Abstract

This paper presents new findings from the World Top Incomes Database and discusses some of their policy implications. In particular, the paper provides updated top income series for the United States—including new estimates through 2010, showing a strong rebound of the top 1 percent income share, following the 2008–09 sharp fall. It also presents updated income series for other developed countries (including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Japan) and new series on wealth-income ratios. In light of this extended set of country series, the paper analyzes the relative importance of market and institutional forces in explaining observed cross-country trends, and the likely impact of the Great recession on these long-term evolutions. It discusses the policy implications of the findings, both in terms of optimal tax policy and regarding the interplay between inequality and macroeconomic fragility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The share of national income accruing to upper income groups has increased sharply in recent decades, particularly in the United States. The top decile income share has risen from less than 35 percent during the 1970s to about 50 percent in recent years. This comes mostly from the very top. The top percentile income share itself has more than doubled, from less than 10 percent in the 1970s to over 20 percent in recent years. As a consequence, low and middle incomes have grown much less than what aggregate GDP growth statistics would suggest. A similar trend has also taken place in a number of other countries, especially English-speaking countries, but is much more modest in continental Europe or Japan.

This trend toward rising income concentration has raised growing concerns about both equity and efficiency. First, it is unclear whether rising US inequality can be justified by incentive considerations. There is a heated debate in the United States and elsewhere about the extent to which progressive tax policy should and could be used to reverse trends in the distribution of market income and welfare. Next, a number of observers have argued that rising top income shares might have exacerbated financial fragility, thereby imposing additional welfare costs.

In this paper, we present new findings from the World Top Incomes Database (WTID) and discuss some of their policy implications. In particular, we provide updated top income series for the United States—including new estimates for 2010, showing a sharp rebound of top 1 percent share, following the 2008–09 fall. We also present updated income series for other developed countries (including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Japan). We start by describing the basic facts emerging from our top income series, and by discussing the likely impact of the Great Recession on these long-term evolutions (Section I). We then analyze the relative importance of market and institutional forces in explaining observed cross-country trends, and the implications in terms of optimal tax policy (Section II). In Section III, we present new series on wealth-income ratios and discuss the interplay between inequality and macroeconomic fragility. Finally, we provide concluding comments (Section IV).

I. New Findings from the World Top Incomes Database

The World Top Incomes Database

The WTID is a collective project (Alvaredo and others, 2012). Beginning with the research by Piketty (2001, 2003) of the long-run distribution of top incomes in France, a succession of studies has constructed top income share time series over the long run for more than 20 countries to date. These works have generated a large volume of data, which are intended as a research resource for further analysis. This is by far the largest historical inequality data set available so far.

The WTID aims to providing convenient online access to all the existent series (see topincomes.parisschoolofeconomics.eu). This is an ongoing endeavor, and we will progressively update the base with new observations, as authors extend the series forwards and backwards. The first 22 country-studies have been included in two volumes (Atkinson and Piketty, 2007, 2010). As the map below shows, around 45 further countries are currently under study. Although the present paper chooses to focus on the findings obtained for developed countries (and particularly for the United States), the database aims to include a growing number of emerging economies.

The basic methodology used in the WTID follows the pioneering work of Kuznets (1953). That is, we use income tax data to compute top income series, and national accounts to compute aggregate income. The key advantage of these data sources is that they are available on a long run, annual basis for a large number of countries. In addition, administrative tax data are generally of higher quality than household survey data, which often suffer from severe sampling and self-reporting biases. This is particularly problematic at the top of the distribution, which is unfortunate, given the large share of aggregate income going to the top decile, and given that this is where a lot of the action has been taking place in historical evolutions. However, there are limitations with our approach, in particular, owing to the exclusion of tax-exempt income (either tax-exempt capital income or transfer income), as we shall see below.

The Rise in Top Income Shares

We start by presenting the updated version of what is probably the most spectacular result coming from the WTID, namely, the very pronounced U-shaped evolution of top income shares in the United States over the past century (Piketty and Saez, 2003), series updated to 2010). The share of total market income going to the top decile was as large as 50 percent at the eve of the 1929 Great Depression, fell sharply during the 1930s and—most importantly—during World War II, and stabilized below 35 percent between the 1940s and the 1970s. It then rose gradually since the late 1970s to the early 1980s, and is now close to 50 percent once again (see Figure 1(a)).

(a) The Top Decile Income Share in the United States, 1917–2010; (b) The Top Decile Income Share in the United States, 1917–2010 (Including Capital Gains and Excluding Capital Gains); (c) Decomposing the Top Decile US Income Share into Three Groups, 1913–2010Source: Piketty and Saez (2003), series updated to 2010. Note: Income is defined as market income including realized capital gains (excludes government transfers).

Several remarks are in order. First, the interesting new finding here is that the Great Recession of 2008–09 seems unlikely to reverse the long-run trend.Footnote 1 There was a sharp fall in the top decile share in 2008–09, but it was followed by a strong rebound in 2010. We do not have full income tax return data for 2011–12 yet, but all the preliminary tax tabulations that we have—as well as external evidence regarding corporate profits or financial bonuses—suggest that the rebound might be continuing in 2011–12. This would be consistent with the experience of the previous economic downturn. That is, top income shares fell in 2001–02, but quickly recovered and returned to the previous trend in 2003–07.

Another piece of evidence that is consistent with this interpretation is given by Figure 1(b). If we take away capital gains—unsurprisingly the most cyclical component of income—one can see that the upward trend has continued since 2007. This strongly suggests that the Great Recession will only depress top income shares temporarily and will not undo any of the marked increase in top income shares that has taken place since the 1970s. Indeed, excluding realized capital gains, the top decile share in 2010 is equal to 46.3 percent, higher than in 2007.

Next, it is worth stressing that the orders of magnitude are truly enormous. More that 15 percent of US national income was shifted from the bottom 90 percent to the top 10 percent in the United States over the past 30 years. In effect, the top 1 percent alone has absorbed almost 60 percent of aggregate US income growth between 1976 and 2007 (see Figure 1(c) and Tables 1, 2). The fact that so much action has been taking place at the level of the top 1 percent, and relatively little at the level of the next 9 percent, is probably the most staggering evolution.

These results illustrate why it is critical to use administrative tax data to study trends in income distribution. With standard surveys based on limited sample size and self-reported income (such as the Current population survey or the surveys used in the Luxembourg Income Study and standard international inequality data sets), one can measure adequately the evolution of the 90:10 threshold ratio—but one cannot measure properly incomes above the 90th percentile, and therefore one largely misses the magnitude of the trend that has been going on.Footnote 2

Next, it is striking to see that a similar—although smaller—trend has been going on in the United Kingdom and in Canada, but not in Continental Europe and Japan, where the long pattern of income inequality is much closer to an L-shaped than to a U-shaped curve (see Figure 2(a)–(c)).

It is particularly striking to compare the evolution of the top decile share in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France over the past century (see Figure 3). The United States seems to be heading back toward 50 percent of total income going to the top decile, the United Kingdom seems to be following this trend, whereas Germany and France appear to be relatively stable around or below 35 percent—not too much above the low levels observed in the 1970s–80s, and very close to those prevailing in the 1950s–60s. To us, the fact that countries with similar technological and productivity evolutions have gone through such different patterns of income inequality—especially at the very top—supports the view that institutional and policy differences may have played a key role in these transformations. Purely technological stories based solely on supply and demand of skills seem not to be sufficient to explain such diverging patterns. Changes in tax policies—which indeed vary a lot across countries—look like a more promising candidate. We return to this below when we discuss optimal tax policies.

Another interesting lesson emerging from our historical perspective is the comparison between the Great Depression and the Great Recession. Downturns do not seem to have long-run effects on inequality, even when they are very large. The reason why the Great Depression was followed by huge inequality decline is not the depression, but rather the large political shocks and policy responses—in particular the tremendous changes in institutions and tax policies—which took place in the 1930s–40s. The Great Recession is likely to have a large long-run impact only if it is followed by significant policy changes.

Changes in the Composition of Top Incomes

Finally, the composition of top incomes has changed between 1929 and 2007. In both years, the share of wage income declines and the share of capital income rises as one moves up within the top decile and the top percentile of the income distribution. However, in 2007, one needs to enter into the top 0.1 percent for capital income to dominate wage income, whereas in 1929 it was sufficient to enter the top 1 percent (see Figure 4(a)–(b)). Also note that the composition of capital income itself has changed markedly—it is today largely made up of capital gains. If one takes away capital gains, then wage income now dominates capital income at the very top (see Figure 4(c)–(d)).

Income Composition of Top Groups within the Top Decile in 1929 and 2007: Panel A: 1929; Panel B: 2007; Panel C: 1929; Panel D: 2007 (Excluding Capital Gains)Note: Wage income includes wages, bonuses, exercised stock options, and bonuses. Capital income includes rent, dividends, interest, and realized capital gains. Entrepreneurial income includes business income and income from partnerships and from S-Corporations.

One should be cautious, however, about the tax reporting rate (that is, the ratio between fiscal income, as reported in tax returns, and full economic income, as estimated by national accounts) that is today much lower for capital income than for wage income (see Table 3). If we were to correct for this downward trend in the capital income tax reporting rate, which we did not do in our published series so far, then the US level of top income shares today would probably be significantly higher than in 1929, and the composition would look closer. This would follow mechanically from the fact that capital ownership—and hence capital income—is much more strongly concentrated than labor income. In the United States, the top decile of the wealth distribution currently owns over 70 percent of aggregate wealth (according to the Survey of Consumer Finances, which understates the importance of top wealth holders; see Kennickell, 2009). In contrast, the top decile of the income distribution receives less than 50 percent of aggregate income. However, one difficulty is that we do not know whether the reporting rate is the same at all levels of capital income. In case low and middle wealth holders have a lower reporting rate (for example, owing to the fact that a larger fraction of their wealth takes the form of tax-free saving accounts), then this force might push in the opposite direction. This is an important limitation of our series that also applies to other countries (the share of tax-exempt capital income has increased pretty much everywhere during the past decades), and which should be kept in mind.Footnote 3 Another related limitation is that we did not attempt so far to include estimates for capital incomes originating from assets located in tax havens (which are typically not well recorded in resident countries, and which have grown considerably in recent decades; see Zucman, 2013). Presumably this is particularly important for very top capital incomes.

Another important limitation is that our series do not take into account tax-exempt transfer income. That is, all top income shares series presented in the WTID relate to pretax market income. Given the rise of transfers since the 1970s, this is likely to affect the trends. Ideally, one would like to extend our series in order to take into account all forms of missing incomes, that is, both missing capital income (this would tend to raise top income shares) and missing transfer income (this would tend to reduce top income shares). It is unclear which effect would dominate. Also there are difficult issues related to the measurement of transfer incomes. For example, in the United States, a big part of the rise of transfers took the form of in-kind transfers, especially through Medicaid/Medicare soaring costs (with unclear value added for those exploding costs). In any case, the main—and robust—lesson from our US series is that bottom 99 percent cash market incomes have grown at a much smaller rate than aggregate per capita GDP since the 1970s, owing to the large rise in income concentration.

II. How Much Should We Tax Top Incomes?

How much should we use progressive income taxation in order to redistribute more fairly the gains from aggregate income growth? The exact answer to this question depends a great deal on the economic forces that lie behind the rise in top incomes. Assume first that the rise in inequality is, for the most part, because of skill-biased technical change and because of the increasing market price of high-skill workers in the global economy. Redistributive taxation can still play a useful role,Footnote 4 but entails potentially large incentive and efficiency costs. Using the standard optimal tax framework, and the relatively moderate labor supply elasticities found in the micro empirical literature, Diamond and Saez (2011) have argued that the revenue-maximizing top tax rate is likely to be well above 50 percent—say 60–70 percent. However, it could be that these micro labor supply elasticities underestimate longer-term responses in terms of skill acquisitions and career choices, in which case the optimal tax rate could be substantially lower.

In a recent paper, Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2013) have introduced a theoretical and empirical argument pushing in the opposite direction. They start from the observation that the rise in income inequality took place at the very top of the distribution. They then argue that in order to properly account for this, one needs to introduce a richer view of the labor market than the standard competitive model. Namely, pay may not always be equal to marginal product, and changes in bargaining power can potentially play a large role, especially regarding executive compensation. If this is correct, then the socially optimal top tax rate might be larger than what standard models suggest.

From a long-run perspective, it is indeed striking to see that the countries where top income shares have increased the most—typically the United States and the United Kingdom—are also those where top marginal income tax rates were cut the most (see Figure 5). Taking a broader cross-country perspective, and using updated WTID series in a systematic manner, we find a clear negative correlation, with an elasticity around 0.5 (see Figure 6).

Changes in Top Income Shares and Top Marginal Tax RatesNote: The figure from Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2013) depicts the change in top 1 percent income shares against the change in top income tax rate from 1960–64 to 2005–09 based on Figure 2 data for 18 OECD countries. The correlation between those changes is very strong. The figure reports the elasticity estimate of the OLS regression of Δlog(top 1 percent share) on Δlog(1-MTR) based on the depicted dots.

The central question is the following: where does this elasticity come from? Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2013) present a model of optimal labor income taxation where top incomes respond to marginal tax rates through three channels: (1) standard labor supply (including skill acquisition, entrepreneurial effort, and other productive behavioral responses), (2) tax avoidance, and (3) compensation bargaining. They show that the optimal top tax rate responds very differently to these three behavioral elasticities. The first elasticity (labor supply) is the sole real factor limiting optimal top tax rates. The optimal tax system should be designed to minimize the second elasticity (avoidance) through tax enforcement and tax neutrality across income forms. The second elasticity then becomes irrelevant. Most interestingly, the optimal top tax rate increases with the third elasticity (bargaining) as bargaining efforts are zero-sum in aggregate.

The intuition behind the bargaining elasticity is that pay may not equal marginal economic product for top income earners. In particular, executives can be overpaid if they are entrenched and use their power to influence compensation committees (Bebchuk and Fried, 2004 survey the wide corporate finance literature on this issue). More generally, pay can differ from marginal product in any model in which compensation is decided by on-the-job bargaining between an employer and an employee, as in the classic search model. In more general models, given the substantial costs involved in replacing workers who quit in most modern work environments, especially for management positions where specific human capital is important, as well as imperfect information between firm and employee, it seems reasonable to think that there would be a band of possible compensation levels. In such a context, bargaining efforts on the job can conceivably play a significant role in determining pay. Marginal tax rates affect the rewards to bargaining effort and can hence affect the level of such bargaining efforts.

Yet another reason why pay may differ from marginal product is imperfect information. In the real world, it is often very difficult to estimate individual marginal products, especially for managers working in large corporations. For tasks that are performed similarly by many workers (for example, one additional worker on a factory line), one can approximately compute the contribution to total output brought by an extra worker. But for tasks that are more or less unique, this is much more complex: one cannot run a company without a chief financial officer or a head of communication during a few years in order to see what the measurable impact on total output of the corporation is going to be. For such managerial tasks, it is very unlikely that market experimentation and competition can ever lead to full information about individual marginal products, especially in a rapidly changing corporate landscape. If marginal products are unknown, or are only known to belong to relatively large intervals, then institutions, market power, and beliefs systems can naturally play a major role for pay determination (see Rotemberg, 2002). This is particularly relevant for the recent rise of top incomes. Using matched individual tax return data with occupations and industries, Bakija, Cole, and Heim (2010) have recently shown that executives, managers, supervisors, and financial professionals account for 70 percent of the increase in the share of national income going to the top 0.1 percent of the US income distribution between 1979 and 2005.Footnote 5

It is obviously very difficult to come with a fully satisfactory decomposition of the total observed elasticity into three components. We should make clear that, in our view, both the supply-side and the bargaining theories of rising inequality and optimal taxation have some merit and capture part of what has been going on in the real world. The difficult question is to determine the exact relative importance of the two theories.Footnote 6 In addition, it is likely that other institutional factors have played a role in explaining cross-country patterns in top income shares. In particular, changing labor market institutions (including the decline of unions and the variations in public sector size over time and across countries) and industry structure (with a rising share of the finance sector, particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom) probably had a significant impact on observed evolutions. We certainly do not claim that we are able to put a precise number on each channel.

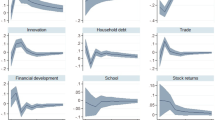

At a more modest level, we make two points. Our first point is that existing evidence seems to suggest that bargaining effects do matter. To begin with, the fact that all developed countries have had almost the same productivity growth rates over the past few decades suggests that the bargaining, zero-sum-game channel is indeed important. According to the supply-side view, we should observe markedly higher per capita growth rates in the United States and the United Kingdom as compared with Germany, Japan, Denmark, or France, which we simply do not see in the data (see Figures 7 and 8).

Top Marginal Tax Rates and Growth from 1960–64 to 2006–10: (a) Growth and Change in Top Marginal Tax Rate; (b) Growth (Adjusted for Initial 1960 GDP)Note: The figure from Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2013) depicts the average real GDP per capita annual growth rate from 1960–64 to 2006–10 against the change in top marginal tax rate. Panel A considers the raw growth rate, whereas Panel B adjusts the growth rate for initial real GDP per capita as of 1960. Formally, adjusted growth rates are obtained by regressing log(GDP) on log(1-MTR), country fixed effects, a time trend, and a time trend interacted with demeaned log(GDP). We then estimate adjusted log(GDP) by removing the estimated interaction component time × log(GDP). In both panels, the correlation between GDP growth and top tax rates is insignificant, suggesting that cuts in top tax rates do not lead to higher economic growth. Table 2 reports estimates based on the complete time series.

Top Marginal Tax Rates and Growth: 1960–64 to 1976–80 and 1976–80 to 2006–10: (a) Growth (Adjusted for Initial GDP) 1960−64 to 1976−80; (b) Growth (Adjusted for Initial GDP) 1976−80 to 2006–10Note: The figure from Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2013) depicts the average real GDP per capita annual growth rate (adjusted for initial GDP as in Figure 5, Panel B) against the change in top marginal tax rate for two subperiods: 1960–64 to 1976–80 in Panel A and 1976–80 to 2006–10 in Panel B. In both subperiods, there is no correlation between the change in top marginal tax rate and the average growth over the period. Panel B captures the period starting with the Thatcher and Reagan revolutions. Although the United States and the United Kingdom did cut top tax rates more and grew faster than France and Germany, this does not generalize to the 18 OECD countries. Some countries (such as Portugal) cut top tax rates sharply and did not grow fast. Other countries (such as Finland or Denmark) did not cut top tax rates much and yet grew as fast as the United States or the United Kingdom.

Micro evidence on top executive pay also appears to be consistent with the bargaining model. Generally speaking, the elasticity of CEO compensation with respect to lucky profits—that is, profits predicted by exogenous shocks such as mean industry performance—is larger than with respect to general profits, which can be viewed as evidence of “pay for luck” and rent extraction (as argued by Bertrand, Mullainathan, 2001). This is particularly true in countries and time periods with lower top marginal rates (such as the United States and the United Kingdom since the 1980s), which tends to suggest that top executives indeed put more bargaining efforts when the top tax rate is lower. It is also striking to note that variations in top tax rates can account for a large fraction of cross-country variations in executive pay, even after controlling for firm size and industry (which do not seem to matter nearly as much as top tax rates).Footnote 7

Our second point is that bargaining effects matter a lot for optimal tax policy, including in the plausible case where bargaining effects are moderate in size and coexist with standard supply-side effects. Our main conclusions about optimal top tax rates are summarized in Table 4. That is, assuming the total elasticity is around 0.5 (as suggested by macro cross-country evidence), then if this elasticity comes partly from standard labor supply channel (0.2) and partly from bargaining channel (0.3), then optimal top rate can be as large as 82 percent—as opposed to 57 percent if the elasticity comes entirely from standard supply-side channels.

III. Did Rising Top Incomes Exacerbate Financial Fragility?

In addition to equity and redistribution, the other major concern with rising top income shares is the potential impact on macro financial fragility. Is the fact that the two highest top decile income shares occurred in 1928 and 2007, that is, at the eve of the Great Depression and at the eve of the Great Recession, a mere coincidence?

A number of economists have argued that rising inequality and stagnant incomes for the bottom 90 percent did spur the rise of household debt—and eventually directly contributed to make the financial system more fragile and more vulnerable to shocks (see, for example, Kumhof and Ranciere, 2010; Rajan, 2010; Bertrand and Morse, 2013; see also Azzimonti, de Francisco, and Quadrini, 2012 for a similar story operating through the accumulation of government debt). Others, however, have argued on the basis of historical evidence that credit and debt booms can happen basically everywhere, and bear no systematic relationship with income inequality (see Bordo and Meissner, 2012).

On the basis of our series, our own view is the following. First, it is clear that it is partly a coincidence—a correlation rather than a causal impact. That is, a booming stock market contributes both to the rise of top incomes (in particular via capital gains, which were very large both in the 1920s and in the 2000s) and to the rise of financial fragility—but this does not imply that there is a causal relationship between rising inequality and financial fragility. Modern financial systems are very fragile and can probably crash by themselves—even without rising inequality.

However, this does not imply that rising inequality played no role at all. In our view, it is highly plausible that rising top incomes did contribute to exacerbate financial fragility. The fact that household debt rose so much and so fast in the United States during the 1990s–2000s (especially in the 2000s) and that the crash eventually occurred in the United States rather than in Europe is probably not a coincidence. Again the key point that needs to be stressed is the magnitude of the aggregate income shift that has occurred in the United States since the early 1980s. The bottom 90 percent has become poorer, the top 10 percent has become richer, with an income transfer over 15 percent of US national income. This was a permanent income transfer. As Kopczuk and Saez (2010) have shown, there has been no significant rise in income mobility over the period. If the two groups perceive the shocks to be permanent and adjust their consumption accordingly, then there should have been no change in the accumulation of assets and liabilities across groups. However, if the two groups do not immediately perceive the shocks to be permanent, and/or try to resist it (for example, because they suffer a huge welfare loss if they cut their consumption too much relative to the average, as suggested by Bertrand and Morse, 2013), then this can quickly generate a very large—and unsustainable—accumulation of debt. For example, if the bottom 90 percent cuts its consumption level by the equivalent of 7.5 percent of national income (instead of 15 percent), then 10 years down the road household debt will have risen by the equivalent of 75 percent of national income—which is roughly what happened.

In any case, we find it surprising that relatively little attention has been given to the magnitude of this domestic imbalance (over 15 percent of US national income), especially as compared with the attention given to global imbalance (the 4 percent current account deficit is certainly a large deficit, but it is four times smaller). To the extent that global imbalances have put extra pressure on the US financial system, it is likely that domestic imbalances did put an even larger pressure.

Yet we feel that it would be a mistake to put too much emphasis on the top incomes/financial fragility channel: first, because rising top income shares would matter a lot even without such a channel (simply because inequality has a large impact on aggregate social welfare), and next because there are other mechanisms leading to financial fragility. There was limited rise of top income shares in Europe—and yet the financial system has clearly become more fragile over time. The rise of financial globalization and the exponential size of banking sector balance sheets have occurred pretty much everywhere and seen to bear little relationship with rising inequality. Of course, some of the European financial fragility might have been imported from the United States (itself partly driven by the rise in inequality), as was argued by a number of scholars (see in particular Acharya and Schnabl, 2010). But there also other factors that are more specifically European.

In particular, it is striking to see that the rise of aggregate private wealth/national income ratios has been particularly strong in Europe, as one can see from Figure 9 (extracted from Piketty and Zucman, 2013, who have recently collected a new historical data set of country balance sheets in order to study the long-run evolution of aggregate wealth-income ratios). There are two main channels that contribute to explain this fact.

Private Wealth/National Income Ratios, 1970–2010Source: Piketty and Zucman (2013).Authors’ computations using country national accounts.Private wealth=nonfinancial+financial assets – liabilities (household and nonprofit sectors).

First, aggregate wealth was particularly low in Europe during the 1950s–70s, both because of real effects (recovery from war destructions) and most importantly because relative asset prices were unusually low—which was largely driven by antiprivate capital policies including rent control, financial repression, and nationalization policies. This political factor was largely reversed since the 1980s–90s via financial globalization and deregulation, and large wealth transfers from public to private hands through cheap privatization. In effect, the rise of private wealth is partly due to a decline of government wealth (see Figure 10).

Private vs. Government Wealth, 1970–2010Source: Piketty and Zucman (2013).Note: Government wealth=nonfinancial+financial assets − financial liabilities (govt. sector).

Next, the rise of European wealth-income ratios is largely the consequence of high saving rates and low growth rates (mostly because of near zero population growth rates), as predicted by the one good capital accumulation model and the Harrod–Domar–Solow steady-state formula β=s/g (where β is the steady-state wealth-income ratio, s is the long-run net saving rate, and g is the long-run total growth rate, that is, the sum of population growth and productivity growth). That is, for a given saving rate s=10 percent, then the long-run wealth-income ratio β=s/g is about 300 percent if g=3 percent and about 600 percent if g=1.5 percent.

Of course, with perfect capital markets and fully diversified country portfolios, such a rise in aggregate wealth-income ratios should have no impact on financial fragility. For example, in the one good capital accumulation model with perfect capital markets, capital-output ratios should be equal between countries, so that countries with high β=s/g (owing to a combination of high saving and low population growth, such as in Japan and Europe) should invest some of their wealth in countries with relatively low β=s/g (such as the United States) and end up with large net foreign asset positions. This is partly what happens in the case of Japan (and to some extent in the case of Europe; see Piketty and Zucman, 2013, for a more detailed discussion).

However, in multisector models with heterogeneous capital and consumption goods, and with capital imperfect imperfections, high and rising wealth-income ratios can also have important implications in terms of macroeconomic fragility. That is, in case it is difficult to put the right prices on the various international capital assets, and/or in case there exists home portfolio biases (Japanese or Spanish or French savers have a very strong taste for domestic real estate or stock market), then the rise of aggregate wealth-income ratios can generate asset price bubbles and large financial volatility, as the cases of Japan and Spain—just to take two extreme examples—seem to illustrate (see Figure 11). The large rise of gross cross-border assets and liabilities can also reinforce this process.

Private Wealth/National Income, 1970–2010 (including Spain)Source: Piketty and Zucman (2013). Authors’ computations using country national accounts. Private wealth=nonfinancial assets+financial assets – financial liabilities (household and nonprofit sectors).

We certainly do not claim that the rise of wealth-income ratio is the only mechanism behind financial fragility. At a more modest level, we simply mean to suggest that this important evolution has clearly little to do with the rise of top income shares (it follows for the most part a different economic mechanism and involves different countries) and might also have played a role to exacerbate fragility. Of course, both mechanisms can very much reinforce each other.

IV. Concluding Comments

In this paper, we have argued that inequality is important. In our view, economists should devote more attention to changes in the distribution of income and wealth: first, because aggregate welfare does not derive mechanically from aggregate income and growth, and next because aggregate macro volatility might be difficult to grasp in representative agent settings. In the last decade or so, macroeconomists have made some progress in integrating cross-sectional heterogeneity and inequality into macro models (see, for example, Krueger and others, 2010). In the light of our findings, there are two ingredients that are largely missing from this literature, and that should rank highly on the future research agenda.

First, most of the rise in income inequality took place at the very top of the distribution. In order to properly account for this, one needs to introduce a richer view of the labor market. Namely, pay may not always be equal to marginal product, and changes in bargaining power can potentially play a large role, especially regarding executive compensation.

Next, in order to study the interplay between macroeconomic fragility and the distribution of income and wealth, it is critical to introduce the rise of wealth-income ratios and the rise of financial intermediation and globalization into the general picture. That is, the constant ratios described half a century ago in the “Kaldor facts” do not seem to be constant any more.

Notes

In our previous work (see, for example, Atkinson, Piketty, and Saez, 2011), our series stopped in 2007 (for the United States) or in 2005–06 (for most other countries), and thus it was impossible to analyze the impact of the Great Recession.

For a comparison between the trends obtained with administrative tax data and those obtained by scholars using CPS data (such as Burkhauser and others, 2009), see Atkinson, Piketty, and Saez (2011, Figure 11).

The WTID unfortunately does not include homogenous income composition series for all countries. However, for all countries for which we have such series (in particular Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Sweden), we find evolutions that are comparable with those depicted in Figure 4(a)–(d) for the United States (namely, a partial replacement of rent, interest and dividend income by capital gains), albeit with a lower rise of the wage share at very top income levels.

See Lansing and Markiewicz (2012) for an interesting calibrated model showing that a continuous rise in transfers along a growth path involving skill-biased technical change and rising pretax inequality can result into a Pareto improvement (all skill groups benefit from growth).

Including about two-thirds in the nonfinancial sector, and one-third in the financial sector. In contrast, the combined share of the arts, sports, and media subsectors, usually used to illustrate winner-take-all theories, is only 3.1 percent of all top 0.1 percent taxpayers. See Bakija, Cole, and Heim (2012, Table 1).

The avoidance elasticity also seems to play a role in the short run (for example, the 1986–88 blip in US top income shares is largely because of income shifting between corporate and personal income tax bases), but not too much in the longer run. See Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2013).

See Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2013). These results stand in sharp contrast to the theory posited by Gabaix and Landier (2008), according to whom the rise in CEO pay can be explained by the rise in firm size and stock market capitalization. The problem is that Gabaix and Landier only look at one country (namely, the United States). By taking a cross-country perspective, we find that firm size and equity values have risen pretty much in all developed economies, whereas top CEO pay have increased mostly in countries with low top tax rates.

References

Acharya, Viral and Philipp Schnabl, 2010, “Do Global Banks Spread Global Imbalances? The Case of Asset-Backed Commercial Paper during the Financial Crisis of 2007–09,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 58, p. 37.

Alvaredo, Facundo, Anthony Atkinson, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez, 2012, The World Top Incomes Database. Available via the Internet: http://topincomes.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/.

Atkinson, Anthony and Thomas Piketty, 2007, Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century—A Contrast Between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 585.

Atkinson, Anthony and Thomas Piketty, 2010, Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century – A Global Perspective, Vol. 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 776.

Atkinson, Anthony, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez, 2011, “Top Incomes in the Long-Run of History,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 3–71.

Azzimonti, Marina, Eva de Francisco, and Vincenzo Quadrini, 2012, “Financial Globalization, Inequality, and the Raising of Public Debt,” Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Paper, 2012.

Bakija, Jon, Adam Cole, and Bradley Heim, 2012, “Jobs and Income Growth of Top Earners and the Causes of Changing Income Inequality: Evidence from U.S. Tax Return Data,” Working Paper, Williams College, April.

Bebchuk, Lucian and Jesse Fried, 2004, Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

Bertrand, Marianne and Sendhil Mullainathan, 2001, “Are CEOs Rewarded for Luck? The Ones Without Principals Are,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 116, No. 3, pp. 901–932.

Bertrand, Marianne and Adair Morse, 2013, “Trickle-down Consumption,” NBER Working Paper No. 18883.

Burkhauser, Richard V., Shuaizhang Feng, Stephen P. Jenkins, and Jeff Larrimore, 2009, “Recent Trends in Top Income Shares in the USA: Reconciling Estimates from March CPS and IRS Tax Return Data,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 15320.

Bordo, Michael and Christopher Meissner, 2012, “Does Inequality Lead to a Financial Crisis?” NBER Working Paper.

Diamond, Peter and Emmanuel Saez, 2011, “The Case for a Progressive Tax: From Basic Research to Policy Recommendations,” CESifo Working Paper No. 3548, August, Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Gabaix, Xavier and Augustin Landier, 2008, “Why has CEO Pay Increased So Much?” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 123, pp. 49–100.

Kennickell, Arthur B., 2009, “Ponds and Streams: Wealth and Income in the U.S., 1989 to 2007,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2009–13, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Kopczuk, Wojciech, Emmanuel Saez, and Jae Song, 2010, “Earnings Inequality and Mobility in the United States: Evidence from Social Security Data since 1937,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 125, No. 1, pp. 91–128.

Krueger, D., F. Perri, L. Pistaferri, and G. Violante, 2010, “Cross-Sectional Facts for Macroeconomists,” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 13, pp. 1–14.

Kumhof, Michael and Romain Ranciere, 2010, “Inequality, Leverage and Crises,” IMF Working Paper.

Kuznets, Simon, 1953, Shares of Upper Income Groups in Income and Savings. (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research).

Lansing, K. and A. Markiewicz, 2012, “Top Incomes, Rising Inequality and Welfare,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper.

Piketty, Thomas, 2003, “Income Inequality in France, 1901–1998,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 111, No. 5, pp. 1004–1042.

Piketty, Thomas and Emmanuel Saez, 2003, “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913–1998,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118, No. 1, pp. 1–39, series updated to 2010 in March 2012.

Piketty, Thomas, Emmanuel Saez and Stefanie Stantcheva, 2013, “Optimal Taxation of Top Labor Incomes—A Tale of Three Elasticities,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, forthcoming.

Piketty, Thomas and Gabriel Zucman, 2013, “Capital is Back: Wealth-Income Ratios in Rich Countries 1700–2010,” Working Paper, Paris School of Economics.

Rajan, Raguraman and Fault Lines, 2010, University of Chicago Press.

Rotemberg, Julio, 2002, “Perceptions of Equity and the Distribution of Income,” Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 20: 249–288.

Zucman, Gabriel, 2013, “The Missing Wealth of Nations – Are Europe and the US Net Debtors or Net Creditors?” Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Additional information

*Thomas Piketty is a Professor of Economics at the Paris School of Economics. Emmanuel Saez is a Professor of Economics at the University of California of Berkeley. The authors are grateful to the editors and two referees for helpful comments.