Abstract

This paper revisits the bipolar prescription for exchange rate regime choice and asks two questions: Are the poles of hard pegs and pure floats still safer than the middle? And where to draw the line between safe floats and risky intermediate regimes? Our findings, based on a sample of 50 emerging market economies over 1980–2011, show that macroeconomic and financial vulnerabilities are significantly greater under less flexible exchange rate regimes—including hard pegs—as compared with floats. Although not especially susceptible to banking or currency crises, hard pegs are significantly more prone to growth collapses, suggesting that the security of the hard end of the prescription is largely illusory. Intermediate regimes as a class are the most susceptible to crises, but “managed floats”—a subclass within such regimes—behave much more like pure floats, with significantly lower risks and fewer crises. “Managed floating,” however, is a nebulous concept; a characterization of more crisis-prone regimes suggests no simple dividing line between safe floats and risky intermediate regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although the IMF’s de facto exchange rate regime classification tends to incorporate information on intervention, it involves some subjective judgment. It is also not sufficiently granular in terms of taking into account direction/circumstances of intervention.

Some earlier studies have analyzed macroeconomic or financial vulnerabilities associated with different exchange rate regimes individually. For example, Goldfajn and Valdes (1999) and Ghosh, Ostry, and Tsangarides (2010) look at the extent of real exchange rate misalignment under different exchange rate regimes, while more recently, Angkinand and Willett (2011) and Magud, Reinhart, and Vesperoni (2011) analyze the impact of exchange rate regimes on financial-stability risks.

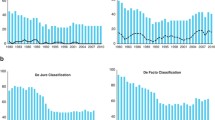

In our sample of EMEs, for example, about 65 percent of de jure pure floats are de facto classified as some type of a managed exchange rate regime (see the online appendix for the list of countries included in the sample).

See Frankel, Schmukler, and Serven (2000), Ghosh, Ostry, and Tsangarides (2010), Klein and Shambaugh (2010), and Rose (2011) for a discussion.

Although monetary policy may be used to influence the exchange rate, the IMF mostly complements information on exchange rate variability with movements in international reserves to form a judgment about a managed rate.

The LYS de facto classification, for example, includes an “inconclusive” category.

The IMF adopted the de facto exchange rate regime classification in 1999, and reported the de jure exchange rate regimes until then. Bubula and Ötker-Robe (2002) and Anderson (2008) harmonize the coverage of the de jure and de facto classifications by extending the former up to 2006, and the latter backwards up to the 1970s.

See IMF (2008) for a detailed description of the methodological revisions to the classification.

Formal statistical tests of the bipolar hypothesis over that period—based on Markov transition matrices—however, reject it as a positive prediction (for example, Masson, 2000; Bubula and Ötker-Robe, 2002). Williamson (2000) also reports most EMEs as “reluctant floaters” in that period, and argues that their desire to manage the exchange rate reflected legitimate concerns about the possible real effects of floating rates.

These broad trends are also apparent using the IMF’s de jure and RR’s classifications (see the online appendix).

That is, countries would never revert to an intermediate regime from a hard peg or pure float (Masson, 2000).

A formal test of stability of the transition matrix for 2000–11 vs. 1980–2011 fails to reject the hypothesis of structural stability (LR test-statistic=4.18, p-value=0.78).

In a recent paper, Chinn and Wei (2013) find that the nominal exchange rate regime does not matter for external adjustment. Several studies, however, question their results on methodological and definitional grounds, and find that less flexible exchange rate regimes are significantly associated with slower external adjustment (for example, Herrmann, 2009; Ghosh, Qureshi, and Tsangarides, 2013).

Backe and Wojcik (2008) highlight another channel through which pegs could fuel domestic credit expansion—for countries with an increasing trend in productivity growth that peg their exchange rate to the currency of an advanced economy (with constant productivity growth), the peg may lead to lower interest rates and higher domestic credit compared with a flexible exchange rate regime.

In countries where the banking sector has borrowed heavily from abroad, a banking crisis is often followed by a currency crisis (Kaminsky and Reinhart, 1999).

Frankel, Schmukler, and Serven (2000), for example, argue that intermediate regimes—mainly basket pegs and bands—inspire less credibility because they are not easily verifiable.

Analyzing vulnerabilities is also useful because crisis observations are coded on the basis of commonly used, yet arbitrary, thresholds of what constitutes a crisis; complementing the analysis with a look at vulnerabilities can therefore yield more robust conclusions. Moreover, identifying vulnerabilities may be a first step to mitigating them, thus making the regime less crisis-prone.

We exclude off-shore financial centers (such as Panama) from the sample in all estimations. Sample size varies across estimations depending on data availability of different variables. See the online appendix for a description of variables and data sources.

We consider positive changes in credit-to-GDP ratio to exclude observations of large credit contractions that tend to be associated with exceptional circumstances (such as crisis cases). Results remain similar if instead of excluding all negative changes, we drop only large outliers (that is, credit contractions in excess of 14 percentage points of GDP, which constitute the bottom fifth percentile of the sample’s distribution).

Dollarized economies are excluded from the sample when computing the share of FX-denominated loans in total bank lending since, by the very nature of the regime, all loans would be classified as FX-denominated.

Ostry and others (2012) explain this result by noting that inflow controls on the banking system will imply fewer FX-liabilities and hence, given open FX-limits, less FX-denominated lending.

Defining currency crisis on the basis of exchange rate movement against the U.S. dollar is unlikely to be problematic in our case since most countries in the sample with managed exchange rates use the U.S. dollar as their base currency. Moreover, in cases where a currency crisis (using the U.S. dollar as the reference currency) is recorded in the data, and the base currency is Deutsche mark/euro or the ruble, sharp depreciations are recorded against the base currency as well.

Results are robust to considering an alternate threshold of the bottom tenth percentile of growth declines, which corresponds to a fall in the growth rate of real GDP of about 4.5 percentage points.

For example, Bulgaria’s currency board arrangement incorporates a prefunded “banking department” as a precaution against banking crises.

The results also remain robust to accounting for economic size by including (log of) total population in the specifications.

Conversely, if there is endogeneity such that countries opt for greater flexibility in anticipation of the crisis, it would tend to downward bias the coefficients on less flexible exchange rate regimes. In this respect, since we mostly find a statistically significant effect of less flexible exchange rate regimes on crisis probability, our estimates could be treated as presenting a lower bound.

This strengthens our results since the finding of an association between less flexible regimes and vulnerabilities is then despite, not because of, potential endogeneity. The statistical significance of the coefficient however disappears once we exclude crisis observations from the regime switches.

As Rogoff and others (2004) note “This problem [endogeneity] cannot be fully resolved but is mitigated by the relatively long duration of the typical regime under the Natural [i.e., de facto] classification, implying that temporary changes in performance do not influence the choice of regime. The problem is also mitigated by using as an explanatory variable the regime prevailing in the previous one or two years ….”

Although the relative ranking of regimes looks similar, the absolute volatility across less flexible regimes tends to be higher under the IMF classification. This may be because the RR classification excludes currency crisis cases, whereas the IMF classification identifies a regime for such cases—including these observations naturally increases the nominal exchange rate volatility. Volatility across regimes is also fairly monotonic under the RR classification—this is likely because they focus more on exchange rate movements in identifying regimes, whereas, as discussed above, the IMF also takes into account other central bank policy actions.

Although several algorithms are available to search for the best split (for example, minimizing the sum of type I and type II errors), we employ the Improved Chi-squared Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID), which uses a chi-squared test to determine the best split (Kass, 1980). Implementation of CHAID is undertaken using the SIPINA classification tree software.

Intervention is defined as I=|ΔR|/(|Δ|+|ΔE|), where ΔR is the annual percentage change in reserves (where change in reserves is measured as reserve flows from the Balance of Payments, rather than change in the stock of reserves, to avoid valuation changes), and ΔE is the annual percentage change in the nominal effective exchange rate (NEER). Results remain essentially similar if the nominal exchange rate against the major anchor currency (such as the U.S. dollar or euro) is used instead. I ranges from zero (no intervention; free float) to one (full intervention; fixed exchange rate). Exchange rate flexibility is defined in terms of monthly NEER volatility—that is, rolling standard deviation of monthly percentage changes in the NEER over 6, 12, or 36 months.

All variables used for classification are lagged one period. The tree correctly classifies about 94 percent of the sample; 29 and 99 percent of the crisis and noncrisis observations, respectively.

This tree is not reported here for brevity but is available upon request.

Although it may be difficult to assess overvaluation in real time, countries could intervene if appreciation pressures do not appear to be driven by changes in domestic fundamentals, or if monetary policy is already supportive (for example, the interest rate is at the zero lower bound).

References

Anderson, H., 2008, “Exchange Policies before Widespread Floating (1945–89),” mimeo (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Angkinand, A. and T. Willett, 2011, “Exchange Rate Regimes and Banking Crises: The Channels of Influence Investigated,” International Journal of Finance and Economics, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 256–274.

Backe, P. and C. Wojcik, 2008, “Credit Booms, Monetary Integration, and the Neoclassical Synthesis,” Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 458–470.

Bubula, A. and I. Ötker-Robe, 2002, “The Evolution of Exchange Rate Regimes since 1990: Evidence from De Facto Policies?” IMF Working Paper 02/155 (Washington, DC: IMF).

Bubula, A. and I. Ötker, 2003, “Are Pegged and Intermediate Regimes More Crisis-prone?” IMF Working Paper 03/223 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Calvo, G. and C. Reinhart, 2002, “Fear of Floating,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117, No. 2, pp. 379–408.

Chinn, M. and S.-J. Wei, 2013, “A Faith-based Initiative Meets the Evidence: Does a Flexible Exchange Rate Regime Really Facilitate Current Account Adjustment?,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 95, No. 1, pp. 168–184.

Dell’Ariccia, G., and others, 2012, “Policies for Macrofinancial Stability: How to Deal with Credit Booms,” IMF Staff Discussion Note 12/06 (Washington DC: International Monetary Fund).

Demirgüç-Kunt, A. and E. Detragiache, 1998, “The Determinants of Banking Crises in Developing and Developed Countries,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 81–109.

Domaç, I. and M. Peria, 2003, “Banking Crises and Exchange Rate Regimes: Is There a Link?,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 41–72.

Eichengreen, B., 1994, International Monetary Arrangements for the 21st Century (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution).

Fischer, S., 1999, “The Financial Crisis in Emerging Markets: Some Lessons.” Speech delivered at the conference of the Economic Strategy Institute, Washington, DC, www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/1999/042899.htm#1 (accessed 4 February 2015).

Fischer, S., 2001, “Exchange Rate Regimes: Is the Bipolar View Correct?,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 3–24.

Fischer, S., 2008, “Mundell-Fleming Lecture: Exchange Rate Systems, Surveillance, and Advice,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 367–383.

Frankel, J., 1999, “No Single Currency Regime is Right for All Countries or at All Times,” NBER Working Paper 7338 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research).

Frankel, J. and A. Rose, 1996, “Currency Crashes in Emerging Markets: An Empirical Treatment,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 41, No. 3–4, pp. 351–366.

Frankel, J., S. Schmukler, and L. Serven, 2000, “Verifiability and the Vanishing Intermediate Exchange Rate Regime,” NBER Working Paper 7901 (Cambridge, MA: NBER).

Freund, C., 2005, “Current Account Adjustment in Industrialized Countries,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 24, No. 8, pp. 1278–1298.

Ghosh, A., A. Gulde, J. Ostry, and H. Wolf, 1997, “Does the Nominal Exchange Rate Regime Matter?,” NBER Working Paper 5874 (Cambridge, MA: NBER).

Ghosh, A., A. Gulde, and Holger Wolf, 2003, Exchange Rate Regimes: Choices and Consequences (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Ghosh, A. et al. 2008, “IMF Support and Crisis Prevention,” IMF Occasional Paper 262 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Ghosh, A., J. Ostry, and C. Tsangarides, 2010, “Exchange Rate Regime and the Stability of the International Monetary System,” IMF Occasional Paper No. 270 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Ghosh, A., M. Qureshi, and C. Tsangarides, 2013, “Is Exchange Rate Regime Really Irrelevant for External Adjustment?,” Economic Letters, Vol. 118, No. 1, pp. 104–109.

Goldfajn, I. and R. Valdes, 1999, “The Aftermath of Appreciations,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 114, No. 1, pp. 229–262.

Herrmann, S., 2009, “Do We Really Know that Flexible Exchange Rates Facilitate Current Account Adjustment? Some New Empirical Evidence for CEE Countries,” Applied Economics Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 4, pp. 295–312.

IMF. 2008, Annual Report on Exchange Rate Arrangements and Exchange Rate Restrictions (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Kaminsky, G. and C. Reinhart, 1999, “The Twin Crises: The Causes of Banking and Balance of Payments Problems,” American Economic Review, Vol. 89, No. 3, pp. 473–500.

Kass, G., 1980, “An Exploratory Technique for Investigating Large Quantities of Categorical Data,” Applied Statistics, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 119–127.

Klein, M. and J. Shambaugh, 2010, Exchange Rate Regimes in the Modern Era (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Laeven, L. and F. Valencia, 2013, “Systemic Banking Crises Database: An Update,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, pp. 225–270.

Levy-Yeyati, E. and F. Sturzenegger, 2005, “Classifying Exchange Rate Regimes: Deeds vs. Words,” European Economic Review, Vol. 49, No. 6, 1603–1635.

Magud, N., C. Reinhart, and E. Vesperoni, 2011, “Capital Inflows, Exchange Rate Flexibility, and Credit Booms,” NBER Working Paper No. 17670 (Cambridge, MA: NBER).

Masson, P., 2000, “Exchange Rate Regime Transitions,” IMF Working Paper 00/134 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Mendoza, E. and M. Terrones, 2008, “An Anatomy of Credit Booms: Evidence from Macro Aggregates and Micro Data,” NBER Working Paper 14049 (Cambridge, MA: NBER).

Montiel, P. and C. Reinhart, 2001, “The Dynamics of Capital Movements to Emerging Economies during the 1990s,” in Short-term Capital Flows and Economic Crises, ed. by S. Griffith-Jones, M. Montes, and A. Nasution (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Ostry, J., A. Ghosh, M. Chamon, and M. Qureshi, 2012, “Tools for Managing Financial Stability Risks,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 88, No. 2, pp 407–421.

Reinhart, C. and K. Rogoff, 2004, “The Modern History of Exchange Rate Arrangements: A Reinterpretation,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 119, No. 1, pp 1–48.

Rogoff, R. et al. 2004, “Evolution and Performance of Exchange Rate Regimes,” IMF Occasional Paper 229 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Rose, A., 2011, “Exchange Rate Regimes in the Modern Era: Fixed, Floating, and Flaky,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 49, No. 3, pp. 652–672.

Rosenberg, C. and M. Tirpák, 2008, “Determinants of Foreign Currency Borrowing in the New Member States of the EU,” IMF Working Paper 08/173 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Shambaugh, J., 2004, “The Effects of Fixed Exchange Rates on Monetary Policy,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 119, No. 1, pp. 301–352.

Tornell, A. and A. Velasco, 2000, “Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rates: Which Provides More Fiscal Discipline?,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 399–436.

Williamson, J., 2000, Exchange Rate Regimes for Emerging Markets: Reviving the Intermediate Option (Washington, DC: Peterson Institute Press).

Acknowledgements

Paper prepared for the IMF’s Fourteenth Annual Research Conference, November 7–8, 2013, Washington, DC. We are grateful to Jeffrey Frankel, Pierre-Olivier Gournichas, anonymous referees, and participants at the IMF’s Annual Research Conference and the 12th Research Meeting of NIPFP-DEA Research Program for very helpful comments and suggestions, and to Hyeon Ji Lee for excellent research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.

Additional information

Supplementary information accompanies this article on the IMF Economic Review website (www.palgrave-journals.com/imfer).

*Atish R. Ghosh is Assistant Director, and Chief, Systemic Issues Division, in the IMF’s Research Department. Prior to joining the IMF, he was an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics and Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs of Princeton University. Jonathan D. Ostry is the Deputy Director of the IMF's Research Department. His areas of responsibility span both research (issues related to the capital account, fiscal and monetary policies, exchange rate regimes and the stability of the international monetary system) and surveillance (including the IMF-FSB Early Warning Exercise and multilateral exchange rate assessments). Mahvash S. Qureshi is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s Research Department. The authors have published widely on international macroeconomic issues.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2015.17.