Abstract

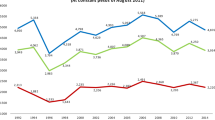

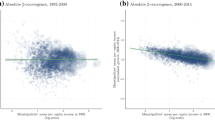

This study uses the Current Population Survey and a decomposition method proposed by Datt and Ravallion to assess the impacts of income growth and income distribution on poverty across states in the United States. It finds that between 1992 and 2011 growth of income, rather than changes in income distribution, was the major source of poverty reduction across US states. The empirical analysis also shows that there is asymmetrical impact on poverty — via both income distribution and income growth — during recessions and economic expansions: poor people are hit harder during recessions and benefit less during economic booms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The impact of the recession on the poor is technically difficult to measure because social, economic, and demographic factors are jointly involved. However, the proportion of working families below 200 percent of the poverty threshold increased sharply in 2008 and again in 2009, as many middle-class families fell into the low-income trap [Roberts et al. 2011].

For example, the 2008–2010 3-year average poverty rate of New Hampshire was 7.1 percent whereas that of Mississippi was 21.3 percent.

An analysis at the state level implies that within each state the economy is homogenous and, thus, that each state supposedly has its own steady state. This working assumption is somewhat controversial, but working with states is convenient for several reasons, including availability of good data. Moreover, states have a great deal of flexibility in terms of choosing their own policies (education, fiscal, safety, legal etc.), which would affect their long-run path of economic growth. For a discussion about states’ homogeneity, see Sedgley and Elmslie [2004].

The CPS is a nationwide survey of about 60,000 households conducted monthly for the US Bureau of Labor Statistics by the US Census Bureau. The survey is representative of the civilian non-institutionalized population of the United States with sample located in more than 2,000 counties and independent cities and coverage in every state and in the District of Columbia.

See Kraay [2006] for details about this decomposition. Our notation is slightly different from Kraay [2006]. More precisely, in our study, μ denotes the annual growth in average income instead of average income as in Kraay [2006].

The exports data utilized in this study are calculated from the Origin of Movement series (rather than Exporter Location) compiled by the Foreign Trade Division of the US Census Bureau.

All variables included in the regression analysis are measured in decimals. For instance, proportion of the population with higher education is coded 0.25, which implies that 25 percent of the population has at least a college degree.

This approach is consistent with several studies including Gittell and Tebaldi [2010] and Forbes [2000].

The authors will be happy to provide the RE results and Hausman test statistics upon request.

Because weights must be constant within states over time, we use the 1992 population as weights.

References

Anand, Sudhir, and S.M.R. Kanbur . 1993. The Kuznets Process and the Inequality-Development Relationship. Journal of Development Economics, 40 (1): 25–52.

Datt, Gaurav, and Martin Ravallion . 1992. Growth and Redistribution Components of Changes in Poverty Measures: A Decomposition with Applications to Brazil and India in the 1980s. Journal of Development Economics, 38 (2): 275–295.

Dollar, David, and Aart Kraay . 2002. Growth is Good for the Poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 7 (3): 195–225.

Duclos, Jean-Yves, and Audrey Verdier-Chouchane . 2011. Analyzing Pro-Poor Growth in Southern Africa: Lessons from Mauritius and South Africa. African Development Review, 23 (2): 121–146.

Forbes, Kristin J. 2000. A Reassessment of the Relationship between Inequality and Growth. American Economic Review, 90 (4): 869–887.

Foster, James, and Miguel Székelyi . 2008. Is Economic Growth Good for the Poor? Tracking Low Income Using General Means. International Economic Review, 49 (4): 1143–1172.

Foster, James, Joel Greer and Erik Thorbecke . 1984. A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures. Econometrica, 52 (3): 761–766.

Gittell, Ross, and Edinaldo Tebaldi . 2010. Poverty in the US Metropolitan Areas: What Are the Key Determinants and What is the Role of Local Fiscal Structure? Public Finance and Management, 10 (3): 411–442.

Glaeser, Edward, Scheinkman, Jose and Shleifer, Andrei . 1995. Economic growth in a cross section of cities. Journal of Monetary Economics, 36 (1): 117–143.

Hull, Katy . 2009. Understanding the Relationship between Economic Growth, Employment and Poverty Reduction. in Promoting Pro-Poor Growth: Employment, edited by P., Bieler. Paris, France: OECD, 69–94.

King, Miriam, Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Sarah Flood, Katie Genadek, Matthew B. Schroeder, Brandon Trampe and Rebecca Vick . 2010. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 3.0, [Machine-readable database]Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Kraay, Aart . 2006. When is Growth Pro-Poor? Evidence from a Panel of Countries. Journal of Development Economics, 80 (1): 198–227.

Negre, Mario . 2010. Concepts and Operationalization of Pro-Poor growth. WIDER Working Paper No. 2010/47.

Page, John . 2006. Strategies for Pro-Poor Growth: Pro-poor, Pro-Growth, or Both? Journal of African Economies, 15 (4): 510–542.

Ravallion, Martin . 2004. Pro-poor growth: A primer. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3242, Washington DC: World Bank.

Roberts, Brandon, Deborah Povich and Mark Mather . 2011. Great Recession Hit Hard at America’s Working Poor. The Working Poor Families Project. Available at http://www.workingpoorfamilies.org/pdfs/policybrief-winter2011.pdf, accessed 2 October 2013.

Sedgley, Norman, and Bruce Elmslie . 2004. The Geographic Concentration of Knowledge: Scale, Agglomeration and Congestion in Innovation across US Sates. International Regional Science Review, 27 (2): 111–137.

Acknowledgements

We thank anonymous referees for their thoughtful suggestions to revise and improve this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tebaldi, E., Kim, J. Is Income Growth in the United States Pro-Poor? A State-Level Analysis. Eastern Econ J 41, 251–272 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.14

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.14