Abstract

The cost-effectiveness of market-dominating silicon wafer solar cells plays a key role in determining the competiveness of solar energy with other exhaustible energy sources. Reducing the silicon wafer thickness at a minimized efficiency loss represents a mainstream trend in increasing the cost-effectiveness of wafer-based solar cells. In this paper we demonstrate that, using the advanced light trapping strategy with a properly designed nanoparticle architecture, the wafer thickness can be dramatically reduced to only around 1/10 of the current thickness (180 μm) without any solar cell efficiency loss at 18.2%. Nanoparticle integrated ultra-thin solar cells with only 3% of the current wafer thickness can potentially achieve 15.3% efficiency combining the absorption enhancement with the benefit of thinner wafer induced open circuit voltage increase. This represents a 97% material saving with only 15% relative efficiency loss. These results demonstrate the feasibility and prospect of achieving high-efficiency ultra-thin silicon wafer cells with plasmonic light trapping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Being the dominant products on the photovoltaic market, crystalline Si wafer solar cells have been the intensive research focus for years1. Increasing the energy conversion efficiency and reducing the cost have been the two major driving forces for the solar industry and academic research to make solar electricity more competitive with the conventional fossil fuel. An effective way of cost reduction is to make the wafer thinner since the wafer cost accounts for approximate 50% of the solar cell cost2. In the past few decades, the wafer thickness has been reduced from 400 μm to the current 180 μm and the trend of reduction is continuing2. Apart from the cost saving consideration, thinner wafer can potentially lead to a higher open circuit voltage, Voc, due to the lower bulk recombination and more efficient electron-hole pair extraction3,4,5,6,7.

However, the wafer thickness reduction poses a great challenge for efficiency maintenance due to the significant light absorption decline at the longer wavelengths, especially when the wafer thickness is reduced to below 50 μm8. The longer wavelength light has a lower absorption coefficient, requiring a larger travelling distance in Si to be completely absorbed. To fully appreciate the benefits of wafer-thickness-reduction-induced cost savings and higher electrical performance, advanced light trapping technology targeting the longer wavelength region of the solar spectrum is pressingly required to be developed.

Metallic nanoparticles, which support localized surface plasmons, have been demonstrated to be able to provide advanced light trapping mechanisms to significantly enhance the light absorption in solar cells by the scattering and near-field effects9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. So far, most of the plasmonic solar cell research has been focused on the thin film technology11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Only limited work has been conducted on Si wafer solar cells using Ag or Al nanoparticles due to the fact that thick silicon wafer cells absorbs almost 90% of the sun light higher than the bandgap19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. There is limited room to further increase. However, as the wafer thickness reduces, the nanoparticles are expected to play an increasingly important role.

In this manuscript, through theoretically exploring the maximum potential of the light absorption that can be achieved by metallic nanoparticle arrays within the Si wafer solar cells, we find that plasmonics light trapping plays a pivotal role in the efficiency enhancement of ultra-thin wafer cells of thickness down to 1 μm. We further identify that the critical design parameters of the ordered nanoparticle array for maximum light absorption enhancement are wafer-thickness dependent. Furthermore, we experimentally verify the large absorption enhancement within ultra-thin Si wafers by plasmonic nanoparticles. The insights in this article open up a new perspective and guidance for achieving high efficiency wafer solar cells at the ultra-thin Si thickness.

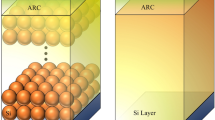

Fig. 1a shows the thick 180 μm solar cell with a standard configuration (cell without nanoparticles) used throughout this study, consisting of a 75 nm SiNx antireflection coating (ARC) layer on the surface of a Si wafer. 75 nm is the optimized thickness for SiNx as an ARC layer. An optically thick Al back reflector is located underneath the wafer. Figs. 1b and 1c identify, respectively, the ultra-thin solar cells with the light trapping nanoparticles located on the front surface of the SiNx ARC and embedded in a SiO2 dielectric layer positioned between the Si wafer and the Al back reflector. The front nanoparticles can both reduce the light reflection at the front surface due to the optical impedance matching and the light path length increase particularly for the longer wavelengths as a result of the scattering induced angular redistribution of the incident light. The rear nanoparticles also can enhance the light path lengths by scattering. In addition, the scattered light with angles larger than the critical angle of the front interfaces can be trapped inside the Si due to total internal reflection. To avoid the transmittance reduction introduced by the surface plasmon polariton at the longer wavelengths28, spherical nanoparticles are used on the front surface to minimize the contact area between the metallic nanoparticles and the substrate, while hemispherical nanoparticles are used on the rear side of the cells due to a better coupling of the scattered light into the Si layer21. The SiO2 spacing layer between the Si and Ag nanoparticles is 20 nm, which is a balance between light incoupling and rear surface passivation21. Another 100 nm SiO2 layer is designed under the nanoparticles, for electrical isolation.

Concept of plasmonics nanoparticle (NP) enabled ultra-thin high-efficiency Si wafer solar cells.

(a) A standard 180 μm solar cell, consisting of a 75 nm SiNx antireflection coating (ARC) layer, the Si layer and the Al back reflector. Ultra-thin solar cell with (b) the spherical NPs located on the front surface of the SiNx ARC and (c) the hemispherical NPs embedded in a SiO2 layer between the Si layer and the Al back reflector.

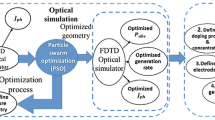

Fig. 2 shows the optical simulated results of the solar cells. The finite difference time domain (FDTD) method (FDTD Solutions, Lumerical) was used to investigate the light absorption in the Si layer of the three cell designs in Fig. 1 at the wafer thicknesses of 180, 100, 50, 20, 10, 5, 2 and 1 μm. Perfectly matched layers were used in the vertical direction to avoid the interference of the light reflected from the simulation boundaries and periodic boundary conditions were used in the lateral direction to simulate an ordered array of nanoparticles. A plane wave source ranging from 300 nm to 1200 nm was employed. Refractive index data for metallic nanoparticles were obtained from Palik29, crystalline Si from Green30 and SiNx data was measured from a commercial solar cell. Transmission monitors were employed on the front and rear surfaces of the Si layer to obtain the light transmission into and out of the Si layer thereby the light absorption. The integrated light absorption was calculated by integrating the light absorption over the spectrum and weighting to the AM1.5 standard solar photon spectrum in the 300–1200 nm spectral range. The particle diameter, D and the coverage, C, were investigated for each design at different wafer thicknesses.

Optical simulations by FDTD.

(a) Integrated light absorption in the Si layers of the plasmonic solar cell designs referenced to the standard solar cells as a function of the wafer thickness. The horizontal dash line shows the integrated absorption for a 180 μm standard wafer cell. (b) Light absorption spectrum in Si for 50 μm wafer cells with the optimized rear Ag NPs, referenced to the standard 180 μm and 50 μm wafer cells. (c) Integrated absorption enhancement at each wafer thickness for the optimized front Al, Ag NPs and the optimized rear Ag NPs, respectively. (d) Light absorption spectrum in Si for the 180 μm wafer cells in the cases of standard structure, front Al NPs and rear Ag NPs. The oscillations in the longer wavelengths are due to the interference effect in the simulation.

Two metals, Al and Ag, were selected as the front located nanoparticle materials for light trapping while Ag nanoparticles for rear light trapping. Al nanoparticles, with their surface plasmon resonances located in the UV region below the usable solar spectrum edge at 300 nm, have been demonstrated to be able to avoid the light incoupling loss and introduce an extra enhancement in the shorter wavelength range24,25. Ag nanoparticles, however, have larger scattering strength and less particle absorption than the Al nanoparticles at the longer wavelengths. Therefore it is expected that the optimized material for the front located nanoparticles might switch from Al to Ag when the wafer thickness reduces to a certain extent where the light trapping for the longer wavelengths is predominant. While Ag is the best material for the rear side since the only consideration is the longer wavelength light trapping.

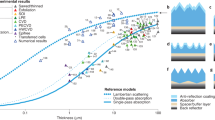

Fig. 2a shows the integrated light absorption of the optimized plasmonic nanoparticle enhanced solar cells for different wafer thicknesses, referenced to the standard cell structure, with the detailed data in Supplementary Information. The reduction in the wafer thickness of the standard cells leads to a dramatic absorption decline from around 80% (180 μm) to 33% (1 μm). By using plasmonic nanoparticles either on the front or the rear side of the wafer cells, the light absorption is largely enhanced, with more significant enhancement from the rear located Ag nanoparticles at each wafer thickness. We observe that the integration of rear located Ag nanoparticles allows the wafer thickness to be significantly reduced to 50 μm without a compromise in the light absorption compared to that of the 180 μm standard cell, as indicated in the dashed lines in Fig. 2a. This is further confirmed by the absorption spectrum of the 50 μm wafer cells with rear Ag nanoparticles and the 180 μm standard cells, shown in Fig. 2b. The additional nanoparticle-induced light trapping mechanism completely compensates for the light absorption decline in the wavelengths longer than 800 nm caused by the wafer thickness reduction from 180 μm to 50 μm.

Fig. 2c shows the enhancement of the integrated absorption as a function of the wafer thickness for the optimized particles, relative to the standard cells. For front nanoparticles, it is found that Al is preferred when the Si thickness is above 5 μm with a stable enhancement of approximately 2% whereas Ag outperforms Al for wafer thicknesses of 2 and 1 μm, with enhancements up to 4.7% and 8.6%, respectively. As expected, we observe that the optimized material switches from Al to Ag when the wafer thickness reduces to below 5 μm where longer wavelength light trapping plays a key role in the absorption enhancement. Compared with the front surface nanoparticles, the enhancement of the rear nanoparticles increases from 5.2% to 24.4% when the thickness of Si wafer reduces from 180 μm to 1 μm. We show in Fig. 2d that the absorption spectrum of the 180 μm wafer cell with a standard structure, front integrated Al nanoparticles and rear integrated Ag nanoparticles, individually. Front Al nanoparticles lead to enhancements at both the wavelengths shorter than 500 nm and wavelengths longer than 700 nm with a slight reduction at the middle wavelengths. Whereas for rear Ag nanoparticles, the light absorption at wavelengths longer than 900 nm has been enhanced without any reduction on the shorter wavelengths. This explains the larger enhancement by the rear Ag nanoparticles. Furthermore, the rear nanoparticles have a larger light incoupling efficiency than the front nanoparticles due to the presence of the Al back reflector, which can prevent the light outcoupling to the air through the rear surface.

It is noted that the optimized nanoparticle configuration (particle diameter D and particle coverage C) depends on the wafer thickness with different unabsorbed solar spectrum profiles for light trapping and the Si absorbing capabilities at different wavelengths. The optimization of the particle size is a trade-off between a few factors, including particle absorption and scattering, particle-particle intercoupling, particle-substrate incoupling et al. Small particles exhibit strong absorption and low scattering while large particles shows strong scattering and even higher order scattering modes with a comparatively small particle absorption. Increasing the size of the nanoparticles would reduce the incoupling efficiency due to the increased average distance to the substrate and redshift and broaden the plasmon resonance31. The particle coverage is determined by the scattering cross-sections of the particles and the location of the particles. A particle array with particle separation on the order of wavelength might introduce the intermediate-field hybridized modes, which would change the behavior of light scattering32.

It is interesting to note the optimized diameters of the front Al and Ag nanoparticles increase to relatively large (D > 200 nm) for thin wafers with thicknesses of 1 and 2 μm compared to the nanoparticle diameters for wafers thicker than 5 μm (see Supplementary Information). This is due to the broadband scattering cross-sections of large nanoparticles, which are beneficial for the longer wavelength light trapping. Fig. 3a shows the normalized scattering cross-sections of the optimized front located Al nanoparticles (D = 120 nm and 220 nm) and Ag nanoparticles (D = 100 nm and 240 nm) for 180 μm and 1 μm wafer cells. Clearly, the scattering cross-sections for 220 nm Al and 240 nm Ag nanoparticles are extended to the longer wavelengths compared to the narrowband scattering cross-sections for 120 nm Al and 100 nm Ag nanoparticles staying below 500 nm. The optimized C for front Al and Ag nanoparticles remained low at 10% and 5%, respectively for different wafer thicknesses above 5 μm and at 10% for 1 and 2 μm wafers, which leads to the ignorable additional cost for the final solar cells.

The optimized diameter D for rear Ag nanoparticles reduces from 240 nm to 160 nm (see Supplementary Information) when the thickness of Si wafer decreases, with the scattering cross-sections blue shifting to the shorter wavelengths (Fig. 3b) to match the broadened unabsorbed solar spectrum. The particle coverage C is found to be stabilized at 20%. The reason can be explained by the value of the normalized scattering cross-section. It is shown that the scattering cross-sections of the nanoparticles are approximately five times of the geometrical cross-sections, which means C = 20% is sufficient to fully cover the entire solar cell surface and interact adequately with the incident light.

To verify the significant absorption enhancement by the rear Ag nanoparticles, predicted by the simulation, we experimentally incorporate the Ag nanoparticles on the rear side of ultra-thin Si wafers from 50 μm to 2 μm and measured the optical responses by a UV-VIS-NIR spectrometer (Lambda 1050, Perkin Elmer) in the 300–1200 nm spectral range with an integrating sphere set up, which is used for collecting the scattered light. The SiNx ARC with a refractive index of 2.05 at 600 nm was deposited by the plasmon-enhanced chemical vapour deposition (PECVD) system at 350°C. The SiO2 space layer and Al back reflector were deposited by the e-beam evaporation. The Ag nanoparticles were formed by annealing the 18 nm thin Ag film at 200°C in the nitrogen atmosphere.

Fig. 4a shows the reflectance of 50 μm wafer with the standard and rear Ag nanoparticle light trapping structures. Broadband and large reflection suppression was achieved from 850 nm to 1200 nm. The inset figure is the SEM image of the self-assembled Ag nanoparticles, which shows a broad size distribution with averaged diameters from 50 nm to 300 nm and approximate 35% coverage. The absorption (A) in the solar cells was calculated by the relation: A = 1 − R, where R is the reflectance. It is shown in Fig. 4b that the absorption enhancement of the ultra-thin wafers expands to the short wavelength range when the wafer thickness reduces from 50 μm to 2 μm. An absorption enhancement up to 10-fold is achieved in the long wavelengths at 950 nm. It is interesting to note the oscillations in the 5 μm and 2 μm wafers. We attribute this to the Fabry-Perot resonances and the waveguide modes in the ultra-thin wafers, coupled from the scatted light by the nanoparticles14. The inset image clearly shows the optical mode distribution inside the Si for the 2 μm wafer with the optimized square array of rear located Ag nanoparticles at the 800 nm incident light. Our results demonstrate that the wave effect becomes predominant when the wafer thickness reduces to below 5 μm, where the wave-optics method needs to be employed to treat the light trapping instead of the conventional ray-optics method. It has been suggested with a further reduction of the wafer thickness to a scale comparable or smaller than the operation wavelength, the conventional Yablonovitch limit established for thick Si is potentially to be surpassed through properly designing the nanophotonics structures33,34.

Optical experiments of the ultra-thin wafers.

(a) Measured reflectance of the 50 μm Si wafers with the standard light trapping structures (75 nm SiNx ARC and Al back reflector) and the rear Ag NP light trapping, with the inset image showing the self-assembly Ag NPs (scale bar: 1 μm) (b) Absorption enhancement spectrum of the ultra-thin wafers from 50 μm to 2 μm, with the inset image showing the electrical profile at 800 nm for the 2 μm Si wafer with optimized square array of rear located Ag NPs (c) Reflectance of the two reflectors: standard reflector and the plasmonic reflector, with glass slide as superstrate for measurement (d) Experimental integrated absorption of the rear plasmonic solar cells and the standard cells, excluding the particle induced losses, in comparison with the FDTD modelling.

To exclude the light loss in the Ag nanoparticles, we measure the reflectance of the standard Al reflector and the plasmonic reflector incorporated with Ag nanoparticles using a glass slide as the superstrate. The results are shown in Fig. 4c. The gap between the two curves is the reflectance loss induced by the particles, which can be the intrinsic absorption in the particles and the plasmon losses in the rough Al back reflector. Assuming only single-bouncing reflection in the wafer, the absorption loss can be calculated by Aparticle = Tfronte−αdRloss, where Tfront is the light transmittance at the front surface of the wafer cells, α the Si absorption coefficient, d the wafer thickness, Rloss the reflectance loss induced by the particles. The integrated absorption excluding the absorption loss is shown in Fig. 4d, referenced to the FDTD simulation in Fig. 2a. The experimental result agrees remarkably well with the FDTD simulation. The small deviation is mainly attributed to the differences in the nanoparticle geometry, size and coverage and the calculation assumption of single-bouncing reflection.

The reduction of the Si thickness is expected to lead to the Voc increase for a solar cell with low surface recombination due to the increase of the generation rate of the electron-hole pairs per volume and thus the steady state of the minority carrier concentration and the split of the quasi Fermi level7. To elucidate the overall benefits of ultra-thin plasmonic wafer solar cells, we evaluate the open circuit voltage Voc of the wafer cells by the established PC1D modelling35 and calculate the short circuit current density Jsc by integrating the light absorption from the FDTD calculation with the AM 1.5 G solar spectrum, assuming a 100% electron-hole pair extraction, with the results shown in Fig. 5a. The Voc results are based on a planar cell using parameters of typical low-cost commercial products (see Supplementary Information) with surface recombination velocity at 10 cm/s, which is achievable by a variety of passivation technologies36,37,38,39. For example, the space layer SiO2 between Si and the rear contact, produced by thermally growing, could achieve this surface recombination velocity40. As shown in the figure, the Voc value increases more than 30 mV when the wafer thickness reduces to below 20 μm from 180 μm. Since the nanoparticles incorporated into the solar cells are properly isolated by the dielectric layer, no extra recombination is expected to be induced by the nanoparticles. The Jsc value of the rear plasmonic enhanced cells reduces from 39.2 mA/cm2 at 180 μm to 19.1 mA/cm2 at 1 μm, compared with 37.3 mA/cm2 for the 180 μm standard cells. The energy conversion efficiency Eff of the solar cells is calculated by  , where FF is the fill factor and Pin the incident power. Fig. 5b shows the efficiency of the rear plasmonic enhanced wafer cells, assuming a reasonable value of FF = 80%4, referenced to the standard 180 μm wafer cells. Through the curves, we can see that 20 μm plasmonic wafer cells realizes the same efficiency (Eff = 18.2%) as the 180 μm standard cells, using only around 10% of the Si material. The wafer thickness can even be further reduced to 3% (5 μm) of the current 180 μm with a reasonably high efficiency (Eff = 15.3%), which only leads to a moderate decline of approximately 15%. Unlike most of the efficiency enhancement strategies using silicon surface processing or nanostructuring, which significantly degrade the electrical property of the cells, our method has no impact on the Voc and FF and is simple and compatible with the current production procedure41.Therefore there is a high potential to play a role in the further ultra-thin wafer solar cell production.

, where FF is the fill factor and Pin the incident power. Fig. 5b shows the efficiency of the rear plasmonic enhanced wafer cells, assuming a reasonable value of FF = 80%4, referenced to the standard 180 μm wafer cells. Through the curves, we can see that 20 μm plasmonic wafer cells realizes the same efficiency (Eff = 18.2%) as the 180 μm standard cells, using only around 10% of the Si material. The wafer thickness can even be further reduced to 3% (5 μm) of the current 180 μm with a reasonably high efficiency (Eff = 15.3%), which only leads to a moderate decline of approximately 15%. Unlike most of the efficiency enhancement strategies using silicon surface processing or nanostructuring, which significantly degrade the electrical property of the cells, our method has no impact on the Voc and FF and is simple and compatible with the current production procedure41.Therefore there is a high potential to play a role in the further ultra-thin wafer solar cell production.

Electric performance evaluations of the plasmonic wafer cells.

(a) The Voc and Jsc of the rear plasmonic enhanced wafer cells as a function of the wafer thickness. The dash line shows the Jsc of the 180 μm standard wafer cells for reference. (b) The Eff of the rear plasmonic enhanced cells, referenced to the standard cells. The normalized efficiency (to the 180 μm standard wafer cells) is shown in the right axis.

In conclusion, by using advanced light trapping mechanism with simple but effective metallic nanoparticles, ultra-thin wafer solar cells with ultra-high efficiency are envisage. The experimentally measured large absorption enhancement in nanoparticle-integrated ultra-thin silicon wafer further confirms the predication. Combing the benefit of thinner wafer induced higher Voc, high-efficiency ultra-thin plasmonic wafer cells using a tiny amount of Si material have been demonstrated providing a viable solution for dramatically increased cost-effectiveness for Si wafer solar cells.

References

Goetzberger, A., Hebling, C. & Schock, H. Photovoltaic materials, history, status and outlook. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 40, 1–46 (2003).

International Technology Roadmap for Photovoltaic (ITRPV) Results 2012. (2013) (Date of access: 06/2013).

Werner, J., Kolodinski, S., Rau, U., Arch, J. & Bauser, E. Silicon solar cell of 16.8 μm thickness and 14.7% efficiency. Appl. Phys. Lett. 62, 2998 (1993).

Wang, A., Zhao, J., Wenham, S. & Green, M. 21.5% efficient thin silicon solar cell. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 4, 55–58 (1996).

Munzer, K., Holdermann, K., Schlosser, R. & Sterk, S. Thin monocrystalline silicon solar cells. IEEE Trans. Electron Dev. 46, 2055 (1999).

Willeke, G. Thin crystalline silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 72, 191 (2002).

Brendel, R. & Queisser, H. On the thickness dependence of open circuit voltages of p-n junction solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 29, 397 (1993).

Tiedle, T., Yablonovitch, E., Cody, G. & Brooks, B. Limiting efficiency of silicon solar cells. IEEE Trans. Electron Dev. ED-31, 711 (1984).

Atwater, H. & Polman, A. Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat. Mater. 9, 205–213 (2010).

Gu, M. et al. Nanoplasmonics: a frontier of photovoltaic solar cells. Nanophotonics 1, 235–248 (2012).

Derkacs, D., Lim, S., Matheu, P., Mar, W. & Yu, E. Improved performance of amorphous silicon solar cells via scattering from surface plasmon polaritons in nearby metallic nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 093103 (2006).

Eminian, C., Haug, F., Cubero, O., Niquille, X. & Ballif, C. Photocurrent enhancement in thin film amorphous silicon solar cells with silver nanoparticles. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 19, 260–265 (2011).

Chen, X. et al. Broadband enhancement in thin-film amorphous silicon solar cells enabled by nucleated silver nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 12, 2187–2192 (2012).

Lare, M., Lenzmann, F., Verschuuren, M. & Polman, A. Mode coupling by plasmonic surface scatterers in thin-film silicon solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 221110 (2012).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Effective light trapping in polycrystalline silicon thin-film solar cells by means of rear localized surface plasmons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 261109 (2010).

Nakayama, K., Tanabe, K. & Atwater, H. Plasmonic nanoparticle enhanced light absorption in GaAs solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 121904 (2008).

Cai, B., Jia, B., Shi, Z. & Gu, M. Near-field light concentration of ultra-small metallic nanoparticles for absorption enhancement in a-Si solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 093107 (2013).

Jia, B. et al. Concept to devices: from plasmonic light trapping to up-scaled plasmonic solar module. Photon. Res. 1, 22 (2013).

Fahim, N., Jia, B., Shi, Z. & Gu, M. Simultaneous broadband light trapping and fill factor enhancement in crystalline silicon solar cells induced by Ag nanoparticles and nanoshells. Opt. Express 20, A694–A705 (2012).

Beck, F., Mokkapati, S. & Catchpole, K. Plasmonic light-trapping for Si solar cells using self-assembled Ag nanoparticles. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 18, 500–504 (2010).

Yang, Y. et al. Enhanced light trapping for high efficiency crystalline solar cells by the application of rear surface plasmons. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 101, 217–226 (2012).

Temple, T., Mahanama, G., Reehal, H. & Bagnall, D. Influence of localized surface plasmon excitation in silver nanoparticles on the performance of silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 93, 1978–1985 (2009).

Xu, R. et al. Influence of the light trapping induced by surface plasmons and antireflection film in crystalline silicon solar cells. Opt. Express 20, 5061–5068 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Low cost and high performance Al nanoparticles for broadband light trapping in Si wafer solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 151101 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Improved multicrystalline Si solar cells by light trapping from Al nanoparticle enhanced antireflection coating. Opt. Mat. Express 3, 489–495 (2013).

Chen, X., Jia, B., Zhang, Y. & Gu, M. Exceeding the limit of plasmonic light trapping in textured screen-printed solar cells using Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like graphene sheets. Light Sci. Appl. 2, e92; 10.1038/lsa.2013.48 (2013).

Fahim, N. et al. Enhanced photocurrent in crystalline silicon solar cells by hybrid plasmonic antireflection coatings. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 261102 (2012).

Hägglund, C., Zäch, M., Petersson, G. & Kasemo, B. Electromagnetic coupling of light into a silicon solar cell by nanodisk plasmons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 053110 (2008).

Palik, E. D. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids (Academic, New York, 1985).

Green, M. Self-consistent optical parameters of intrinsic silicon at 300 K including temperature coefficient. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 92, 1305–1310 (2008).

Spinelli, P. et al. Optical impedance matching using coupled plasmonic nanoparticle arrays. Nano Lett. 11, 1760–1765 (2011).

Rahmani, M. et al. Beyond the hybridization effects in plasmonic nanoclusters: diffraction-induced enhanced absorption and scattering. Small 10, 576–583 (2014).

Yu, Z., Raman, A. & Fan, S. Nanophotonic light-trapping theory for solar cells. Appl. Phys. A 105, 329–339 (2011).

Yu, Z., Raman, A. & Fan, S. Fundamental limit of nanophotonic light trapping in solar cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17491–17496 (2010).

Clugston, D. A. & Basore, P. A. PC1D version 5: 32-bit solar cell modelling on personal computers. Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, 1997., Conference Record of the Twenty-Sixth IEEE, Anaheim, CA, 207–210 (09/1997-10/1997).

Black, L. E. & Mclntosh, K. R. Surface passivation of c-Si by atmospheric pressure chemical vapor deposition of Al2O3 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 202107 (2012).

Kerr, M. J. & Cuevas, A. Very low bulk and surface recombination in oxidized silicon wafers. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 17, 35–38 (2002).

Kerr, M. J. & Cuevas, A. Recombination at the interface between silicon and stoichiometric plasma silicon nitride. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 17, 166–172 (2002).

Chowdhury, Z. R., Cho, K. & Kherani, N. P. High-quality surface passivation of silicon using native oxide and silicon nitride layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 021601 (2012).

Schultz, O., Mette, A., Hermle, M. & Glunz, S. W. Thermal oxidation for crystalline silicon solar cells exceeding 19% efficiency applying industrially feasible process technology. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 16, 317–324 (2008).

Wang, S. et al. Large-area free-standing ultrathin single-crystal silicon as processable materials. Nano Lett. 13, 4393–4398 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Victorian Government under the Victoria Science Agenda (VSA) scheme. Yinan Zhang would like to thank Suntech Power Holdings Co., Ltd. for providing financial support. Min Gu also acknowledges the support from the Science and Industry Endowment Fund. Shanhui Fan acknowledges the support from the U. S. Department of Energy Grant No. DE-FG07ER46426. The authors are grateful to Zi Ouyang for discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., N.S., B.J. and M.G. designed the concept, performed the simulation and the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.F. contributed to the data analysis and the manuscript writing.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Stokes, N., Jia, B. et al. Towards ultra-thin plasmonic silicon wafer solar cells with minimized efficiency loss. Sci Rep 4, 4939 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04939

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04939

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.