Abstract

This paper examines the use of more extensive risk classification and its impact on annuitisation values in consumer markets with mortality heterogeneity. Prices of U.S. retail annuities do not currently reflect buyers’ attributes other than age and sex. I qualitatively assess a number of proposed underwriting factors and show that the factors chosen can robustly predict mortality heterogeneity in a hazards framework. The relative value of annuities across demographic groups converges considerably under finer-grained pricing, but the change in consumers’ well-being is asymmetric. Shorter-lived annuitants gain about 30 per cent in financial and utility-adjusted terms, whereas longer-lived annuitants experience losses of 16 per cent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For instance, Mitchell et al. (1999) estimate that annuity prices are approximately 10 per cent higher after U.S. insurers take into account selection effects and price using annuitant mortality tables that assume above-average longevity. Adverse selection arises from the asymmetric information between individuals and insurers about life expectancies.

These studies, in turn, draw on a broader literature that has examined key determinants of mortality differentials in the U.S. population. Such risk factors include socio-demographic attributes like race and marital status (Sorlie et al., 1992; Preston et al., 1996; Dupre et al., 2009); socio-economic indicators like education, income, wealth, occupation (Mirowsky and Ross, 2000; Deaton and Paxson, 2001; Delavande and Rohwedder, 2011); health-related factors (Idler and Angel, 1990; Hurd and McGarry, 2002; Mehta et al., 2003; Mehta and Chang, 2009); and behavioural factors like smoking habits (Cutler and Lleras-Muney, 2008).

Low-income individuals are more likely to experience higher mortality rates but it is also true that poor health individuals with high mortality are unable to earn a high income.

For example, how to classify individuals who have two addresses.

Risk classification is widely used in other insurance markets to group consumers with similar risk characteristics so as to flexibly price policies. For example, life insurance is priced based on characteristics like occupation, health status, participation in hazardous activities and lifestyle factors. Applicants are typically individually interviewed and examined by a medical practitioner. Health insurance is also extensively underwritten based on smoking behaviour, past and current medical conditions, diet, exercise and other factors.

In comparison, the market segment for medically underwritten annuities in the U.S. is small; this is in part because such products are only available to individuals who can provide medical records evidencing a relatively serious condition such as congestive heart failure, cancer or Alzheimer’s disease (Rusconi, 2008). In the U.K., substandard annuities are available to individuals with severe medical conditions, as well as to those with milder lifestyle conditions (e.g. high cholesterol, smoking). It is estimated that as many as 40 per cent of U.K. annuity purchasers qualify for underwritten annuities, which accounts for almost 60 per cent of annuity premium in the open market (Becker, 2012).

Importantly, the size of profits depends on the quality of underwriting. Hoermann and Russ (2008) conclude that more extensive risk classification is beneficial for both the insurer and the insured. The practice of individual underwriting for life annuities will always increase the insurer’s profitability, provided the company can correctly appraise the actual mortality distribution in the population.

In March 2011, the European Court of Justice banned the use of sex in insurance pricing across the European Union on grounds of sex discrimination (Reuters, 2011). Britain and other E.U. states have enforced the ban on all new insurance contracts, including annuities, since December 2012.

The focus is on mortality among older adults near retirement since this age group is most representative of prospective annuitants in the wider population.

For example, the overstating smoking or drinking habits in order to get better annuity rates.

Another possible reason why insurers do not use extensive risk classification is cost. Specifically, annuity providers in thin markets may not find the start-up costs for a risk classification system worthwhile (Diamond, 2004; Mackenzie, 2006). A market-based study by Batty et al. (2010) reports that U.S. life insurance providers typically spend an estimated one month and several hundred dollars underwriting each applicant. Property and casualty insurers incur about 26 cents per premium dollar in underwriting expenses (Browne and Kamiya, 2012).

Family history pertaining to certain chronic conditions may also be useful in this context since it is immutable. For example, Wang et al. (2011) find that an individual’s family cancer history contains additional valuable information for underwriting purposes and can thus help mitigate adverse selection in the cancer insurance market.

This factor is also directly relevant to the growing concern in the U.S. about how obesity relates to mortality and morbidity among older adults (SOA, 2010).

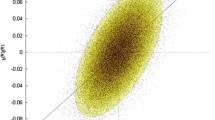

The correlation between father’s and mother’s educations is 0.55 in the present analysis. As in Mirowsky and Ross (2000), if data is missing for one parent, I use the value for the other parent. If data is missing for both parents, I assign the sample mean. See Table A1 in Appendix for summary statistics.

Cognitive scores range from 0 to 40 and are re-scaled to 0–8 for easier interpretation here. The HRS is one of the first national health surveys to measure cognitive health at the population level. Cognitive tests are administered based on well-validated measures developed from psychological research on intelligence and cognition (Herzog and Wallace, 1997). Such tests include immediate and delayed word recall, serial 7s and backwards counting.

While still a subject of current debate, some researchers suggest that cognitive ability or intelligence could even be immutable. For example, Deary (2008) opines that intelligence is “substantially heritable” and tends to be stable across the whole lifespan.

A total of 12,521 age-eligible respondents and their spouses were first interviewed in 1992 (HRS, 2009). Of these, 9,281 are age-eligible (i.e. born between 1931 and 1941, both years inclusive) and non-proxy respondents. A further 234 subjects are dropped due to incomplete information on survival status. See HRS (2008) for a summary of HRS multistage sample design, enrolments, implementation, and response rates.

The abbreviation “ref.” henceforth denotes reference group for the given risk variable.

I use a cohort life expectancy of 65 for fathers and 69 for mothers, estimated based on the remaining life expectancies of a 15-year old and a 30-year old from the sex-specific 1930 and 1940 cohort life tables (sourced from Social Security Administration life tables 1900–2100).

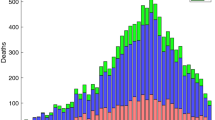

I rely foremost on the death records obtained by HRS through exit interviews with surviving spouses or surviving relatives. Where exit interviews are unavailable or incomplete, NDI information in the Tracker file is used (HRS, 2009). Consequently, of the 1,905 deaths, death data for the majority of cases are obtained from exit interview records, 11.3 per cent (215) from NDI records, and 0.5 per cent (10) imputed based on the wave-by-wave vital status. In the ten imputed cases where vital status is known but the exact death dates are missing, respondents are assumed to have died in the year between the two-year interval where their vital status switched from “alive (or presumed alive)” in one wave to “dead” in the next wave.

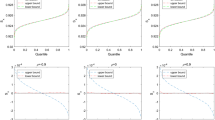

This is not surprising since the human mortality curve is known to display a regular and nearly exponential increase that can be represented by the Gompertz function from age 40 to around age 85 (Preston et al., 2001), and the sampled HRS respondents are aptly within this age range over the observation period. Also, a parametric estimation model is used here instead of the Cox (semi-parametric) model since it generally produces more efficient estimates of the coefficients.

The thresholds defined for these variables are consistent with those used in prior studies, for example, Dupre et al. (2009).

The p-values for the interaction terms are in the range of 0.36–0.57.

A related strand of literature suggests that the vital status of a same-sex parent has a stronger effect on individuals’ subjective life expectancies than that of a different-sex parent. For example, Hurd and McGarry (2002) find that the effect of a mother’s death on self-assessed survival probabilities is significantly larger for females than for males.

The figure of 21.1 per cent (as at Wave 9) includes permanently attrited subjects in the denominator. Tracker file information suggests that the bulk of attriters had requested removal from the HRS survey in-person while alive, so there are few unaccounted deaths among the attriters. The mortality rate is 22.5 per cent if attriters are excluded. HRS (2008) reports that, as at Wave 7, the cumulative mortality for the HRS birth cohort is 15.9 per cent. The 1992 population period life table is sourced from the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics.

To place these estimates in perspective, the instantaneous probability of death for the baseline individual (i.e. female age 50 in 1992) works out to be about 0.001 as at 2008 cut-off and that for a same-age male is about 0.0016 (1.62 × 0.001). In contrast, a much older male aged 60 in 1992 starts with a hazard rate of about 0.0011 in 1992, which increases to almost 0.004 by the time he reaches age 76 in 2008. He faces about 3.84 times higher mortality risk than the baseline female at any given point in time.

The adjusted R 2 measures how much of the variation in outcome in a proportional hazards model is accounted for through the prognostic index (xβ), adjusting for censored observations and the dimension of the model. Age-squared and sex-age interaction terms are not statistically significant (p>0.10) in Model A.

The Wald chi-square statistic (G 2) measures model fit, accounting for the clustering across observations for the same subject. To assess improvement in fit, I calculate the p-value of the difference between the test statistics for Models B1 and A, Models B2 and B1, and Models C and B2. Results indicate that the effects are highly significant (p<0.01) for each successive addition of covariates. The bottom of Table 1 also shows the estimated g parameter for each model; positive g is consistent with monotonically increasing Gompertz hazard functions.

The magnitudes of hazard ratio estimates in this analysis are broadly consistent with those presented in earlier studies using HRS data. For example, using a Cox proportional mortality hazards model and a sample of HRS male respondents, Sloan et al. (2010) report hazard ratios of 0.945 for high school education, 0.794 for married, 1.170 for blacks, 1.006 for baseline age and 0.83 for foreign-born.

Also using HRS data, Mehta and Chang (2009) find hazard ratios below unity for overweight (p<0.05) and Class I obese (30⩽ BMI<35) but hazard ratios above unity for Class II/III obese (BMI⩾35). They conclude that obesity is not a significant cause of mortality in the HRS population because few individuals are extremely obese. Segregating among obesity types, I derive similar results in the present analysis: being Class III obese has a hazard ratio above one, but the effect is not significant (results not presented in detail).

This observation is consistent with the finding in Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2008) that the better educated tend to exhibit healthier behaviours; in particular, those with more years of schooling are less likely to smoke. The diminished effect of BMI on mortality (moving from Model B2 to Model C) is also due to the inclusion of smoking. The bivariate correlation between smoking and education is −0.12 and that between smoking and BMI is −0.08.

For example, Rodgers et al. (2003) find that cognitive ability differs by race and ethnicity in a nationally representative sample of U.S. older adults. Being non-white (African-American or Hispanic) is significantly associated with lower total cognitive scores. Furthermore, a larger negative relationship is noted for African-American than Hispanic.

This ranking by forward selection is broadly consistent with that from a backward selection procedure, except that the latter ranks BMI and cancer more highly. The backward selection based on partial Rs (see e.g. Idler and Angel, 1990) is less preferred as it is sensitive to the composition of the initial list of variables. Adding the eight best-ranked factors here (out of the 16) to age and sex achieves an adjusted R 2 of 27.8 per cent (SE=0.0136).

The average 30-year Treasury bond yield from 1988 to 2010 is 6.3 per cent (available at www.federalreserve.gov). Because the yield has been falling in recent years (4.25 per cent as at end 2010), an alternative rate of 4 per cent is used in the valuations. It is assumed that the insurer always earns exactly this rate on the assets backing the annuity and so, any profit or loss stems solely from annuity pricing simulations and not from reinvestment risk.

Brown (2003) shows this holds for utility-based valuations, in addition to financial valuations. Note also that the zero-loads assumption is typical in previous studies performing annuity equivalent wealth calculations: individuals are assumed to have access to an actuarially fair annuity market in one scenario, and no access to the annuity market in a counterfactual scenario (e.g. Mitchell et al., 1999).

For example Cheung et al. (2005).

Please refer to Table A1 in the Appendix for summary statistics. The prevalence of cognitive ability categories among the female sample is as follows: 71 per cent have average cognition (mean score ± 1 SD=1.60–3.75, inclusive), 13 per cent have below-average cognition (0<score<1.60), and 16 per cent have below-average cognition (3.75<score<8).

Other factors also triggering large-scale participation in annuity markets may include the retirement of the baby boomer generation, or market regulation/government policies. In the U.S., some commentators have proposed that annuitisation should be made the default payout mechanism for 401(k) pensions. For instance, John et al. (2008) suggest that 401(k) assets be automatically directed into a “trial” payout product that lasts 24 months, after which the retiree can either do nothing (and continue to receive monthly payouts) or elect an alternative distribution option. In the U.K., large-scale participation in annuity markets has stemmed from a long history of compulsory annuitisation for workers holding private defined contribution pension accounts. Singapore also recently rolled out mandatory annuitisation of retirement assets under its national defined contribution scheme (Fong et al., 2011).

To further check robustness, I assume a setting where the buyers’ average risk is greater than the average risk of the population under pricing schemes S2 and S3, and re-compute the MWR values. This setting reflects the “average clientele risk” faced by insurers, which arises when higher-risk individuals purchase more insurance than do lower-risk individuals, thus driving the price above the population-weighted actuarially fair price (Hoy and Polborn, 2000; Hoy and Witt, 2007). Results suggest that the stated conclusions are robust to this simple variation in price effect assumption.

For example, Mitchell et al. (1999), Brown (2001), Dushi and Webb (2004).

In a seminal article, Yaari (1965) incorporates uncertain lifetimes into a standard life cycle consumption model and derive conditions under which full annuitisation was optimal. The stylised result of the Yaari model is that consumers with no bequest motives will fully annuitise their wealth. Davidoff et al. (2005) show that, with complete markets, this full annuitisation result will still hold in a more general set of circumstances.

Although life cycle models suggest that annuities are a theoretically appealing way to manage longevity risk, in the real world, relatively few retirees voluntarily annuitise any wealth. Some of the key explanations put forward for this “annuity puzzle” include adverse selection; bequest motives; precautionary savings and the need for liquidity; pre-annuitised wealth in Social Security; risk-pooling within families; and financial illiteracy (see, e.g. Brown et al., 2001, Lockwood, 2012).

This is consistent with previous simulation work, which has considered cases where 0, 50, or 75 per cent wealth is pre-annuitised (see e.g. Mitchell et al., 1999; Dushi and Webb, 2004). In particular, the case in which 50 per cent wealth is pre-annuitised is consistent with Brown’s (2001) observation that about half of the average U.S. household’s wealth at retirement is held in Social Security and defined benefit pensions combined.

For instance, Mitchell et al. (1999) conclude that a 65-year-old male with log utility will find access to annuitisation equivalent to roughly a 50 per cent increase in non-annuitised wealth. Brown (2003) reports AEW values ranging from 1.472 to 1.570 for 67-year-old individuals with a risk aversion parameter of three, and under an age-only pricing scheme.

Dispersion refers to the absolute difference in annuity values between the “very long-lived” group and the “very short-lived” group (which represents two ends of the longevity spectrum). The AEW is a dollar measure of how much value a life cycle individual places on access to annuity markets and is thus comparable with the MWR metric, which is also a dollar measure (financial returns per dollar premium invested).

References

Banking Times. (2008) ‘NU Increases Risk Factors in Annuity Pricing’, from www.bankingtimes.co.uk/17062008-nu-increases-risk-factors-in-annuity-pricing, accessed 1 December 2013.

Batty, M., Tripathi, A., Kroll, A., Wu, C., Moore, D., Stehno, C., Lau, L., Guszcza, J. and Katcher, M. (2010) Predictive Modeling for Life Insurance, Deloitte Consulting LLP.

Becker, G. (2012) ‘Around the World—UK Underwritten Annuities’, from www.covermagazine.co.uk/cover/feature/2217200/around-the-world-uk-underwritten-annuities, accessed 1 December 2013.

Bestwire. (2010) ‘Towers Watson Finds Growth in U.K. Enhanced Annuity Market’, www3.ambest.com/ambv/bestnews/newscontent.aspx?refnum=141014&AltSrc=27, accessed 1 December 2013.

Brown, J.R. (2003) ‘Redistribution and insurance: Mandatory annuitization with mortality heterogeneity’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 70 (1): 17–41.

Brown, J.R. (2001) ‘Private pensions, mortality risk, and the decision to annuitize’, Journal of Public Economics 82 (1): 29–62.

Brown, J.R., Mitchell, O.S., Poterba, J.M. and Warshawsky, M.J. (2001) The Role of Annuity Markets in Financing Retirement, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Brown, R.L. and McDaid, J. (2003) ‘Factors Affecting Retirement Mortality’, North American Actuarial Journal 7 (2): 24–43.

Browne, M.J. and Kamiya, S. (2012) ‘A theory of the demand for underwriting’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 79 (2): 335–349.

Cheung, S.K., Rabine, J., Tu, E.J. and Caselli, G. (2005) ‘Three dimensions of the survival curve: Horizontalization, verticalization, and longevity extension’, Demography 42 (2): 243–258.

Congressional Budget Office, CBO. (1998) Social Security Privatization and the Annuities Market, Washington DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Crocker, K.J. and Snow, A. (1986) ‘The efficiency effects of categorical discrimination in the insurance industry’, The Journal of Political Economy 94 (2): 321–344.

Cutler, D. and Lleras-Muney, A. (2008) ‘Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence’, in J. House, R. Schoeni, G. Kaplan and H. Pollack (eds.), Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as Health Policy, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Davidoff, T., Brown, J.R. and Diamond, P.A. (2005) ‘Annuities and individual welfare’, American Economic Review 95 (5): 1573–1590.

Deary, I.J. (2008) ‘Why do intelligent people live longer’? Nature 456 (7219): 175–176.

Deaton, A. and Paxson, C. (2001) ‘Mortality, education, income and inequality among american cohorts’, in D. Wise (ed.), Themes in the Economics of Aging, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, pp. 129–170.

Delavande, A. and Rohwedder, S. (2011) ‘Differential survival in Europe and the United States: Estimates based on subjective probabilities of survival’, Demography 48 (4): 1377–1400.

Diamond, P. (2004) ‘Social security’, The American Economic Review 94 (1): 1–24.

Dupre, M.E., Beck, A.N. and Meadows, S.O. (2009) ‘Marital trajectories and mortality among US adults’, American Journal of Epidemiology 170 (5): 546–555.

Dushi, I. and Webb, A. (2004) ‘Household annuitization decisions: Simulations and empirical analyses’, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 3 (2): 109–143.

Finkelstein, A., Poterba, J. and Rothschild, C. (2009) ‘Redistribution by insurance market regulation: Analyzing a ban on gender-based retirement annuities’, Journal of Financial Economics 91 (1): 38–58.

Finkelstein, A. and Poterba, J. (2006) Testing for adverse selection with ‘unused observables’, National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 12112, U.S.A.

Fong, J.H., Mitchell, O.S. and Koh, B.S. (2011) ‘Longevity risk management in Singapore’s national pension system’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 78 (4): 961–981.

Hauser, R.M. and Palloni, A. (2010) Why intelligent people live longer, Working Paper No. 2010–04, Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Health and Retirement Study, HRS. (2008) Sample sizes and response rates (2002 and beyond), HRS Survey Design Documents, University of Michigan.

Health and Retirement Study, HRS. (2009) Data description and usage: HRS Tracker 2008 (v1.0), HRS User Guides, University of Michigan, December.

Herzog, A.R. and Wallace, R.B. (1997) ‘Measures of cognitive functioning in the AHEAD study’, Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 52B (Special Issue): 37–48.

Hoermann, G. and Russ, J. (2008) ‘Enhanced annuities and the impact of individual underwriting on an insurer’s profit situation’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 43 (1): 150–157.

Hoy, M. (2006) ‘Risk classification and social welfare’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance: Issues and Practice 31 (2): 245–269.

Hoy, M. and Lambert, P. (2000) ‘Genetic screening and price discrimination in insurance markets’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance: Issues and Practice 25 (2): 103–130.

Hoy, M. and Polborn, M. (2000) ‘The value of genetic information in the life insurance market’, Journal of Public Economics 78 (3): 235–252.

Hoy, M. and Witt, J. (2007) ‘Welfare effects of banning genetic information in the life insurance market: The case of BRCA1/2 genes’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 74 (3): 523–546.

Hurd, M.D. and McGarry, K. (2002) ‘The predictive validity of subjective probabilities of survival’, Economic Journal 112 (482): 966–985.

Idler, E.L. and Angel, R.J. (1990) ‘Self-Rated health and mortality in the NHANES-1 epidemiologic follow-up study’, American Journal of Public Health 80 (4): 446–452.

James, E. and Song, X. (2004) Annuities markets around the world: Money’s worth and risk intermediation, SSRN working paper, Social Science Research Network, Chicago, IL.

John, D.C., Iwry, J.M., Walker, L. and Gale, W.G. (2008) Increasing Annuitization of 401(k) Plans with Automatic Trial Income, Policy Brief 2008-02 Washington DC: Brookings Institution.

Kwon, H. and Jones, B. (2006) ‘The impact of the determinants of mortality on life insurance and annuities’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 38 (2): 271–288.

Lockwood, L. (2012) ‘Bequest motives and the annuity puzzle’, Review of Economic Dynamics 15 (2): 226–243.

Mackenzie, G.A. (2006) Annuity Markets and Pension Reform, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mehta, K.M., Yaffe, K., Langa, K., Sands, L., Whooley, M. and Covinsky, K. (2003) ‘Additive effects of cognitive function and depressive symptoms on mortality in older community living adults’, The Journals of Gerontology: Medical Sciences 58 A (5): M461–467.

Mehta, N.K. and Chang, V.W. (2009) ‘Mortality attributable to obesity among middle-aged adults in the United States’, Demography 46 (4): 851–872.

Mirowsky, J. and Ross, C.E. (2000) ‘Socioeconomic status and subjective life expectancy’, Social Psychology Quarterly 63 (2): 133–151.

Mitchell, O.S., Poterba, J., Warshawsky, M. and Brown, J.R. (1999) ‘New evidence on the money’s worth of individual annuities’, American Economic Review 89 (5): 1299–1318.

Popham, F. and Mitchell, R. (2007) ‘Self-rated life expectancy and lifetime socio-economic position: Cross-sectional analysis of the British household panel survey’, International Journal of Epidemiology 36 (1): 58–65.

Preston, S.H., Elo, I.T., Rosenwaike, I. and Hill, M. (1996) ‘African-American mortality at older ages: Results of a matching study’, Demography 33 (2): 193–209.

Preston, S.H., Heuveline, P. and Guillot, M. (2001) Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes, Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Reuters. (2011) ‘UK to apply EU Insurance Gender Rule from end 2012’, www.reuters.com/article/2011/06/30/idUKL6E7HU13W20110630?type=companyNews, accessed 1 December 2013.

Ridsdale, B. (2012) Annuity underwriting in the United Kingdom, working paper, International Actuarial Association Mortality Working Group.

Rodgers, W.L., Ofstedal, M.B. and Herzog, A.R. (2003) ‘Trends in scores on tests of cognitive ability in the elderly US population, 1993–2000’, The Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 58B (6): S338–S346.

Rothschild, C. (2011) ‘The efficiency of categorical discrimination in insurance markets’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 78 (2): 267–285.

Rusconi, R. (2008) National annuity markets: Features and implications, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development working papers on Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 24, Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs, France.

Singh, G.K. and Siahpush, M. (2001) ‘All-cause and cause-specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States’, American Journal of Public Health 91 (3): 392–399.

Sloan, F.A., Ayyagari, P., Salm, M. and Grossman, D. (2010) ‘The longevity gap between black and white men in the united states at the beginning and end of the 20th century’, American Journal of Public Health 100 (2): 357–363.

Society of Actuaries, SOA. (2010) Obesity and its relation to mortality and morbidity costs, Society of Actuaries Research Projects Series working paper, Committee on Life Insurance Research, U.S.A.

Sorlie, P., Rogot, E., Anderson, R., Johnson, N.J. and Backlund, E. (1992) ‘Black-white mortality differences by family income’, The Lancet 340 (8815): 346–350.

Stewart, F. (2007) Policy issues for developing annuities markets, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development working papers on Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 2, Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs, France.

Towers, W. (2013) Enhanced annuity sales eclipse the £4 billion barrier, press release (18 February).

Wang, K.C., Peng, J.L., Sun, Y.Y. and Chang, Y.C. (2011) ‘The asymmetric information problem in Taiwan’s cancer insurance market’, The Geneva Risk and Insurance Review 36 (2): 202–219.

Yaari, M.E. (1965) ‘Uncertain lifetime, life insurance, and the theory of the consumer’, Review of Economic Studies 32 (2): 137–150.

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted to the Editor (Michael Hoy) and two anonymous referees for useful comments, which helped improve the manuscript significantly. The author would like to thank Jeffery Brown, Irma Elo, Dean Foster, Benedict Koh, Jean Lemaire, Olivia Mitchell, Greg Nini, Samuel Preston, Kent Smetters, Jeremy Tobacman and Tony Webb for helpful discussions on an earlier version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fong, J. Beyond Age and Sex: Enhancing Annuity Pricing. Geneva Risk Insur Rev 40, 133–170 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/grir.2014.12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/grir.2014.12