Abstract

This research paper analyzes the role of pre-crisis reputation for quality on consumers’ perceptions of product-related dangers and company responsibility in product-harm crises with varying risk information. We consider (non-) substantiated public complaints incorporating low and moderate product-related risks, as well as product-recall situations involving serious risks to the health and safety of consumers. Hypotheses are derived from theories and concepts of consumer behavioural psychology. These are then tested empirically by using an online experiment. The effects of reputation are analyzed across different crises contexts to derive some general insights useful for crisis management. In order to shed light on situational differences of the reputation mechanism its effect on individual crisis level will also be considered. In general, the analysis finds that reputation for quality is capable of positively influencing the perceptions of company responsibility and thereby shielding the manufacturer from receiving blame. However, an established reputation for high product quality prior to the crisis fails to positively impacting consumers’ perceptions of problem severity. The crisis-specific effects of reputation turn out to be ambivalent. On the basis of these findings, recommendations to crisis managers and relevant avenues for future research are derived.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Fueled by reports on insufficient product quality and product-related risks proliferated by credible institutional sources such as RAPEX – the EU's rapid alert system for all dangerous non-food consumer products – as well as by print and electronic media public concern for quality issues is growing at an increasing rate. High-profile product recalls by Coppenrath & Wiese (cf. Standop, 2005: 125), Perrier mineral water (cf. Barton, 1991), Coca-Cola in Belgium (cf. Siegrist, 2001: 45) and Mercedes Benz A-Class (cf. Puchan, 2001) as well as the most recent foodstuffs scandals (rotten meat, SARS, bird flu, pig flue, BSE, Akrylamit) provide impressive evidence of this tendency. Quite often, public interest for product defects creates a genuine product-harm crisis for a provider accompanied by a loss in market-share and reputation. In this paper, the term crisis refers to an extraordinary situation with an uncertain outcome that, from the provider's point of view, is both exceptional and undesirable. Similarly, Ulmer, Sellnow and Seeger define an organizational crisis as a ‘specific, unexpected and non-routine event or series of events that create high levels of uncertainty and threaten or are perceived to threaten an organization's high priority goals’ (cf. Ulmer et al., 2006: 7). A product-harm crisis is an organizational crisis that directly relates to the products or services provided by the organization and, owing to its potential negative spillovers, requires an immediate decision on the corrective action to be taken (cf. Krystek, 1987: 6).

Although the provider is often publicly accused of sharing the blame for product defects, he may not be responsible for it in legal terms. Especially for small and medium-sized companies with well-known brands the situation may become very critical and could even threaten their further existence: They usually dispose of a too small marketing-budget to combat the crisis via impressive media campaigns or by offering large amounts of compensation to (alleged) victims of the crisis (cf. Grunwald, 2009: 83 ff.). Instead, for these companies crisis resolution more or less depends on their already established reputation for good product-quality in the past. Research indicates that high (as opposed to low) pre-crisis reputation is able to act as a buffer against negative publicity (cf. Dean, 2004; Dawar and Pillutla, 2000; Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994; Siomkos and Shrivastava, 1993). In conveying trust and credibility, it increases the effectiveness of any appropriate crisis response strategy and thus benefits crisis resolution. On the other hand, high levels of reputation may also be a burden to a company faced with a product-harm crisis. Due to extreme levels of consumer expectations a highly reputable company may be forced to make major concessions (eg offer larger amounts of compensation and assume responsibility) in order to manage the crisis. A crisis-specific analysis of reputation could shed light on these Janus-faced effects (cf. Coombs, 1998, 2007).

Product-harm crises typically vary according to the types of the product-related problems and risks involved. Taking account of these factors three groups of product-harm crises can be distinguished (cf. Grunwald, 2008: 3 ff.): (a) In product-recall situations a company is confronted with extremely negative information (eg by RAPEX reports) stating that its products pose serious risks to the health and safety of consumers. Product-related injuries to users of the product as well as to third parties are predominant. This situation requires a recall of the potentially dangerous products from the market. (b) In substantiated complaints situations there is negative publicity incorporating evidence that the company's products pose a functional risk to consumers. Due to malfunctioning or misuse product damages and minor physical harm to users of the product cannot be ruled out. The concerning product defects are usually covered by a product warranty or (optional contractual) guarantee. Publicized negative consumer experiences and damage reports provide examples of this crisis type. (c) In non-substantiated complaints situations consumers or consumer protection organizations publicly state their dissatisfaction and discomfort with the product quality offered. For example, neutral product testing may have found that competitors’ products offer better value for money or are easier to handle. In this situation, given the opportunity, many consumers would opt for exchanging the product. However, there is no evidence of defects, malfunctioning or product-related risks to the health and safety of consumers whatsoever.

According to prior research consumers’ perceptions of problem severity and company responsibility offer valuable starting points for effectively managing product-harm crises (cf. Grunwald, 2008: 74 ff.; Standop 2006; Tucker and Melewar, 2005; De Matos and Veiga, 2004: 3; Dean, 2004; Lyon and Cameron, 2004, 1998; Gutteling, 2001; Dawar and Pillutla, 2000; Tadelis, 1999; Coombs, 1998: 181; Dawar, 1998; Al-Najjar, 1995; Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994; Siomkos and Shrivastava, 1993; Mowen, 1980). However, the determinants mentioned above have not yet been addressed in the framework of the underlying crises situations and with regard to reputation for quality. Therefore, the purpose of the present paper is to answer the following question: What is the impact of high (as opposed to low) pre-crises reputation for product-quality on consumers’ perceptions of problem severity and company responsibility in the three types of product-harm crises defined above?

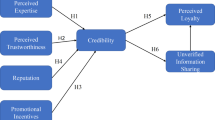

HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

A basic influence of pre-crisis reputation for quality on consumers’ perceptions of product-harm crises can be derived from theories describing the process of expectations formation (cf. Dean, 2004: 198; Dawar and Pillutla, 2000: 217 ff.). Expectations represent a standard that customers use to judge actual or perceived performances. They might refer to both desired and potential performances (cf. Bruhn, 2000: 1033; Oliver and Winer, 1987: 469 ff.). A consumer may be unable to make any final decision on quality owing to his lack of experience with the product in question. But this will not prevent him from forming expectations. According to cue utilization theory (cf. Slovic and Lichtenstein, 1971; Lichtenstein et al., 1975; Olson, 1978; Richardson et al., 1994; Stafford, 1996; Purohit and Srivastava, 2001; Helm and Mark, 2007) external information that reliably and credibly reflects a firm's conduct and product quality (eg its past reputation or product warranties offered) will be used by consumers as cues or signals that bundle or substitute other (missing) information relating to quality. Consumers use cues as long as they lack the ability to properly evaluate quality via internal information (ie by the product characteristics experienced). Such a situation is predominant for experience goods (like electronic appliances), which can only be inspected by consumers after purchase (cf. Ford et al., 1988: 239 ff.). But even then consumers may be unable to properly evaluate product quality when being recipients of a product-harm crisis. This is because they are confronted with multiple and often contradicting accounts relating to product quality (eg by the general public, media, organizations and last but not least a company's crisis communication). In such situations, consumers will not exclusively rely on their own experience with the product, which may even be positive. If credible sources like RAPEX report on product-related dangers consumers will rather attend to them (cf. Siegrist, 2001: 21).

Due to their exposure to various kinds of product-related risks in times of product-harm crises consumers often feel uncertain and long for credible information to assess these risks. Such information is necessary in order to be able to effectively evaluate product quality and thereby coping with a psychologically stressful situation (cf. Zanger et al., 2006). According to dissonance theory inconsistencies in the cognitive system (referred to as cognitive dissonances) will motivate consumers to reduce them (cf. Festinger, 1957). This is done by selectively perceiving or re-interpreting dissonant information according to their expectation standards. This so-called expectation or confirmatory bias is used as a mental strategy to regain cognitive equilibrium (harmony) or avoid imminent cognitive conflicts (cf. Conlon and Murray, 1996: 1052; Dawar and Pillutla, 2000: 217; Dean, 2004: 198; Taylor, 1982: 190–200). If consumers perceive the reputation signal as credible (ie as not contradicting with other signals relating to quality, eg warranties) it will influence their expectations in that positive (negative) reputation correlates with high (low) expectations of quality and firm conduct (cf. Dean, 2004: 198; Dawar and Pillutla, 2000: 215 ff.; Dawar, 1998: 114 ff.). According to confirmatory bias, consumers will compare the crises’ negative information on product problems and allegations of company misconduct with their expectation standards (derived from pre-crisis quality reputation). The negative information is then (re-) interpreted within the framework of perception forming (cf. Dawar and Pillutla, 2000: 217; Dawar, 1998: 114 ff.). Under conditions of pre-crisis reputation for high product quality high standards of consumer expectations will be induced. Therefore, large cognitive dissonances are to be expected when being exposed to negative contents of information that is clearly present in each product-harm crises situation. These dissonances in turn will motivate consumers to reduce them. This can be done by selectively perceiving and weighing the quality related crisis information in such a way that confirms consumers’ prior expectation standards. That is, any contradictory information (that does not ‘fit in’) tends to be ignored or inaccurately interpreted (cf. Dawar and Pillutla, 2000: 217). In contrast, a low reputation stimulus will induce low expectation standards that will merely be confirmed by the negative information contained in a product-harm crisis. In this case no cognitive dissonance is to be expected. Therefore, no confirmatory bias effect will set in and unimproved or even worse consumer reactions towards the crisis prevail (cf. Maxham and Netemeyer, 2002: 57 ff.). In accordance with this line of argumentation, Su/Tippins find evidence that reputation for high quality makes the manufacturer a less plausible cause of product failure and shields him from receiving blame (cf. Su and Tippins, 1998: 141). In turn, lower (better) perceptions of company responsibility are to be expected, which is summarized in Hypothesis 1:

H1:

-

Pre-crisis reputation for quality moderates consumers’ reactions to product-harm crises: Consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility will be higher with low than with high quality reputation in product-recall situations, substantiated and non-substantiated complaints situations.

With respect to consumers’ perceptions of problem severity Siomkos and Kurzbard (1994) find support that consumers, on average, perceive product defects as less dangerous in a crisis involving a high-reputation company in contrast to a low-reputation company (cf. Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994: 34). From the argumentation outlined above the following hypothesis can be derived concerning perceived problem severity:

H2:

-

Pre-crisis reputation for quality moderates consumers’ reactions to product-harm crises: Consumers’ perceptions of problem severity will be higher with low than with high quality reputation in product-recall situations, substantiated and non-substantiated complaints situations.

In particular, pre-crisis reputation becomes increasingly important as a signal of quality in times of product-harm crises if the possible damage due to product defects is also high. This holds because in this case consumers will be confronted with a severe perceived uncertainty concerning quality (cf. Büschken, 1999: 15). According to cue utilization and signalling theories, a risen uncertainty is accompanied by a higher need for external information (like reputation) in order to effectively evaluate quality and thereby reduce perceived uncertainty (cf. Spremann, 1988: 619 f.; Gerhard, 1995: 146). The product problems picked out as a central theme in product-recall situations allow to expect higher perceived problem severity than in substantiated complaints situations. The same holds comparing substantiated with non-substantiated complaints situations. This is due to an increasing range of risks or potential of loss involved and has been termed negativity effect or negativity bias (cf. Mizerski, 1982: 303; Niemeyer, 1993: 12; Taylor, 1991: 70). The argument outlined above is well-grounded on crisis signal theory, which posits that the effects of a single crisis event depend on its underlying signal potential. The signal potential of a crisis event is larger the more it heralds severe future problems (ie risks), although the current problems may be of a quite limited nature (cf. Jungermann and Slovic, 1993: 93 f.; Balderjahn and Mennicken, 1994: 13; Alvensleben and Kafka, 1999: 5 f.; Grunwald, 2008: 99 ff.). Higher levels of perceived problem severity and consequently higher uncertainty are to be expected in product-recall situations relative to substantiated complaints situations and in substantiated relative to non-substantiated complaints situations. Therefore, the need for external (easily detectable and credible) quality-related information such as pre-crisis reputation for quality will be lowest in non-substantiated complaints situations and highest in product-recall situations. Hence, the impact of high (as opposed to low) pre-crisis quality reputation on consumers’ perceptions of problem severity will be as summarized by Hypothesis 3:

H3:

-

Pre-crisis reputation for quality moderates consumers’ reactions to product-harm crises: In product-recall situations (substantiated complaints situations) high as opposed to low quality reputation leads to lower perceptions of problem severity than in substantiated (non-substantiated) complaints situations.

According to attribution theory, individuals tend to form causal attributions for events they experience (cf. Heider, 1958; Kelley, 1973). This holds especially for those events that are negative (cf. Weiner, 1986). Therefore, with increasing perceived problem severity a higher attributional activity of consumers can be predicted. According to the negativity bias this results in more extreme and polarizing consumer reactions concomitant with higher levels of perceived company responsibility (cf. Niemeyer, 1993: 28 f.; Mizerski, 1982). In accordance with this argument, attributional discounting principle (cf. Kelley, 1972, 1973); Mizerski, 1982: 302) suggests that consumers less likely tend to be discounting company related causes for a product-harm crisis when being exposed to extremely negative events such as product-recall situations (cf. Folkes and Patrick, 2001: 27; Su and Tippins, 1998: 142; Laufer et al., 2005: 33 ff.; Silvera and Laufer, 2005: 22).

Due to a higher negative valence of the crisis information provided in product-recall situations compared to substantiated or even non-substantiated complaints situations, consumers will perceive an increasing discrepancy or inconsistency of information. This leads to a larger cognitive dissonance when the incremental negative information coincides with a high reputation stimulus that is identical in each crisis situation (cf. Kroeber-Riel and Weinberg, 1996: 184). Moreover, consumers will be less expecting a high-reputation company to be involved in a product-harm crisis incorporating serious consumer risks (like a product-recall situation) than in a crisis dominated by moderate or low product-related risks (ie in a public complaints situation). As the cognitive dissonance experienced by consumers will be larger in product-recall situations than in substantiated or non-substantiated complaints situations, the evolving confirmatory bias effect on consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility will also be highest in product-recall situations and lowest in non-substantiated complaints situations. Therefore, the (differential) impact of pre-crisis quality reputation as an expectation standard to re-interpret a given crisis event in light of this standard will be larger in product-recall situations as compared to substantiated complaints situations. The same holds for the comparison between substantiated and non-substantiated complaints situations. That said, the motivation to discount any dissonant information under conditions of reputation for high product quality will be largest in product-recall situations and lowest in non-substantiated complaints situations. Therefore, pre-crisis reputation for high quality will interact with the respective crisis situation, that is, both factors cannot be regarded as independent in their impact on perceived company responsibility. The opposite holds true for conditions of low quality reputation prior to the crisis. Under this condition no interaction effect is to be predicted. This holds because the low reputation stimulus expectedly coincides with the negative content of information provided by each crisis situation. Due to a lack of cognitive dissonance no motivated reasoning of consumers in accordance with the confirmatory bias effect will set in. The quality-related negative information present in each crisis situation will only confirm consumers’ low expectations of the provider's quality and conduct. This holds true for all three types of crises situations considered here. From this, the following hypothesis can be derived with respect to consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility:

H4:

-

Pre-crisis reputation for quality moderates consumers’ reactions to product-harm crises: In product-recall situations (substantiated complaints situations) high as opposed to low quality reputation leads to lower perceptions of company responsibility than in substantiated (non-substantiated) complaints situations.

RESEARCH DESIGN

An experimental 3×2-between-subject-design with an online-representative sample of N=600 customers (potential users of the product) conducted 2006 in Germany is used to determine the effects of pre-crisis reputation for high vs low quality on consumer reactions within the context of the three different product-harm crises situations outlined above. The product-recall scenario incorporates serious risk information passed to the recipients. This was done by confronting them with a fictitious product-recall from consumers ordered by a regulatory authority. In addition, they were presented a newspaper article reporting an allegedly product-related severe but non-fatal consumer accident (a broken leg) requiring hospital treatment. The substantiated complaints scenario comprises a product-defect posing a functional risk to consumers, which is typically covered by warranty or (contractual) guarantee law. Due to malfunctioning or misuse product damages and minor physical harm cannot be ruled out. In the non-substantiated complaints scenario consumers were informed by a magazine report that many consumers are discontented with the product they bought and would like to change it if they could. Besides, the product obtained only below average ratings by neutral product testing regarding its price-quality-ratio and easy handling. However, there is no indication that the product poses a danger to the health or safety of consumers. Consumer durables (bicycles) were used in each scenario to realistically reflect potential sources of the product-related risks characteristic for each crisis situation. A hypothetical brand name (‘Century’) was chosen in order to control for any brand-specific consumer knowledge that may distort their evaluations thus posing a threat to internal validity of results.

The reputation stimulus was varied in two ways in the scenarios: the high reputation company is known for its good conduct and high standards of production in the past as can be derived from its positive claims record and publicized damage reports. No major incident has happened so far that could be traced back to the company's negligence to produce or sell non-reliable or dangerous products. Besides, the company offers its products with a warranty that exceeds market standards (cf. Tolle, 1994; Spremann, 1988). On the contrary, the low reputation company is known for producing below average quality and has been subject to public investigations of violating production standards in the past. Only standard warranties are offered that merely comply with the market regulations.

Each of the two dependent variables (perceived problem severity and perceived company responsibility) is operationalized by four items measured on a Likert-type six-point scale (1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree and vice versa). Due to high levels of correlation between the items representing a variable all respective item scores are aggregated to a mean score for each dependent variable. Chronbach's Alpha Coefficient indicates high reliability for the scale used to measure perceived problem severity (0.982) and satisfactory reliability with regard to the measurement of perceived company responsibility (0.800). The dependent variable operationalizations are depicted in Table 1.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the underlying experimental 3×2-between-subject-design.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Hypotheses 1 and 2 are tested using independent samples t-tests in order to compare consumers’ reactions under conditions of pre-crisis reputation for low vs. high quality across all crises situations. To empirically test Hypotheses 3 and 4 two-factor analyses of variance are conducted (cf. Eschweiler et al., 2007: 14). Since dependent variable correlation is not predominant univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) for each dependent variable are used. In this case multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) leads to the same interpretations as its univariate counterpart (cf. Bühl and Zöfel, 2005: 414). Conducted Levene tests on homogeneity of variance show non-significant results (p>0.05), that is, the experimental groups can be considered as homogeneous. For each effect Partial Eta-Squared is calculated to estimate the relative importance weight of each factor or factor combination (interaction) (cf. Herrmann and Seilheimer, 1999: 287; Bortz, 1999: 269 f., 289; Bühl and Zöfel, 2005: 406, 408). The coefficient of determination (R-Squared) indicates how much of the dependent measures’ variance can be explained by the model (cf. Bühl and Zöfel, 2005: 408). Profile plots are provided to interpret significant interaction effects (cf. Bortz, 1999: 289 ff.; Herrmann and Seilheimer, 1999: 285 f.). Additionally, dependent variable means and differences between means are calculated for each crisis situation at both reputation levels and vice versa and statistically tested on significance using independent samples t-tests.

Table 3 displays means of perceived problem severity and company responsibility for both reputation groups. In addition, the average means for all experimental groups are shown in the last column. As predicted, all group means indicate lower (ie better) levels of perceived problem severity and company responsibility under conditions of high opposed to low reputation and in comparison with the aggregated group means. However, the group differences are only significant with respect to consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility (t=−11,085, df=598, p<0.01) but not with regard to perceived problem severity (t=−0.779, df=598, p=0.436). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 cannot be rejected as opposed to Hypothesis 2.

Accordingly, the reputation factor seems to moderate (mollify) consumers’ attributions of blame towards the manufacturer in all the product-harm crises jointly considered but fails to moderate them in terms of problem evaluation. That is, reputation for high as opposed to low quality effectively shifts consumers’ reactions to the benefit of crisis management regarding perceptions of company responsibility but not with respect to perceived problem severity.

Table 4 displays the ANOVA results for the dependent variable ‘perceived problem severity’ relating to the test of Hypothesis 3.

As can be seen from Table 4 50.4 percent of the dependent variable's variance can be explained by the model (R-Squared=0.504) and primarily by the crisis situation main factor (Partial Eta-Squared=0.503) which is highly significant (p<0.001). Both the reputation main factor (p=0.271) as well as its interaction with the situation factor (p=0.804) fail to significantly influence consumers’ perceptions of problem severity. However, the reputation factor and its interaction with the crisis situation are only able to explain a very small proportion of variance of perceived problem severity. These results shed light on a strong negativity bias to be present in the underlying crises situations that effects consumers’ perceptions of problem severity. This effect leads crises’ recipients to disregard any positive or negative reputation signal in each crisis situation. This finding accords with the results of the aggregated (cross-crises) analysis regarding Hypothesis 2. For the evaluation of problem severity reputation seems to be a negligible factor, that is perceived problem severity is independent of the provider's pre-crisis reputation for quality. High as opposed to low reputation does not lead to any different perceptions of problem severity. This can also be seen from the profile plots depicted in Figure 1. Parallel lines connecting the corresponding means indicate a lack of interaction.

Also the non-significant differences between the two reputation groups can be seen from the profile plots as well as from the t-test results shown in Table 5. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 cannot be sustained.

Table 6 shows the ANOVA results for ‘perceived company responsibility’ relating to Hypothesis 4. As can be seen from Table 6, the reputation and situation main effects are highly significant (p<0.001). The reputation factor is able to explain 22.1 percent, the situation factor 26.1 percent of consumers’ perception of company responsibility. The significant interaction of the two factors contributes only 3.1 percent to explaining perceived company responsibility. The total model explains 40.1 percent of variance indicating a medium explanatory power.

The type of the interaction effect found in the data can be closer examined by inspecting the profile plots depicted in Figure 2. The lines connecting the means are not parallel which indicates an interaction between the reputation and situation factors. Since the poly lines in both the upper and lower part of the profile plot show the same trend the interaction can be characterized as ordinal (cf. Bortz, 1999: 290 f.; Herrmann and Seilheimer, 1999: 285 f.). That said, the impact of reputation on perceived company responsibility varies in each crisis situation. However, the rank order of the effects does not change.

The rank order of the situation factor levels is identical for each high and low reputation level; the rank order of the reputation factor levels remains the same for all three levels of the situation factor. Therefore, both main effects can be clearly interpreted. As can be seen from Figure 2 consumers attribute more responsibility to a low reputation provider than to a high reputation provider. This holds true for all three crises situations. The respective means and differences between means for ‘perceived company responsibility’ are depicted in Table 7.

The results indicate that higher levels of reputation are able to effectively attenuate the negative influence of crises situations with serious risk information (ie product-recall situations) on consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility. But also in crises situations involving medium to low consumer risks high reputation for quality (Meansub−comp=3.56; Meannon−sub−comp=2.33) as opposed to low reputation (Meansub−comp=4.15; t=−4.165; p<0.001; Meannon−sub−comp=3.70; t=−10.558; p<0.001) is able to induce lower (ie better) levels of perceived company responsibility. Under conditions of high reputation the respective means differ significantly between the three crises situations (p<0.05). The same effect holds true under conditions of low reputation (p<0.002). The underlying interaction effect and its relative power in various product-harm crises can be estimated by inspecting the distances of the respective connection lines in the profile plot (cf. Bortz, 1999: 290; Goodwin and Ross, 1992: 155 ff.; Mowen and Ellis, 1981: 167 f.). The pattern of interaction elucidates that reputation for high quality more strongly reduces consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility in non-substantiated complaints and product-recall situations both compared to substantiated complaints situations (see Figure 2 above). However, Hypothesis 4 postulates a stronger attenuating effect of high vs. low reputation on perceptions of company responsibility in product-recall situations as in substantiated complaints situations on the one hand and in substantiated complaints situations in comparison with non-substantiated complaints situations on the other. According to the pattern of the interaction effect found in the empirical data Hypothesis 4 cannot be upheld completely but only in part with respect to the difference between product-recall and substantiated complaints situations.

DISCUSSION AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

In all of the product-harm crises situations considered reputation for high as opposed to low quality succeeds in protecting a company from harsh allegations of responsibility and attributions of blame. At the same time reputation for high quality fails to impact consumers’ perceptions of problem severity in a positive way. This finding may be explained in that the company's reputation for quality is seen as more closely related to the company itself and its conduct than to the surrounding crisis situation characterized by product problems and inherent risks. Therefore, if influencing consumers’ perceptions of problem severity is considered essential for crisis resolution crises managers cannot exclusively rely on the company's already established reputation for good product quality. In this case, established reputation for high product quality does not present the cure. This holds for all crises situations considered here because there is no significant interaction between the reputation factor and the crisis situation.

However, in this case choosing the right communication content becomes an essential part of selecting an appropriate crisis response strategy (cf. Coombs, 1995). In general, crisis communication intends ‘to prevent or lessen the negative outcomes of a crisis and thereby protect the organization, stakeholders and/or industry from damage (cf. Coombs, 1999: 4). Choosing the right message is important because there is some experimental evidence that communication has indeed the potential to alter attributions in a favourable way (cf. Coombs and Holliday, 1996). Research into crisis communication suggests that the communication content should be directed at questioning the respective consumer problem (cf. Coombs, 2007: 170 ff.). This can be done, for example, by simply denying the existence of a crisis, by blaming persons outside the company for the crisis, by claiming the company's inability to control the events that triggered the crisis or by downplaying its consequences for consumers. Of course the message has to be credible to promote believability and effectiveness (cf. Reynolds and Seeger, 2005: 45).

The negativity effect induced by the crises situations apparently foils confirmatory bias in a way that motivates consumers to evaluate product-harm crises solely according to their inherent characteristics (ie by the degree of substantiation of the product-related problems and evolving risks). Nevertheless, the results of the conducted experiment also indicate that reputation for low quality prior to the crisis does not contribute to any deteriorating of consumers’ perceptions of problem severity.

As compared to the effect of pre-crisis quality reputation on perceptions of problem severity this factor apparently seems to exert a larger (significant) impact on consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility. Besides, this influence seems to be as strong as the crisis situational impact itself. The positive effects of reputation apparently are not foiled by a dominating negativity effect of the crises situations like in the case of perceived problem severity. In contrast, the already established reputation for high quality seems to act in favour of crisis management by way of creating a better starting position for the implementation of crisis response strategies. From the producer's viewpoint high as opposed to low quality reputation is able to induce a more favourable attributional activity of consumers in all three crises situations. Although the interaction of the situation and reputation factors is significant it hardly contributes to explaining consumers’ attribution of responsibility. However, the profile plot used to test Hypothesis 4 indicates a relatively larger positive effect of reputation on perceived company responsibility in crises situations incorporating serious and low consumer risks as compared to crises comprising medium level product-related risks (like in the case of substantiated complaints situations). Therefore, the power of the reputational effect on consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility can be approximated by a U-shaped form which is depicted in Figure 3.

The relatively lower impact of reputation on perceptions of company responsibility in the setting of substantiated public complaints may be explained by a compensatory effect of the legal aspects of this type of crisis involving manifest product-related problems. In this situation, consumers may feel more protected regarding their opportunity to asserting claims on the grounds of perceived warranty (or guarantee) rights. That is, they less intensively need to rely on other signals of trust and quality like the provider's reputation. From this, a weakening of consumers’ attributional activities can be derived which results in lower (ie better) levels of perceived company responsibility. In turn, they less strongly require a positive reputation signal. There seems to be a substitutional relationship between reputation and warranties as quality signals (cf. Price and Dawar, 2002; Purohit and Srivastava, 2001; Innis and Unnava, 1991; Gerhard, 1995: 163 ff.; Ungern-Sternberg, 1984; Al-Najjar, 1995: 605 ff.; Balachander, 2001: 1282 ff. 172). Nevertheless, the fact that consumers strongly perceive their warranty rights under conditions of substantiated complaints situations does not automatically render reputation for high quality obsolete. However, its significance will be reduced as consumers increasingly use other information to evaluate a provider faced with this type of crisis situation.

CONCLUSION

This research paper analyzes the effects of pre-crisis reputation for quality on consumers’ perceptions of three typical product-harm crises that vary according to their inherent product-related problems and evolving risks. Some important conclusions arise for managing product-harm crisis. With respect to consumers’ perceptions of problem severity, the positive reputation signal fails to act in favour of crisis management. In view of the negligible influence of pre-crisis quality reputation on the perception of product problems, adequate crises response strategies become increasingly important. In order to effectively weaken the negative valence of information inherent in each crises situation simply relying on a company's already established reputation for high product quality is not enough. If a positive shift of consumers’ perceptions of problem severity is considered crucial for crisis resolution, for example, for keeping up ones’ positive image or positioning as a manufacturer of high safety products, the results reported in this paper call for active corrections. Besides, the impact of reputation on consumers’ perceptions of product-related dangers is not different in product-recall situations (incorporating serious risks to the health and safety of consumers) from substantiated complaints situations (involving manifest product problems capable of evoking a large quantity of warranty claims) and non-substantiated complaints situations (revealing consumers’ dissatisfaction in the absence of manifest product-related problems or serious risks). Therefore, crisis management does not need to consider a varying crisis-specific influence of reputation in choosing the adequate crisis response strategy to counter negative perceptions of problem severity.

Concerning consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility for the respective product-related problems and risks a significant moderating influence of reputation can be detected. In each of the crises situations discussed pre-crisis reputation for high as opposed to low quality is able to improve consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility considerably. Besides, pre-crisis reputation for high product quality seems to reduce consumers’ perceptions of company responsibility more strongly in non-substantiated comp-laints and product-recall situations both in comparison with substantiated complaints situations. Therefore, an already established reputation for high product quality in the past will be relatively less effective in protecting or improving ones’ public image of being innocently driven into a substantiated complaints crisis. In order to improve consumers’ perceptions of responsibility in this type of crisis situation a provider could adopt a communication strategy of excuse. Such a strategy implies agreeing on problem existence while at the same time denying (eg shifting or downplaying) company responsibility (cf. Grunwald, 2008: 56 ff.).

Future research should further examine the effects of pre-crisis reputation on different types of consumer groups as recipients of the crises events outlined in this study. For example, consumers could be segmented according to their degree of crisis involvement or whether they are directly (like buyers or users) or only indirectly (like third parties) affected by the product-related problems and evolving risks. In addition to analyzing the role of reputation for quality also other forms of reputation (eg corporate social responsibility) should be addressed by future research as potential moderators of negative consumer reactions to various product-harm crises (cf. eg Becker-Olsen et al., 2006; Dean, 2004). Especially, examining the joint effects of various forms of reputation could provide valuable insights for practitioners engaged in product-harm crises management.

References

Al-Najjar, N.I. (1995) ‘Reputation, product quality, and warranties’, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 3, 605–637.

Alvensleben, v.R. and Kafka, C. (1999) ‘Grundprobleme der Risikokommunikation und ihre Bedeutung für die Land- und Ernährungswirtschaft’, Working Paper, University of Kiel (Germany).

Balachander, S. (2001) ‘Warranty signalling and reputation’, Management Science, 47 (9), 1282–1289.

Balderjahn, I. and Mennicken, C. (1994) ‘Der Umgang von Managern mit ökologischen Risiken und Krisen: Ein verhaltenswissenschaftlicher Ansatz’, Lehr- und Forschungsbericht Nr. 2, Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliche Fakultät, Lehrstuhl für Betriebswirtschaftslehre mit dem Schwerpunkt Marketing, University of Potsdam (Germany).

Barton, L. (1991) ‘A case study in crisis management: The Perrier recall’, Industrial Management & Data Systems, 91 (7), 6–8.

Becker-Olsen, K.L., Cudmore, B.A. and Hill, R.P. (2006) ‘The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behaviour’, Journal of Business Research, 59 (1), 46–53.

Bortz, J. (1999) Statistik für Sozialwissenschaftler, 5th edn., Springer, Berlin et al., Germany.

Bruhn, M. (2000) ‘Kundenerwartungen – Theoretische Grundlagen, Messung und Managementkonzept’, Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, 70 (9), 1031–1054.

Bühl, A. and Zöfel, P. (2005) SPSS 12 – Einführung in die moderne Datenanalyse unter Windows, 9th edn., Pearson, Munich, Germany.

Büschken, J. (1999) ‘Wirkung von Reputation zur Reduktion von Qualitätsunsicherheit’, Working Paper No. 123, Katholische Universität Eichstätt, Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät Ingolstadt, Ingolstadt (Germany).

Conlon, D.E. and Murray, N.M. (1996) ‘Customer perceptions of corporate responses to product complaints: The role of explanations’, Academy of Management Journal, 39 (4), 1040–1058.

Coombs, W.T. (1995) ‘Choosing the right words: The development of guidelines for the selection of the appropriate response strategies’, Management Communication Quarterly, 8 (4), 447–476.

Coombs, W.T. (1998) ‘An analytic framework for crisis situations: Better responses from a better understanding of the situation’, Journal of Public Relations Research, 10 (3), 177–191.

Coombs, W.T. (1999) Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Coombs, W.T. (2007) ‘Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory’, Corporate Reputation Review, 10 (3), 163–176.

Coombs, W.T. and Holliday, S.J. (1996) ‘Communication and attributions in a crisis: An experimental study in crisis communication’, Journal of Public Relations Research, 8 (4), 279–295.

Dawar, N. (1998) ‘Product-harm crises and the signaling ability of brands’, International Studies of Management & Organization, 28 (3), 109–119.

Dawar, N. and Pillutla, M.M. (2000) ‘Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations’, Journal of Marketing Research, 37, 215–226.

Dean, D.H. (2004) ‘Consumer reaction to negative publicity: Effects of corporate reputation, response, and responsibility for a crisis event’, Journal of Business Communication, 41 (2), 192–211.

Eschweiler, M., Evanschitzky, H. and Woisetschläger, D. (2007) ‘Laborexperimente in der Marketingwissenschaft – Bestandsaufnahme und Leitfaden bei varianzanalytischen Auswertungen’, Working Paper No. 45, Förderkreis für Industriegütermarketing e.V. an der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster (ed. Prof. Dr Dr h.c. Klaus Backhaus), Münster (Germany).

Festinger, L. (1957) A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, USA.

Folkes, V.S. and Patrick, V. (2001) ‘Consumers’ perceptions of blame in the firestone tire recall’, Marketing and Public Policy Conference Proceedings, 11, 26–33.

Ford, G.T., Smith, D.B. and Swasy, J.L. (1988) ‘An empirical test of the search, experience and credence attributes framework’, Advances in Consumer Research, 15, 239–243.

Gerhard, A. (1995) Die Unsicherheit des Konsumenten bei der Kaufentscheidung: Verhaltensweisen von Konsumenten und Anbietern, Gabler, Wiesbaden, Germany.

Goodwin, C. and Ross, I. (1992) ‘Consumer responses to service failures: Influence of procedural and interactional fairness perceptions’, Journal of Business Research, 25, 149–163.

Grunwald, G. (2008) Die Bewältigung von Produktkrisen: Ein Vergleich von Beschwerde-, Reklamations- und Rückrufsituationen, Eul, Lohmar – Köln, Germany.

Grunwald, G. (2009) ‘Produktkrisenmanagement bei kleinen und mittleren Unternehmen – Eine empirische Analyse zum Einsatz kommunikationspolitischer Instrumente’, in J.-A. Meyer, (ed.), Management-Instrumente in kleinen und mittleren Unternehmen – Jahrbuch der KMU-Forschung und -Praxis, Eul, Lohmar – Köln, Germany, pp. 83–98.

Gutteling, J.M. (2001) ‘Current views on risk communication and their implications for crisis and reputation management’, Document Design, 2 (3), 236–246.

Heider, F. (1958) The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations, Wiley, New York.

Helm, R. and Mark, A. (2007) ‘Implications from cue utilisation theory and signalling theory for firm reputation and the marketing of new products’, International Journal of Product Development, 4 (3/4), 396–411.

Herrmann, A. and Seilheimer, C. (1999) ‘Varianz- und Kovarianzanalyse’, in A. Herrmann and C. Homburg (eds.), Marktforschung: Methoden, Anwendungen, Praxisbeispiele, Gabler, Wiesbaden, Germany, pp. 265–294.

Innis, D.E. and Unnava, H.R. (1991) ‘The usefulness of product warranties for reputable and new brands’, Advances in Consumer Research, 18, 317–322.

Jungermann, H. and Slovic, P. (1993) ‘Charakteristika individueller Risikowahrnehmung’, in B. Rück (ed.), Risiko ist ein Konstrukt, Reihe, Gesellschaft und Unsicherheit, Vol. 2, Knesebeck, Munich, Germany, pp. 89–108.

Kelley, H.H. (1972) ‘Causal schemata and the attribution process’, in E.E. Jones, D.E. Kanouse, H.H. Kelley, R.E. Nisbett, S. Valins and B. Weiner (eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the Causes of Behaviour, General Learning Press, Morristown, N.J., USA, pp. 1–24.

Kelley, H.H. (1973) ‘Processes of causal attribution’, American Psychologist, 28 (February), 107–128.

Kroeber-Riel, W. and Weinberg, P. (1996) Konsumentenverhalten, 6th edn., Vahlen, Munich, Germany.

Krystek, U. (1987) Unternehmenskrisen: Beschreibung, Vermeidung und Bewältigung überlebenskritischer Prozesse in Unternehmungen, Gabler, Wiesbaden, Germany.

Laufer, D., Gillespie, K., McBride, B. and Gonzales, S. (2005) ‘The role of severity in consumer attributions of blame defensive attributions in product-harm crises in Mexico’, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 17, 33–50.

Lichtenstein, S., Earle, T.C. and Slovic, P. (1975) ‘Cue utilization in a numerical prediction task’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 104, 77–85.

Lyon, L. and Cameron, G.T. (1998) ‘Fess up or stonewall? An experimental test of prior reputation and response style in the face of negative news coverage’, Web Journal of Mass Communication Research, 1, http://www.scripps.ohiou.edu/wjmcr/vol01/1-4a-B.htm.

Lyon, L. and Cameron, G.T. (2004) ‘A relational approach examining the interplay of prior reputation and immediate response to a crisis’, Journal of Public Relations Research, 16 (3), 213–224.

De Matos, C.A. and Veiga, R.T. (2004) ‘The effects of negative publicity and company reaction on consumer attitudes’, Working Paper, Center for Management Research and Postgraduate Courses, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Maxham III, J.G. and Netemeyer, R.G. (2002) ‘A longitudinal study of complaining customers’ evaluations of multiple service failures and recovery efforts’, Journal of Marketing, 66, 57–71.

Mizerski, R.W. (1982) ‘An attribution explanation of the disproportionate influence of unfavorable information’, Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 301–367.

Mowen, J.C. (1980) ‘Further information on consumer perceptions of product recalls’, Advances in Consumer Research, 7, 519–523.

Mowen, J.C. and Ellis, H.W. (1981) ‘The product defect: Managerial considerations and consumer implications’, in B. Enis and K. Roaring (eds.), The Annual Review of Marketing, American Marketing Association, Chicago, pp. 158–172.

Niemeyer, H.-G. (1993) Begründungsmuster von Konsumenten: Attributionstheoretische Grundlagen und Einflussmöglichkeiten im Marketing, Springer, Heidelberg, Germany.

Oliver, R.L. and Winer, R.S. (1987) ‘A framework for the formation and structure of consumer expectations: Review and propositions’, Journal of Economic Psychology, 8, 469–499.

Olson, J.C. (1978) ‘Inferential belief formation in the cue utilization process’, Advances in Consumer Research, 5 (1), 706–713.

Price, L.J. and Dawar, N. (2002) ‘The joint effects of brands and warranties in signaling new pro-duct quality’, Journal of Economic Psychology, 23, 165–190.

Puchan, H. (2001) ‘The Mercedes-Benz A-class crisis’, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 6 (1), 42–46.

Purohit, D. and Srivastava, J. (2001) ‘Effect of manufacturer reputation, retailer reputation and product warranty on consumer judgements of product quality: A cue diagnostic framework’, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 10 (3), 123–134.

Reynolds, B. and Seeger, M.W. (2005) ‘Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integr-ative model’, Journal of Health Communication, 10, 43–55.

Richardson, P.S., Dick, A.S. and Jain, A.K. (1994) ‘Extrinsic and intrinsic cue effects on perceptions of store brand quality’, Journal of Marketing, 58, 28–36.

Siegrist, M. (2001) ‘Die Bedeutung von Vertrauen bei der Wahrnehmung und Bewertung von Risiken’, Arbeitsbericht Nr. 197, Akademie für Technikfolgenabschätzung in Baden Württemberg, Stuttgart, Germany.

Silvera, D.H. and Laufer, D. (2005) ‘Recent developments in attribution research and their implications for consumer judgments and behavior’, Working Paper, The University of Tromsø/Norway; University of Cincinnati, Ohio/USA.

Siomkos, G. and Kurzbard, G. (1994) ‘The hidden crisis in product-harm crisis management’, European Journal of Marketing, 28 (2), 30–41.

Siomkos, G. and Shrivastava, P. (1993) ‘Responding to product liability crises’, Long Range Planning, 26 (5), 72–79.

Slovic, P. and Lichtenstein, S. (1971) ‘Comparison of Bayesian and regression approaches to the study of information processing in judgement’, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6, 649–744.

Spremann, K. (1988) ‘Reputation, garantie, information’, Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, 58 (5/6), 613–629.

Stafford, M.R. (1996) ‘Tangibility in services advertising: An investigation of verbal versus visual cues’, Journal of Advertising, 25 (3), 13–28.

Standop, D. (2005) ‘Rückrufsituationen: Entscheidungsanalyse und die Frage bilanzieller Rückstellungen’, in O.A. Altenburger (ed.), Rechnungswesen, Revision und Steuern, Vol. 1: Reformbedarf bei der Abschlussprüfung – Umstrittene Rückstellungen, Linde, Vienna, Austria, pp. 119–143.

Standop, D. (2006) ‘Der Verlust von Konsumentenvertrauen gegenüber Anbietern: Der Fall von Produktrückrufen’, in H. Bauer, M. Neumann and A. Schüle (eds.), Konsumentenvertrauen: Konzepte und Anwendungen für ein nachhaltiges Kundenbindungsmanagement, Vahlen, Munich, Germany, pp. 95–104.

Su, W. and Tippins, M.J. (1998) ‘Consumer attributions of product failure to channel members and self: The impact of situational cues’, Advances in Consumer Research, 25, 139–145.

Tadelis, S. (1999) ‘What's in a name? Reputation as a tradeable asset’, The American Economic Review, 89 (3), 548–563.

Taylor, S.E. (1982) ‘The availability bias in social perception’, in D. Kahneman, P. Slovic and A. Tversky (eds.), Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, pp. 190–200.

Taylor, S.E. (1991) ‘Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative events: The mobilization-minimization hypothesis’, Psychological Bulletin, 110 (1), 67–85.

Tolle, E. (1994) ‘Informationsökonomische Erkenntnisse für das Marketing bei Qualitätsunsicherheit der Konsumenten’, Zeitschrift für betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, 46 (11), 926–938.

Tucker, L. and Melewar, T.C. (2005) ‘Corporate reputation and crisis management: The threat and manageability of anti-corporatism’, Corporate Reputation Review, 7 (4), 377–387.

Ulmer, R.R., Sellnow, T.L. and Seeger, M.W. (2006) Effective Crisis Communication: Moving from Crisis to Opportunity, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

von Ungern-Sternberg, T.R. (1984) Zur Analyse von Märkten mit unvollständiger Nachfragerinformation, Springer, Berlin, Germany.

Weiner, B. (1986) An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotions, Springer, New York.

Zanger, C., Gaus, H. and Weißgerber, A. (2006) ‘Markenbeziehung und Konsumentenreaktion auf negative Medieninformationen’, Working Paper, Lehrstuhl für Marketing und Handelsbetriebslehre der Technischen Universität Chemnitz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grunwald, G., Hempelmann, B. Impacts of Reputation for Quality on Perceptions of Company Responsibility and Product-related Dangers in times of Product-recall and Public Complaints Crises: Results from an Empirical Investigation. Corp Reputation Rev 13, 264–283 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2010.23

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2010.23