Abstract

The ice arches that usually develop at the northern and southern ends of Nares Strait play an important role in modulating the export of Arctic Ocean multi-year sea ice. The Arctic Ocean is evolving towards an ice pack that is younger, thinner, and more mobile and the fate of its multi-year ice is becoming of increasing interest. Here, we use sea ice motion retrievals from Sentinel-1 imagery to report on the recent behavior of these ice arches and the associated ice fluxes. We show that the duration of arch formation has decreased over the past 20 years, while the ice area and volume fluxes along Nares Strait have both increased. These results suggest that a transition is underway towards a state where the formation of these arches will become atypical with a concomitant increase in the export of multi-year ice accelerating the transition towards a younger and thinner Arctic ice pack.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

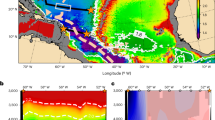

Along Nares Strait, the channel that separates north Greenland from Ellesmere Island, please refer to Fig. 1 for place names in the region of interest, ice arches typically form each winter at both its northern and southern ends1,2. The formation of either of these arches results in the cessation of ice transport from the Lincoln Sea southwards towards Baffin Bay and the subpolar North Atlantic1,3. The oldest and thickest sea ice in the Arctic is found to the north of Nares Strait4,5,6 and as a result, the formation of these arches, as well as ones that form along channels through the nearby Canadian Arctic Archipelago7 (CAA), contribute to the cessation of the transport of this important ice-class out of the Arctic1,8. For the period 1997–2009, the southern arch formed most winters while the northern arch formed during ~50% of the winters2,9. During the winter of 2007, neither arch formed resulting in annual ice area and volume fluxes that were twice as large as the corresponding climatological means over 1997–20092.

The cessation of ice transport down Nares Strait contributes to the formation of the Arctic’s largest and most productive polynya, the North Water, at its southern end in the vicinity of Smith Sound10,11. In addition, climate models suggest that the area to the north of the Lincoln Sea will be the last to lose its perennial ice cover12,13 thus providing an important refuge, referred to as the Last Ice Area, for ice-dependent species14,15. The stability of these arches is a function of the thickness of the ice16 and there is a concern that the thinning of the Arctic ice pack may negatively impact their stability resulting in an acceleration in the loss of multi-year ice from the Arctic as well as impacting the ecosystems of the North Water Polynya and the Last Ice Area2,14.

We show that in addition to the previously identified early collapse of the northern ice arch in May 201717, this arch failed to develop during the winters of 2018 and 2019. In contrast, we report that the southern ice arch was only present for a short period of time during the winter of 2018. The winter of 2019, like the previously documented winter of 20072, was one in which no ice arches formed along Nares Strait. We furthermore show that there has been a recent increase in both the ice area and ice volume flux along Nares Strait as compared to the period from 1997 to 20092. Over the period for which we have observations, 1997–2019, there has been a statistically significant trend towards shorter duration of ice arch formation each winter.

Results

The May 2017 Collapse

During the winter of 2017, the northern ice arch collapsed in early May with thin ice in the Lincoln Sea hypothesized as contributing to the earliest collapse in the admittedly short record2,17. Fig. 2 shows the sea ice state of the northern Nares Strait and southern Lincoln Sea region during the period of the arch collapse from Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery. Also shown are sea ice motion vectors, derived by feature tracking of sequential pairs of Sentinel-1 images using a technique described in the Methods Section18. On May 8 (Fig. 2a), the arch can be seen as the boundary between the thick multi-year ice to its north and the recently formed thin ice to its south. No significant ice motion was observed on this date, maximum ice velocities <1 km/day, indicating that the arch was stable. Two days later on May 10 (Fig. 2b), the arch had begun to collapse, as evidenced by southward movement of ice across the flux gate with maximum velocities ~5 km/day. Over the next 4 days (Fig. 2c, d), the arch fully collapsed resulting in ice velocities as large as 25 km/day that transported multi-year ice floes southwards into northern Nares Strait.

Ice Area Flux

Using the Senintel-1 sea ice motion data across the flux gate indicated in Figs. 1 and 2, for the period of its availability, 2016–2019, it is possible to derive ice area flux data time series for Nares Strait that are similar to those reported for the 13-year period from 1997 to 20092. Please refer to the Methods Section for more information. Fig. 3 shows this time series with the sign convention that southward/northward ice motion results in a positive/negative ice area flux. Although the flux is on average positive, it is highly variable in time with frequent brief instances where the flux is negative, i.e., northward ice motion. This high-frequency variability has been noted previously with acoustic Doppler current profiler data11 from the region and is consistent with the regional winds that show frequent reversals in direction17,19.

The vertical solid red lines represent the best available estimates for the onset of the stoppage of ice motion along Nares Strait during 2017 and 2018 with the dashed red lines representing the best available estimate of the end of the stoppage during 2017 and 2018. The average ice area flux over various periods of interest are indicated by the blue lines. All data based on Sentinel-1 satellite-derived sea ice motion vectors.

A noticeable reduction in the magnitude of the ice area flux occurred around January 30, 2017 (Fig. 3). Sentinel-1 imagery, not shown, indicated that the reduction of the ice area flux was associated with the formation of the northern ice arch. Low ice area fluxes persisted until the collapse of the ice arch around May 10 (Fig. 2). For the period from September 1 2016 to January 30, 2017, the average ice area flux was 366 km2 day−1, while for period of the 2017 ice arch, it was 31 km2 day−1. After the collapse, the magnitude of the ice area flux was again large and highly variable until the end of March 2018 when a large reduction in magnitude also occurred. For the period of May 11 2017 to March 28, 2018, the average ice area flux was 496 km2 day−1. After March 28, 2018, the magnitude of the ice area flux remained small, an average of 46 km2 day−1, until late June 2018 when another transition to large magnitude and highly variable ice area flux occurred that persisted until the end of August 2019. For this period, the average ice area flux was 265 km2 day−1.

Figure 2 and previous work17 indicate that the period of reduced ice area flux during 2017 was the result of the formation and subsequent collapse of the northern ice arch. MODIS true color and Sentinel-1 imagery during the 2018 period of low ice area flux, an example of which is shown in Fig. 4, show no evidence of a northern ice arch along with the presence of multi-year ice along Nares Strait with a southern ice arch along Smith Sound. In 2019, we interpret the absence of a period of reduced ice area flux (Fig. 3) as evidence that neither type of ice arch formed along Nares Strait during this winter.

There were reports, based on visible satellite imagery, of the existence of the northern ice arch during the winter of 2019 and its subsequent collapse in March20. Indeed Sentinel-1 imagery (Fig. 5) does indicate the presence of an arch-like structure during the winter of 2019. However the associated ice-motion data indicates, in agreement with the ice area flux data (Fig. 3), that this structure was unstable and never resulted in the cessation of ice motion along Nares Strait.

Sentinel-1 SAR satellite images and derived sea ice motion vectors (km day-1) on: a January 14 2019 at 18:55 GMT GMT; b February 7 2019 at 18:55GMT; c February 19 2019 at 18:55 GMT; and d March 27 2019 at 12:33 GMT. The southern Lincoln Sea flux gate used to calculate the ice area flux is shown in red.

These conclusions are consistent with the monthly mean sea ice concentration based on passive microwave data from AMSR-E and AMSR221. The climatology for June (Fig. 6a) indicates that the ice cover over the Lincoln Sea is typically close to 100%, while that along Nares Strait is lower at 60-80%. To the south of Nares Strait, over the North Water, ice cover is close to 0%. During June 2017 (Fig. 6b), after the collapse of the northern ice arch, ice cover along Nares Strait is lower than the climatology with open water along the eastern coast of the strait and higher ice concentrations to the west that is consistent with coastal downwelling and southward ice and ocean velocities associated the climatological northerly winds22,23,24. In contrast, during June 2018 (Fig. 6c) 100% ice cover was present along much of Nares Strait to the north of Smith Sound, a result consistent with a cessation of ice motion as a result of the presence of a southern ice arch. The situation during June 2019 (Fig. 6d) is similar to that during June 2017 and again is consistent with southward ice transport.

Ice Volume Flux

The combination of the ice area flux data for 2016–2019 presented herein with a previous record from 1997 to 20092, allows one to examine the changes in the characteristics for the annual mean, defined over the period from September 1 to August 31 of the following year, sea ice transport along Nares Strait over the past 23 years. Annual mean ice thicknesses from the PIOMAS sea ice reanalysis25,26 are also used to derive ice volume fluxes. In the vicinity of Nares Strait, PIOMAS has a horizontal resolution of approximately 20 km26. PIOMAS has a recognized tendency to underestimate the thickness of thick ice and overestimate the thickness of thin ice25,27,28. Figure 7 compares the monthly mean sea ice thickness for two satellite-based retrievals, AWI CryoSat229, and UCL CryoSat230, against the monthly mean PIOMAS sea ice thickness data for a representative area of the Lincoln Sea shown in Fig. 1. The agreement between PIOMAS and the retrievals is consistent with previous work12,25,28.

The annual mean ice area flux time series (Fig. 8a) indicates that the average over the 2017–2019 exceeded the largest flux previously observed, that occurred during 2007 when no arches formed2. Furthermore, over the period 1997–2009 the average annual mean ice area flux was 42,000 km2 while over 2017–2019 it was over twice as large at 86,000 km2. Arctic sea ice is becoming thinner, this is also true for the Lincoln Sea where the PIOMAS annual mean ice thickness has decreased from 3.7 m during the period 1997–2009 to 2.4 m recently with an uncertainty of ±0.75 m (Fig. 8b). The ice volume flux can be estimated from the product of the ice area flux and Lincoln Sea ice thickness. This time series is shown in Fig. 8c. Unlike the situation that occurred for the ice area flux, the ice volume flux during 2007 was higher than that for any of the years from 2017 to 2019. This is the result of the recent thinning of the Lincoln Sea ice cover. However, the average annual ice volume flux over the period 2017–2019 was nevertheless ~70% larger, at 190 ± 55 km3, than that for the period 1997–2009, 112 ± 16 km3.

a The annual mean ice area flux (103 km2) through the southern Lincoln Sea flux gate. b The annual mean sea ice thickness (m) over the southern Lincoln Sea estimated from PIOMAS data. c The annual mean ice volume flux (km3) through the southern Lincoln Sea flux gate. The data in red is from Kwok et al study with the data in blue from this study. Means over the period of the two data sets (1997–2009) and (2016–2019) are shown with dashed lines. Annual means defined from Sept 1 to Aug 31. In b and c, error bars are included based on the uncertainty in ice thickness derived from the comparison with CryoSat2 data shown in Fig. 7 (see Methods). As discussed in the Methods Section, the uncertainty in ice area flux is negligible on annual time scales.

In addition to the aforementioned changes with time, all three-time series shown in Fig. 8 indicates the presence of inter-annual variability that may be associated with variability in sea ice motion across the central Arctic that has been shown to impact sea ice thickness in the Lincoln Sea14. We note that the difference in the mean ice thickness and ice volume flux between the two periods under investigation exceeds the corresponding uncertainty suggesting that the changes are robust.

Ice Arch Stability

Finally, we assess the time evolution of the stability of the Nares Strait ice arches by combining their duration as previously reported2 with that derived for 2016–2019 from the ice area flux data presented herein. Figure 9 presents the results for the combined duration of both the northern and southern ice arches with a significance test described in the Methods Section. Similar results were obtained when the two arches were considered separately. Over time, the tendency for shorter duration arches is evident with a trend of approximately −7 days/year (p < 0.01).

Discussion

The largest loss of Arctic sea ice occurs through Fram Strait31, on the east side of north Greenland, with typical annual ice area fluxes on the order of 900,000 km2. Although there has been a similar recent increase in ice area flux through Fram Strait, again indicative of a more mobile ice pack, there has been no corresponding increase in ice volume flux31. Given that the ice volume flux is the product of the ice area flux and the ice thickness, this implies that for the Nares Strait region the increase in ice area flux exceeds the reduction in thickness with the two compensating more or less for the Fram Strait region.

Recent work indicates that ice motion in the Last Ice Area, that includes the Lincoln Sea, is increasing at twice the rate as the entire Arctic Ocean14. In addition, a number of theoretical16,32 and observational8,17 studies have proposed that the stability of the Nares Strait ice arches decreases with thinning ice cover. These results are consistent with those presented herein all of which provide additional evidence of the changing nature of the Arctic as we transition to a thinner more mobile ice pack. Results of this study also highlight that with continued Arctic warming, ice arch stability in Nares Strait as well as throughout the adjacent CAA will decrease resulting in more frequent transport of Arctic Ocean multi-year to southerly latitudes7, that will have negative implications for the maritime industry33,34 as well as impacting food security and other traditional activities for indigenous communities in the Arctic35.

The current configuration of the North Water Polynya, as a latent heat polynya, depends on the presence of the Nares Strait ice arches36 to restrict the southward flux of thick multi-year ice along Nares Strait. This allows the strong winds and ocean currents that occur in the vicinity of Smith Sound23,37 to advect thin ice away allowing the polynya to form. It follows that a weakening of the Nares Strait ice arches may impact the North Water Polynya leading to regional changes in primary and secondary production that will be felt throughout the entire food chain

Methods

Ice Area Flux

Annual (September to August) ice area flux through Nares Strait for 2016–2019 was determined using an established technique2,18,38. First, sea ice motion from each sequential pair of Sentinel-1 imagery (~0.5 to 1-day time separation) was determined using the Komarov and Barber tracking algorithm39. Sea ice motion was then interpolated to a 30 km buffer region surrounding the gate and sampled at 5 km intervals across. Considering that ice rapidly deforms as it is being funneled through Nares Strait we placed our gate farther north of Nares Strait than has been done previously2 to facilitate improved motion detection. The ice area flux (F) was calculated using: \(F = {\sum} {c_iu_i\Delta x}\) where ci is the ice concentration obtained from the closest Canadian Ice Service ice chart40 to the Sentinel-1 image date, ui is the ice speed normal to the flux gate at the ith location and Δx is the spacing along the gate (5 km). If we assume that the errors of the sea ice motion samples are additive, unbiased, uncorrelated, and normally distributed, then the uncertainty in ice area flux across the gate (σf) can be determined using the following equation: \(\sigma _f = \sigma _eL\left( {\sqrt {N_s} } \right)^{ - 1},\)where, σe is the error in ice motion of 0.43 km/day determined previously39, L is the width of the gate and Ns is the number of samples across the gate. For L=139 km and Ns=27 the uncertainty in ice area flux at our gate is ~±12 km2/day. On monthly or annual timescales, the uncertainty is close to zero.

Statistical Significance

Many geophysical time series are characterized by red-noise arising from temporal autocorrelation that results in power spectra that have elevated power at low frequencies41,42. To account for this characteristic, which if unaccounted for may result in an overestimation of the significance42, we use is a non-parametric Monte Carlo technique where a large number, in this instance 100,000, of synthetic time series that share the same power spectrum as the original time series are generated. The distribution of the trends of these synthetic time series are used to estimate the significance of the trend in the underlying time series. By sharing the same spectral characteristics, one has greater confidence that they share the same background variability and one is not introducing a bias into the assessment of the statistical significance of the trend. To generate the synthetic time series, the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the underlying time series is calculated. For each individual synthetic time series, the phase of the Fourier components are randomized and then the Inverse FFT is calculated41.

Data availability

Sentinel-1 SAR imagery is available from the Copernicus Open Access Hub at: http://scihub.copernicus.eu. AMSRE/2 sea ice concentration data is available from the University of Bremen at: https://seaice.uni-bremen.de/. The PIOMAS sea ice thickness data is available from the Polar Sciences Center at the University of Washington at: http://psc.apl.uw.edu/research/projects/arctic-sea-ice-volume-anomaly/. The AWI CryoSat2 sea ice thickness data is available from the Alfred Wegener Institute at: http://data.meereisportal.de/data/cryosat2/version2.2/. The UCL CryoSat2 sea ice thickness data is available from the University College London at: http://www.cpom.ucl.ac.uk/csopr/seaice.html. Moore43 provides the ice area flux time series derived from the Seninel-1 data.

References

Kwok, R. Variability of Nares Strait ice flux. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32 (2005).

Kwok, R., Toudal Pedersen, L., Gudmandsen, P. & Pang, S. S. Large sea ice outflow into the Nares Strait in 2007. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L03502 (2010).

Kozo, T. L. The hybrid polynya at the northern end of Nares Strait. Geophys. Res. Lett. 18, 2059–2062 (1991).

Bourke, R. H. & Garrett, R. P. Sea ice thickness distribution in the Arctic Ocean. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 13, 259–280 (1987).

Kwok, R. Arctic sea ice thickness, volume, and multiyear ice coverage: losses and coupled variability (1958–2018). Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 105005 (2018).

Maslanik, J., Stroeve, J., Fowler, C. & Emery, W. Distribution and trends in Arctic sea ice age through spring 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL047735 (2011).

Melling, H. Sea ice of the northern Canadian Arctic Archipelago. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 107, 2-1-2-21 (2002).

Kwok, R. et al. Thinning and volume loss of the Arctic Ocean sea ice cover: 2003–2008. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 114 (2009).

Ryan, P. A. & Münchow, A. Sea ice draft observations in Nares Strait from 2003 to 2012. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 122, 3057–3080 (2017).

Barber, D. G., Hanesiak, J. M., Chan, W. & Piwowar, J. Sea‐ice and meteorological conditions in Northern Baffin Bay and the North Water polynya between 1979 and 1996. Atmosphere-Ocean 39, 343–359 (2001).

Münchow, A. Volume and Freshwater Flux Observations from Nares Strait to the West of Greenland at Daily Time Scales from 2003 to 2009. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 46, 141–157 (2016).

Laliberté, F., Howell, S. E. L. & Kushner, P. J. Regional variability of a projected sea ice-free Arctic during the summer months. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 256–263 (2016).

Sou, T. & Flato, G. Sea Ice in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago: modeling the past (1950–2004) and the future (2041–60). J. Clim. 22, 2181–2198 (2009).

Moore, G.W.K., Schweiger, A., Zhang, J. & Steele, M. Spatiotemporal variability of Sea Ice in the Arctic’s Last Ice Area. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 11237–11243 (2019).

Pfirman, S., Tremblay, B., Newton, R. & Fowler, C. The last Arctic sea ice refuge. AGUFM 2010, C43E–C40592 (2010).

Hibler, W., Hutchings, J. & Ip, C. Sea-ice arching and multiple flow states of Arctic pack ice. Ann. Glaciol. 44, 339–344 (2006).

Moore, G. W. K. & McNeil, K. The Early Collapse of the 2017 Lincoln Sea Ice Arch in Response to Anomalous Sea Ice and Wind Forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 8343–8351 (2018).

Howell, S. E. et al. Recent changes in the exchange of sea ice between the Arctic Ocean and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 118, 3595–3607 (2013).

Samelson, R.M., Agnew, T., Melling, H. & Münchow, A. Evidence for atmospheric control of sea‐ice motion through Nares Strait. Geophys. Res. Letters 33 (2006).

Hansen, K. Ice Arch Crumbles Early, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/145232/ice-arch-crumbles-early (2019).

Spreen, G., Kaleschke, L. & Heygster, G. Sea ice remote sensing using AMSR-E 89-GHz channels. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 113, n/a–n/a (2008).

Dumont, D., Gratton, Y. & Arbetter, T. E. Modeling Wind-Driven Circulation and Landfast Ice-Edge Processes during Polynya Events in Northern Baffin Bay. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 40, 1356–1372 (2010).

Moore, G. W. K. & Våge, K. Impact of model resolution on the representation of the air–sea interaction associated with the North Water Polynya. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 144, 1474–1489 (2018).

Münchow, A. & Melling, H. Ocean current observations from Nares Strait to the west of Greenland: Interannual to tidal variability and forcing. J. Mar. Res. 66, 801–833 (2008).

Schweiger, A. et al. Uncertainty in modeled Arctic sea ice volume. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 116, n/a–n/a (2011).

Zhang, J. & Rothrock, D. A. Modeling Global Sea Ice with a Thickness and Enthalpy Distribution Model in Generalized Curvilinear Coordinates. Monthly Weather Rev. 131, 845–861 (2003).

Howell, S. E., Laliberté, F., Kwok, R., Derksen, C. & King, J. Landfast ice thickness in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago from observations and models. Cryosphere 10, 1463–1475 (2016).

Lindsay, R. & Schweiger, A. Arctic sea ice thickness loss determined using subsurface, aircraft, and satellite observations. Cryosphere 9, 269–283 (2015).

Ricker, R., Hendricks, S., Helm, V., Skourup, H. & Davidson, M. Sensitivity of CryoSat-2 Arctic sea-ice freeboard and thickness on radar-waveform interpretation. Cryosphere 8, 1607–1622 (2014).

Tilling, R. L., Ridout, A. & Shepherd, A. Estimating Arctic sea ice thickness and volume using CryoSat-2 radar altimeter data. Adv. Space Res. 62, 1203–1225 (2018).

Smedsrud, L. H., Halvorsen, M. H., Stroeve, J. C., Zhang, R. & Kloster, K. Fram Strait sea ice export variability and September Arctic sea ice extent over the last 80 years. Cryosphere 11, 65–79 (2017).

Rallabandi, B., Zheng, Z., Winton, M. & Stone, H. A. Formation of sea ice bridges in narrow straits in response to wind and water stresses. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 122, 5588–5610 (2017).

Barber, D. et al. Increasing mobility of high Arctic sea ice increases marine hazards off the east coast of Newfoundland. Geophys. Research Letters (2018).

Haas, C. & Howell, S. E. Ice thickness in the Northwest Passage. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7673–7680 (2015).

Huet, C. et al. Food insecurity and food consumption by season in households with children in an Arctic city: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 17, 578 (2017).

Ingram, R. G., Bâcle, J., Barber, D. G., Gratton, Y. & Melling, H. An overview of physical processes in the North Water. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 49, 4893–4906 (2002).

Shroyer, E. L., Samelson, R. M., Padman, L. & Münchow, A. Modeled ocean circulation in Nares S trait and its dependence on landfast‐ice cover. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 120, 7934–7959 (2015).

Kwok, R. Exchange of sea ice between the Arctic Ocean and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33 (2006).

Komarov, A. S. & Barber, D. G. Sea ice motion tracking from sequential dual-polarization RADARSAT-2 images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 52, 121–136 (2013).

Tivy, A. et al. Trends and variability in summer sea ice cover in the Canadian Arctic based on the Canadian Ice Service Digital Archive, 1960–2008 and 1968–2008. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 116 (2011).

Rudnick, D. L. & Davis, R. E. Red noise and regime shifts. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanographic Res. Pap. 50, 691–699 (2003).

Santer, B. D. et al. Statistical significance of trends and trend differences in layer-average atmospheric temperature time series. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 105, 7337–7356 (2000).

Moore, G.W.K. Nares Strait Ice Area Flux, https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/WRGX0K, (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Copernicus Programme of the European Space Agency for access to the Sentinel-1 SAR imagery. All figures were created by the authors using the MATLAB software system. GWKM would like to acknowledge funding support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.W.K.M. conceived the study. S.E.L.H. and M.B. analyzed the SAR imagery and generated the ice motion data. G.W.K.M., S.E.L.H., M.B, X.X., and K.M. contributed to the analysis and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Walt Meier, Andreas Münchow and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, G.W.K., Howell, S.E.L., Brady, M. et al. Anomalous collapses of Nares Strait ice arches leads to enhanced export of Arctic sea ice. Nat Commun 12, 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20314-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20314-w

This article is cited by

-

Vaccination with a combination of STING agonist-loaded lipid nanoparticles and CpG-ODNs protects against lung metastasis via the induction of CD11bhighCD27low memory-like NK cells

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2024)

-

DANCE: a deep learning library and benchmark platform for single-cell analysis

Genome Biology (2024)

-

Powerful and accurate detection of temporal gene expression patterns from multi-sample multi-stage single-cell transcriptomics data with TDEseq

Genome Biology (2024)

-

Applications of peptides in nanosystems for diagnosing and managing bacterial sepsis

Journal of Biomedical Science (2024)

-

Anchor Clustering for million-scale immune repertoire sequencing data

BMC Bioinformatics (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.