It should be noted that the analysis of climate change is based on statistical data of 75 countries, so it reflects the relative ranking of these 75 countries. From an absolute point of view, the lower-ranking countries in the climate rankings may not be worse.

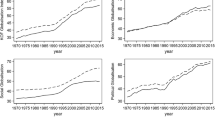

Next, we classify countries according to their continents. These continents include Asia, Europe, North America, Latin America, Africa and Oceania. The ranking of each continent is obtained by calculating the average of the rankings of these countries. We drew a line chart to achieve a visual presentation to compare the differences in the contribution of various continents to climate change.

Seventy-five countries are included in the six continents, of which there are more countries in Europe and Asia and less countries in Oceania and North America (Fig. 2). According to the average number of scores, the top overall rankings are North American countries, followed by Latin American countries and European countries. The lowest overall ranking is African countries. The reason why North American countries rank high is because North America has only two countries in our ranking, the United States and Canada. The rankings of these two countries are very high. Africa is at the bottom of the ranking because the selected African countries are generally at the bottom, and no country has performed well in addressing climate change. From the comparison of various continents, the ability and level of various regions to cope with climate change are extremely uneven. Africa, with the largest concentration of developing countries, needs more support and help from other countries.

Asia In 2018, we found that the top three Asian countries are China, the Philippines, and Japan, and the bottom countries are Qatar, Kazakhstan, and Saudi Arabia. After the Copenhagen Conference, China changed its attitude towards climate change and began to take more active measures to address the challenges of climate change. In 2013, the Chinese government officially released the "National Climate Change Strategy." In 2015, China signed the Paris Climate Agreement and actively fulfilled its emission reduction obligations. At the General Debate of the 75th UN General Assembly in 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that China will increase its nationally determined contribution and adopt a series of more powerful measures to strive for the peak of carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and strive to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Among the top three countries in Asia, China scores higher in the power generation and forest dimensions, and lower in the carbon emissions and energy consumption dimensions. The main reason why China scores high in the power generation dimension is that China is vigorously developing nuclear power, hydropower, wind power and solar photovoltaic power generation. Meanwhile, the Philippines scores high in carbon emissions and energy consumption, but it scores very low in power generation, and its performance in the forest dimension is average. The economic foundation of the Philippines is relatively weak. Although it has maintained rapid growth from 2010 to 2018, the economic structure of the Philippines is dominated by the service industry, so its industrial and manufacturing capabilities are not strong. Service-oriented economies tend to have relatively low carbon emissions and energy consumption, so the Philippines performs better in these two dimensions. Japan’s scores on carbon emissions and energy consumption are slightly lower than those of the Philippines, and its scores on the forest dimension are better However, its score in the power generation dimension has shown a clear downward trend. As mentioned above, this is mainly because nuclear power generation has been greatly affected in Japan. Japan is a major manufacturing country in Asia and the world, with strong demand for energy and electricity. Although the leak at the Fukushima nuclear power plant caused the Japanese people to strongly resist nuclear power generation, Japan currently does not have the ability to completely get rid of nuclear power generation.Footnote 5 As a kind of clean energy, nuclear power generation is gradually recovering in Japan, which will help Japan better achieve its emission reduction targets.

In 2018, we found that the Asian countries ranked at the bottom were Qatar, Kazakhstan and Saudi Arabia. Qatar and Saudi Arabia are desert countries in the Middle East, and Kazakhstan is a landlocked country in Central Asia. These three countries are very rich in oil and natural gas resources, and exporting energy is an important pillar of their own economy. Affected by economic inertia and inherent interests, the three countries have relatively negative attitudes towards the development of new energy sources and are less active in responding to climate change. In addition, the three countries have relatively few forest resources, and as a result their capacity for carbon neutrality is comparatively insufficient. These countries should actively adapt to the requirements of the climate change era, reduce their dependence on fossil energy and actively open up new economic development paths to promote the transition of their entire societies and economies to low carbon.

Europe In 2018, we found that the top three European countries were Sweden, Russia, and France. Sweden and France are major economic powers in Europe, with relatively strong technological and industrial capabilities. In contrast, Russia's economy is heavily dependent on the export trade of oil and natural gas and other resources, and its level of industrialization is relatively weak. The reason why Sweden, Russia and France can rank highly is mainly because they have an outstanding performance in certain dimensions. For example, Sweden scores relatively highly in the carbon emissions, energy consumption and forest dimensions, but it scores poorly in the power generation dimension; Russia scores very highly in the forest dimension, mainly due to its vast territory and high forest coverage. Russia also scores relatively highly in the dimensions of carbon emissions and energy consumption. Although Russia is a major producer and exporter of oil and natural gas, Russia's own manufacturing industry is underdeveloped, and its own carbon emissions and energy consumption are smaller than those of some developed countries. Russia has made slow progress in the development of renewable energy, with a slightly lower score in the power generation dimension. France has a higher score in the carbon emissions and energy consumption dimensions, which is inseparable from France’s active transition to a low-carbon economy. It is a developed country and a role model in this area. However, France has a low score in the power generation and forest dimensions, especially in the use of renewable energy to generate electricity. France is not in a leading position.

In 2018, we found that the bottom three countries in Europe were Iceland, Ukraine and the Netherlands. Both Iceland and the Netherlands are developed countries. Iceland's ranking lags behind other European countries because of its poor performance in power generation, carbon emissions and energy consumption. Iceland is located in the northern part of Europe where the climate is relatively cold, and economic activities require a lot of energy consumption and produce a lot of greenhouse gas emissions. However, Iceland has a “bright spot” in power generation: its hydropower and geothermal power generation systems are relatively developed. Iceland’s hydropower performance is included in our research, but its performance in geothermal power generation is currently not included, which has somewhat dragged down Iceland’s ranking.

The Netherlands ranked 60th in climate in 2018, and its performance in the two dimensions of energy consumption and forests was poor. The Netherlands has a concentration of energy and emission-intensive industries and is heavily dependent on fossil fuels. The academic community is paying increasing attention to how the Netherlands is responding to climate change.Footnote 6 From 2008 to 2018, the share of fossil fuels in the total primary energy supply only slightly decreased, from 92 to 90%. The Netherlands is the most economically developed country in the world, and its current performance in tackling climate change is unsatisfactory. The Dutch government is taking a series of measures to promote a cost-effective transition to a low-carbon economy. One of these measures will result in at least 70% of electricity coming from renewable energy sources (mainly wind energy and photovoltaic power generation). In addition, the Netherlands has a forest coverage rate of 11%, and the per capita forest area is low (only 0.02 hectares/person), so in the future it is also necessary to improve its performance in the forest dimension. Ukraine is a large agricultural country and has always been known as the "granary of Europe." Because agricultural activities are greatly affected by climate change, the issue of global warming has gradually attracted the attention of Ukrainians. However, Ukraine’s economic activities rely heavily on fossil energy and its energy efficiency is low, which has caused Ukraine’s poor performance in carbon emissions and power generation. Ukraine is very interested in the use of renewable energy, especially in the application of power generation, and is actively promoting the development of photovoltaic power generation projects.

North America In 2018, Canada's ranking was better than that of the United States. This was mainly due to the Canadian government's long-term continued attention to climate change issues. Canada’s only shortcoming is in power generation, especially in the use of renewable energy for power generation. Although the United States is the most economically developed country in the world and has the strongest scientific and technological strength, it is not the most outstanding in addressing the climate change issue. During the Obama administration, the United States not only signed the Paris Climate Agreement, but also actively promoted the development and use of renewable energy. However, the U.S. Republican Party, especially the Trump administration, is skeptical of climate change and has a negative attitude towards climate change.Footnote 7

Latin America In 2018, we found that the top countries in Latin America were Brazil and Peru, and the bottom countries were Argentina and Trinidad and Tobago. Brazil ranks first not only in Latin America, but also in the entire group of 75 countries, as discussed above. It is worth noting that Brazil's virgin rainforest is decreasing. Studies have found that compared with the Democratic Congo and Indonesia, which also have tropical rainforests, Brazil’s virgin forest has been reduced by twice that of Indonesia and five times that of the Democratic Republic of Congo.Footnote 8The reason why Peru ranks highly is that Peru performs very well in the three dimensions of energy consumption, carbon emissions and forests. Argentina is one of the more economically developed countries in Latin America, with relatively developed industry and agriculture and relatively large carbon emissions. Argentina's support for renewable energy is relatively small, and the performance in renewable energy power generation is poor. Trinidad and Tobago is an island country whose economy is dominated by energy development and processing industries, and its ability to cope with climate change is insufficient, so it ranks at the bottom among Latin American countries.

Africa Among the 75 selected countries, only Morocco, Egypt, Algeria and South Africa are in Africa, and their rankings are relatively low. Compared with countries on other continents, the performance of African countries in dealing with climate change is relatively poor and they are more vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change.Footnote 9 The reason is that although the carbon emissions of African countries are generally small, their energy use efficiency is generally low, and their performance in the two dimensions of power generation and forests is also relatively poor. Morocco ranks highly in Africa because it scores highly in the dimensions of carbon emissions and energy consumption, which does not mean that Morocco’s economic activities are very focused on improving energy efficiency. The main reason is that Morocco’s economic pillars are tourism and fisheries, and industry and manufacturing are underdeveloped. South Africa ranks behind because it is the largest economy in Africa, with relatively developed industrial and manufacturing sectors, and relatively large carbon emissions.

Oceania In 2018, New Zealand and Australia in Oceania ranked 26th and 47th, respectively, with New Zealand performing much better than Australia. Both New Zealand and Australia performed relatively well in terms of carbon emissions and energy consumption, but their performance in the two dimensions of forests and power generation was not satisfactory. In particular, Australia has been performing poorly in forest resource protection. The annual wildfires burn down and devour a large amount of forest, resulting in a negative rate of change in Australia's forest cover. Global warming continues to pose a threat to Australia's forests, and more forest resources may be destroyed in the future. Australia needs to show greater determination to work with the rest of the world to cope with the challenges brought about by climate change.

3.1.5 Conclusion

The need to deal with the challenges brought about by climate change is urgent. Countries around the world should strengthen cooperation and strive to achieve the long-term goal set in the Paris Agreement, that is, to control the global average temperature rise to within 2 °C compared with the pre-industrial period, and efforts should be made to limit the temperature rise to within 1.5 °C. To achieve this goal, more and more countries have adopted various measures to increase their nationally determined contributions. For example, China has made a clear commitment to achieve a peak in carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Our research has found that countries around the world currently differ greatly in their capacity to deal with climate change issues. This difference is also reflected in their nationally determined contributions.Footnote 10Some countries, as represented by China, have the ability to increase their national independent contributions, but most developing countries urgently need support and assistance from developed countries in terms of capital, technology and science and technology. In particular, African countries need the support of developed countries.

There is also a certain degree of differentiation within developed countries. Some countries have taken a leading position in the development of renewable energy, while the pace of some developed countries has been relatively slow. The Biden administration announced its return to the "Paris Agreement" as soon as it took office. This is a very positive signal for the world's response to climate change. With the support of world powers such as China and the United States, we can expect the world to cooperate closely on the issue of climate change.

3.2 Issue 2: Peacekeeping

3.2.1 Introduction

War and peace have always accompanied the development of human civilization. Once a war breaks out, justice disappears. Although there has been no major global war since the end of World War II, local conflicts have not ceased and have intensified in some places. Regional conflicts surrounding resources, borders, ethnic conflicts, historical disputes and other factors have always been important factors threatening regional security and development. There can be no justice without security. Therefore, resolving regional conflicts is a long-term focus of the international community, as well as a difficulty and challenge. After World War II, the United Nations came into being. Maintaining peace, preventing and resolving conflicts and wars are important goals of the United Nations. Since the mid-twentieth century, peacekeeping operations have become an important task of the international community, and especially of the United Nations. More and more countries are sending military personnel to participate in UN peacekeeping operations. Some countries provide large amounts of financial support to maintain the smooth progress of UN peacekeeping operations. After the end of the Cold War, United Nations peacekeeping operations have become an important means of regional conflict management and resolution and have received extensive attention and support globally.

The content and scope of peacekeeping work has undergone great changes from the mid-twentieth century to today.Footnote 11Our understanding of peacekeeping is constantly deepening. The traditional understanding is that peacekeeping work is mainly related to regional security issues, but now peacekeeping work also involves human rights protection, the establishment of the rule of law- and the organization of elections. While UN peacekeeping operations have produced good results, we also find that the willingness and ability of countries to participate in UN peacekeeping is undergoing great changes. In the early days of the rise of peacekeeping, Western developed countries were the most important participating countries. In the following decades, developing countries continued to join the peacekeeping work and gradually grew into the backbone of the UN peacekeeping work. Although developed countries are still actively participating in UN peacekeeping operations, the number of personnel dispatched shows a clear downward trend. Our research analyzes the contributions of countries around the world to UN peacekeeping operations over the past few years. This is conducive to analyzing the changing trends in UN peacekeeping operations and provides a reference for the future reform and development of UN peacekeeping.

3.2.2 Dimensions and Indicators

In general, there are two types of peacekeeping missions. The first type of peacekeeping mission is conducted by the United Nations (UN) and the second is conducted by various regional organizations. Both types of peacekeeping activity are important, but scholars and policy analysts have different opinions on each of them.Footnote 12 In general, more people support peacekeeping operations conducted by the United Nations. The reason is obvious. The United Nations enjoys compelling, overwhelming and incomparable authority in peacekeeping. The peacekeeping efforts of regional organization enjoy certain advantages, but they cannot be comparable to the UN peacekeeping in terms of authority and capacity. In addition, UN peacekeeping data are available online with detailed information about countries’ contributions in various ways. Regional peacekeeping data are not fully open source data (Table 3).

As such, our empirical analysis of countries’ contributions to peacekeeping is limited to UN peacekeeping contributions. It includes two dimensions: personnel contribution and financial contribution. Personnel contribution is measured by the troops and police indicator, while the financial contribution is measured by the donation indicator. These data are all available on the UN peacekeeping website and international Peace Institute. Our time span is from 2010 to 2018. In the future, we may consider including regional peacekeeping contributions to our analysis.

3.2.3 Results

In this section, we present the ranking results of countries’ contributions to global justice from a peacekeeping perspective (Table 4). Table 4 shows nine years of results from 2010 to 2018 in 192 countries.

The above table shows that from 2010 to 2018, countries such as the United States, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Rwanda, India, China, Pakistan, Nepal, Japan*, and France have consistently performed well in peacekeeping. Among them, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Rwanda, India, China, Pakistan and Nepal are all developing countries, while the United States, Japan and France are developed countries. Among them, the United States, China and France are permanent members of the Security Council. Judging from the performance of the top ten, developing countries perform better than developed countries in peacekeeping. This result shows that the degree of economic development itself may not be the main factor influencing the country’s participation in UN peacekeeping. Among the top ten countries, six countries are in Asiad, one country is in North America, one country is in Europe, no country is in Latin America, two countries are in Africa, and no country is in Oceania. From the perspective of geographical distribution, Asian countries have contributed more to peacekeeping than other continents.

The United States has long been ranked No. 1 for its contribution to peacekeeping, and it is a model for developed countries’ contribution to UN peacekeeping. The United States is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and the most powerful country in the world. It has also played the role of "world police" for a long time. The number of peacekeepers (military and police) sent by the United States used to be large, but the number of peacekeepers has gradually decreased over the past few years. At the same time, the United States has increased its financial support for UN peacekeeping. Although the number of peacekeepers dispatched by the United States is decreasing, financial support for peacekeeping has been increasing, which has resulted in the United States ranking first in peacekeeping. In fact, not only is the United States gradually reducing the number of peacekeepers it dispatches, but other developed countries are also reducing the number of peacekeepers they dispatch. The reason why developed countries choose to reduce personnel dispatch and increase financial support is likely to be related to the fact that domestic public opinion is very concerned about casualties among peacekeepers.Footnote 13

Ethiopia is a country with relatively large economic strength, land area and population in Africa. In the past 9 years, Ethiopia’s contribution to UN peacekeeping has jumped to second place in the world. The main reason behind this is that Ethiopia is greatly increasing the number of peacekeeping personnel. Taking 2018 as an example, Ethiopia was the country that sent the most peacekeepers. The situation in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and China is similar to that of Ethiopia. They have all gradually increased their numbers of peacekeeping personnel. This also shows the strong willingness of these countries to support UN peacekeeping. France is a European country that has long performed well in peacekeeping contributions. On the one hand, France is a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and it has assumed the responsibility of maintaining world peace. On the other hand, France has historically been inextricably linked with African countries, especially with its former colonies. France itself, therefore, has a strong need to ensure stability of the situation in Africa, and because many United Nations peacekeeping operations take place in Africa, naturally France will attach great importance to it.

India's contribution to UN peacekeeping has long ranked among the top 5 in the world. India was one of the earliest countries in the world to participate in UN peacekeeping, and it has always been very active. Some statistics show that India has sent more than 180,000 people to UN peacekeeping operations, making it one of the countries with the largest number of personnel sent to peacekeeping operations. India has also displayed its own characteristics and innovations in participating in UN peacekeeping. For example, in 2007, India became the first country to send an all-female peacekeeping team to a UN peacekeeping operation. Because India has been involved in UN peacekeeping for a long time and has participated in more peacekeeping operations, and because some peacekeeping operations are very dangerous, there has been a relatively large number of casualties in India’s peacekeeping operations. Statistics show that more than 160 Indian peacekeepers have died in peacekeeping operations.Footnote 14

China used to reject participation in UN peacekeeping operations, but now it has not only become an active participant, but also has made major contributions to participating in UN peacekeeping operations.Footnote 15 In 2012, China became a top ten country for the first time, and further rose to sixth place in 2018. Compared with many developed countries, China's participation in UN peacekeeping operations started relatively late, but the pace of development has been fast. In April 1990, the Chinese army sent five military observers to the UN Truce Supervision Organization. This was the beginning of China's participation in UN peacekeeping operations. As of 2020, China's peacekeeping operations will cover more than 20 countries and regions including Cambodia, Liberia, Congo (Kinshasa), Cyprus, Sudan, Lebanon, South Sudan, Mali and Central Africa. According to the data in the white paper "The Chinese Army's Participation in UN Peacekeeping Operations for 30 Years", the Chinese military has participated in 25 UN peacekeeping operations. As a key force in UN peacekeeping operations, China’s role includes six aspects: monitoring ceasefires, stabilizing the situation, protecting civilians, acting as security guards, supporting guarantees and spreading hope. Upholding the concept of "a community with a shared future for mankind", we can expect China to play a greater role in maintaining peace.

The above table shows that from 2010 to 2018, countries such as Laos, Somalia, South Sudan, Tuvalu and Comoros ranked last in terms of peacekeeping performance. These five countries have relatively small territories, relatively small populations, and relatively low levels of economic development. They are typical small countries. In countries such as Somalia and South Sudan, their domestic social order is relatively unstable, with internal ethnic, social and criminal problems emerging one after another. As their domestic problems are still very serious, it is difficult for these countries to make greater contributions to the UN peacekeeping cause. UN peacekeeping work requires financial and personnel technical support. Many small countries often do not have these capabilities and, therefore, cannot make a substantial contribution to UN peacekeeping.

From the data, we can find that the rankings of most countries are relatively stable, but there are also some countries whose rankings have experienced greater fluctuations from 2010 to 2018. For example, Italy's ranking has been gradually declining. Italy is a large European country, which formerly had colonized some countries in Africa, and is thus inextricably linked with Africa. And because Italy and the northern African countries belong to the countries along the Mediterranean Sea, in fact they are "across the sea" from each other, and as such Italy is affected by the impact of African refugees. However, in recent years, with the weakening of the Italian economy and the rise of a populist government in Italy, Italy's willingness and ability to participate in international affairs has gradually declined. During the same period, the rankings of the Philippines, Yemen, Albania, Nigeria and other countries dropped significantly. The reasons for the decline in the ranking of these countries are different. For example, Nigeria’s ranking dropped from 5th in 2010 to 48th in 2018. The reason for the decline in ranking is that Nigeria’s peacekeeping focus has always been on parts of West Africa. As the security situation in this region continues to improve, Nigeria has gradually reduced its peacekeeping forces.Footnote 16The ranking of the Philippines has gradually dropped from 31st in 2010 to 106th in 2018. The purpose of sending peacekeepers by the Philippines is to advance national interests and better participate in international military cooperation. Satisfying the needs of national interests is the primary reason. The Philippines tends to send peacekeepers to areas where there are more Filipinos overseas in accordance with the needs of the United Nations. This is because a large number of Filipino workers working overseas are sending money to their home country as an important source of income for the Philippines. Instability in some areas will affect the work of Filipino workers in these places and directly affect their remittances to their home country.Footnote 17

From 2010 to 2018, we found that Chad, Mauritania, Guyana, Cambodia, Gabon, Congo, Liberia and other countries have greatly increased their rankings. For example, Gabon’s ranking in peacekeeping rose from 145th in 2010 to 51st in 2018. Congo’s ranking in peacekeeping rose from 149th in 2010 to 74th in 2018. The countries that have risen sharply in these rankings are basically African countries and especially Central and West African countries. These African countries have increased their support for United Nations peacekeeping operations in the past few years and in particular have actively participated in peacekeeping operations in some areas of Africa. Among them, the most typical is the participation of countries such as Chad, Gabon, and Congo in the UN peacekeeping operations in the Central African Republic. The Central African Republic has been in a state of civil war since 2012. The government forces and the rebel coalition "Séléka" have been in a state of ongoing conflict.Footnote 18 Because the conflict in Central Africa still shows no sign of ending, these African countries may continue to be at the forefront of the ranking.

3.2.4 Regional Analysis

In 2018, the top 10 countries in the field of peacekeeping were the following: the United States, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Rwanda, India, China, Pakistan, Nepal, Egypt and Japan (Fig. 3). Among the top 10 countries, there is 1 American country, plus 6 Asian countries, and 3 African countries. No European country made the top 10. There are eight developing countries and two developed countries. This shows that the degree of economic development is not necessarily related to participation in UN peacekeeping. Both developed and developing countries have the opportunity and ability to play an important role in participating in UN peacekeeping. In fact, from the perspective of the top 10 selected countries, the contribution of developing countries to the cause of UN peacekeeping may be greater than that of developed countries.

The above-mentioned countries are able to rank highly in the field of peacekeeping because they have some common characteristics. First, these countries are generally concerned about the international and regional security situation. Needless to say, the United States has long played the role of “world police”. China and Japan are also very concerned about the international and regional security situation. China has always cherished a peaceful international and regional environment, because China's development cannot be separated from world peace. Second, the military capabilities of these countries are generally relatively strong. United Nations peacekeeping contributions are mainly personnel contributions and financial contributions. At present, personnel contributions are the core part. Sending troops and police to UN peacekeeping operations has certain requirements for the military capabilities of the sending country. United Nations peacekeeping operations are highly dangerous and peacekeepers are likely to be involved in local armed conflicts. United Nations peacekeepers sent by countries with stronger military capabilities can better deal with complex local political and military risks. Third, these countries aspire to play a more important role in international and regional affairs. The United States, China, India and Japan are all major countries with global influence, and have been very active in global governance. The United States and China are permanent members of the UN Security Council, and it is their responsibility to actively participate in peacekeeping operations. India and Japan have always sought to be among the permanent members of the UN Security Council, so they are very enthusiastic about participating in UN peacekeeping.

Next, we also classify countries according to their continents. These continents include Asia, Europe, North America, Latin America, Africa and Oceania. The ranking of each continent is obtained by calculating the average of the rankings of these countries. We drew a line chart to achieve a visual presentation to compare the differences in the contribution of each continent in peacekeeping (Fig. 4).

From the above figure, we can find that taking 2018 as an example, in terms of participating in UN peacekeeping, if we compare the average performance of countries on each continent, North American countries have contributed the most, followed by Asian and African countries and finally Latin American and Oceanian countries. North American countries only include the United States and Canada, which have performed very well in peacekeeping. African countries as a whole have also made relatively large contributions to peacekeeping. This is partly because many peacekeeping operations have taken place on African territory. Compared with other continents, Latin America and Oceania are at the bottom of the ranking. Latin American countries rank lower mainly because some island countries in Central America tend to have lower rankings; while Oceanian countries rank at the bottom because both the large countries in the region (Australia and New Zealand) and small Oceanian countries generally lag behind in their peacekeeping contribution rankings.

Asia In 2018, we found that the top 5 Asian countries are Bangladesh, India, China, Pakistan and Nepal, and the bottom countries are North Korea, Afghanistan, the Maldives, Micronesia and Laos. China and India are the top countries in the Asian region in terms of comprehensive national strength and are the two most populous countries among all developing countries. India was one of the earliest countries to participate in peacekeeping among all Asian countries, and it has consistently maintained this relatively high enthusiasm for participation. It is unexpected that Bangladesh ranks No. 1 in Asia. Bangladesh has a population of over 100 million, but its level of economic and social development is low, and nearly half of the population lives below the poverty line. Bangladesh has participated in UN peacekeeping work since the 1980s and has become the largest source of UN peacekeeping forces in this century.Footnote 19There are many reasons why Bangladesh actively participates in UN peacekeeping. On the one hand, this can greatly improve Bangladesh's regional and global reputation. On the other hand, Bangladesh can also receive a large amount of financial compensation. These funds can be used in all aspects of the country's construction in addition to paying for the soldiers killed and wounded in peacekeeping missions. Obtaining some financial assistance through participating in UN peacekeeping is a very important reason for developing countries to participate in peacekeeping.Footnote 20 Pakistan ranks highly in the field of peacekeeping, and even ranked second in the world in 2010. Pakistan and India are hostile to each other, and the foreign policies of the two countries are highly targeted at each other. Because India is actively participating in global peacekeeping operations to expand its influence, Pakistan also has the motivation to strengthen its influence in UN peacekeeping operations.Footnote 21Similar to Bangladesh, Pakistan's participation in UN peacekeeping operations is also motivated by financial returns. In the peacekeeping rankings of Asian countries, the countries that lag behind are often small and relatively closed countries. North Korea is a closed country and has not been involved in global and regional security affairs for a long time. Therefore, it is reasonable for it not to actively participate in the UN peacekeeping work. The Maldives, Micronesia and Laos are all small Asian countries, and their own capabilities limit their participation in UN peacekeeping operations.

Europe In 2018, we found that the top five European countries are France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy and Spain, and the bottom countries are Morocco, Andorra, North Macedonia and Albania. France and the United Kingdom are permanent members of the UN Security Council, and they themselves shoulder responsibility for maintaining global and regional security. Active participation in UN peacekeeping is a long-term foreign policy of France and the United Kingdom. Germany caused tremendous damage to global security in the Second World War. After the end of World War II, Germany adopted a diplomatic and security strategy of "hiding our power and biding our time" and did not actively participate in the work of the United Nations. It was not until the 1990s that Germany began to gradually participate in UN peacekeeping operations. Germany is a country with a large number of military and police contributions among developed countries, which notable as many developed countries are now gradually reducing the number of people they discharge. Germany is the fourth largest United Nations’ dues-paying country and has made a great financial contribution to UN peacekeeping.Footnote 22Another important reason why Germany has strengthened its contribution to UN peacekeeping is that it hopes to become a permanent member of the Security Council. At this point, the situation in Germany is similar to that of Japan and India. Britain once ranked higher than Germany in terms of peacekeeping, but in recent years Britain has begun to implement an "isolationist" policy. Britain’s contribution to peacekeeping is on a downward trend, which is basically consistent with Britain’s departure from the European Union. Morocco, Andorra, North Macedonia and Albania, which rank at the bottom, are all small European countries with a small population and a relatively small land area. They have long pursued a policy of partial security and are not actively participating in global governance.

North America The United States is a permanent member of the UN Security Council. It has long regarded itself as a "world policeman", and its active participation in UN peacekeeping is in line with this. On the other hand, the United States has a unique practical advantage in participating in UN peacekeeping. A large number of US defense funds are used to maintain various military bases outside the United States. According to incomplete statistics, the United States has more than 800 military bases in approximately 70 countries and regions. The existence of these military bases helps the United States keep abreast of the security situation and the latest trends in various countries and regions around the world.Footnote 23 These resources are a huge supporting force for the United States’ participation in UN peacekeeping. In recent years, the United States’ financial support for UN peacekeeping has been continuously increasing, while its contribution to UN personnel has gradually weakened. This is consistent with the performance of many other developed countries in UN peacekeeping. Canada is a developed country with a large area and a sparse population. Although it has a small population, it has always been a country with a global perspective. Canada participated in UN peacekeeping operations relatively early on. In the 1960s, participation in UN peacekeeping even became a part of Canada’s national identity, a responsibility and contribution that Canadians are proud of. Although the peacekeeping “fever” gradually subsided in Canada due to scandals and other reasons, Canada is still an important participant in UN peacekeeping.

Latin America In 2018, we found that the top three Latin American countries were Uruguay, Brazil and Argentina. The bottom countries are Grenada, Dominica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Haiti. Brazil and Argentina are the most important countries in South America, and it is not surprising that they are at the forefront of the UN peacekeeping rankings. Compared with Brazil and Argentina, Uruguay is a very small country. Uruguay has a population of just over 3 million, and its territory is the second smallest in Latin America, after Suriname. However, this relatively small country ranks much higher than Brazil and Argentina in terms of UN peacekeeping. There are many reasons why Uruguay ranks first in Latin America.

First of all, Uruguay has a relatively sound economic foundation, and its per capita GDP has long ranked first in Latin America. Second, Uruguay's peacekeeping capabilities have received assistance and support from the United States. Finally, Uruguay has a relatively long experience in participating in UN peacekeeping and has become one of the countries with the largest number of military and police contributions per capita to UN peacekeeping. The countries at the bottom are mainly small countries in Central America. These countries have small populations, low economic and social standards and severely inadequate national capabilities. Some of these countries are themselves destination countries for UN peacekeeping. A typical country in this regard is Haiti. For example, the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti was established in Haiti in 2004 and only ended in 2017. The lack of national capabilities restricts these countries from playing a greater role in UN peacekeeping.

Africa In 2018, we found that the top five African countries are Ethiopia, Rwanda, Egypt, Ghana and Tanzania, and the bottom countries are Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, South Sudan, Somalia and Comoros. Ethiopia is the most populous landlocked country in the world and the second most populous country in Africa. Ethiopia has participated in UN peacekeeping operations since the 1950s and has continued to do so to this day. At present, Ethiopia has become the country that has contributed the most to UN peacekeeping in terms of numbers. This is also the main reason why it can rank second in the world for its contribution to UN peacekeeping. Rwanda is a small country in Africa with a very small area. Rwanda experienced a terrible genocide in the 1990s, and is a country in which UN peacekeeping operations have also intervened. Rwanda has participated in UN peacekeeping operations since 2005. Although it started relatively late, it developed rapidly. Now Rwanda has become one of the countries that provides the most personnel support for UN peacekeeping—a very striking performance. Egypt began to participate in UN peacekeeping work in the 1960s, and today has become one of the countries with the largest number of military and police contributions. Egypt has participated in all of the UN peacekeeping projects in Africa, which shows that Egypt attaches great importance to its role in Africa’s security and stability. Ghana is a country in western Africa. Ghana began to participate in UN peacekeeping work in the 1970s, and has since increased the number of military and police dispatched, and as a result its contribution to peacekeeping has gradually increased. Tanzania is a country in eastern Africa. Tanzania has a large population, but its level of economic and social development is low. Nevertheless, Tanzania's ranking in the field of peacekeeping has been on the rise. The African countries at the bottom are Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, South Sudan, Somalia and Comoros. These countries have relatively small populations and relatively small land areas, and their economic and social development levels are at the middle and lower levels, even for Africa. Moreover, the internal social security and stability situation of some countries is severe, and there are many domestic contradictions. These factors limit their willingness and ability to participate in UN peacekeeping operations.

Oceania In 2018, we found that the top three countries in Oceania are Australia, Fiji and New Zealand. The bottom countries are Tuvalu, Palau and Tonga. Australia and New Zealand are the two largest countries in Oceania, and both are developed countries. These two countries were among the first countries to participate in the UN peacekeeping work, and have made great contributions to the development of the UN peacekeeping cause. However, in recent years, the rankings of these two countries in the field of peacekeeping have shown a downward trend. The main reason is that the number of military and police personnel sent by them has declined. In contrast, Fiji's ranking in the field of peacekeeping has improved significantly. Fiji is a small country in Oceania with a population of less than one million and a very small land area. Despite being a small country, Fiji has become a model for participation during its 40-year history of participating in UN peacekeeping. By per capita standards, Fiji has been the country with the most UN peacekeepers since the 1970s. Tuvalu, Palau and Tonga are all Pacific island countries, and their own national capabilities are not enough to make a significant contribution to UN peacekeeping, so they rank very low.

3.2.5 Conclusion

World peace is a common aspiration of the whole world and this is also inherent to the topic of promoting global justice. United Nations peacekeeping operations are an important means of maintaining peace and reducing wars, and they have achieved good results over the past few decades. At the same time, great changes have taken place in the types, methods and scope of countries participating in UN peacekeeping. Although the United States is the country that has contributed the most to participating in UN peacekeeping, the number of personnel sent is far lower than that of developing countries such as Ethiopia and Bangladesh. Developing countries are increasingly emerging as the backbone of UN peacekeeping operations. From the comparison of various continents, except for the outstanding performance of North America, the overall performance of other continents is almost the same. This shows that participation in peacekeeping is not necessarily related to a country’s wealth, population and geographic location. It may be related to the country’s will, the country’s interests and the country’s security environment. Today's world is still not at peace, and various regional conflicts occur one after another. UN peacekeeping operations will not only continue, but may also expand. This requires more countries to be willing to strengthen their support for UN peacekeeping operations. This support can be carried out in the form of increased peacekeeping funds or in the form of additional peacekeepers. No matter what form it takes, this is an important contribution to world peace and global justice.

3.3 Issue 3: Humanitarian Aid

3.3.1 Introduction

Humanitarian aid denotes the short-term assistance provided in response to natural disasters and emergencies. In recent years, international organizations are gradually building consensus about the guidelines and principles regarding humanitarian aid in both theoretical and practical respects. For example, the International Code of Medical Ethics asserts that doctors “are duty-bound to provide technically competent care, treat patients with compassion, and respect human dignity”, and the Geneva Conventions of 1949 proposed an international humanitarian law with the principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence.Footnote 24 Providing help to save lives, reduce suffering and maintain human dignity is a vital aspect of the global justice agenda. As a result, we included this issue into our global justice index and measure each country’s efforts to provide humanitarian aid by evaluating their financial contribution to global humanitarian affairs.

3.3.2 Dimensions and Indicators