Abstract

Here, W(NxS1−x)2 nanoflowers were fabricated by simple sintering process. Photocatalytic activity results indicated our fabricated N-doped WS2 nanoflowers shown outstanding photoactivity of degradating of rhodamine B with visible light. Which is attributed to the high separation efficiency of photoinduced electron–hole pairs, the broadening of the valence band (VB), and the narrowing of energy band gap. Meanwhile, our work provided a novel method to induce surface sulfur vacancies in crystals by introduing impurities atoms for enhancing their photodegradation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past decades, there has been a great interest in developing semiconductor-based photocatalysts due to its high catalytic efficiency and good stability for water splitting and removal of hazardous organic compounds in industrial wastewater using solar energy1,2,3,4,5,6. TiO2, a typical traditional photocatalyst, has many merits, including its low cost, high efficiency and excellent stability7. However, it can’t absorb visible light and suffers from fast recombination rate of the photogenerated charge carriers8. In order to overcome these drawbacks, numerous investigations have been devoted to give new types of photocatalysts, where two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials with exotic electronic properties and high specific surface areas are considered to be the good candidates9,10, as well as, they have attracted tremendous attention in heterogeneous catalysis11,12,13, sensors14, energy storage15,16 and electronics17,18,19.

Recently, transition metal sulfide has attracted intensive attention for their graphene-like structure. Tungsten disulfide (WS2), belonging to layered transition-metal dichalcogenides family, exhibits extraordinary electrical19 and photonic properties20,21. WS2 possesses hexagonal crystal structure with space group P63/mmc and each WS2 monolayer contains an individual layer of W atoms with 6-fold coordination symmetry, which are then hexagonally packed between two trigonal atomic layers of S atoms22. Generally, bulk WS2 has an indirect band gap of 1.35 eV, and when it is thinned to a single layer it becomes direct band gap semiconductor with a gap of 2.05 eV23,24. Hence, fewer layers WS2 nanosheets are the promising candidates for photocatalyst because of the number of active sites increases with the specific surface area at the nanoscale and the sites promote interfacial charge transfer for photo-induced electron-hole pairs25,26.

Nitrogen (N) doping is widely used in traditional semiconductor industry for effectively controlling their electronic properties. Recently, results indicated that the N doped graphene had the improved photocatalytic performance of photocatalysts than the bare graphene. Sacco et al. found that the N-doped TiO2 showed a higher photocatalytic activity for photodegradation of phenol under visible light irradiation than the TiO2 and titanium dioxide (P25)8. Meng et al. also reported that the photocatalytic the MO (methyl orange) evolution of N-La2Ti2O7 could be effectively improved by N doping27. In addition, many other researchers also demonstrated that various photocatalysts such as N-ZrO228, N-(BiO)2CO329, N-BiVO430 and N-ZnO31 showed a higher photocatalytic performance compared to their pure phase.

In this paper, we reported a different approach for the synthesis of WS2 nanoflowers with in-suit nitrogen-doping by a simple sintering process. Results indicated that the fabricated N-doped WS2 nanoflowers showed a BET area as high as 58.87 m2/g, which was 19.3 times than that of bare WS2 nanosheets (BET area 3.05 m2/g)32. In addition, we reported the excellent visible light-induced degradation of rhodamine B by N-doped WS2 nanoflowers. Results indicated that 20 mg of our photocatalysis could completely degrade 50 ml of 20 mg L−1 RhB in 70 minutes with excellent recycling and structural stability.

Experiment

All of the starting reagents used in this research are of analytical purity and used without further purification.

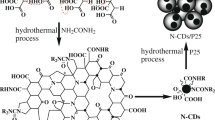

W(NxS1−x)2 nanoflowers were synthesized by an operability sintering method (as shown in Fig. 1). 0.5 g tungsten hexachloride (WCl6) was mixed with different amount of thiourea (CH4N2S) (0.5 g, 1 g, 2 g) by dropwise addition of alcohol. Then the dark-grey precursor powders were formed after drying and transferred into a quartz boat and heated in a tube furnace for 2 h under 0.1 L min−1 argon flow at 550 °C.

In order to further compare, bulk N-dope WS2 was prepared with the 0.5 g tungsten WCl6 mixed with 2 g CH4N2S by keeping above experiment condition in a tube furnace for 2 h under 0.1 L min−1 argon flow at 850 °C.

α-Fe2O3@ N-doped MoS2 heterostructures were synthesized by the hydrothermal method, where 90 mg N-doped MoS2 were dissolved into 32 ml deionized water. Then 0.202 g Fe(NO3)3·9H2O and 0.3 g CO(NH2)2 were dissolved into above solution under magnetic stirring. After that, 0.006 g sodium dodecyl benzenesulphonate (SDBS) were added into the above solution and continuous stirred in a water bath of 60 °C for 30 min. Finally, the solution was transferred to a 40 ml reactor and maintained at 90 °C for 12 h before being cooled down in air.

The crystal structure of the samples were measured by X-ray diffractometry (XRD) in a Philips/X’ Pert PRO diffractometer with Cu Ka radiation. Scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4800) and high resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM, TecnaiTM G2 F30, FEI, USA) were used to observe the morphology and structure of the products. In addition, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, VG Scientific ESCALAB-210) was employed to study the chemical nature of N, W and S with Al Ka X-ray, where the N concentration for the obtained three samples were measured to be 0.3 at.%, 0.6 at.% and 1.2 at.%. For convenience, the three samples were named as S 0.3, S 0.6, S 1.2. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area and pore width were measured by using a Micrometrics ASAP 2020 V403 measurement. Meanwhile, Raman spectra were measured in a room temperature using a Jobin-Yvon HR 800 spectrometer.

The photocatalytic activity of the samples were measured by degradation of RhB with a 175 W halogen lamp. 50 ml RhB (20 mg l−1) were placed in a glass, meanwhile, 20 mg photocatalysts were added under constantly stirring. Photocalytic activity of the sample was evaluated under visible light irradiation. At certain time intervals, 4 ml solution was taken out and using a centrifugal machine to remove photocatalytic. Then the filtrates were analyzed by recording variations of the absorption band maximum (553 nm) in the UV-vis spectra of RhB by using a UV-vis spectrophotometer. In addition, the recyclability of the sample was also investigated.

Results and Discussion

Characterization

The obtained product of S1.2 and the Used sample (N-doped WS2 nanoflowers were used by the photocatalytic activity testing) were first measured by XRD and the results are illustrated in Fig. 1a. As can be seen that the five distinct peaks correspond to (002), (012), (104), (110), and (202) diffraction peacks of hexagonal WS2 (JCPDF 84–1399). For the Used sample, all the diffraction peaks exist and no other new phase appear, indicating that our sample has a stable structure in the photocatalytic process, which is further proved by Raman spectrum (Fig. 2b). The Raman spectrum shows typical features of layered WS2 where the  and A1g modes are, located around 350 and 417 cm−133,34. For the Used sample, the two distinct peaks were similar to the primitive product, providing more stable evidence for the property. To investigate the morphology of samples, the SEM measurement was considered and the result for sample S1.2 are presented in Fig. 2c and d. It can be seen from Fig. 2c and d that the sample show the flower-like structure and each of the component shows nanosheet feature. It can be seen that the morphology of our sample didn’t change obviously after photocatalytic, which also reveal the obtained product has a stable structure. Besides, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis was carried out to verify the element-composition of the sample. As shown in the inset of Fig. 2c, EDS result clearly shows the presence of elements W, S and N in our fabricated sample.

and A1g modes are, located around 350 and 417 cm−133,34. For the Used sample, the two distinct peaks were similar to the primitive product, providing more stable evidence for the property. To investigate the morphology of samples, the SEM measurement was considered and the result for sample S1.2 are presented in Fig. 2c and d. It can be seen from Fig. 2c and d that the sample show the flower-like structure and each of the component shows nanosheet feature. It can be seen that the morphology of our sample didn’t change obviously after photocatalytic, which also reveal the obtained product has a stable structure. Besides, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis was carried out to verify the element-composition of the sample. As shown in the inset of Fig. 2c, EDS result clearly shows the presence of elements W, S and N in our fabricated sample.

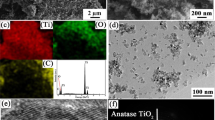

To further verify the morphology of the as prepared sample, the TEM measurement was employed. As illustrated in Fig. 3a and c, the results also indicate our sample (S 1.2) shows the nanoflower-structure. From the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) of N-doped WS2 nanoflowers (S1.2, shown in Fig. 3b), it can be intuitively seen that the sample reveals prefect lattice features, meanwhile, the interlayer spacing of ≈1.9 nm agrees well with the (012) planes of WS2. The inset of Fig. 3b shows the outstanding layered structure of the N-doped WS2 nanoflowes. Figure 3c shows the HAADF-STEM (High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy) image of S1.2. In addition, N, W and S element mapping are shown in Fig. 3d to f respectively, where the result indicates N element is evenly distributed in the sample.

To study the composition and chemical nature of the as-prepared N-doped WS2 nanoflowers, XPS spectrum was exployed. As shown in Fig. 4a, it can be clearly seen that the full range XPS spectrum of the N-doped WS2 nanoflowers (S1.2) only contains N, S, and W elements, indicating there is no impurity elements in the sample. The high-resolution XPS spectrum of W 4f7/2 and W 4f5/2 are located at 32.7 and 34.8 eV, as shown in Fig. 4b. The XPS spectrum of W 4 f for S 1.2 can be deconvoluted into four peaks, which are attributed to the following functional groups: W-N bonds (33.2 eV and 35.3 eV) and W-S bonds (32.6 eV and 34.7 eV), indicating parts of S sites were replaced by N in WS2. Meanwhile, Fig. 4c shows the S 2p XPS spectrum, which can be separated into two peaks at 162.4 eV and 163.5 eV, corresponding with S-W bonds of S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2. In order to further prove that the parts of S sites are replaced by N in WS2, the XPS spectrum of N 1s is fitted. As shown in Fig. 4d, two well-defined peaks can be distinguished, which indicated the N 1s binding energies were 397.4 eV and 399.5 eV, respectively. Generally, the peaks at 400 eV can be assigned to N that is surface bond with N or O, which is in agreement with other previous results35. Another peaks at 397.2 eV can be assigned to N-W band36, further indicating the parts of S sites are replaced by N on WS2. In addition, the nitrogen adsorption-desorption curves were performed to further study the specific surface area of the samples and the result of the representive sample S 1.2 are presented in Fig. 4e and f, revealing the sample has a larger BET area of representive sample S 1.2 (58.87 m2/g), which is lager than report results of Wu et al. (1.6 m2/g)37 and Mackie et al. (3.05 m2/g)32. The much enhanced surface area is beneficial for facilitating catalytic reaction in terms of the increase in the number of active sites38.

Evaluation of photocatalytic Reaction

The photocatalytic performances of the as-prepared samples were evaluated by degrading of RhB aqueous solution at room temperature under visible light irradiation, as shown in Fig. 5. As shown in Fig. 5a, the sample S 1.2 and its bulk were used in degrading the RhB under visible light irradiation, which can be clearly seen that the degrading rate of RhB of S 1.2 is larger than its bulk in a visible light irradiation although the absorbed rate of RhB of sample S 1.2 shows the similar value with its bulk in a dark condition (Table 1) (Supporting Information S1), which may be corresponding with its bandgap (S 1.2 1.68 eV, bulk 1.82 eV) and BET area (S 1.2 58.87 m2/g, bulk 24.64 m2/g), as shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information). Meanwhile, plots of the absorbance versus wavelength for degradation of RhB for N-doped WS2 nanoflowers at various irradiation times is shown in Fig. 5b. It can be seen that the intensity of the absorption peaks continuously decreases without any changes in their position during the degradation reactions, and its intensity sharp decreases in 10 minutes and then disappear gradually in 70 minutes. For the purpose of practical use, the stability of S 1.2 was also investigated by the degradation of RhB under visible-light irradiation (Fig. 5c). It can be clearly seen that the as-prepared N-WS2 nanoflowers does not exhibit obvious loss in photocatalytic activity even after using for 4 cycles, revealing its excellent recycling and structural stability (previous XRD and Raman results). In addition, to study the influence of the N concentration on the photocatalytic activity of N-doped WS2 nanofloweres, a series of photocatalytic experiments were carried out for the N-doped WS2 nanoflowes with different N concentration. As can be clearly seen from Fig. 5d that the degrading rate of RhB with the photocatalysts followed the order of S 1.2 (1.2 at% N) > S 0.6 (0.6 at% N) > S 0.3 (0.3 at% N), indicating the degradation rate is gradually increases with the increasing of the N concentration.

(a) Visible-light-promoted photocatalytic degradation of RhB carried out by S 1.2 and the bulk. (b) UV-vis spectra of RhB solution degraded by S 1.2 after 70 minutes (RhB solution 20 mg l−1). (c) Reusability experiment for degradation of RhB by N-doped WS2 nanoflowers under visible light irradiation. (d) Photodegradation of RhB by S 0.3, S 0.6 and S 1.2 under visible light irradiation.

Mechanism of Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity and Efficiency

The separation efficiency of photogenerated electron and hole pairs plays an important role in the enhancement of photocatalytic activity, which can be confirmed by the photocurrent measurement39,40. Actually, larger magnitude of photocurrent suggests higher charge collection efficiency of the electrode surface, indicating higher separation efficiency of electron-hole pairs. Figure 6a shows the photocurrent results of sample S 1.2. Comparing with recently reported photocatalysts, such as Jia et al. (1.7*10−5 A/m−2)41, Wen et al. (1.75*10−3 A/m−2)42, Zhi et al. (3.2*10−1 A/m−2)43, Wei et al. (2.4*10−5 A/m−2)44 and Gui et al. (1.75*10−1 A/m−2), our sample possesses a highest photocurrent of (7.04*10−1 A/m−2), indicating the higher separation efficiency of electron-hole pairs. In order to verify which parameter of hydroxyl radical (∙OH), superoxide radical  , and holes (h+) influences the photocatalytic degradation process, the degradation of RhB over S 1.2 with various scavengers were explored. As shown in Fig. 6b, for our N-doped WS2 system, the photocatalytic performance decreased greatly by addition of TBA or t-BuOH (Supporting Information S4), but changed very slightly by addition of others scavengers, suggesting that the hydroxyl radical is the domination oxidative species of N-doped WS2 and others only play an assistant roles.

, and holes (h+) influences the photocatalytic degradation process, the degradation of RhB over S 1.2 with various scavengers were explored. As shown in Fig. 6b, for our N-doped WS2 system, the photocatalytic performance decreased greatly by addition of TBA or t-BuOH (Supporting Information S4), but changed very slightly by addition of others scavengers, suggesting that the hydroxyl radical is the domination oxidative species of N-doped WS2 and others only play an assistant roles.

The band-gap energy of all the samples are estimated from the plot of (ahv)n versus hv by extrapolating the straight line to the X axis intercept, as shown in Fig. 7a–c. The band-gap energies of S 0.3, S 0.6 and S 1.2 are found to be 2.0, 1.75 and 1.68 eV, respectively. Results indicate the band-gap energy is gradually decreased with the increasing of the N concentration45. In addition, to further study the influence of the N concentration on the band gap, the density of states (DOS) of the valence band of N-doped WS2 photocatalysts were measured by the valance band XPS. As shown in Fig. 7d–f, it can be clearly seen that the edge of the valance band energy with the photocatalysts followed the order of S 0.3 > S 0.6 > S 1.2, indicating the valance band maximum rise with low density of states46. The band gap shift is attributed to lattice defects such as those arising from interstitial nitrogen47.

Based on the above results, a schematic diagram for the density of states of pure WS2 and N-doped WS2 nanoflowers has been proposed shown in Fig. 8 to give the mechanism of enhanced Photocaptalytic activity and efficiency in N doped WS2 nanoflowers. The forbidden gap of pure WS2 (2.49 eV) was reported by Hong et al.48, which can only absorb light wavelength less than 498 nm. In recent reports, numerous investigations have been enhanced photocatalysis efficiency by introduced surface oxygen vacancies in several semiconductors, such as, BiPO449, CeO250 and Bi-component Cu2O-CuCl51, which could be demonstrated to be conductive to band gap narrowing and photoactivity. Compared to the surface oxygen vacancies, the introduction of surface sulfur vacancies by doping N in our research narrows band gap and many shallow surface sulfur vacancies appear at the valance band (VB), as well as, N doping could introduce an impurity band. Furthermore, the introduction of surface sulfur vacancies can expand the VB width, which contributes to increasing the separation efficiency of photoinduced electron-hole pairs, leading to enhancement of photocatalytic activity. Moreover, N doping can extend the visible light absorption edge and the electrons are excited from the N impurity level to the conduction band, guaranteeing higher activity in degrading RhB52. Therefore, our sample possesses a high photocatalytic efficiency.

In addition, although as-prepared N-doped WS2 nanoflowers show obvious photocatalysis, it is not so easy to recycle. Catalysts with magnetic properties, namely magnetic catalysts could overcome this problem53. Therefore, it is gratifying to find a strategy for fabricating magnetic photocatalysts. Recently, magnetically separable semiconductor materials have attracted increasing attention because of their efficient recycle in water treatment, such as, Ni-Au-Zn54, NiO nanosheets55, Ag@AgCl56, r-Fe2O3@TiO257and etc. Here, α-Fe2O3@N-doped WS2 heterostructure with strong magnetic property was prepared and employed to magnetically separate our catalysts from the solution of RhB. The SEM and TEM results of α-Fe2O3@N-doped WS2 heterostructure is shown in Figure S3 (Supporting Information). As shown in Fig. 9, the degradation rate of RhB is almost 50% in 70 minutes, and it can be magnetically separation in 30s (shown in the upper right of Fig. 9). These results indicate that α-Fe2O3@N-doped WS2 heterostructure can not only serve as efficient photocatalysts but also easy separate from organic pollutants.

Conclusions

In summary, we fabricated a series of W(NxS1−x)2 nanoflowers via regulation of the mass ratio between tungsten pentachloride and thiourea in a mixed solvent system, as well as, fabricated the α-Fe2O3@N-doped WS2 heterostructure. Under visible light irradiation, N doping can significantly increase the photocatalytic performance of WS2 with the best efficiency obtained for 1.2 at% nitrogen doping. The expanded the utilization of visible light and the enhanced photoccatalytic activity both are resulted from the production of the surface sulfur vacancies by N doping. Meanwhile, we also demonstrated that the α-Fe2O3@N-doped WS2 heterostructure can be easily separated from the organic pollutants, which improves the actual utilization rate of our sample.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, P. et al. Efficient visible light-induced degradation of rhodamine B by W(NxS1−x)2 nanoflowers. Sci. Rep. 7, 40784; doi: 10.1038/srep40784 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Xiang, Q. & Yu, J. Graphene-Based Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 753–759 (2013).

Xiang, Q., Yu, J. & Jaroniec, M. Graphene-based semiconductor photocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 782–796 (2012).

Kubacka, A., Fernandez-Garcia, M. & Colon, G. Advanced nanoarchitectures for solar photocatalytic applications. Chem. Rev. 112, 1555–1614 (2012).

Chen, X., Shen, S., Guo, L. & Mao, S. S. Semiconductor-based Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Chem. Rev. 110, 6503–6570 (2010).

Asahi, R., Morikawa, T., Ohwaki, T., Aoki, K. & Taga, Y. Visible-light photocatalysis in nitrogen-doped titanium oxides. Science 293, 269–271 (2001).

Zou, Z., Ye, J., Sayama, K. & Arakawa, H. Direct splitting of water under visible light irradiation with an oxide semiconductor photocatalyst. Nature 414, 625–627 (2001).

Zhang, Y. et al. C-doped hollow TiO2 spheres: in situ synthesis, controlled shell thickness, and superior visible-light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B- Environ. 165, 715–722 (2015).

Sacco, O., Vaiano, V., Han, C., Sannino, D. & Dionysiou, D. D. Photocatalytic removal of atrazine using N-doped TiO2 supported on phosphors. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 164, 462–474 (2015).

Hu, K. H., Hu, X. G., Xu, Y. F. & Pan, X. Z. The effect of morphology and size on the photocatalytic properties of MoS2. Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms and Catalysis (2010).

He, Y. et al. Efficient degradation of RhB over GdVO4/g-C3N4 composites under visible-light irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 215–216, 721–730 (2013).

Chhowalla, M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5 (2013).

Liang, S. et al. Molecular recognitive photocatalytic degradation of various cationic pollutants by the selective adsorption on visible light-driven SnNb2O6 nanosheet photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 125, 103–110 (2012).

Liang, S. et al. Monolayer HNb3O8 for selective photocatalytic oxidation of benzylic alcohols with visible light response. Angew. Chem. 53, 2951–2955 (2014).

Li, H., Wu, J., Yin, Z. & Zhang, H. Preparation and applications of mechanically exfoliated single-layer and multilayer MoS2 and WSe2 nanosheets. Accounts Chem. Res. 47, 1067–1075 (2014).

Sun, Y., Gao, S. & Xie, Y. Atomically-thick two-dimensional crystals: electronic structure regulation and energy device construction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 530–546 (2014).

Peng, X., Peng, L., Wu, C. & Xie, Y. Two dimensional nanomaterials for flexible supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 3303–3323 (2014).

Osada, M. & Sasaki, T. Exfoliated oxide nanosheets: new solution to nanoelectronics. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 2503 (2009).

Osada, M. & Sasaki, T. Two-dimensional dielectric nanosheets: novel nanoelectronics from nanocrystal building blocks. Adv. Mater. 24, 210–228 (2012).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Britnell, L. et al. Strong light-matter interactions in heterostructures of atomically thin films. Science 340, 1311–1314 (2013).

Gutierrez, H. R. et al. Extraordinary room-temperature photoluminescence in triangular WS2 monolayers. Nano lett. 13, 3447–3454 (2013).

Rout, C. S. et al. Superior field emission properties of layered WS2-RGO nanocomposites. Sci. Rep-UK 3, 3282 (2013).

Braga, D., Gutierrez Lezama, I., Berger, H. & Morpurgo, A. F. Quantitative determination of the band gap of WS2 with ambipolar ionic liquid-gated transistors. Nano lett. 12, 5218–5223 (2012).

Georgiou, T. et al. Vertical field-effect transistor based on graphene-WS2 heterostructures for flexible and transparent electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 100–103 (2013).

Vattikuti, S. V. P., Byon, C. & Chitturi, V. Selective hydrothermally synthesis of hexagonal WS2 platelets and their photocatalytic performance under visible light irradiation. Superlattice Microst. 94, 39–50 (2016).

Peng, B., Ang, P. K. & Loh, K. P. Two-dimensional dichalcogenides for light-harvesting applications. Nano Today 10, 128–137 (2015).

Meng, F. et al. Visible light photocatalytic activity of nitrogen-doped La2Ti2O7 nanosheets originating from band gap narrowing. Nano Res. 5, 213–221 (2012).

Sudrajat, H., Babel, S., Sakai, H. & Takizawa, S. Rapid enhanced photocatalytic degradation of dyes using novel N-doped ZrO2 . J. Environ. Manage. 165, 224–234 (2016).

Dong, F., Liu, H., Ho, W.-K., Fu, M. & Wu, Z. (NH4)2CO3 mediated hydrothermal synthesis of N-doped (BiO)2CO3 hollow nanoplates microspheres as high-performance and durable visible light photocatalyst for air cleaning. Chem. Eng. J. 214, 198–207 (2013).

Wang, M., Liu, Q., Che, Y., Zhang, L. & Zhang, D. Characterization and photocatalytic properties of N-doped BiVO4 synthesized via a sol–gel method. J. Alloy. Compd. 548, 70–76 (2013).

Zong, X. et al. Activation of Photocatalytic Water Oxidation on N-Doped ZnO Bundle-like Nanoparticles under Visible Light. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 4937–4942 (2013).

Mackie, E. B., Galvan, D. H. & Migone, A. D. Methane adsorption on planar WS2 and on WS2-fullerene and -nanotube containing samples. Adsorption 6, 169–174 (2000).

Cheng, L. et al. Ultrathin WS2 nanoflakes as a high-performance electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. 53, 7860–7863 (2014).

Gao, Y. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform monolayer WS2 on reusable Au foils. Nat. Commun. 6, 8569 (2015).

Ghicov, A. et al. Ion implantation and annealing for an efficient N-doping of TiO2 nanotubes. Nano lett. 6, 1080–1082 (2006).

Nossa, A. & Cavaleiro, A. Chemical and physical characterization of C(N)-doped W–S sputtered films. J. Mater. Res. 19, 2356–2365 (2011).

Wu, Z. et al. WS2 nanosheets as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 125, 59–66 (2012).

Benck, J. D., Hellstern, T. R., Kibsgaard, J., Chakthranont, P. & Jaramillo, T. F. Catalyzing the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) with molybdenum sulfide nanomaterials. ACS Catal. 4, 3957–3971 (2014).

Ng, Y. H., Lightcap, I. V., Goodwin, K., Matsumura, M. & Kamat, P. V. To what extent do graphene scaffolds improve the photovoltaic and photocatalytic response of TiO2 nanostructured films? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 2222–2227 (2010).

Han, Z., Chen, G., Li, C., Yu, Y. & Zhou, Y. Preparation of 1D cubic Cd0.8 Zn0.2S solid-solution nanowires using levelling effect of TGA and improved photocatalytic H2-production activity. J Mater. Chem. A 3, 1696–1702 (2015).

Qin, J. et al. Improving the photocatalytic hydrogen production of Ag/g-C3N4 nanocomposites by dye-sensitization under visible light irradiation. Nanoscale 8, 2249–2259 (2016).

Jiang, W. et al. Integration of Multiple Plasmonic and Co-Catalyst Nanostructures on TiO2 Nanosheets for Visible-Near-Infrared Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Small 12, 1640–1648 (2016).

Yan, Z., Sun, Z., Liu, X., Jia, H. & Du, P. Cadmium sulfide/graphitic carbon nitride heterostructure nanowire loading with a nickel hydroxide cocatalyst for highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production in water under visible light. Nanoscale 8, 4748–4756 (2016).

Chen, W., Liu, T. Y., Huang, T., Liu, X. H. & Yang, X. J. Novel mesoporous P-doped graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets coupled with ZnIn2S4 nanosheets as efficient visible light driven heterostructures with remarkably enhanced photo-reduction activity. Nanoscale 8 (2016).

Sun, C. et al. N-doped WS2nanosheets: a high-performance electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 11234–11238 (2016).

Lv, Y., Yao, W., Zong, R. & Zhu, Y. Fabrication of Wide-Range-Visible Photocatalyst Bi2WO6−x nanoplates via Surface Oxygen Vacancies. Sci. Rep-UK. 6, 19347 (2016).

Xie, J. et al. Mussel-Directed Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Anatase TiO2 . Angew. Chem. 55, 3031–3035 (2016).

Shi, H. L., Pan, H., Zhang, Y. W. & Yakobson, B. I. Quasiparticle band structures and optical properties of strained monolayer MoS2 and WS2 . Phys. Rev. B 87, 155304 (2013).

Wei, Z. et al. Controlled synthesis of a highly dispersed BiPO4 photocatalyst with surface oxygen vacancies. Nanoscale 7, 13943–13950 (2015).

Younis, A., Chu, D., Kaneti, Y. V. & Li, S. Tuning the surface oxygen concentration of {111} surrounded ceria nanocrystals for enhanced photocatalytic activities. Nanoscale 8, 378–387 (2016).

Yang, R. et al. Bi-component Cu2O–CuCl composites with tunable oxygen vacancies and enhanced photocatalytic properties. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 170–171, 225–232 (2015).

Liu, Y., Li, Y., Li, W., Han, S. & Liu, C. Photoelectrochemical properties and photocatalytic activity of nitrogen-doped nanoporous WO3 photoelectrodes under visible light. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 5038–5045 (2012).

Dong, Z., Le, X., Liu, Y., Dong, C. & Ma, J. Metal organic framework derived magnetic porous carbon composite supported gold and palladium nanoparticles as highly efficient and recyclable catalysts for reduction of 4-nitrophenol and hydrodechlorination of 4-chlorophenol. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 18775–18785 (2014).

Zeng, D. et al. Synthesis of Ni-Au-ZnO ternary magnetic hybrid nanocrystals with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Nanoscale 7, 11371–11378 (2015).

Dong, Q. et al. Single-crystalline porous NiO nanosheets prepared from β-Ni(OH)2 nanosheets: Magnetic property and photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 147, 741–747 (2014).

Gamage McEvoy, J. & Zhang, Z. Synthesis and characterization of magnetically separable Ag/AgCl–magnetic activated carbon composites for visible light induced photocatalytic detoxification and disinfection. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 160–161, 267–278 (2014).

Mou, F. et al. Facile preparation of magnetic gamma-Fe2O3/TiO2 Janus hollow bowls with efficient visible-light photocatalytic activities by asymmetric shrinkage. Nanoscale 4, 4650–4657 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Fundation of China (Grant No. 11474137, 51301081 and 11274146), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. lzujbky-2014-27 and No. lzujbky-2016-130).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Peitao Liu and Daqiang gao wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 and 9. Jingyan Zhang and Weichun Ye reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, P., Zhang, J., Gao, D. et al. Efficient visible light-induced degradation of rhodamine B by W(NxS1−x)2 nanoflowers. Sci Rep 7, 40784 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40784

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40784

This article is cited by

-

Seamless recovery and reusable photocatalytic activity of CVD grown atomically-thin WS2 films

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2024)

-

Enhanced UV Flexible Photodetectors and Photocatalysts Based on TiO2 Nanoplatforms

Topics in Catalysis (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.