Key Points

-

Evaluates the reliability of information of orthodontic practice websites.

-

Outlines the GDC regulations on ethical advertising.

-

Stresses that practice websites should not mislead the public and quality of information presented needs to be improved.

Abstract

Objective To evaluate orthodontic practice websites for the reliability of information presented, accessibility, usability for patients and compliance to General Dental Council (GDC) regulations on ethical advertising.

Setting World Wide Web.

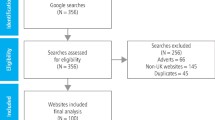

Materials and methods The term 'orthodontic practice' was entered into three separate search engines. The 30 websites from the UK were selected and graded according to the LIDA tool (a validated method of evaluating healthcare websites) for accessibility, usability of the website and reliability of information on orthodontic treatment. The websites were then evaluated against the GDC's Principles for ethical advertising in nine different criteria.

Results On average, each website fulfilled six out of nine points of the GDC's criteria, with inclusion of a complaints policy being the most poorly fulfilled criteria. The mean LIDA score (a combination of usability, reliability and accessibility) was 102/144 (standard deviation 8.38). The websites scored most poorly on reliability (average 43% SD 11.7), with no single website reporting a clear, reliable method of content production. Average accessibility was 81% and usability 73%.

Conclusions In general, websites did not comply with GDC guidelines on ethical advertising. Furthermore, practitioners should consider reporting their method of information production, particularly when making claims about efficiency and speed of treatment in order to improve reliability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and objectives:

As of 2013, two billion people have access to the Internet.1 Around 34.5% of dental patients have either researched their condition or treatment online.2 Today dental practices use the Internet and their own websites to market their services to the general public. The public in turn can use these websites to find out a little more about the practice or their clinician and the treatments that they provide. Websites can be published by almost any person or institution, and medical information websites in general are rarely the subject of peer review.1,3 Patients may therefore find it difficult to discern between websites with valid information.3,4,5,6,7

A survey conducted in 2007 found that many people preferred to initially view healthcare information online rather than seek the view of a qualified medical professional.5 Although the online information did not replace the interaction with a medical professional, information from the internet was found to have an impact on discussions with medical professionals regarding potential treatment options.5 This has led to speculation that information online, which is often not peer reviewed and may reflect commercial interest rather that the best course of treatment for the patient, could lead to inaccurate or inappropriate perceptions of healthcare modalities among members of the general public.1,3,5

This is of concern as 50% of dentists say patients have discussed information relevant to their treatment that they have found online,8 and over a third of dental patients have researched their condition or procedure online. Two thirds of patients who research health information online claim that it has an effect on decisions regarding their treatment.9 Inaccurate information from the internet can lead to a disagreement on a course of treatment between a clinician and patient.10

In March 2012 the General Dental Council (GDC) published the Principles of ethical advertising11 – a guideline for dental clinicians' use during the creation of promotional material. This was as a result of an initial consultation in 2010 that carried concerns around the methods of advertising that were being used by some practioners.12 Of all cases that reached the Fitness to Practise Panel at the GDC between April 2009-April 2010 10.76% were related to advertising. The lack of clear guidance was believed to have left a situation where patients may have been misled, particularly with the use of dentist's titles, qualifications and descriptions.13

Research commissioned by the GDC in 2009 demonstrated confusion by members of the public regarding the use of specialist titles among dental professionals.12 'Specialist sounding titles' were believed by members of the public to be equivalent to that of a specialist, and although a 'specialist' was seen to be an important title, few members of the public were sure what this actually meant. The importance of accurate use of titles is enshrined in law, with the Dentists Act of 1984 making it an offense for a dentist to use a title or qualification other than the one they are registered with the GDC.12

Complaints about websites generally focused on the use of inappropriate terms or a lack of explanation around specific claims made on these sites.12 In all, the implication of a lack of clear guidance surrounding these issues was that there was a risk that members of the public could be misled with respect to the level of expertise and quality of clinical work that could be provided.13

Against this backdrop a guidance document was produced by the GDC.12,13 Many of the basic principles were based upon the European Union (EU) Manual of dental practice, a document produced to help aid the movement of dental professionals throughout the EU.14 The GDC document has guidance on websites, advertising services, specialist titles and honorary degrees and memberships.11

To date, the authors have found few papers that review the quality of dental practice websites. Nichols et al. published The quality and content of dental practice websites in 2011.15 This paper demonstrated that few dental practice websites complied with regulations at the time.

The LIDA instrument is one of many tools that have been used to assess the quality of healthcare websites. It has previously been used to measure the quality of information presented online about orthodontic extractions,1 pain during orthodontic treatment,16 colorectal cancer,17 and vascular surgery.18 The tool itself is composed of a questionnaire in three separate sections, examining the websites usability, reliability and accessibility.

The aim of this paper is to assess the compliance of orthodontic practice websites to a relatively new set of guidance notes, as well as the websites quality and reliability using the LIDA instrument.19

Design, materials and method

Search engines

The three most used online search engines in the UK were selected for this study. These included Google, Yahoo and Ask.20 UK specific (that is, www.google.co.uk, www.yahoo.co.uk and www.ask.co.uk) websites were used for the study, in order to help reduce results from outside of the UK.

The term 'orthodontic practice' was entered into each of the engines and the top ten unique websites in each engine were analysed according to a Principles of ethical advertising-based criteria and the LIDA instrument. The searches were conducted in order of the search engines popularity, with the Google search being analysed first, Yahoo second and Ask last. Websites that had been analysed as a part of a previous search were skipped and the next website reviewed. Websites of mixed practices (that is, practices that were not entirely based in orthodontics) were excluded. A total of 30 websites were analysed. Websites that were not based within the UK were omitted from the study.

GDC criteria

The websites were reviewed thoroughly, and compared to nine aspects of the principles of ethical advertising document. Areas reviewed included:

-

Name and address of practice

-

Contact details of practice

-

GDC details

-

Complaints policy

-

Clear statement if the practice provides NHS treatment, private treatment or a mixture of both

-

Last updated

-

Orthodontists' qualification

-

Orthodontists' country of qualification

-

Orthodontists' GDC number.

For practices providing NHS treatment, a note was made if there was an explicit, accurate statement regarding eligibility for NHS orthodontic treatment. A gold standard of 89% (8/9) was set for the GDC guideline assessment.

LIDA criteria

The websites were graded on three aspects of the LIDA instrument, namely:

-

Accessibility: This section regards the ability of a person to view a website well. How well does the website conform to best practice regarding coding? Is registration required to view the data? Is the website viewable on multiple browsers? This section is important because ensuring that websites are accessible to all is a legal requirement in the UK. This section was graded with a mixture of an automated system provided by LIDA regarding page setup and coding, and a questionnaire

-

Usability: This section regards the ability of a person to use the website effectively and identify the information that they require easily. Is the information presented to the person easy to understand? How simple is the website to navigate? Does the website require a financial commitment to access all available information? This section is important because an easily usable website is more likely to be used by a person. This section was graded solely by use of a questionnaire. Information considered to be likely required by users of the website included: treatment options, price of treatment (assuming private treatment is offered), risks of treatment, opening times, orthodontist details and practice address.

-

Reliability: This section reviews the reliability of information presented on a website. Does the website keep up to date with the newest research on orthodontics? Is the information presented unbiased? Is it in any way dangerous or harmful to the patient? Are claims made about treatment based on sound scientific knowledge, and how is this presented to the user of the website? Is there evidence of review by other experts in the field?

Due to the lack of a peer review system in the publication of many healthcare websites in general,1,3 reliability is perhaps the most important of all the sections measured by the LIDA instrument. This was measured solely by use of a questionnaire. Websites that were deemed to have presented only 'background' information on orthodontics – such as presenting various types of appliance (that is, fixed, removable and functional) and the roles and function of orthodontics were not deemed to require the use of references.

The LIDA questionnaire was used for each website. Each question was rated between zero (never) and three (always) with a higher score in each section associated with a more favourable outcome. A gold standard of 90% for the LIDA was established for each section, as previously used by Cobourne et al.1

Results

All data collected was compiled into a table. Data was collected by a single practitioner in order to reduce variability with regards to the use of the LIDA score. Figure 1 shows a box and whisker representation of the results.

Of a maximum total of nine for assessment of the GDC criteria, practice websites ranged from two (22%) to eight (89%) with a mean average of 5.6 (63%). Requirements of the GDC guideline that were most commonly omitted included a copy of the practice complaints policy (included in 2 out of 30 websites – 6.7%) and an indication of when the website was last updated (8/30 – 27%). GDC details of clinicians and a link to the GDC website were both omitted in 50% of the websites reviewed. The country of qualification of the orthodontist was mentioned in 21/30 sites (70%). Listing of clinicians' qualifications was given in 26 out of 30 websites (87%). Contact details of the practice were listed in 28/30 websites (93%), and all 30 practices listed their address. One website attained the benchmark 89% score. The number of websites compliant with each criteria is shown in Figure 2.

Of 30 websites listed, 24 offered NHS treatment. Of those, 17/24 explicitly stated the correct criteria for acceptance for orthodontic treatment, with one website incorrectly claiming NHS treatment was available for all children.

The LIDA score was split into three key areas – accessibility (A), usability (U) and reliability (R). The websites were scored according to a specific set of questions in each region and a total score found for each website. Total LIDA scores (T) ranged from 79-118/144 (55-82%). The mean average total score was 102.3/144(72%) No website reached attained the 90% benchmark score as set out at the beginning of the study.

Of the three key sections, websites on average scored best in accessibility and worst on reliability. Results were as follows:

-

Accessibility mean average 50.9/63 (81%). Range: 38-60/63

-

Usability mean average 39.5/54 (73%). Range: 26-45/54

-

Reliability mean average 11.7/27 (43%). Range: 6-18/27.

Of 30 websites reviewed, 11 websites (37%) made claims regarding use of self-ligating brackets, including:

-

Provide reduced treatment time as compared to conventional brackets (10)

-

Are more comfortable (4)

-

Reduce the need for orthodontic extractions (4)

-

Reduce root resorption (2).

Few websites listed risks of treatment on their website (6), and 18 sites did not provide price lists of private treatment options. These may be areas that are important for patients to make a choice regarding treatment for their malocclusions.

Discussion

There are two distinct types of search engine available for use. The first is a directory (eg yahoo.co.uk). Here, human editors vet websites that they think may be valuable for users and manually compile a database of websites. Secondly, there are 'spiders' (also known as 'crawlers', such as google.co.uk). These sites automatically compile their lists based on website text or keywords. The use of further search engines within this study (such as Bing UK) would likely have given similar results, as both types of engine were included in the study. As mobile search engines are able to use location data to customise search results, only desktop searches were used.

Following direct contact with clinicians, the internet is the second commonest source of healthcare information for adults.7 In the United States alone 17 million adults have used the internet to research dental information specifically.16

The most common reason why patients research healthcare information online is to search for information relating to conditions and treatment.4 Many clinicians are sceptical of the validity of information found online,5,8 as the Internet is a medium that allows almost anyone to publish information,. This may lead to patients researching information that is inappropriate or inaccurate.3,4,5,6,7

In general, websites poorly adhered to the GDC guidelines. Of 30 websites studied, none scored the maximum of nine out of nine. Four websites achieved the established gold standard of 89% (8/9). In this study, the area that most websites were non-compliant with was the publication of a complaints policy. Publication of such a document may help patients in resolving a complaint more efficiently, and easy access to this document for members of the public may even help prevent such complaints being escalated.

Details of practice services, personnel and qualifications may be seen by members of the public as important before making their decision to seek treatment with a particular clinician or practice. Furthermore, misleading information may damage the relationship between the practitioner and patient irreparably.13 Practices that fail to ensure that relevant details are included, or accurately updated, online as part of their marketing strategy are vulnerable to such complaints in the future.

Nichols et al.15 reviewed dental practice websites and compared them to the Health on the net foundation code of conduct21 with respect to claims made on their websites, and whether such claims had been appropriately referenced. Interestingly, they found that 4% of dental practices made such claims. By contrast, 37% of orthodontic practice websites have made claims regarding treatment, many of which may be outdated or against the available evidence.22,23

When making claims for the efficiency or advantages of any form of treatment, practitioners must be careful to ensure that such statements are based on the best available evidence rather than claims made by manufacturers. This is of particular importance as a high number of claims that reached the Fitness to Practise panel in 2009 were related to claims by practitioners made on forms of treatment.12 Publishing accurate information online may reduce the possibility of a disagreement over a course of treatment.5,10 Practitioners should also consider publishing references alongside such claims to provide reassurance that they are following the evidence base.

Orthodontic practices may also like to consider discussing the limited eligibility of children to be treated under the NHS and ensure any statements regarding this are kept contemporaneous to ensure that patients are not misled.

Practices performed relatively poorly with the LIDA scores. Three websites scored above the 90% standard for accessibility. This was the best scoring of the three sections, with reliability scoring the worst. Although the overall score of 71% falls below standards set, it is higher than average scores reported by Cobourne1 and Livas.16

The use and reporting of a sound evidence base for information posted online could increase reliability scores by up to 30%. Furthermore, external review of the website, both by independent experts and patients would evidence a more reliable source of information. Frequent updates and response to recent events (such as through a blog) would improve scores further. Practitioners looking to improve usability scores also have a number of options. A clear statement of which demographic would be treated in the practice should be included in the site. A well-structured site with consistent page layout is a simple way to make a more usable website. The highest scoring websites included videos and pictures, which would be used to highlight treatment options or to promote other areas of the practice itself.

The LIDA instrument has been demonstrated to have good internal validity.19 A criticism of the tool is certainly that there seems to be little evidence of external validity, of how well the tool correlates with other tools used to assess healthcare websites. However, it must be borne in mind that there currently appears to be no single 'gold standard' for assessing healthcare websites, and as such measuring its external validity may be problematic. The LIDA tool has demonstrated, however, that it can be used over a wide spectrum of specialties.1,17,18,19 It was also chosen for this study as it enabled an in-depth review of each website. Other instruments were discarded due to their lack of breadth in this regard.

Conclusion

In summary, practices complied poorly with the GDC ethical advertising criteria. This document was produced as a response to a high number of complaints reaching the Fitness to Practise Committee surrounding advertising. As such, it is important for websites to include accurate, contemporaneous information, and for them not to mislead the public. Any claims from practices regarding the efficacy of their treatment must be founded on a sound evidence base, and clinicians should consider reporting the source of such statements. It is hoped that this paper will draw attention to and raise awareness of the GDC guidelines on ethical advertising and help to improve the quality of information made available to the public.

References

Patel U, Cobourne M T . Orthodontic extractions and the internet: quality of online information available to the public. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011; 139: e103–e109.

Riordain R, McCreary C . Dental patients use of the Internet. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 583–586.

Guardiola-Wanden-Berghe R, Sanz-Valero J, Wanden-Berghe C. Quality assessment of the website for eating disorders: a systematic review of an impending challenge. Cien Saude Colet 2012; 17: 2489–2497.

Aldairy T, Laverick S, McIntyre G T . Orthognathic surgery, is patient information on the internet valid? Eur J Orthod 2012; 34: 466–469.

Koch-Weser S, Bradshaw Y S, Gualtieri L, Gallagher S S . The Internet as a health information source: findings from the 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey and implications for health communication. J Health Commun 2010; 15: 279–293.

Longille M, van Zanten S V, Shanavaz S, Massoud E . Systematic evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea websites on the internet. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012; 41: 265–272.

Ayuntunde A A, Welch T, Parsons L . A survey of patient satisfaction and use of the internet for health information. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61: 458–462.

Chestnutt I G, Reynolds K . Perceptions of how the Internet has impacted on dentistry. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 161–165.

Powell J A, Darvell M, Grey J A . The doctor, the patient and the world wide web: how the internet is changing healthcare. J R Soc Med 2003; 96: 74–76.

Anderson J G, Rainey M R, Eysenbach G . The impact of CyberHealthcare on the physician-patient relationship. J Med Syst 2003; 27: 67–84.

General Dental Council. Principles of ethical advertising. London: GDC, 2012. Online article available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/Dentalprofessionals/Standards/Pages/Ethical-advertising.aspx (accessed February 2014).

General Dental Council. Ethical advertising consultation May 2010. London: GDC, 2010. Online information available at http://www.gdc-uk.org/aboutus/thecouncil/meetings%202010/item6papere_ethical%20advertising%20consultation.pdf (accessed February 2014).

General Dental Council. Ethical advertising consultation December 2011. London: GDC, 2011. Online information available at http://www.gdc-uk.org/aboutus/thecouncil/meetings%202011/item%206%20ethical%20advertising%20guidance.pdf (accessed February 2014).

Kravitz A S, Treasure E T . European Council of Dentists manual of dental practice. European Council of Dentists, 2009. Online manual available at http://www.eudental.eu/index.php?ID=35918 (accessed February 2014).

Nichols L C, Hassall D . Quality and quantity of dental practice websites. Br Dent J 2011; 210: E11.

Livas C, Delli K, Ren Y . Quality evaluation of the available internet information regarding pain during orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 2013; 83: 500–506.

Grewal P, Alagaratnam S . The quality and readability of colorectal cancer information on the internet. Int J Surg 2013; 11: 410–413.

Grewal P . Quality of vascular surgery Web sites on the Internet. J Vasc Surg 2012; 56: 1461–1467.

Minervation. The LIDA Instrument 2007. Online information available at http://www.minervation.com/does-lida-work/#more-964 (accessed February 2014).

The Kolberg Partnership. What are the top UK search engines? Online information available at http://www.kolberg.co.uk/answers.php?s=uks&q=0 (accessed February 2014).

Health on the Net Foundation. The HON code of conduct for medical and health websites (HONcode). Online code available at http://www.hon.ch/HONcode/Conduct.html (accessed February 2014).

Chen S S, Greenlee G M, Kim J E, Smith, C L, Huang G J . Systematic review of self-ligating brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010; 137: e1–e18.

Čelar A, Schedlberger M, Dörfler P, Bertl M . Systematic review on self-ligating vs. conventional brackets: initial pain, number of visits, treatment time. J Orofac Orthop 2013; 74: 40–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parekh, J., Gill, D. The quality of orthodontic practice websites. Br Dent J 216, E21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.403

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.403

This article is cited by

-

The quality and content of websites in the UK advertising aligner therapy: are standards being met?

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Advertising and facial aesthetics in primary care: how compliant are practice websites and social media with published guidance?

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Evaluation of the quality of information on the internet about 2019 coronavirus outbreak in relation to orthodontics

Health and Technology (2021)

-

The informative value and design of orthodontic practice websites in The Netherlands

Progress in Orthodontics (2020)

-

The quality of information available on the internet for patients wishing to make a complaint against an orthodontic practitioner

BDJ In Practice (2020)