Abstract

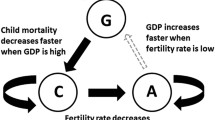

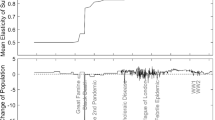

In every developed country, the economic transition from pre-industrial stagnation to modern growth was accompanied by a demographic transition from high to low fertility. Even though the overall pattern is repeated, there are large cross-country variations in the timing and speed of the demographic transition. What accounts for falling fertility during the transition to growth? To answer this question, this paper develops a unified growth model that delivers a transition from stagnation to growth, accompanied by declining fertility. The model is used to determine whether government policies that affect the opportunity cost of education can account for cross-country variations in fertility decline. Among the policies considered, education subsidies are found to have only minor effects, while accounting for child labor regulation is crucial. Apart from influencing fertility, the policies also determine the evolution of the income distribution in the course of development.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acemoglu, D., and J. A. Robinson. (2001). “A Theory of Political Transitions,” American Economic Review 91(4), 938–963.

Alam, I., and J. B. Casterline. (1984). Socio-Economic Differentials in Recent Fertility. World Fertility Survey Comparative Studies No. 33, Voorburg, Netherlands: International Statistical Institute.

Barro, R. J., and J. W. Lee. (1993). “International Comparisons of Educational Attainment,” Journal of Monetary Economics 32, 363–394.

Barro, R. J., and J. W. Lee. (2001). “Schooling Quality in a Cross Section of Countries,” Economica 68(272), 465–488.

Becker, G. S., and R. J. Barro. (1988). A “Reformulation of the Economic Theory of Fertility,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 53(1), 1–25.

Becker, G. S., K. M. Murphy, and R. Tamura. 1990. “Human Capital, Fertility, and Economic Growth,” Journal of Political Economy 98, 12–37.

Bloom, D. E., and J. G. Williamson. (1998). “Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia,” World Bank Economic Review 12(3), 419–455.

de la Croix, D., and M. Doepke. (2003). “Inequality and Growth: Why Differential Fertility Matters,” American Economic Review 93(4), 1091–1113.

Chesnais, J. C. (1992). The Demographic Transition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dahan, M., and D. Tsiddon. (1998). “Demographic Transition, Income Distribution, and Economic Growth,” Journal of Economic Growth 3, 29–52.

Deane, P., and W. A. Cole. (1969). British Economic Growth 1688–1959. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Deininger, K., and L. Squire. (1996). “A New Data Set Measuring Income Inequality,” World Bank Economic Review 10(3), 565–591.

Doepke, M. (2004). “Child Mortality and Fertility Decline: Does the Barro-Becker Model Fit the Facts?” Journal of Population Economics (forthcoming).

Doepke, M., and F. Zilibotti. (2004). The Macroeconomics of Child Labor Regulation. Unpublished Manuscript, UCLA and IIES.

Fernández-Villaverde, J. (2001). Was Malthus Right? Economic Growth and Population Dynamics. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Pennsylvania.

Galor, O., and O. Moav. (2002). “Natural Selection and the Origin of Economic Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4), 1133–1192.

Galor, O., and O. Moav. (2003). Das Human Kapital: A Theory of the Demise of the Class Structure. Unpublished Manuscript, Brown University and Hebrew University.

Galor, O., O. Moav, and D. Vollrath. (2003). Land Inequality and the Origin of Divergence and Overtaking in the Growth Process: Theory and Evidence. Unpublished Manuscript, Brown University and Hebrew University.

Galor, O., and A. Mountford. (2003). Trading Population for Productivity. Unpublished Manuscript, Brown University and Hebrew University.

Galor, O., and D. N. Weil. (1996). “The Gender Gap, Fertility, and Growth,” American Economic Review 86(3), 375–387.

Galor, O., and D. N. Weil. (2000). “Population, Technology, and Growth: From Malthusian Stagnation to the Demographic Transition and Beyond,” American Economic Review 90(4), 806–828.

Greenwood, J., and A. Seshadri. (2002). “The US Demographic Transition,” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 92(2), 153–159.

Hansen, G. D., and E. C. Prescott. (2002). “Malthus to Solow,” American Economic Review 92(4), 1205–1217.

Haveman, R., and B. Wolfe. (1995). “The Determinants of Children's Attainments: A Review of Methods and Findings,” Journal of Economic Literature 33, 1829–1878.

Hazan, M., and B. Berdugo. (2002). “Child Labor, Fertility, and Economic Growth,” The Economic Journal 112(482), 810–828.

Horrell, S., and J. Humphries. (1995). “The Exploitation of Little Children: Child Labor and the Family Economy in the Industrial Revolution,” Explorations in Economic History 32, 485–516.

International Labor Organization (ILO). Year Book of Labour Statistics, Various editions. Geneva: ILO.

Jones, C. I. (2001). “Was an Industrial Revolution Inevitable? Economic Growth over the Very Long Run,” Advances in Macroeconomics 1(2), Article 1.

Jones, E. F. (1982). Socio-Economic Differentials in Achieved Fertility. World Fertility Survey Comparative Studies No. 21, Voorburg, Netherlands: International Statistical Institute.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S. (2002). “Does the Mortality Decline Promote Economic Growth?” Journal of Economic Growth 7(4), 411–439.

Kögel, T., and A. Prskawetz. (2001). “Agricultural Productivity Growth and the Escape from the Malthusian Trap,” Journal of Economic Growth 6, 337–357.

Knowles, J. (1999). Can Parental Decisions Explain US Income Inequality? Working paper, University of Pennsylvania.

Kremer, M., and D. Chen. (2002). “Income Distribution Dynamics with Endogenous Fertility,” Journal of Economic Growth 7(3), 227–258.

Kuznets, S. (1955). “Economic Growth and Income Inequality,” American Economic Review 45, 1–28.

Lagerlöf, N.-P. (2003). “Gender Equality and Long-Run Growth,” Journal of Economic Growth 8(4), 403–426.

Lee, R. D., and R. S. Schofield. (1981). “British Population in the Eighteenth Century,” in Floud, R., and D. McCloskey (eds.), The Economic History of Britain since 1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maddison, A. (1991). Dynamic Forces in Capitalist Development: A Long-Run Comparative View. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Margo, R. A., and T. A. Finegan. (1996). “Compulsory Schooling Legislation and School Attendance in Turn-of-the-Century America: A 'Natural Experiment' Approach,” Economics Letters 53, 103–110.

Moav, O. (2005). “Cheap Children and the Persistence of Poverty,” The Economic Journal (forthcoming).

Morand, O. F. (1999). “Endogenous Fertility, Income Distribution, and Growth,” Journal of Economic Growth 4(3), 331–349.

Nardinelli, C. (1980). “Child Labor and the Factory Acts,” Journal of Economic History 40(4), 739–755.

Ngai, L. R. (2000). Barriers and the Transition to Modern Growth. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Pennsylvania.

Park, Y.-B., D. R. Ross, and R. H. Sabot. (1996). “Educational Expansion and the Inequality of Pay in Brazil and Korea,” in Birdsall, N., and R. H. Sabot (eds.), Opportunity Forgone: Education in Brazil. Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, D.C.

Preston, S. H., N. Keyfitz, and R. Schoen. (1972). Causes of Death: Life Tables for National Populations. New York: Seminar Press.

Rosenzweig, M. R., and R. Evenson. (1977). “Fertility, Schooling, and the Economic Contribution of Children in Rural India: An Econometric Analysis,” Econometrica 45(5), 1065–1079.

Tamura, R. (2002). “Human Capital and the Switch from Agriculture to Industry,” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 27, 207–242.

United Nations. (1995). Women's Education and Fertility Behavior. New York: United Nations.

Veloso, F. A. (1999). Income Composition, Endogenous Fertility and the Dynamics of Income Distribution. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Chicago.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doepke, M. Accounting for Fertility Decline During the Transition to Growth. Journal of Economic Growth 9, 347–383 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEG.0000038935.84627.e4

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEG.0000038935.84627.e4