Abstract

Thermally reduced graphene nanoplatelets were covalently functionalised via Bingel reaction to improve their dispersion and interfacial bonding with an epoxy resin. Functionalised graphene were characterized by microscopic, thermal and spectroscopic techniques. Thermal analysis of functionalised graphene revealed a significantly higher thermal stability compared to graphene oxide. Inclusion of only 0.1 wt% of functionalised graphene in an epoxy resin showed 22% increase in flexural strength and 18% improvement in storage modulus. The improved mechanical properties of nanocomposites is due to the uniform dispersion of functionalised graphene and strong interfacial bonding between modified graphene and epoxy resin as confirmed by microscopy observations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mother of all graphitic materials, graphene is a single layer of sp2 carbon atoms and is the building block for all carbon allotropes such as fullerene and carbon nanotubes. Since the advent of graphene in 20041, the scientific community interest in graphene and graphene based materials has grown exponentially and the number of publications increased dramatically2. This interest mainly stems from a combination of incredible mechanical, electrical and thermal properties of graphene. Before graphene, another famous carbon family member- carbon nanotubes had attracted numerous attention however recent studies have shown that graphene could surpass the properties of carbon nanotubes2. This is attributed to the incredibly high specific surface area, unique graphitised plane structure and extremely high charge mobility of graphene3.

In order to improve the properties of polymers, graphene based sheet has been incorporated both into thermosetting4,5,6,7,8 and thermoplastic polymers9,10,11,12. Similar to inclusion of other nanofillers such as clay and CNTs and regardless of polymer matrix used, the challenge in processing of graphene reinforced composites is to achieve a strong interface and a uniform dispersion of graphene nanoplatelets within polymer matrix13. The true realization of remarkable properties of graphene could only happen if graphene nanoplatelets are well dispersed in matrix and that there is a strong interfacial adhesion between graphene nanoplatelets and polymer matrix14.

To this end, efforts have been made to develop approaches to tackle processing issues associated with graphene based materials. Chemical functionalization of graphene could facilitate uniform dispersion and improve compatibility with polymer matrices. In addition, chemical functionalization allows tunning of the chemical and physical properties of resulting materials which may give rise to novel properties15,16. Chemical functionalization of graphene has been achieved through covalent and non-covalent bonding of various organic functional groups such as isocyanate17, polystyrene18, polyglycidyl methacrylate19, triphenylene4, dopamine20. While in covalent functionalization approach functional groups form chemical bonds with the group presenting on graphene surface, non-covalent functionalization method is mainly based on weak van der waals force or π-π interaction of aromatic molecules on the graphene basal plane and non-covalent functional groups. Although non-covalent attachment avoids the interruption of graphitic planes in graphene giving rise to less defect sites, covalent functionalization ensures a strong and irreversible bond between the polymer matrix and graphene14.

Among various approaches to covalent functionalization of graphene surface, cycloaddition reaction has been successfully applied for the organic functionalization of carbon based nanostructures including chemically converted graphene21,22. The significance of this chemistry method lies in its versatility in introducing organic derivatives which enables application in biotechnology, energy and polymer composites23,24. Herein we report organic functionalization of thermally reduced graphene via Bingel reaction which is an example of 2,1-cycloaddition reaction. The Bingel cyclopropanation has been commonly employed for the functionalization of fullerenes25 and single walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs)26,27.

More recently, solution exfoliated graphite was chemically modified using Bingel reaction with the aid of sonication and microwave irradiation which led to highly functionalised graphene with good dispersability in organic solvents28. Despite the ease of Bingel reaction conditions, to date very few studies if any applied cyclopropanation reaction on thermally reduced graphene and investigated the influence of resulting functionalised graphene on composite properties.

In the present work, thermally reduced graphene was functionalised using Bingel reaction and the Bingel modified graphene was incorporated into epoxy resin. The morphology and mechanical properties of Bingel functionalised graphene/epoxy composites were investigated to evaluate the effect of chemical functionalization on the dispersion status and interface in the resulting composites.

Experimental

Materials

Natural flake graphite used in this study was kindly provided by Asbury Carbons (grade 3243). All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Both Epon 862 epoxy resin (Bisphenol F) and Epikure W aromatic amine curing agent were purchased from Hexion Specialty Chemicals.

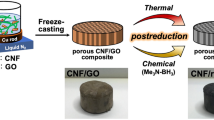

Preparation and chemical functionalization of graphene

Natural flake graphite was oxidised in a solution of nitric acid, sulphuric acid and potassium chlorate for 96 h29. Graphene oxide (GO) was dried in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 24 h. Vacuum dried GO was placed in a quartz tube and flushed with Ar for 10 min. The quartz tube was then quickly inserted into a Lindberg tube furnace preheated to 1050°C and held in the furnace for 30 s30 to obtain thermally reduced graphene (TRG). Functionalisation of TRG was conducted according to Bingel reaction reported by Coleman and co-workers26. A suspension of TRG in dry dichlorobenzene (DCB) was prepared by sonication. A mixture of 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undecene (DBU) and diethylbromomalonate were added and stirred under inert atmosphere for 15 h. The mixture was filtered and washed with DCB followed by ethanol. The resulting product was dispersed and stirred in a mixture of NaOH, methanol and THF and stirred at room temperature and was then centrifuged31. The supernatant solution was discarded and the sample was dispersed in HCl solution at room temperature. The mixture was centrifuged and washed a few times by distilled water. The functionalised graphene hereafter denoted as FG, was then dried at 60°C for 5 h in vacuum oven. The synthesis method is illustrated in Figure 1.

Composite preparation

Graphite nanoplatelets (0.1 wt%) were dispersed in acetone (~1 mg/ml) using a probe sonicator (1000 W, 20 KHz) for 30 min. The epoxy resin was then added and the suspension was ultrasonicated for one more hour. During the ultrasonication, the mixture was kept cool by an ice bath. To remove acetone, the above mixture was heated at 70°C while constantly stirring before heating in a vacuum oven at 70°C for 8 hours. Epicure W curing agent was then added and the mixture was degassed with stirring under vacuum at room temperature for 30 min. The mixing ratio of the epoxy and curing agent was 100:26.4 as recommended by the manufacturer. To fabricate nanocomposite samples, this mixture was poured into a preheated Teflon mould and cured in an oven at 120°C for 2 hours followed by 2 hours post curing at 177°C. Neat epoxy samples were prepared using the same procedure.

Measurements and characterisations

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded by a FTIR spectrophotometer (Bruker Optics) using the KBr method. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained by a Zeiss supra 55VP4 scanning electron microscope. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was measured under a nitrogen atmosphere using a Perkin Elmer at a heating rate of 5°C/min. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained by a JEOL 2100 microscope. Wide angle X-ray diffractometry (XRD) data were collected using a Panalytical XRD instrument with Cu radiation 1.5406 Å. Raman measurements were performed at room temperature at 514 nm. Three-point bending flexural tests were conducted according to ASTM D790 using a Lloyd tensile tester. Dimensions of specimen were 70 mm (length) × 10 mm (width) × 3.3 mm (thickness). The tests were performed with a 10 kN load cell at a cross-head speed of 2 mm/min. At least five specimens from each sample were tested. Dynamic mechanic analysis (DMA) was performed on a TA Instruments Q800 in the cantilever bending mode at a frequency of 1 Hz. Typical dimension for DMA sample were 56 mm (length) × 13 mm (width) × 3 mm (thickness). Measurements were carried out from 30°C to 180°C at a heating rate of 2°C/min and a strain of 0.05%.

Results and Discussion

The morphologies of starting materials as well as thermally reduced graphene (TRG) and functionalised graphene (FG) were characterised using TEM and SEM as shown in Figure 2. A representative TEM image of TRG is shown in Figure 2a. TRG exhibits transparent and wrinkled sheet structure which is due to the epoxy groups forming chains across the graphene surface32. No obvious morphological changes were observed for FG (Figure 2b) indicating that chemical functionalization process did not result in restacking and agglomeration of graphene layers. High resolution TEM (Figure 2c) demonstrates that the TRG composed of ~4–5 individual graphene sheets within each platelet. Figure 2d presents the SEM image of natural flake graphite. As shown graphite flakes demonstrate a layered structure and graphite sheets are stacked densely. As shown in Figure 2e graphene oxide has been successfully reduced to graphene nanoplatelets and presents a typical rippled structure that has been preserved through chemical functionalization (Figure 2f).

Figure 3 shows XRD patterns of the graphite, GO, TRG and FG. The graphite exhibits a sharp diffraction peak centered at 2θ = 26.5° corresponding to the (0 0 2) graphite plane composed of well-ordered graphenes with an interlayer spacing of 3.35 Å. This peak disappears for GO and a relatively low peak at 2θ = 10.5° appears, corresponding to the diffraction of the (0 0 2) graphite oxide plane. The interlayer spacing of GO is calculated according to the Bragg's law and the calculated value is 8.41 Å. This implies that as graphite transforms to GO most oxygen atoms are bonded to the graphite surface and that graphite is expanded when oxidized19,33. After high temperature heat treatment, (002) peak disappears indicating that the thermally reduced graphene sheets are disordered. Removal of oxidised functional groups results in exfoliation to graphene nanosheets, which was further confirmed by TEM. The randomly disordered graphene XRD patterns remains unchanged after functionalization indicating that chemical functionalization process did not give rise to restacking of graphene layers.

In the FT-IR spectrum of the graphene oxide sample (Figure 4), the peaks at ~3432 and 1711 cm−1 are attributed to –OH and C = O bands, respectively. Upon reduction of graphene oxide to graphene, the C = O band disappears and new bands at 2928 and 2865 cm−1 arise representing the C-H stretch vibrations of the methylene group. Functionalised graphene displays a peak at 1731 cm−1 characteristic band for C = O stretch of the COOH group. The presence of carboxylic functional group is further confirmed by the strong and broad band at 3412 cm−1.

Raman spectroscopy is employed to study the transformation of graphite to graphene and functionalised graphene. Raman spectra of graphite, graphene and functionalised graphene are shown in Figure 5. In the graphite spectra there is a Raman active bond which is the vibrational G band at 1578 cm−1 representing in-plane bond stretching vibration of sp2 bonded carbon atoms34. There are significant structure changes in thermally reduced graphene leading to appearance of D band at 1342 cm−1 indicating the presence of defects due to oxidation and thermal reduction of graphite. The G band in thermally reduced graphene slightly shifts to lower frequencies and shows higher intensity and broadened and the D band appears which demonstrates an increased D/G intensity ratio of 0.70 compared to 0.05 in graphite. In functionalised graphene D band becomes broad and there is a further increase in D/G intensity ratio, from 0.05 of graphite to 0.90 which confirms the successful attachment of functional groups on graphene nanosheets. Also, the G band shifts back to the position of the G band in graphite that could be attributed to the graphitic self-healing as previously reported in literature35.

TGA is a valuable and fairly simple method in investigating the thermal stability as well as further analysing the presence of functional group in carbonaceous materials. As seen in Figure 6, graphite is a thermally stable material with no weight loss over the entire testing temperature range. GO, however, has a slight initial mass loss at ~100°C which could be attributed to the evaporation of water molecules36,37. The main weight loss (~40%) for GO takes place at ~220°C and is attributed to the pyrolysis of the reactive oxygen containing functional groups, yielding CO2, CO and H2O vapors. This is in agreement with findings of other researchers17,38. Functionalised graphene on the other hand has a significantly higher thermal stability than GO with the main weight loss occurring at about 500°C. Higher onset degradation temperature for functionalised graphene compared to GO could be due to the presence of more stable oxygen containing functional groups. TRG is thermally stable up to ~600°C, with the overall weight loss of ~16% at 800°C. It's been suggested in previous studies that thermal reduction of graphite oxide restores the graphitic structure resulting in a more thermally stable material39. Due to excellent thermal properties, graphene is used for thermal management of various materials40.

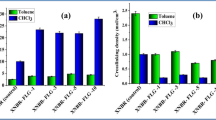

The three point bending or flexural test is a useful and commonly used test due to the mixture between tensile and compressive forces that are likely to be encountered in the real world application of composites. This test was done to investigate how the addition of FG influences the mechanical properties of epoxy matrix. Samples with 0.1 wt% TRG and FG as well as neat epoxy were prepared and tested for flexural properties. Figure 7 shows strain-stress plots for neat epoxy and composites containing TRG and FG. The addition of TRG and FG shows the increase in flexural strength of epoxy matrix by ~15% and 22%, respectively. As shown in TEM images, TRG exhibit a wrinkled topology due to extremely small thickness. Nanoscale surface roughness and wrinkled nature of TRG enhances mechanical interlocking leading to better adhesion41. The presence of carboxylic functional group on FG which may form covalent bonding with epoxy matrix further improves the interfacial bonding with epoxy leading to further improvement in mechanical properties.

In order to obtain more information regarding the interfacial adhesion between FG and epoxy matrix, fractured surface of epoxy samples containing TRG and FG was further studied using SEM imaging and is shown in Figure 8. As can be seen from Figure 8a, the epoxy composite containing TRG exhibits a relatively smooth fracture surface with river-like patterns in the direction of fracturing force, a brittle failure as a result of weak bonding between TRG and epoxy. In examining SEM images (not shown here) we also found that the fracture surface of epoxy/TRG is not uniform meaning that in some regions the surface is mirror-like. This can suggest irregular distribution and dispersion of TRG within poxy matrix. The incorporation of FG into epoxy matrix exhibits different feature and fracture surface morphology (Figure 8b). The fracture surface of FG/epoxy composites is rough with many small faceted features. This further suggests that the strong interfacial adhesion between functionalised graphene and epoxy matrix discourage fracture, leading to a rough surface. As shown in red circles in Figure 8c, functionalised graphene platelets are embedded in epoxy matrix. No obvious pull out can be observed and the epoxy matrix appears to sufficiently wet the graphene surface (Figure 8d) which suggests that FG present strong filler-matrix interfacial bonding and encourages dispersion as a result of chemical functional group present on the surface of graphene. Strong interface and improved dispersion have a significant influence on the mechanical properties of composites42.

Figure 9a shows the tan delta plot for neat epoxy and epoxy composites containing TRG and FG. The peak of tan delta curve is considered as glass transition temperature (Tg) of polymers. Neat epoxy resin shows a Tg of 153.9°C. With the addition of TRG and FG, Tg increases to 167.6 and 169.8°C, respectively. The rise in Tg upon inclusion of nanofillers is often associated with a restriction in molecular motion and higher degree of crosslinking indicating significant changes in polymer chains dynamics43,44. In addition to this, molecular dynamic studies have confirmed that surface geometry of nanofillers could influence polymer mobility45. Therefore, it's plausible that the nanoscale surface roughness and wrinkled nature of graphene surface induce interfacial interactions through mechanical interlocking with polymer chains and hinder molecular mobility leading to increase in Tg upon addition of TRG and FG. On the other hand, the presence of carboxylic functional group on the surface of graphene enhances uniform dispersion within resin matrix which in turn leads to creating an interphase zone surrounding FG nanoplatelets. This increased surface area in contact with resin together with formation of covalent bonds between FG and epoxy matrix, constrains the resin matrix chain mobility even further and results in a larger Tg shift. Higher Tg in epoxy/FG composites reflects the more effective chain restriction ability of FG. The higher peak height of tan delta for epoxy/FG composites compared to epoxy/TRG could also indirectly indicates a uniform dispersion of the FG in the epoxy resin46.

The storage modulus plots for neat epoxy matrix and composites containing TRG and FG are presented in Figure 9b. The storage modulus in composite containing nanofillers is highly influenced by the interfacial bonding strength between reinforcement filler and resin matrix47. Inclusion of TRG and FG into neat epoxy demonstrates an increase in storage modulus in the glassy region. The storage modulus of epoxy at 30°C is 2.25 GPa and that of nanocomposite containing TRG and FG is 2.44 and 2.61 GPa, respectively. This indicates about 10% and 18% increase, respectively, compared to the neat epoxy. The two dimensional sheet geometry of TRG and its high aspect ratio enables effective load transfer. FG forms a strong interface interaction with the epoxy matrix as a result of functional groups present in its chemical structure. Covalent bonding between carboxylic group of FG and epoxy could improve the load transfer and consequently enhance the reinforcing effect. As the temperature increases, the storage modulus falls, indicating energy dissipation which occurs during the transition of the glassy state to a rubber state. Investigating the storage modulus in rubbery region i.e higher temperature, it is noted that the storage modulus for the composite samples containing FG is the highest of the three. At 135°C the storage modulus of the FG/epoxy composite is about 2.7 times higher than both the neat epoxy and TRG reinforced samples.

Conclusions

In this study, we reported covalent functionalization of thermally reduced graphene through Bingel reaction. The reaction conditions provided a platform for functional groups to covalently attach onto the graphene skeleton. Bingel modified graphene showed a randomly disordered structure with enhanced thermal stability. Functionalised graphene were homogenously dispersed in epoxy resin to produce nanocomposites. Nanocomposite containing a small functionalised graphene loading demonstrated improved flexural strength and modulus. The incorporation of functionalised graphene enhanced the glass temperature of epoxy resin. This shift along with improved mechanical properties suggests stronger interfacial interactions between graphene and epoxy as a result of chemical modification of thermally reduced graphene. Further investigations into the properties of epoxy composites containing various concentrations of Bingel modified graphene is currently underway and will be reported in future.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Singh, V. et al. Graphene based materials: Past, present and future. Prog Mate Sci 56, 1178–1271 (2011).

Geim, A. K. Graphene: Status and prospects. Science 324, 1530–1534 (2009).

Wan, Y. J. et al. Improved dispersion and interface in the graphene/epoxy composites via a facile surfactant-assisted process. Compos Sci Technol 82, 60–68 (2013).

Fang, M. et al. Constructing hierarchirally structured interphases for strong and tough epoxy nanocompostes by amine-rich graphene surfaces. J Mater Chem 20, 9635–9643 (2010).

Jovic, N. et al. Temperature dependence of the electrical conductivity of epoxy/expanded graphite nanosheet composites. Scripta Mater 58, 846–849 (2008).

Li, J., Sham, M. L., Kim, J. K. & Marom, G. Morphology and properties of UV/ozone treated graphite nanoplatelet/epoxy nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol 67, 296–305 (2007).

Tang, L.-C. et al. The effect of graphene dispersion on the mechanical properties of graphene/epoxy composites. Carbon 60, 16–27 (2013).

Ye, L., Meng, X. Y., Ji, X., Li, Z. M. & Tang, J. H. Synthesis and characterization of expandable graphite-poly(methyl methacrylate) composite particles and their application to flame retardation of rigid polyurethane foams. Polym Degrad Stabil 94, 971–979 (2009).

Kalaitzidou, K., Fukushima, H. & Drzal, L. T. Mechanical properties and morphological characterization of exfoliated graphitepolypropylene nanocomposites. Compos Part A 38, 1675–1682 (2007).

Wakabayashi, K. et al. Polymer-graphite nanocomposites: effective dispersion and major property enhancement via solid-state shear pulverization. Macromolecules 41, 1905–1908 (2008).

Kim, H., Hahn, H. T., Viculis, L. M., Gilje, S. & Kaner, R. B. Electrical conductivity of graphite/polystyrene composites made from potassium intercalated graphite. Carbon 45, 1578–1582 (2007).

Kuilla, T. et al. Recent advances in graphene based polymer composites. Prog Polym Sci 35, 1350–1375 (2010).

Layek, R. K. & Nandi, A. K. A review on synthesis and properties of polymer functionalised graphene. Polymer 54, 5087–5103 (2013).

Chua, C. K. & Pumera, M. Covalent chemistry on graphene. Chem Soc Rev 42, 3222–3233 (2013).

Georgakilas, V. et al. Functionalization of Graphene: Covalent and Non-Covalent Approaches, Derivatives and Applications. Chem Rev 112, 6156–6214 (2012).

Stankovich, S. et al. Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 442, 282–286 (2006).

Wang, G., Shen, X., Wang, B., Yao, J. & Park, J. Synthesis and characterisation of hydrophilic and organophilic graphene nanosheets. Carbon 47, 1359–1364 (2009).

Teng, C.-C. et al. Thermal conductivity and structure of non-covalent functionalized graphene/epoxy composites. Carbon 49, 5107–5116 (2011).

Xu, L. Q., Yang, W. J., Neoh, K. G., Kang, E. T. & Fu, G. D. Dopamine-induced reduction and functionalization of graphene oxide nanosheets. Macromolecules 43, 8336 (2010).

Georgakilas, V. et al. Organic functionalisation of graphene. Chem Comm 46, 1766–1768 (2010).

Quintana, M. et al. Functionalization of Graphene via 1,3- Dipolar Cycloaddition. ACS Nano 4, 3527–3533 (2010).

Georgakilas, V. et al. Multipurpose Organically Modified Carbon Nanotubes: From Functionalization to Nanotube Composites. J Amer Chem Soc 130, 8733–8740, 10.1021/ja8002952 (2008).

Kostarelos, K. et al. Cellular uptake of functionalized carbon nanotubes is independent of functional group and cell type. Nat Nano 2, 108–113 (2007).

Diederich, F. & Thilgen, C. Covalent Fullerene Chemistry. Science 271, 317–324 (1996).

Coleman, K. S., Bailey, S. R., Fogden, S. & Green, M. L. H. Functionalisation of single-walled carbon nanotubes via the bingle reaction. J Amer Chem Soc 125, 8722–8723 (2003).

Tasis, D., Tagmatarchis, N., Bianco, A. & Prato, M. Chemistry of Carbon Nanotubes. Chem Rev 106, 1105–1136 (2006).

Economopoulos, S. P., Rotas, G., Miyata, Y., Shinohara, H. & Tagmatarchis, N. Exfoliation and Chemical Modification Using Microwave Irradiation Affording Highly Functionalized Graphene. ACS Nano 4, 7499–7507 (2010).

Hummers, W. S. & Hoffman, R. E. Prepartion of graphitic oxide. J of Amer Chem Soc 80, 1339 (1958).

Schniepp, H. C. et al. Functionalized Single Graphene Sheets Derived from Splitting Graphite Oxide. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 110, 8535–8539 (2006).

Assefa, H., Nimrod, A., Walker, L. & Sindelar, R. Enantioselective synthesis and complement inhibitory assay of A/B-ring partial analogues of oleanolic acid. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 11, 1619–1623 (2001).

Sengupta, R., Bhattacharya, M., Bandyopadhyay, S. & Bhowmick, A. K. A review on the mechanical and electrical properties of graphite and modified graphite reinforced polymer composites. Prog Polym Sci 36, 638–670 (2011).

Dikin Dmitriy, A. et al. Preparation and characterization of graphene oxide paper. Nature 448, 457–460 (2007).

Liu, Y., Deng, R., Wang, Z. & Liu, H. Carboxyl-functionalized graphene oxide–polyaniline composite as a promising supercapacitor material. J Mater Chem 22, 13619–13624 (2012).

Liu, H.-H., Peng, W.-W., Hou, L.-C., Wang, X.-C. & Zhang, X.-X. The production of a melt spun functionalized graphene/poly (ε-caprolactam) nanocomposite fiber. Compos Sci and Technol 81, 61–68 (2013).

Stankovich, S. et al. Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. Carbon 45, 1558–1565 (2007).

Park, S. et al. Hydrazine-reduction of graphite- and graphene oxide. Carbon 49, 3019–3023 (2011).

Pardes, J. I., Villar-Rodil, S., Martinez-Alonso, A. & Tascon, J. M. D. Graphene oxide dispersions in organic solvents. Langmuir 24, 10560–10564 (2008).

Shen, J., Hu, Y., Li, C., Qin, C. & Ye, M. Synthesis of amphiphilic graphene nanoplatelets. Small 5, 82–85 (2009).

Amini, A. et al. Temperature variations at nano-scale level in phase transformed nanocrystalline NiTi shape memory alloys adjacent to graphene layers. Nanoscale 5, 6479–6484 (2013).

Ramanathan, T. et al. Functionalized graphene sheets for polymer nanocomposites. Nature Nanotech 3, 327–331 (2008).

Gudarzi, M. M. & Sharif, F. Enhancement of dispersion and bonding of graphene-polymer through wet transfer of functionalized graphene oxide. eXPRESS Polym Lett 6, 1017–1031 (2012).

Ganguli, S., Roy, A. K. & Anderson, D. P. Improved thermal conductivity for chemically functionalised exfoliated graphite/epoxy composites. Carbon 46, 806–817 (2008).

Fang, M., Wang, K., Lu, H., Yang, Y. & Nutt, S. Covalent polymer functionalisation of graphene nanosheets and mechanical properties of composites. J Mater Chem 38, 7098–7105 (2009).

Smith, G. D., Bedrov, D., Li, L. & Byutner, O. A molecular dynamics simulation study of the viscoelastic properties of polymer nanocomposites. J Chem Phys 20, 9478–9489 (2002).

Zhou, Y., Pervin, F., Lewis, L. & Jeelani, S. Experimental study on the thermal and mechanical properties of multi-walled carbon nanotube-reinforced epoxy. Mater Sci Eng: A 452, 657–664 (2007).

Wang, S., Liang, Z., Liu, T., Wang, B. & Zhang, C. Effective amino-functionalisation of carbon nanotubes for reinforcing epoxy polymer composites. Nanotechnology 17, 1551–1557 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The research was supported under the Deakin University Central Research Grant Scheme awarded to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: M.N. Performed the experiments: M.N., J.W., A.A., H.K., N.H. and L.L. Data analysis: M.N. and J.W. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: M.N., Y.C. and B.F. Wrote the manuscript: M.N. All authors contributed to the technical review of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Naebe, M., Wang, J., Amini, A. et al. Mechanical Property and Structure of Covalent Functionalised Graphene/Epoxy Nanocomposites. Sci Rep 4, 4375 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04375

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04375

This article is cited by

-

Surface Plasmon Resonance-based Ultra-broadband Solar Thermal Absorber Design Using Graphene Material

Plasmonics (2024)

-

Dynamic analysis of thermally affected nanocomposite plates reinforced with functionalized graphene oxide nanoparticles

Acta Mechanica (2024)

-

Preparation of Poly (styrene-methyl acrylate) Reinforced on Ag-rGO Nanocomposite Under Photocatalytic Conditions and Its Use as a Hybrid Filler for Reinforcement of Epoxy Resin

Topics in Catalysis (2024)

-

A three-dimensional hybrid of CdS quantum dots/chitosan/reduced graphene oxide-based sensor for the amperometric detection of ceftazidime

Chemical Papers (2023)

-

Novel Ternary Epoxy Resin Composites Obtained by Blending Graphene Oxide and Polypropylene Fillers: An Avenue for the Enhancement of Mechanical Characteristics

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.