Abstract

This paper uses a global input-output framework to quantify U.S. and European Union (EU) demand spillovers and the elasticity of world trade to GDP during the global recession of 2008–09. Cross-border intermediate goods linkages have implications for the transmission of shocks and the relationship between demand, trade, and production across countries. This paper finds that 20–30 percent of the decline in U.S. and EU final demand was borne by foreign countries, with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and emerging Europe hit hardest. Allowing final demand to change in all countries simultaneously, the framework presented here delivers an elasticity of world trade to GDP of 2.8. Thus, demand forces alone can account for roughly 70 percent of the trade collapse. Large changes in demand for durables play an important role in driving these results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Among the 57 countries covered by the IMF's Global Data Set (GDS) database, 53 suffered declines in output in these two quarters. Only China, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan had higher real GDP in 2009:Q1 than in 2008:Q3 (Source: IMF-GDS). For analysis of a broad set of trade issues related to crisis, see Baldwin (2009) and Baldwin and Evenett (2009).

Source: IMF-GDS.

See Hummels, Ishii, and Yi (2001), Miroudot and Ragoussis (2009), or Amador and Cabral (2009) for evidence on rising vertical specialization.

We do not address many other implications of intermediate goods trade. For example, we do not address how de-fragmentation of international production chains in response to shocks or increased trading frictions could lower trade. Thus, the mechanism highlighted by Yi (2003) is not covered in this paper. In addition, we do not study how low elasticities of substitution across stages in a production chain might amplify shock transmission, a point that has been emphasized by Burstein, Kurz, and Tesar (2008).

Related frameworks have been developed by Trefler and Zhu (2005) to study the factor content of trade and Daudin, Rifflart, and Schweisguth (2009) and Wang, Powers, and Wei (2009) to study regionalization of trade patterns.

Because we use national accounts definitions in classifying intermediates and final goods in constructing this table, the data can be matched to standard macroeconomic data.

We compute the response of trade and production to realized U.S. and European demand changes, not identified idiosyncratic shocks. Realized changes combine the effect of exogenous shocks and the endogenous propagation of those shocks, which we do not model explicitly.

Borchert and Mattoo (2009) note that declines in services trade have been comparatively small.

See Evenett (2009) on measured trade barriers, or Eaton and others (2010) and Jacks, Meissner, and Novy (2009) on gravity-based estimates of trade barriers. Alessandria, Kaboski, and Midrigan (2010) demonstrate the importance of inventories in propagating demand shocks. See Amiti and Weinstein (2009), Iacovone and Zavacka (2009), and Chor and Manova (2009) on credit frictions.

The main point of similarity is that both papers feed data-based demand changes through a model, and both papers find a strong role for this force. The procedures for computing demand changes differ, however.

For example, if aggregate final demand falls by 1 percent, then domestic demand and import demand both fall by 1 percent, and import demand falls by the same percentage across all source countries. Similarly, if output falls by 1 percent, input purchases fall by 1 percent for all sector and country sources. To relax these assumption we would need data on consumption and input use changes broken down by origin of the goods, which is not generally available.

Because we have input-output data only for the base period, we are constrained to initial period prices and share data.

Further, note that if there is a 1 percent disturbance to country 1's demand alone (q1c=1 and qcj≠1=0), then country 1's output declines by only fraction s11, with the remainder of the fall in demand hitting the other two countries.

A blog post by O’Rourke (2009) with a simple numerical example is typically cited as the genesis of this idea, though it was percolating various places at the time. This point has been picked up and advanced by others, including Benassy-Quere, Decreux, Fontagne, and Khoudour-Casteras (2009) and Altomonte and Ottaviano (2009).

See Freund (2009), Cheung and Guichard (2009), and Irwin (2002).

These data are compiled based on several sources, including World Bank and IMF macroeconomic and Balance of Payments statistics, United Nations Comtrade and OECD Services trade databases, and input-output tables from national statistical sources. To reconcile data from these different sources, GTAP researchers adjust individual countries input-output tables to be consistent with international data sources. See Narayanan and Walmsley, 2008.

Composite regions are composed of countries for which GTAP does not have individual input-output tables. GTAP assigns these regions “representative” input-output tables, constructed as linear combinations of input-output tables of similar countries.

As a consequence, the level of value added is distorted relative to the national accounts. Whereas the national accounts measure value added as the value of output at basic prices minus the value of intermediate inputs at the purchaser's price, we calculate value added as the value of output at basic prices minus the value of intermediate inputs at basic prices.

Durables are defined as sectors 38–42 in GTAP 7 data and broadly include machinery and equipment. Nondurables are defined as sectors 15–37 and 43–45 and include all other industrial production and utilities. All other sectors, that is, 1–14 and 46–57, are included in services.

EU: All EU, except countries that have joined since 2004. Emerging Europe: Czech Rep., Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovak Rep., Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Turkey. Emerging Asia: Hong Kong, Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Singapore. South America: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela. NAFTA: Mexico and Canada.

Comparable results for the EU15, Japan, and China are reported in Appendix B of the companion working paper (Bems, Johnson, and Yi, 2010). Results for the EU15 are qualitatively and quantitatively similar to results for the United States, with Emerging Europe replacing NAFTA as the trading partner with the largest exposure.

To re-normalize shocks so as to generate equal changes in total demand, one can divide the shock by the share of the sector in total demand. Dashes in the table indicate entries that are zero by construction of the exercise.

In particular, the distribution of weights for final imports across services, nondurables and durables is: 0.11, 0.34, and 0.55, and for intermediate imports the weights are correspondingly 0.21, 0.50, and 0.30.

Because U.S. services output is very sensitive to domestic demand changes in the service sector (SUS, US (services, services)≈1), and the service sector has a larger weight in intermediate imports

the elasticity of intermediate imports is higher than the elasticity of final imports in response to services demand changes. In contrast, output for durables is less sensitive to changes in domestic demand and intermediate imports by the durables sector constitute a smaller share of total intermediate imports, so the ranking is reversed for durables.

the elasticity of intermediate imports is higher than the elasticity of final imports in response to services demand changes. In contrast, output for durables is less sensitive to changes in domestic demand and intermediate imports by the durables sector constitute a smaller share of total intermediate imports, so the ranking is reversed for durables.We obtain durables demand data from a mix of OECD and national sources. For the United States and EU15 we use data from the BEA and Eurostat. Because these durables expenditure data are missing for many emerging markets and smaller OECD countries, we make additional assumptions where necessary. If durables production data are available, we use these data for guidance. Alternatively, where no data are available (for example, for China) we assume that demand declines symmetrically across durables and nondurables (see Appendix II for details).

This is the period with the largest decrease in global demand. Further, in looking at Q1–Q1 changes, we can ignore seasonal adjustments.

For example, aggregate demand change in the United States is derived as (−31.6) × 0.10+(−2.2) × 0.11+(−1.3) × 0.79=−4.4, and the response of gross exports in the United States is derived as (−31.6) × 0.15+(−2.2) × 0.12+(−1.3) × 0.03=−1.7. In the same way, using only results in Table 2, one can derive any other response of interest.

China exports approximately 60 percent more goods to the United States than Japan in our data. In 2004, the base year in our data, China exported about $211 billion of goods to the United States, while Japan exported $133 billion.

With the disaggregation of the EU15 composite, we now count intra-EU trade in our world trade aggregates and in the table report changes in trade for the EU including both extra-EU and intra-EU trade.

Note that we do not disaggregate durables and nondurables demand for China owing to lack of data. This assumption almost surely biases our global elasticity estimates downward.

Further details about the fit of the I-O model results with data at the level of 55 countries are provided in Appendix 4 of the working paper version of this paper (Bems, Johnson, and Yi, 2010).

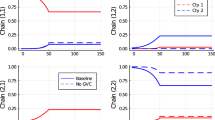

Changes in total demand are taken directly from the data and are the same across specifications. Thus, the only difference across panels is the extent to which we restrict demand changes to be symmetric across sectors.

This elasiticity is even lower for EU15-only demand changes, estimated at 1.5 (see Appendix B in Bems, Johnson, and Yi, 2010).

We do not use consumer expenditures on durables, as about 50 percent of such expenditures are spent on trade and transportation services. For investment expenditures, such services account for less than 10 percent of expenditures (see Bems, 2008).

References

Alessandria, G., J. Kaboski, and V. Midrigan, 2010, “The Great Trade Collapse of 2008–09: An Inventory Adjustment?” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 254–294.

Altomonte, C., and G.I. Ottaviano, 2009, “Resilient to the Crisis? Global Supply Chains and Trade Flows,” in The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences, and Prospects, ed. by R. Baldwin, Chapter 11, pp. 95–100, VoxEU.org.

Amador, J., and S. Cabral, 2009, “Vertical Specialization across the World: A Relative Measure,” North American Journal of Economics and Finance, Vol. 20, pp. 267–280.

Amiti, M., and D. Weinstein, 2009, Exports and Financial Shocks, NBER Working Paper 15556.

Baldwin, R., ed. 2009, “The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences and Prospects”, VoxEU.org.

Baldwin, R., and S. Evenett, eds. 2009, “The Collapse of Global Trade, Murky Protectionism, and the Crisis”, VoxEU.org.

Behrens, K., G. Corcos, and G. Mion, 2010, Trade Crisis? What Trade Crisis? Unpublished Manuscript, Universite du Quebec a Montreal.

Bems, R., 2008, “Aggregate Investment Expenditures on Tradable and Nontradable Goods,” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 852–883.

Bems, R., R.C. Johnson, and K.-M. Yi, 2010, Demand Spillovers and the Collapse of Trade in the Global Recession, IMF Working Paper No. 10/142.

Benassy-Quere, A., Y. Decreux, L. Fontagne, and D. Khoudour-Casteras, 2009, Economic Crisis and Global Supply Chains, CEPII Document de Travail, No. 2009-15 (July).

Blanchard, O., H. Faruqee, and M. Das, 2010, The Initial Impact of the Crisis on Emerging Market Countries, Unpublished Manuscript, International Monetary Fund.

Borchert, I., and A. Mattoo, 2009, “Services Trade—The Collapse that Wasn’t,” in The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences, and Prospects, ed. by R. Baldwin, VoxEU.org.

Burstein, A., C. Kurz, and L. Tesar, 2008, “Trade, Production Sharing, and the International Transmission of Business Cycles,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 55, pp. 775–795.

Cheung, C., and S. Guichard, 2009, Understanding the World Trade Collapse, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 729.

Chor, D., and K. Manova, 2009, Off the Cliff and Back: Credit Conditions and International Trade during the Global Financial Crisis, Unpublished Manuscript, Stanford University.

Daudin, G., C. Rifflart, and D. Schweisguth, 2009, Who Produces for Whom in the World Economy? OFCE Document de travail, No. 2009–18.

DiGiovanni, J., and A. Levchenko, 2010, “Putting the Parts Together: Trade, Vertical Linkages, and Business Cycle Comovement,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 2, pp. 95–124.

Eaton, J., S. Kortum, B. Neiman, and J. Romalis, 2010, Trade and the Great Recession, Unpublished Manuscript, University of Chicago.

Engel, C., and J. Wang, 2009, International Trade in Durable Goods: Understanding Volatility, Cyclicality, and Elasticities, Unpublished Manuscript, University of Wisconsin.

Evenett, S., 2009, “Crisis-era Protectionism One Year after the Washington G20 Meeting: A GTA Update, Some New Analysis, and a Few Words of Caution,” in The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences, and Prospects, ed. by R. Baldwin, VoxEU.org, London, CEPR.

Freund, C., 2009, The Trade Response to Global Downturns: Historical Evidence, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5015.

Hummels, D., J. Ishii, and K.-M. Yi, 2001, “The Nature and Growth of Vertical Specialization in World Trade,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 54, pp. 75–96.

Iacovone, L., and V. Zavacka, 2009, Banking Crises and Exports: Lessons from the Past, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5016.

Imbs, J., 2010, “The First Global Recession in Decades,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 327–354.

Irwin, D.A., 2002, “Long-run Trends in World Trade and Income,” World Trade Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 89–100.

Jacks, D., C. Meissner, and D. Novy, 2009, “The Role of Trade Costs in the Great Trade Collapse,” in The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences, and Prospects, ed. by R. Baldwin, VoxEU.org.

Johnson, R.C., and G. Noguera, 2009, Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and Trade in Value Added, Unpublished Manuscript, Dartmouth College.

Lane, P., and G.M. Milesi-Ferretti, 2010, “The Cross-country Incidence of the Global Crisis,” doi: 10.1057/imfer.2010.12.

Levchenko, A., L. Lewis, and L. Tesar, 2010, “The Collapse of International Trade during the 2008–2009 Crisis: In Search of the Smoking Gun,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 214–253.

Miroudot, S., and A. Ragoussis, 2009, Vertical Trade, Trade Costs and FDI, OECD Trade Policy Working Paper No. 89.

Narayanan, B., and T. Walmsley, eds. 2008, Global Trade, Assistance, and Production: The GTAP 7 Data Base (Center for Global Trade Analysis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana).

O'Rourke, K., 2009, Collapsing Trade in a Barbie World, www.irisheconomy.ie/index.php/2009/06/18/collapsing-trade-in-abarbie-world.

Trefler, D., and S.C. Zhu, 2005, “The Structure of Factor Content Predictions,” NBER Working Papers 11221.

Wang, J., 2010, “Durable Goods and the Collapse of Global Trade,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Economic Letter (Vol. 5, No. 2).

Wang, Z., W. Powers, and S.-J. Wei, 2009, “Value Chains in East Asian Production Networks—An International Input-output Model Based Analysis,” USTIC Working Paper No. 2009-10-C.

Yi, K.-M., 2003, “Can Vertical Specialization Explain the Growth of World Trade?” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 111, No. 1, pp. 52–102.

Additional information

*Rudolfs Bems is an Economist at the Research Department of the International Monetary Fund since 2006; Kei-Mu Yi is Senior Vice President and Director of the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Robert C. Johnson is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Dartmouth College. This article is based on a previous draft of this paper entitled “The Role of Vertical Linkages in the Propagation of the Great Downturn of 2008.” An IMF Working Paper version was published in 2010. The authors thank Julian Di Giovanni, Elhanan Helpman, participants at the IMF/Banque de Paris/PSE Conference on Economic Linkages, Spillovers, and the Financial Crisis, Harvard University, the editors, and two anonymous referees for comments.

Appendices

Appendix I

Interpreting the Share Weighting Matrix

This appendix discusses the derivation and interpretation of the equation linking output to demand changes: Equation (4) in the text. Stacking and manipulating Equation (3), we can write:

where [diag(y)] is an (SN × SN) matrix with elements y i (s) along the diagonal, q̂ i is a vector of proportional changes in output within each sector in country i, and q̂ i d is a vector of sector-level demand changes in country i. The A matrix is the global input-output matrix with elements A ij (s, t) that record the cost share of intermediate goods from sector s in country i used in production in sector t in country j. It takes the form:

The share matrix is then defined as:

To interpret this matrix, we define d j as the (SN × 1) vector of final goods absorbed in country j. Then [I−A]−1d j is the (SN × 1) vector of output used either directly or indirectly to produce final goods absorbed in country j.

To interpret this expression, [I−A]−1 is the Leontief inverse of the global input-output matrix. The Leontief inverse can be expressed as a geometric series:  Multiplying by the consumption vector, the zero-order term d

j

is the direct output absorbed as consumption, the first-order term [I+A]d

j

is the direct output plus the intermediates used to produce that output, the second-order term [I+A+A2]d

j

includes the additional intermediates used to produce the first round of intermediates (Ad

j

), and the sequence continues as such. Therefore, [I−A]−1d

j

is the vector of output used both directly and indirectly to produce final goods absorbed in country j. Then the output vector can be written as: y = ∑

j

[I − A]−1d

j

. This defines a decomposition of output decomposition according to where that output is embedded in final demand.

Multiplying by the consumption vector, the zero-order term d

j

is the direct output absorbed as consumption, the first-order term [I+A]d

j

is the direct output plus the intermediates used to produce that output, the second-order term [I+A+A2]d

j

includes the additional intermediates used to produce the first round of intermediates (Ad

j

), and the sequence continues as such. Therefore, [I−A]−1d

j

is the vector of output used both directly and indirectly to produce final goods absorbed in country j. Then the output vector can be written as: y = ∑

j

[I − A]−1d

j

. This defines a decomposition of output decomposition according to where that output is embedded in final demand.

The share matrix defined in Equation (4) then computes the shares associated with this output decomposition and arranges them appropriately to premultiply the vector of demand changes.

Appendix II

Estimating Changes in Sectoral Demand

This appendix explains the procedure used to decompose observed changes in total demand into sector-specific demand changes for durable goods, nondurable goods, and services.

To outline the approach, we formulate the problem as one of estimating post-crisis levels of sectoral demand, d̃i,t+1(services), d̃i,t+1(nondurables) and d̃i,t+1(durables), with t+1=2009Q1, subject to the constraint that they add up to the observed total demand in each country. Taking initial pre-crisis levels of sectoral demand (d it (s)) from the model, we can compute post-crisis levels as d̃i,t+1(s)=(1+q̂ i d(s))d it (s), where q̂ i d(s) is obtained from available data using the procedure below. For convenience, we drop the country i subscript below.

In the first step, we take realized proportional changes in total domestic demand, q̂d, from IMF Global Data Source, which contains quarterly, local currency, constant price data for 55 countries. For the EU15 composite, we retrieve total demand data from Eurostat. The post-crisis level of aggregate demand can then be computed as:

Then to split dt+1, we note that the value of output in sector s in the pre-crisis period (t=2008Q1) can be written as:

where gdp denotes the level of GDP, d denotes the level of domestic demand (including inventory changes), nx denotes the level of net trade. We use this identity to split post-crisis demand levels for goods, d̃t+1(nondurables)+d̃t+1(durables), and services, d̃t+1(services) using a sequential procedure:

where  is proportional change in GDP and

is proportional change in GDP and  is the proportional change in the index of industrial production for each country, both obtained from IMF Global Data Source. This procedure assumes that the service sector trade balance did not change during the crisis. Further, it assumes that proportional changes in GDP for non-service sectors are equal to proportional changes in industrial production.

is the proportional change in the index of industrial production for each country, both obtained from IMF Global Data Source. This procedure assumes that the service sector trade balance did not change during the crisis. Further, it assumes that proportional changes in GDP for non-service sectors are equal to proportional changes in industrial production.

Finally, the estimated post-crisis level of domestic demand for goods needs to be separated into d̃t+1(nondurables) and d̃t+1(durables). To do this, we turn to data on durables demand changes to back out the demand for non-durables that is consistent with changes in aggregate demand. Formally:

As detailed expenditure data separating durables and nondurables is not available for all countries, we combine several types of data to approximate q̂d(durables). For the United States and EU15, we use data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and Eurostat on machinery and equipment investment. For other countries, our preferred series is investment expenditures on machinery and equipment from OECD quarterly national accounts.Footnote 34 For select countries (for example, Chile, U.K.) we prioritize national data sources. Finally, for a few countries (for example, Brazil), we use industrial production data for capital goods and consumer durables to proxy for demand changes. This supply-side data will yield a good estimate of demand changes if we assume that the trade balance for durables was unchanged during the crisis. For one major country, China, we were unable to locate any usable data to perform this durables/nondurables split. We therefore assume that demand changes are symmetric across durables and nondurables sectors in China.

the elasticity of intermediate imports is higher than the elasticity of final imports in response to services demand changes. In contrast, output for durables is less sensitive to changes in domestic demand and intermediate imports by the durables sector constitute a smaller share of total intermediate imports, so the ranking is reversed for durables.

the elasticity of intermediate imports is higher than the elasticity of final imports in response to services demand changes. In contrast, output for durables is less sensitive to changes in domestic demand and intermediate imports by the durables sector constitute a smaller share of total intermediate imports, so the ranking is reversed for durables.