Abstract

This work reports a facile method for preparing the new photoactive In2O3 films as well as their implementation in photoelectrochemical (PEC) application. We firstly investigated the relationship between oxygen vacancies (VO) and PEC performance and revealed a rule between them. We found that the optimized In2O3−n sample yielded a photocurrent density up to 3.83 mA/cm2 in 1 M Na2SO4 solution under the solar illumination. It also gave efficiency as high as 75% over 400 nm in the incident-photon-to-current-conversion efficiency (IPCE) spectrum, which is the best value for an In2O3 photoanode reported. Moreover, the PEC performance of these films is enhanced as the VO increased and then decreased with further increasing VO. This two-side effect means VO can favor the photoelectron activation, or act as recombination centers to prohibit the generation of photocurrent. Making highly photoactive In2O3 nanostructures in this work will open up new opportunities in various areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advanced materials for utilizing renewable energy from sources such as biofuels, wind, photoelectric, geothermal and hydrogen have widely attracted interest and investigation for addressing energy crisis. In these decades, considerable efforts have been made in these areas. And it is well known that the underexploited potential of solar energy remains a limitless source, especially its conversion to hydrogen energy via photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting. Since it was introduced in 1991, the low-cost, high-efficiency, PEC solar cell has attracted intensive interest as a promising candidate for future green energy1. However, the overall power conversion efficiency is still too low and this needs to be further improved before the technology can be commercialized. The overall sunlight-to-electric-power conversion process in a PEC cell can be summarized as the successive procedure of photogeneration, charge-carriers transport and collection. There are two major approaches to enhance sunlight harvesting improving photoelectrochemical efficiency and stability of an electrode. The first approach is to develop nanostructured electrodes with extremely large effective area to improve the charge-carrier transport capability of active layer. Employment of functional nanostructured photoanodes such as nanotubes, nanowires and nanofibers, nanotrees and nanoforests2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 have been used in PEC and these nanostructures exhibit higher specific capacitances than their bulk counterparts. The second approach is to introduce the photonic crystal10,11, doped with lower bang gap semiconductor12 or include a light-scattering layer13,14,15 to trap more light in the device. Nevertheless, some methods are limited by high cost and complex procedure and most of them are not easily controllable. It is highly desirable to fundamentally improve the sunlight harvesting and charge-carrier transport behavior of metal oxide electrodes.

Indium oxide (In2O3) is of great interest for various technological applications ranging from optoelectronics to chemical sensors because of its unique properties of high transparency and simultaneously metallic conductivity16,17. In2O3 satisfy some important demands for the direct photoelectrolysis of water splitting. With excellent conductivity and stability, its position of the conduction and valence band edges right bracket the redox potentials of water18. In these decades, not much research focus on the application of In2O3 as a photovoltaic material The large band gap of In2O3 (3.5 eV) makes it inefficient in utilizing visible light, so the overall power conversion efficiency is too low while applied in a PEC cell. For instance, the previous reported photogenerated current densities of In2O3 films (0.75 mA/cm2)19 are significantly smaller than that obtained from other metal oxides such as TiO2, CdS, CdSe. The relatively weak results were attributed to the poor photoelectro-activity and poor charge-carrier transport in In2O3. Therefore, addressing the shortcomings in In2O3 during the photovoltaic process remains an important subject for developing the In2O3 photo-electro devices.

It still remains unclear that how the oxygen vacancies (VO) or other defect states affect the performance of the In2O3 semiconductor in photoelectric transfer. We hypothesize that introducing VO into In2O3 microstructure could break through these limitations and thus improve PEC performance of In2O3 materials. This is motivated by our recent demonstration that specific capacitance of TiO2 nanostructures are significantly improved by increased donor densities resulted from introduction of oxygen vacancy states via thermal treatment in hydrogen atmosphere20. For the design of high-performance photovoltaic materials in the field of solar energy conversion, in our research work, we have developed a facile controllable method to synthesized In2O3−n nanocubes that possess different amount of oxygen vacancies without using hydrogenation. Accordingly, this method we used is simple, low-cost, easy to scale and very environmental friendly. Then, we are the first who extensively investigate the effects of VO on the PEC performance of In2O3 nanostructure. This work aims at providing a new insight the effects of VO in upgrading phototelectrochemical properties in microscopic scale.

Results

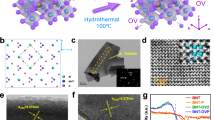

The surface morphology of the as-prepared In2O3 samples were investigated by SEM and the result of the In2O3 nanocubes prepared via cathodic electrodeposition followed by 350°C annealing is presented in Figure 1a. Smooth surfaces of the nancubes can be observed and the angle between the adjacent edges is measured relatively close to 90°. The cube is simply enclosed with 3 crystal faces of surfaces21. Figure 1c shows a low-magnification TEM image of a single In2O3 nanocube with the diameter of about 300 nm. Figure 1b is the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of the selected area marked in Figure 1c, disclosing the lattice fringe spacing of 0.30 nm (see the magnified HRTEM in Figure 1d), which matches well with the (222) lattice spacing of body-centered-cubic (bcc) In2O3. Figure 1g is the corresponding SAED pattern of a cube (marked by a dashed circle in Figure 1c), confirming that the pseudo-polycrystalline structure of a nanocube was formed after annealing. The spot rings can be indexed as the (222), (125) and (662) planes, corresponding to the bcc structure In2O3. Figure 1e,f displays the enlarged image of the HRTEM (marked by the dashed square in Figure 1b), which exhibits clear fault zone and misfit dislocations. This confirms the existence of defects in the In2O3 nanocubes, which is concerned with the PEC performance of them below.

(a) SEM images of the as-synthesized In2O3 nanocubes on FTO substrates. (b,c) HRTEM image and HRTEM image of a single In2O3 nanocube. (d) Enlarged image of the white square marked in (b). (e,f) Enlarged image of the selected part (yellow, blue Square) marked in (b), (g) SAED pattern of the area marked in the TEM image of (c).

To further determine the crystal structure and possible phase transformation during different annealing temperature, XRD patterns of the as deposited In(OH)3 untreated, air-annealed at 250°C, 350°C, 450°C were collected in Figure 2. The patterns clearly show that the untreated electrodeposited sample is In(OH)3 (JCPDF # 16-0161) and it transform to In2O3 (JCPDF # 06-0416) above the temperature 250°C in air atmosphere. Apart from this, the peak intensity of In2O3 gradually become stronger as the annealing temperature increased, suggesting the crystal structure of In2O3 may be modified in oxygen atmosphere at 450°C. It can be deduced that, annealing of In2O3 in an oxygen sufficient environment at higher temperature will promote the phase transformation and enhanced crystallinity22.

The defect states of as-prepared sample treated in different temperature and environment were analyzed using room temperature Raman-scattering, as shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information). Figure 3 displays the Raman shift data from 50–800 cm−1. Two very low frequency sets at 103 and 130 cm−1, two low frequency sets at 302 and 366 cm−1 and two high frequency sets at 494 and 629 cm−1 belong to the vibration modes of bcc-In2O3, which agree well with the reported values in the literature23,24. In fact body-centered cubic In2O3 belongs to the space group Ia3, Th25. The structure contains two kinds of cations: 8 In3+ with side symmetry S6 and 24 In3+ with point symmetry C2. The 48 oxygen atoms in the body-centered cell are on general positions (e) with C1 site symmetry. For such a structure, the following vibration modes are predicted26:

The vibrations with symmetry Ag, Eg and Tg are Raman active and infrared inactive, while the Tu vibrations are infrared active and Raman inactive. The Au and Eu vibrations are inactive in both infrared and Raman measurements. The peak at 131 cm−1 is assigned to the In-O vibration of InO6 structure units27. The scattering feature at 308 cm−1 is usually interpreted as the bending vibration δ (InO6) of octahedrons28. The other two peaks 497 and 630 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the same ν (InO6) octahedrons, whereas the 367 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibrations of the In-O-In. It's worth noting that it also reflects the oxygen vacancies in the In2O3 structure29. Moreover, under the same heating temperature, the relative intensity of the above In-O-In defects shown in Figure 3 of the 250°C sample is higher than those in 350°C and 450°C, implying In2O3 nanocubes heated inhigher temperature possess less oxygen vacancies30.

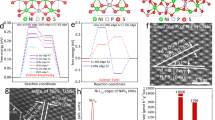

In order to understand the chemical composition and defect state of the product, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was performed on the different In2O3 samples. Figure 4a displays the In 3d core level spectrum of the three In2O3 nanocubes. A perfect fit to two peaks located at 444.6 and 452.1 eV are clearly observed, which can be attributed to the characteristic spin-orbit split 3d5/2 and 3d3/2, respectively31. This result indicates the Indium valency is mainly +3 in the product. As the annealing temperature increased, the chemical state of In did not change much. It can be deduced that the annealing process won't affect the In3+ in the lattice structure. Figure 4b is the O 1s core level spectrum, clearly showing that two peaks can be identified. The peak at about 529.9 eV originates from the oxygen bond of In–O–In and the peak at 531.6 eV corresponds to the oxygen defects in the matrix of metal oxide31,32. As for the sample treated in air atmosphere, their peak area of 531.6 eV is clearly different, with the ratio of 250Air:350Air:450Air = 3.5:3.1:2.4. This indicates that the oxygen vacancies of the samples vary from 250°C to 450°C. That is to say, lower heat treatment temperature will promote the oxygen vacancies' existence.

(a) Normalized In 3d core level XPS spectra of 250°C (black diamond), 350°C (blue circle), 450°C (red triangle) - air In2O3 film; (b) Curve fitting of the O 1 s peak in the XPS spectrum of 250°C, 350°C, 450°C - air In2O3 film, respectively. Black circles are the experimental data, which are deconvoluted into two peaks centered at 529.9 eV (green dashed curve) and 531.6 eV (pink dashed curve).

For better understanding the presence of defects in the samples, we used a combined fluorescence lifetime and steady state spectrometer (EDINBURGH) to investigate the room temperature photoluminescence (PL) spectra of samples, as shown in Figure 5. Our In2O3 nanocubes have a strong and sharp PL emission centered at 405 nm. It is known that emission spectra can be divided into two broad categories: the near-band-edge (NBE) emissions and deep-level (DL) emissions. The NBE emissions can be favored by the high crystal quality and quantum confinement effect and the DL emissions can be enhanced by impurities, or structure defects of the crystal33,34. The detectable 405 nm emission at room temperature is mainly attributed to the existence of surface oxygen vacancies and defects of In2O3 nanocubes, which may lead to a high DL-emissions-to-NBE-emissions ratio35,36,37. The PL spectra of our In2O3 nanocubes exhibit a blue-shifted emission peak positioned at 405 nm in comparison with the result reported by other groups38,39. This may be due to the singly ionized oxygen vacancies in In2O3 and the emission results from the radioactive recombination of a photogenerated hole with an electron occupying the oxygen vacancy36,37.

As compared to In2O3 nanocubes obtained in 450°C, the intensity of emission peaks gradually strengthened for those in 350°C and 250°C. One is note that their positions in the emission spectra are identical to each other. We consider the intensity of emission peaks of In2O3 obtained at 250°C increased as a result of more oxygen vacancies and defects. With increasing calcination temperature and air-sufficient atmosphere, the crystallinity of the samples was improved, which caused a rapid reduction of oxygen vacancies and defects.

PEC studies on three In2O3 nanocube films, 250°C-air, 350°C-air and 450°C-air, have been carried out to understand the effect of oxygen vacancies on In2O3 nanocube-based photoanode for PEC hydrogen generation. Linear sweep voltammograms and incident photon to current conversion efficiency (IPCE) measurements were conducted on a CHI 660D electrochemical workstation with a 150 W xenon arc lamp as the white light source. The electrolyte used was a 1 M Na2SO4 aqueous solution. IPCE measurements were carried out in the same electrolyte at zero bias (0 V vs Ag/AgCl). The linear sweep voltammograms in a potential range of −0.6 to 0.5 V recorded from these samples in the dark and with white light illumination of 100 mW/cm2 are shown in Figure 6. By analyzing these data, we reached two important conclusions. First, all samples show a drastic increase in photocurrent density at an onset potential of −0.35 V vs Ag/AgCl and the photocurrent saturated at a substantially lower potential of 0 V vs Ag/AgCl (1.0 V vs RHE). The negative shift of saturation potential indicates that the charge separation and transportation in the samples are more efficient. Second, when the light was on, the photocurrent densities of these films are enhanced as the annealing temperature increased from 250 to 350°C and then decreased with further increasing temperature. It confirms that changing annealing temperature is a simple and effective method for controlling the PEC performance of In2O3. The highest photocurrent was recorded in 350°C-air sample up to 3.83 mA/cm2. Under visible light illumination (using UV filter, λ>400 nm), all the annealing samples still exhibit strong photocurrent response feature and the order of intensity of the samples remain the same as before. (Figure 6b) The best photocurrent reaches 2.60 mA/cm2, which is the best value for an In2O3 photoanode reported. This present result is much higher than the reported values of In2O3 nanospheres (0.75 mA/cm2 at 0.0 V)19, N-doped In2O3 (0.30 mA/cm2 at 0.2 V)40 and TiO2@In2O3 (0.12 mA/cm2 at 0.2 V)41.

In order to make a quantitative correlation between all the samples treated in different conditions, we performed incident-photon-to-current-conversion efficiency (IPCE) measurements as a means of studying the photoactive wavelength regime for the nanostructured In2O3 films (Figure 7). IPCE can be expressed as42

Where I is the photocurrent density, λ the incident light wavelength and Jlight is the measured irradiance. As shown in Figure 7, the IPCEs measured for the four film types were consistent with the I-V curves, with the 350°C air films giving the highest efficiency. Around 400 nm, it gave IPCE values up to 75%. The onset wavelengths of photocurrents were 575, 550 and 525 nm for 350°C air, 250°C air and 450°C air films, respectively, which are well match the results of the UV-vis absorption spectra. (Figure S2, Supporting Information) The 450°C film had a strong photoresponse in the UV region but little photoresponse in >400 nm. In contrast, the 350°C air showed substantial photoactivity in the visible light region from 350 to 550 nm in addition to strong photoresponse in the near-UV. These results clearly confirm that the existence of oxygen vacancies improves the visible light absorption, while excess of them has a reversible effect on IPCE. It significantly decreases the IPCE throughout the entire visible to near-UV region for the 250°C sample which possesses the most defects.

Discussion

Such enhanced photoelectrochemical performance of annealed In2O3−n nanocubes can be attributed to the improved electrical conductivity43, crystallinity and increased oxygen vacancies group after annealing, which can provide more efficient transport pathways for electrons and contribute more charge carriers. As well known, the photocurrent densities are closely related to the generation of photoelectrons. And the transfer of them has to be taken into consideration. The defect states are well acknowledged to dominate the transfer of photoelectrons. The amount of defect states in semiconductors can be estimated from the discussion of Raman spectra, XPS, PL above. As shown in Figure 3–5. The result correspondingly implies that the amount of defect state in In2O3 nanocubes is 250°C air (larger n)> 350°C air > 450°C air (smaller n). The PEC performance recorded from the sample indicates that oxygen vacancies and defect states have a two-faced effect on the charge carrier transfer process promoting photocurrent. Figure 8 shows the plot of the best IPCE efficiency at the visible wavelength over 400 nm of different In2O3−n films as a function of the relative oxygen vacancy amount, which clearly reveals the relationship between VO and PEC properties.

Firstly, oxygen vacancies were formed while calcinating the sample and the process can be interpreted as below:

The hydroxyl group in the indium hydroxide lattice will be removed in the form of water vapour during calcination. Some of the lattice oxygen may also be released in the form of O2 gas, thus leaving oxygen vacancies. The relation depicted below describes the formation of oxygen vacancy:

The neutral oxygen vacancies may be singly ionized ( ) or doubly ionized (

) or doubly ionized ( ):

):

Where Vo is the neutral oxygen vacancy and Oox is an oxide anion in a regular lattice site, e− is an electron in the conduction band.

The electronic state of In2O3 was calculated by the molecular orbital (MO) theory and CASTEP method, as shown in the Supporting Information, Figure S3. The effects of oxygen vacancies on the energy levels were studied as well. In2O3 has the cubic bixbyite structure in which O2− ions occupy orderly in three-fourths of the tetrahedral interstices of a face-centered-cubic In3+ ion array41. In2O3 should have a filled O2−: 2p valence band that is primarily oxygen 2p in character. The In: 3d10 core lies well below the valence-band edge Ev. The conduction band Ec mainly consists of In: 5s and In: 5p, as shown in Figure 9a. The O2−: 2p states are bonding, the In: 5s states are antibonding. The as prepared indium oxide with oxygen vacancies was indicated as In2O3−n where n (amount of Vo) symbolizes a vacant tetrahedral interstice of the face-centered-cubic In3+ ion array. Of these vacancies, part of the In3+ ion are ordered and n/2 per In3+ ion are randomly distributed over the O2− ion subarray. Thus the Vo signifies oxygen-array vacancies. Each Vo is surrounded by In3+ ion 5s orbitals that are stabilized from the In 5s band by a lack of covalent bonding with the missing O2− ion; therefore, symmetrized In 5s orbitals at each Vo form shallow donor state level just below Ec that accommodate two electrons per oxygen vacancy. That is to say, the shallow donor state originated from In 5s orbitals, which can be called a new vacancy level, is created by loss of oxygen atoms. Our calculation result shows that the first and second vacancy level is about 0.055 eV and 0.094 eV below Ec for low n, (Figure S3, Supporting Information) which is in accord with the measurements of Weiher et al44.

(a) Energy diagram of In2O3−n with different n value. 250°C sample represents the larger n and 450°C sample represents the smaller n. E1OV and E2OV are referred to the induced oxygen vacancies located below the In2O3 conduction band. Arrows highlight the possible electronic transitions between the different energy levels in In2O3−n; (b) Schematic illustration of excess oxygen vacancies' roles on the transfer of photoelectron in PEC processes.

On the other hand, according to the MO theory, O atoms in the nearest neighbor position form a bonding orbital and an antibonding orbital with In atom. If the bonds break, the energy of the bonding orbital increases and the energy of the antibonding orbital decreases. At high Vo concentrations (i. e., larger n), a Vo impurity band, which consists of unlocalized molecular orbital, forms by newly generated bonding energy. It overlaps Ec at the bottom of the conduction band, thus producing a degenerate semiconductor. The Vo impurity band acts more like a electron trapper demoting them transfer between Ev and Ec. Furthermore, the molecular orbital in the valence band, which has a large contribution from oxygen atoms near the vacancy, shifts by 0.08 eV45 due to the lack of oxygen. This situation is shown schematically in Figure 9a.

Base on the discussion above, the vacancies related to the preparing process can act as donors and induce the formation of new energy levels in the band gap. We believe oxygen vacancies in the In2O3 structure play a critical role in the visible light absorption. XPS data confirmed that the all samples are not doped with other elements, so the possible defect states are attributed to the formation of oxygen vacancies. Based on the In2O3 band gap (Figure S4, Supporting Information) and the energy levels of oxygen vacancies, we construct a simplified energy diagram illustrating the transport of electrons in different In2O3 films (referenced to normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) to compare the efficiency between them more clearly. The strong UV absorption of In2O3 is due to the electronic transition from the valence band to the conduction band. (Figure S2, Supporting Information) The visible light absorption can be attributed to the electron transition from the In2O3 valence band to the new oxygen vacancy energy levels, or from the oxygen vacancies to the conduction band46,47,48. Therefore, it is possible to use less energy per time to activate the photoelectrons and thus effectively improve the carrier separation efficiency. Here, the oxygen vacancy is a key role in promoting photoelectrochemical performance. (Figure 9a, middle)

Secondly, the sample annealed in 250°C air proved to possess a greater number of defect states and oxygen vacancies, but it does not exhibit the best photocurrent density. Consequently, it can be deduced that it is not the case that the more defect states the materials have, the greater the PEC performance. We suppose that excess defects act more as the electron pool to demote the PEC property. In photoelectric measurement, the film electrode is used and the production of photocurrent relies on the amount of photoelectrons transferred from semiconductor to the FTO glass substrate. Increasing amount of oxygen vacancies will result in more photogenerated electrons trapped and immobilized in the defect states, thereby diminishing the chance to contribute to the photocurrent generation. Furthermore, when too many oxygen atoms are missing in the In2O3−n (n is large), an unlocalized molecular orbital exists below the bottom of the conduction band43. Meanwhile, Vo impurity band also forms and overlaps Ec at the bottom of the conduction band, which leads to low efficiency in excitation of the mobile electrons to conduction band. It may conclude that the photoelectron trapped in the defect state and unlocalized molecular orbital are ineffective to the photocurrent generation. So the excess oxygen vacancies in In2O3 play a recombination centres role of photoelectrons and holes rather to prohibit the generation of photocurrent than to promote it. The scheme of the mechanism during this process is illustrated in Figure 9b.

In summary, our work has demonstrated that annealing treatment in different atmosphere can be used as a simple general strategy to fundamentally control the performance of In2O3 materials as photoanodes for PEC application. The amount of defect states in In2O3 is controlled by the annealing temperature and gas atmosphere and they can be characterized from the analysis of Raman spectra, XPS and PL. The result clearly shows that the amount of defect state in In2O3 nanocubes is 250°C air > 350°C air > 450°C air. The best In2O3 material (350°C air) yield substantially enhanced photocurrent densities and the photocurrents saturated up to 3.83 mA/cm2 at a low applied bias of 0.0 V vs Ag/AgCl (1.0 vs RHE). Around 400 nm, it gave IPCE values up to 75%, which is the best value for an In2O3 photoanode reported. The PEC comparison of those samples reveals that oxygen vacancies have a two-side effect on the performance. Because they may induce the new energy levels to facilitate the electron transition from valence band to conduction band with less activating energy. And they also act as donors enhancing the photocurrent. However, excess oxygen vacancies may trap the photogenerated electrons and act as recombination centers to diminish the photocurrent as well. The optimized amount was found in 350°C air film. More importantly, since In2O3 is a new class of semiconductors, the capability of making highly photoactive In2O3 nanostructures opens up new opportunities in various areas, including PEC water splitting, dye-sensitized solar cells and photocatalysis. By replacing the O atom in our In2O3 lattice with other atoms such as H, N, S, the efficiencies and these novel devices' properties are expected to be greatly improved. Further work is stilling undergoing in our laboratory.

Methods

Preparation of in(OH)3 nanostructures

All chemicals were purchased as guaranteed regents and used without further purification. The analytical grade In(NO3)3·3H2O was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China. In(OH)3 were synthesis via a template-free electrochemical growth method that performed in a conventional three-electrode glass cell using a homemade HDV-7C potentiostatic apparatus as power source. F-doped SnO2 coated glass (FTO) with a sheet resistance of 14 Ω/sq was used as working electrodes. A graphite rod of about 4.0 cm2 and a saturated Ag/AgCl that connected to the cell with a double salt bridge were used as counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. Before electrodeposition, the FTO glass was cleaned ultrasonically in distilled water, ethanol and acetone and then rinsed in distilled water. In(OH)3 nanocubes were grown in an electrolytic solution contained 0.008 M In(NO3)3 at a constant potential of −1.2 V at 70°C. After deposition, the film was washed by water and dried in air at 25°C for 10 h.

To control synthesis the In2O3 nanostructures with VO, we used a thermal decomposition method at different atmosphere. The as deposited In(OH)3 samples were annealed in air at 250°C, 350°C, 450°C, respectively. All the annealing time was kept at 3 h.

Material characterizations

The surface morphology and composition of prepared products were analyzed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM-6330F). The structures of the samples were investigated via X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker, D8 ADVANCE) with Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, 200 kV, JEM2010-HR). The chemical state and compositions of products were analyzed using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALab250). The optical properties of the samples were measured with a UV-vis-NIR spectrophotometer (UV, Shimadzu UV-2450) and a combined fluorescence lifetime and steady state spectrometer (PL, EDINBURGH). The In2O3 measurements of SEM, XPS, XRD, PL and UV-spectra were directly carried out on the samples without removing the substrates.

Photoelectrochemical characterizations

PEC measurements were carried out in a three-electrode cell with a flat quartz window to facilitate illumination of the photoelectrode surface. The cell consisted of Pt wire as the counter electrode, Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode and the products prepared on FTO substrates as the working electrode, respectively. A 1 M Na2SO4 aqueous solution was used as the electrolyte. Linear sweeps were measured by a CHI 660D electrochemical station, under simulated sunlight with a 150 W xenon lamp (Newport 6255) coupled with an AM 1.5 global filter (Newport 81094). All the measurements, except gas collection experiment, were done with the front side illumination. Incident-photon-to-current-conversion-efficiencies (IPCE) were collected by a Solartron 1280B electrochemical station with a solar simulator (Newport 69920, 1000 W xenon lamp), coupled with an infrared water filter (Oriel 6127) and aligned monochrometor (Oriel Cornerstone 130 1/8 m).

References

O'Regan, B. & Gratzel, M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 353, 737–740(1991).

Varghese, O. K., Paulose, M. & Grimes., C. A. . Long vertically aligned titania nanotubes on transparent conducting oxide for highly efficient solar cells. Nat. Nanotechnol 4, 592–597(2009).

Law, M., Greene, L. E., Johnson, J. C., Saykally, R. & Yang, P. Nanowire dye-sensitized solar cells. Nat. Mater 4, 455–459(2005).

Ko, S. H. et al. Nanoforest of hydrothermally grown hierarchical ZnO nanowires for a high efficiency dye-sensitized solar cell. Nano Lett. 11, 666–671(2011).

Lu, X. H. et al. Facile synthesis of free-standing CeO2 nanorods for photoelectrochemical applications. Chem. Commun. 46, 7721–7723(2010).

Solarska, R., Krolikowska, A. & Augustynski, J. Silver Nanoparticle induced photocurrent wnhancement at WO3 photoanodes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 7980–7983(2010).

Su, J., Feng, X. J., Sloppy, J. D., Guo, L. & Grimes, C. A. Vertically aligned WO3 nanowire arrays grown directly on transparent conducting oxide coated glass: synthesis and photoelectrochemical properties. Nano Lett. 11, 203–208(2011).

Tilley, S. D., Cornuz, M., Sivula, K. & Gratzel, M. Light-induced water splitting with hematite: improved nanostructure and iridium oxide catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 49, 6405–6408(2010).

Zhao, W. Y. et al. Electrodeposition of Cu2O films and their photoelectrochemical properties. CrystEngComm. 13, 2871–2877(2011).

Yip, C. H., Chiang, Y. M. & Wong, C. C. Dielectric band edge enhancement of energy conversion efficiency in photonic crystal dye-sensitized solar cell. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 8735–8740(2008).

Halaoui, L. I., Abrams, N. M. & Mallouk, T. E. Increasing the conversion efficiency of dye-sensitized TiO2 photoelectrochemical cells by coupling to photonic crystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 6334–6342(2005).

Yu, X. Y., Liao, J. Y., Qiu, L. Q., Kuang, D. B. & Su, C. Y. Dynamic study of highly efficient CdS/CdSe quantum dot-sensitized solar cells fabricated by electrodeposition. ACS Nano. 5, 9494–9500(2011).

Hore, S., Vetter, C., Kern, R., Smit, H. & Hinsch, A. Influence of scattering layers on efficiency of dye-sensitized solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 90, 1176–1188(2006).

Hore, S. et al. Scattering spherical voids in nanocrystalline TiO2-enhancement of efficiency in dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem Commun. 41, 2011–2013(2005).

Koo, H. J. et al. Nano-embossed hollow spherical TiO2 as bifunctional material for high-efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. Adv. Mater. 20, 195–199(2008).

Nguyen, P. et al. Direct integration of metal oxide nanowire in vertical field-effect transistor. Nano Lett. 4, 651–657(2004).

Wang, Ch.Y. et al. Integration of In2O3 nanoparticle based ozone sensors with GaInN/GaN light emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 103509(2007).

Nozik, A. J. Photoelectrochemistry: applications to solar energy conversion. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 29, 189–222(1978).

Sharma, R., Mane, R. S., Min, S. K. & Han, S. H. Optimization of growth of In2O3 nano-spheres thin films by electrodeposition for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Alloys Compd. 479, 840–843(2009).

Lu, X. H. et al. Hydrogenated TiO2 nanotube arrays for supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 12, 1690–1696(2012).

Yan, T. et al. Urea-based hydrothermal growth, optical and photocatalytic properties of single-crystalline In(OH)3 nanocubes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 325, 425–431(2008).

Salari, M., Konstantinov, K. & Liu, H. K. Enhancement of the capacitance in TiO2 nanotubes through controlled introduction of oxygen vacancies. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 5128–5133(2011).

Rojas-Lopez, M., Nieto-Navarro, J., Rosendo, E., Navarro-Contreras, H. & Vidal, M. A. Raman scattering study of photoluminescent spark-processed porous InP. Thin Solid Films. 379, 1–6(2000).

Korotcenkov, G. et al. Structural stability of indium oxide films deposited by spray pyrolysis during thermal annealing. Thin Solid Films. 479, 38–51(2005).

Imai, H., Tominaga, A., Hirashima, H., Toki, M. & Asakuma, N. Ultraviolet-reduced reduction and crystallization of indium oxide films. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 203–208(1999).

Ferraro, J. R. & Nakamoto, K. Introductory Raman Spectroscopy; Academic Press: Boston, 1994.

Zhu, H., Wang, X. L., Yang, F. & Yang, X. R. Template-Free, surfactantless route to fabricate In(OH)3 monocrystalline nanoarchitectures and their conversion to In2O3 . Cryst. Growth Des. 8, 950–956(2008).

Kaur, M. et al. Room-temperature H2S gas sensing at ppb level by single crystal In2O3 whiskers. Sens. Actuators, B 133, 456–461(2008).

Baszczuk, A. et al. Luminescence properties of europium activated SrIn2O4 . J. Alloys Compd. 394, 88–92(2005).

Lu, X. H. et al. Facile electrochemical synthesis of single crystalline CeO2 octahedrons and their optical properties. Langmuir 26, 7569–7573(2010).

Li, B. X. et al. In2O3 Hollow Microspheres: Synthesis from designed In(OH)3 precursors and applications in gas sensors and photocatalysis. Langmuir 22, 9380–9385(2006).

Mai, L. et al. Lithiated MoO3 nanobelts with greatly improved performance for lithium batteries. Adv. Mater. 19, 3712–3716(2007).

Liang, C., Meng, G., Lei, Y., Phillipp, F. & Zhang, L. Catalytic growth of semiconducting In2O3 nanofibers. Adv. Mater. 13, 1330–1333(2001).

Seo, W., Jo, H., Lee, K. & Park, J. Preparation and optical properties of highly crystalline, colloidal and size-controlled indium oxide nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 15, 795–797(2003).

Kong, Y. C., Yu, D. P., Zhang, B., Fang, W. & Feng, S. Q. Ultraviolet-emitting ZnO nanowires synthesized by a physical vapor deposition approach. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 407–410(2001).

Bagnall, D. M. et al. High temperature excitonic stimulated emission from ZnO epitaxial layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 73, 1038–1041(1998).

Jeong, J. S. & Lee, J. Y. Formation mechanism and photoluminescence of necklace-like In2O3 nanowires. Materials Letters 65, 1693–1695(2011).

Dong, H. X. et al. Indium oxide octahedra optical microcavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 223114(2010).

Li, Y., Bando, Y. & Golberg, D. Single-crystalline In2O3 nanotubes filled with In. Adv. Mater. 15, 581–585(2003).

Reyes-Gil, K. R., Sun, Y. P., Reyes-García, E. & Raftery, D. Characterization of photoactive centers in N-Doped In2O3 visible photocatalysts for water oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 12558–12570(2009).

Poznyak, S. K., Talapin, D. V. & Kulak, A. I. Structural, optical and photoelectrochemical properties of nanocrystalline TiO2-In2O3 composite solids and films prepared by Sol−Gel method. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 4816–4823(2001).

Varghese, O. K. & Grimes, C. A. Appropriate strategies for determining the photoconversion efficiency of water photoelectrolysis cells: A review with examples using titania nanotube array photoanodes. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 92, 374–384(2008).

Wyckoff, R. W. G. Crystal Structures, 2nd ed (Wiley, New York,), 2, 2 (1964).

Weiher, R. L. Electrical properties of single crystals of indium oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 33, 2834–2840(1962).

Mizuno, M., Miyamoto, Y., Ohnishi, T. & Hayashi, H. Effects of tin doping and oxygen vacancies on the electronic states of indium oxide. Jpn. J. Appl Phys. 36, 3408–3413(1997).

Gan, J. Y. et al. Vertically aligned In2O3 nanorods on FTO substrates for photoelectrochemical applications. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 14685–14692(2011).

Cronemeyer, D. C. & Gilleo, M. A. The optical absorption and photoconductivity of Rutile. Phys. Rev. 82, 975–976(1951).

Kim, W. T., Kim, C. D. & Choi, Q. W. Sub-band-gap photoresponse of TiO2-x thin-film electrolyte interface. Phys. Rev. B 30, 3625–3628(1984).

Acknowledgements

Y.X.T. acknowledges the financial support of this work by the Natural Science Foundations of China (90923008 and J1103305) and the Natural Science Foundations of Guangdong Province (92510275010 00002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y.G. and X.H.L. contributed equally to this work. The experiments were designed by J.Y.G. with suggestions from Y.X.T. and X.H.L.; J.Y.G. and S.C.I.W prepared In2O3 materials. M.H.Y. Z.S.Z. and J.Y.G. performed electron microscopy studies. X.H.L., S.L.X. and T.Z. performed PEC measurements. Y.C.M. performed XPS analysis. J.W. and Y.S. performed the theoretical calculations. J.Y.G., X.H.L. and Y.X.T. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supporting information revised

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gan, J., Lu, X., Wu, J. et al. Oxygen vacancies promoting photoelectrochemical performance of In2O3 nanocubes. Sci Rep 3, 1021 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01021

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01021

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced Catalytic Performance of Carbon Nitride-Functionalized Titanium Dioxide through Efficient Oxygen Vacancy Defect Engineering for Electrochemical Recognition of Epinephrine

Electrocatalysis (2024)

-

SrHfO3:Cr3+ Perovskite Microcubes for Rare-Earth-Free NIR-I Light Emission

Journal of Electronic Materials (2024)

-

Performance Improvement of a-In-Ga-Sn-O Thin-Film Transistor with Oxygen Doping by Reactive Sputtering Method

Journal of Electronic Materials (2024)

-

Performance of alkali and Cu-modified ZSM-5 during catalytic ozonation of polyvinyl alcohol in aqueous solution

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Enhanced UV Light–Driven Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue by Fe-Doped SnO2 Nanoparticles

Brazilian Journal of Physics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.