Abstract

This paper investigates how new discriminatory measures implemented since the start of the global financial crisis are affecting global trade flows. Newly available data on border measures and behind-the-border measures (for example, bailouts and subsidies) implemented through April 2010 are matched to monthly 4-digit bilateral trade data using a first-differenced gravity equation. The estimation strategy exploits within-product variation and utilizes extensive time-varying fixed effects and duad/tetrad ratio estimation to isolate as far as possible the impact of protectionist measures from that of other factors to estimate trade policy impacts. The estimates suggest that trade in country pairs subject to new border measures decreased by 5–8 percent relative to trade in the same product among pairs not subject to new measures. Identification of trade impacts of behind-the-border measures proves to be considerably more challenging, but, also for these measures, evidence points toward a negative impact, possibly of roughly the same magnitude. These results imply a decline in global trade of about 0.2 percent on account of crisis protectionism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some papers address this issue to some extent by disaggregating into individual arrangements currency unions (Eicher and Henn, 2011b) and preferential trade agreements (Eicher, Henn, and Papageorgiou, 2012).

These decompositions of total trade costs, often undertaken through regressions, are again only limited by availability of quantifiable trade cost proxies. For instance, Chen and Novy (2011) analyze the impact of technical barriers to trade in such a framework.

The 2013 WTO report also reports protectionist measures to cover 3.6 percent of world trade at the HS 8-digit level, but refers to a longer period, 2008 to mid-2013, during which more measures have been implemented than captured in our data. The divergence is caused by our trade data being more aggregate (HS 4-digit level), so that more trade is shown to be affected for any measure in our data.

Other sources that have pointed out that protectionism could not have been a significant driver of the global trade collapse include Baldwin and Evenett (2009) and OECD (2010).

Because many of the measures cover only certain subcategories of a 4-digit trade category (our level of analysis), these product-level estimates would probably be larger and more precise if 6-digit or 8-digit trade data were used; however, this bias does not imply that our approximation of aggregate trade impacts, discussed below, is also biased.

See also Henn and McDonald (2011) for further details on these results by income levels and regions.

It is furthermore noteworthy that comparable results emerge, despite the WTO relying on their own monitoring database for data on protectionist measures, instead of GTA. However, a drawback of this study is in our view that no product-specific controls are introduced, though these may be somewhat less important during a noncrisis period when trade growth across products does not vary as dramatically as during 2008–09.

As Germany, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom are EU members, all G20 countries except Saudi Arabia are covered.

For most reporters, the trade flow data extend through either March or April 2010. Exceptions are India (December 2009) and the EU-27, Indonesia, and Mexico (February 2010).

To determine affected trade partners for import policy changes, the GTA team relies as far as possible on information available on the measure directly. If no concrete information on trade partners to which the measure applies can be retrieved in this fashion, GTA reports all trading partners that export one million dollars or more of the product in question to the implementing jurisdiction (based on UN COMTRADE import data for the latest year available before the measure’s implementation).

“Amber” measures are excluded given the uncertainty of their nature. “Green” measures were explored in initial stages of this research but were dropped from the analysis to maintain a close focus on protectionism. We do not believe that this decision introduces much selection bias for several reasons. First, there were relatively few (51) green measures during the sample period with complete data on (i)–(v). Second, like export measures, they normally affected most other trade partners, so are captured in time-varying importer-product fixed effects (in Table 2, specifications 4–6). Finally, the impact coefficients on GTA green measures obtained in our early research were close to zero and statistically insignificant throughout and did not impact any other measures.

Appendix Table A1 in Henn and McDonald (2011) contains detail on each individual measure included and its classification.

The measures implemented during February–May 2010 were those that affected the largest trade flows.

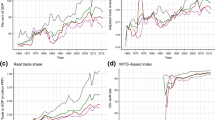

For visual clarity, Figure 1 shows only the (early) implementation months for which the longest time series are available in our database.

The econometric results in Section IV give qualitatively similar results. Table 3, Regression 1 reports most analogous results to the figures presented here. These econometric results are superior to the graphical analysis because the regression’s minimization of squared residuals provides a consistent way of weighing over (i) implementation months and (ii) products affected within each implementation month.

The strong decline at T−2 is driven by measures in one particular implementation month, but nonetheless it cannot be ruled out that an acceleration of declines already began before month T.

In the figures, whether falls in market shares of exporters hit by protectionism are due to the protectionist actions themselves or general collapses of certain country-specific markets cannot be well distinguished, because the market shares of exporters hit by protectionism are calculated relative to the global market in the same product. The regression analysis addresses this.

These figures are included in Henn and McDonald (2011).

This figure is for 2009:Q4, the last period for which trade data are included for all reporters (see footnote 9 “For most reporters, the trade flow data extend…”).

Recent research suggests that the trade collapse of 2008–09 was attributable to three main factors: (i) a sharp decline in the production and trade of durable goods (which account for a much larger share of global trade than of production), (ii) supply chain and inventory adjustment effects, and (iii) somewhat tighter trade finance. See Baldwin (2009); Levchenko, Lewis, and Tesar (2009); and Anderton and Tewolde (2011). Henn and McDonald (2010) and Ahn, Amiti, and Weinstein (2011) provide overviews.

Equation (1) is closely analogous to the specification used in Baier and Bergstrand (2007). See, for example, Anderson and van Wincoop (2003) for a derivation of the gravity equation.

Baier and Bergstrand (2007) highlight that this may induce measurement error bias which could lead to underestimation of protectionist impacts (in absolute terms). However, they judge this type of potential bias much less important in estimating the impact of trade policy variables than omitted variable and simultaneity bias—on which we extensively comment below.

Note that 12-month differencing of fixed effects dummies is not necessary, but interpretation of their coefficients changes as they come to quantify impact of changes in determinants.

This description is correct if the measure has been in place at least for one year before removal, which is the general case in the data. In cases of earlier removal, the differenced protectionist dummy first takes the value of 1 for some months, then the value of 0 for the first months after removal, and the value of −1 for those months one year after those with “1” values.

Restricting this to binary dummies does not have an appreciable effect on the results (see Table 3 in Henn and McDonald, 2011), largely because very few affected country-pair-product observations are subject to more than one protectionist measure. See footnote 49 “Import restrictions, our main variable of interest, break down as follows. Observations affected…”.

With this contribution, Baier and Bergstand started as well a literature on the endogenous formation of Preferential Trade Agreements based on preexisting trade flow patterns. See also Egger and others (2011).

Since Hummels and Levinsohn (1995) first emphasized large unobserved bilateral heterogeneity in gravity equations, a considerable literature has pointed out that gravity estimates may suffer from considerable omitted variable bias if these time-invariant country-pair-specific unobservables are not controlled for via first differencing or country-pair fixed effects (for example, Baldwin and Taglioni, 2006).

To be exact, and as Baier and Bergstrand (2007) point out, these trade flow levels would have to exceed “natural” levels, as predicted by the gravity equation.

The consistency of the estimate for β is unaffected by whether differencing or ijp fixed effects are used as controls for these determinants. However, if serial correlation in the error terms of the gravity equation in levels is likely, as in our case, estimation in differences increases the efficiency of the estimator vis-à-vis country-pair-product fixed effects (Wooldridge, 2002, chapter 10.6; Baier and Bergstrand, 2007).

If these determinants vary considerably over time, time-varying country-pair controls to proxy for γ ijt become important, as included in our specification 3 below. Controlling for these time-varying country-pair-specific influences is only possible in product-level data, because for aggregate trade data the ijt level is the level of individual observations.

In a balanced panel, two fixed effects could be stripped algebraically.

In our estimations, we are mindful that Guimaraes and Portugal’s (2010) methodology can only accommodate two fixed effects at a time. Working around this does not impose a major constraint, however, because two different sets of fixed effects can often be easily combined into a more general one, as is the case for TVCP effects as mentioned below.

The Newey West (1987) and Driscoll Kraay (1998) standard errors were implemented with a 12-month bandwidths for both regressions 1 and 4. Driscoll Kraay (1998) standard errors in addition allow for cross-sectional dependence (across country-pair-product categories). Among the three types of standard errors, the Rodgers (1993) standard errors were the largest in most cases.

Aside from that, there are no available analogues of some variables traditionally used in gravity equations (for example, GDP) at the product level and at monthly frequency, making fixed effects indispensable. In addition, the time-varying country-pair fixed effects used to capture the term Δ12γ ijt are allowed to differ between flows from country i to j and country j to i, because trade policies may vary in the different directions.

Furthermore, controls along the ijt dimension would absorb any changes in bilateral trade costs, which could possibly induce bias. For example, if exchange rate swings or better transport connections lead to higher imports and occurred around the same time as a protectionist action between trade partners, the protectionist coefficient would be biased toward zero.

In devising these summary statistics, we first obtain a ratio of nonzero observations over total observations of the protectionist variable for each importer-product-time combination affected by protectionism. This ratio will always be positive and reaches its maximum value of unity when a measure is uniformly applied to all trade partners. Given that we have such a measure for each importer-product-time combination, we can then evaluate frequency distributions. This distribution has the following mean, first quartile and median for import restrictions respectively: 0.756; 0.667; and 0.800. Behind-the-border measures are considerably more uniformly applied among exporters with analog values here being 0.888; 0.857; and 0.947. Public procurement measures are a subcategory within import restrictions with relatively little variation (0.854; 0.750; 0.917).

There may also be an issue related to the data recording by Global Trade Alert, described in footnote 10 “To determine affected trade partners for import policy changes, the GTA team relies as far as possible….” Their imposition of a threshold for listing affected exporters in some cases may cause measures that are uniformly applied across trade partners to be falsely identified as nonuniform.

Results for regressions that also include export measures are reported in Table 3.

Including TVP fixed effects implies that the estimation of β in Equation (3) relies exclusively on cross-sectional variation. This strategy is similar to that of Amiti and Weinstein (2009), who study the impact of the 1992/93 Japanese banking crisis on Japanese exporters. Their estimation also only uses cross-sectional information at each point in time, comparing whether the performance of exporters in the same sector varied depending on how much their main bank was impacted by the banking crisis.

Note that the protectionist coefficients are semielasticities, because changes in log imports are on the left-hand side of the equation, while the protectionist variables are dummies and not expressed in logs.

In specifications 5 and 6, below, the joint use of importer- and exporter-specific effects is sufficient to control for bilateral exchange rates, because they can be decomposed into exchange rates of importer and exporter relative to a reference currency.

As pointed out above, large declines in imports of a product likely signal a large demand shock affecting this market and also impacting adversely domestic producers of the product.

Effectively, specification 4 is identified only within importer-product-time combinations affected by protectionism, with other observations adding no further information. There are 9,021 of those combinations for import restrictions with 84,727 observations. For behind-the-border measures, there are 3,194 such combinations with 30,882 observations. In specifications 5 and 6, however, the other observations play a role as they help in tying down the coefficient values of the TVEX and TVEXP effects, respectively.

This conclusion assumes that, relative to the world market in the given product, sales of nontargeted exporters in the protected market also increased in line with that of targeted exporters (or at least did not offset the increase in sales of targeted exporters). Also, in context of the great trade collapse, these markets probably shrank by less than the world market in the same product.

In Grossman and Helpman’s (1994) political economy model of protection, in contrast, equilibrium tariffs are higher, ceteris paribus, for politically organized industries with low import penetration, because industry shareholders gain from an increase in the domestic price, while consumers incur fewer inefficiency losses with lower imports. Our evidence suggests that instead higher import penetration would lead to higher protection, at least in the short term.

Meanwhile, there seems to be strong evidence of specification 4 being preferred to 5 and 6, but we nonetheless include specification 6 in our robustness tests because of its comprehensiveness. Previous versions of this paper instead employed F-tests for model comparison, with very similar results. F-tests have some drawbacks in requiring normality of errors, but are asymptotically valid (Greene, 2003). Adjusted R 2 values of our models are low relative to gravity equations in levels. The dependent variable here—monthly product-level bilateral trade—is much more volatile. Not surprisingly then, even large sets of fixed effects do not have enormous explanatory power, as measured by adjusted R 2, because even within-group idiosyncratic fluctuations are high. Although the estimated coefficients on the protectionist dummies are highly statistically significant, these discrete variables take nonzero values for a small share of observations. They cannot be expected to boost the overall R 2 substantially, even though they do a good job in explaining the (few) observations affected by protectionism.

In calculating aggregate trade impacts, any such bias would offset against trade flow values, resulting in unbiased aggregate impacts.

We thank an anonymous referee for pointing this out.

Import restrictions, our main variable of interest, break down as follows. Observations affected by one import restriction numbered 56,050 (0.57 percent of the total sample). There were 4,780 observations, 218 observations, and 2 observations contemporaneously affected by two, three, and four import restrictions, respectively. The remainder of the sample (9,817,431 observations) was unaffected by import restrictions.

The data section elaborates further on the motivation for choosing the last quarter of 2009 as a basis for calculating aggregate trade impacts.

If we instead used specification 4 estimates, the impact would be 0.14 percent of world trade, based solely on import restrictions, which are now attributed a larger impact. Specifications 5 and 6, which feature even more comprehensive controls, return slightly larger estimates, again based on import restrictions only.

Table 2, lower panel, summarizes these impacts for all specifications in percent of world trade and in values. Impacts are calculated by multiplying the product-level coefficient estimates by the “affected quarterly trade” (the value of trade in country-pair-product combinations that were affected by new measures). Table 2 also provides the number of measures implemented and number of observations affected.

The lower panel of Table 2 illustrates dollar values of the impact based on quarterly trade flows in 2009:Q4. Recognizing that trade in 2009 was depressed by the crisis, the $30–$35 billion impact stated here is calculated based on annual global trade in 2008 and 2010.

Calculated as 0.21*(508/314), where 508 is the total number of measures in GTA and 314 is the number of measures that could be included in our estimation sample, including export measures (Table 1). However, excluded measures were tilted toward behind-the-border measures, whose effect is surrounded by somewhat more uncertainty. Therefore such extrapolation is difficult.

We also tested the significance of green measures in initial stages of this research with similar results. See footnote 11 “Amber” measures are excluded given the uncertainty….

These data were obtained from the UN TRAINS database with missing observations filled with data from the WTO’s Integrated Database (IDB).

Henn and McDonald (2011) report two additional robustness tests. The first restricts the protectionist variable in Equation (1) to binary (0, 1) values, which leaves baseline results unchanged. The second uses changes in log trade volumes as the dependent variable and finds that results still broadly hold, although precision and magnitudes of estimates are reduced.

We thank an anonymous referee for highlighting this. Variation would be preserved relative to fixed effects particularly in cases where the reference exporter is not affected by protectionism in a certain import market, while most other exporters are subject to such protectionism.

Head, Mayer, and Ries (2010) study on aggregate trade data proceeds in the analog way, by introducing time dummies. In light of the high dimensionality of the product-time dimension and our large data set, we cannot introduce a set of dummy variables into estimation without reaching computational constraints. Preestimation demeaning delivers the same results after standard errors are adjusted for degrees of freedom. A downside of having to demean for product-time is that we can only do such demeaning for one effect given that our panel is unbalanced. This prevents us from introducing time-varying country-pair fixed effects into the tetrads equation. Note that for tetraded variables, the protectionist dummy here may take integer values between 2 and −2 for the simplest case of only one protectionist measure affecting each observation and no measures being removed.

Although this could introduce selection bias, if observations are lost in a fashion correlated with incidence of protectionist actions, we believe this possibility to be remote.

Results are unchanged if, instead of simple averages, we use medians or weighted averages with the number of observations as weights.

It is not straightforward to devise metrics to evaluate the importance in our data set of trade flows falling to zero in response to new protectionist measures. This is because high frequency product-level trade data often show zeros for certain months or quarters given lumpiness of shipments. Therefore, more intricate decision rules, such as in Asmundsen (2012), would have to be devised to define how many months of zero values are necessary to consider that trade flows in a country-pair-product category have ceased. This would be further complicated by the differencing in our estimation equation. Given that Duads and Tetrads results are broadly in line with our baseline findings, we do not explore this issue further.

In addition to these limitations, Martin and Pham (2009) have shown PPML to yield “severely biased estimates” when large values of zeros have been generated by a limited dependent variable process. For aggregate trade data, Head, Mayer, and Ries (2010, p.4) document a number of further important shortfalls of PPML.

Otherwise the only way to eliminate the country-pair-specific effects in a PPML setup would be to divide the contemporaneous multiplicative gravity equation by its 12-month lagged equivalent. This would result again in missing values for imports where the 12-month lagged value is zero.

For the latter, they use a regional agreement dummy in their study.

This subsection explores the effects by different types of measure and summarizes results by country groupings. Henn and McDonald (2011) provide more detail on the latter and also include additional results by sectors and time periods.

Bown (2010), who reviews developments in the use of antidumping, safeguards, and countervailing duties, notes that their use rose by ¼ in 2008–09 as measured by the coverage of product lines by major users.

In regression 7, the aggregate impact of tariffs and import bans is slightly higher, but it results from a statistically insignificant product-level coefficient.

Behind-the-border measures remain insignificant throughout in the TVIMP fixed effects specifications.

References

Abowd, John M., Francis Kramarz, and David N. Margolis, 1999, “High Wage Workers and High Wage Firms,” Econometrica, Vol. 67, No. 2, pp. 251–333.

Ahn, JaeBin, Mary Amiti, and David E. Weinstein, 2011, “Trade Finance and the Great Trade Collapse,” American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 3, pp. 298–302.

Alessandria, George, Joe Kaboski, and Virgiliu Midrigan, 2010, “The Great Trade Collapse of 2008–09: An Inventory Adjustment?,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 254–94.

Amiti, Mary and David Weinstein, 2009, “Exports and Financial Shocks,” Working Paper 15556 (National Bureau of Economic Research).

Anderson, James E. and Eric van Wincoop, 2003, “Gravity with Gravitas: A Solution to the Border Puzzle,” American Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 1, pp. 170–92.

Anderson, James E. and Eric van Wincoop, 2004, “Trade Costs,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 691–751.

Anderton, Robert and Tadios Tewolde, 2011, “The Global Financial Crisis: Understanding the Global Trade Downturn and Recovery,” The World Economy, Vol. 34, No. 5, pp. 741–63.

Asmundson, Irena, 2012, More World Trade Flows: An Updated Dataset, Mimeo (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Baier, Scott L. and Jeffrey H. Bergstrand, 2007, “Do Free Trade Agreements Actually Increase Members’ International Trade?,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 71, No. 1, pp. 72–95.

Baldwin, Richard E. ed., 2009, “The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences, and Prospects,” Available via the Internet: www.voxeu.org.

Baldwin, Richard E. and Simon Evenett eds., 2009, “The Collapse of Global Trade, Murky Protectionism, and the Crisis: Recommendations for the G-20,” Available via the Internet: www.voxeu.org.

Baldwin, Richard E. and Daria Taglioni, 2006, “Gravity for Dummies and Dummies for Gravity Equations,” Working Paper 12516 (National Bureau of Economic Research).

Baldwin, Richard E. and Daria Taglioni, 2009, “The Great Trade Collapse and Trade Imbalances,” Available via the Internet: www.voxeu.org.

Bems, Rudolfs, Robert C. Johnson, and Kei-Mu Yi, 2010, “Demand Spillovers and the Collapse of Trade in the Global Recession,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 295–326.

Bown, Chad P., 2010, “Taking Stock of Antidumping, Safeguards, and Countervailing Duties, 1990–2009,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5436.

Bussiere, Matthieu, Emilia Perez-Barreiro, Roland Straub, and Daria Taglioni, 2011, “Protectionist Responses to the Crisis: Global Trends and Implications,” The World Economy, Vol. 34, No. 5, pp. 826–52.

Cameron, A., Colin Jonah B. Gelbach, and Douglas L. Miller, 2011, “Robust Inference with Multiway Clustering,” Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 238–49.

Cernat, Lucian and Nuno Souza, 2010, “The Impact of Crisis-driven Protectionism on EU Exports: The ‘Russian Doll’ Effect,” Available via the Internet: www.voxeu.org.

Chen, Natalie and Dennis Novy, 2011, “Gravity, Trade Integration, and Heterogeneity across Industries,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 206–21.

Cipollina, Maria and Luca Salvatici, 2010, “Reciprocal Trade Agreements in Gravity Models: A Meta-Analysis,” Review of International Economics, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 63–80.

Decreux, Yvan and Lionel Fontagne, 2011, “Economic Impact of Potential Outcome of DDA,” CEPII Working Paper No. 2011-23.

Driscoll, John C. and Aart C. Kraay, 1998, “Consistent Covariance Estimation with Spatially Dependent Panel Data,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 80, No. 4, pp. 549–60.

Egger, Peter, Mario Larch, Kevin E. Staub, and Rainer Winkelmann, 2011, “The Trade Effects of Endogenous Preferential Trade Agreements,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 113–43.

Eicher, Theo S., Christian Henn, and Chris Papageorgiou, 2012, “Trade Creation and Diversion Revisited: Accounting for Model Uncertainty and Natural Trading Partner Effects,” Journal of Applied Econometrics, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 296–321.

Eicher, Theo S. and Christian Henn, 2011a, “In Search of WTO Trade Effects: Preferential Trade Agreements Promote Trade Strongly, but Unevenly,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 83, No. 2, pp. 137–53.

Eicher, Theo S. and Christian Henn, 2011b, “One Money One Market: A Revised Benchmark,” Review of International Economics, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 419–35.

Essaji, Azim, 2008, “Technical Regulations and Specialization in International Trade,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 76, No. 2, pp. 166–176.

Evenett, Simon ed., 2010, “Managed Exports and the Recovery of World Trade: The 7th GTA Report,” Available via the Internet: www.globaltradealert.org.

Francois, Joe, Brad McDonald, and Hakan Nordstrom, 1996, “A User’s Guide to Uruguay Round Assessments,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 1410.

Francois, Joe and Ken Reinert eds., 1997, Applied Methods for Trade Policy Analysis: A Handbook (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Greene, William H., 2003, Econometric Analysis (Princeton, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 5th ed).

Grossman, Gene M. and Elhanan Helpman, 1994, “Protection for Sale,” American Economic Review, Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 833–850.

Guimaraes, Paulo and Pedro Portugal, 2010, “A Simple Feasible Procedure to Fit Models with High-Dimensional Fixed Effects,” The Stata Journal, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 628–49.

Haddad, Mona, Ann Harrison, and Catherine Hausman, 2010, “Decomposing the Great Trade Collapse: Products, Prices, and Quantities in the 2008–2009 Crisis,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 16253.

Hansen, Lars Peter and Robert J. Hodrick, 1980, “Forward Exchange Rates as Optimal Predictors of Future Spot Rates: An Econometric Analysis,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 88, No. 5, pp. 829–53.

Head, Keith and Thierry Mayer, 2000, “Non-Europe: the Magnitude and Causes of Market Fragmentation in the EU,” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, Vol. 136, No. 2, pp. 285–314.

Head, Keith and Thierry Mayer, 2014, “Gravity Equations: Workhorse, Toolkit, Cookbook,” in Handbook of International Economics, Vol. 4, ed. by Gita Gopinath, Elhanan Helpman, and Kenneth Rogoff (Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.).

Head, Keith, Thierry Mayer, and John Ries, 2010, “The Erosion of Colonial Trade Linkages after Independence,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 81, No. 1, pp. 1–14.

Head, Keith and John Ries, 2001, “Increasing Returns Versus National Product Differentiation as an Explanation for the Pattern of U.S.-Canada Trade,” American Economic Review, Vol. 91, No. 4, pp. 858–76.

Helpman, Elhanan, Marc Melitz, and Yona Rubinstein, 2008, “Estimating Trade Flows: Trading Partners and Trading Volumes,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 123, No. 2, pp. 441–87.

Henn, Christian and Brad McDonald, 2010, “Avoiding Protectionism,” Finance and Development, March, pp. 20–23.

Henn, Christian and Brad McDonald, 2011, “Protectionist Responses to the Crisis: Damage Observed in Product-Level Trade,” IMF Working Paper 11/139 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Hoekman, Bernard and Alessandro Nicita, 2011, “Trade Policy, Trade Costs, and Developing Country Trade,” World Development, Vol. 39, No. 12, pp. 2069–79.

Hummels, David and James Levinsohn, 1995, “Monopolistic Competition and International Trade: Reconsidering the Evidence,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 110, No. 3, pp. 799–836.

Kee, Hiau Looi, Cristina Neagu, and Alessandro Nicita, 2010, “Is Protectionism on the Rise? Assessing National Trade Policies during the Crisis of 2008,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5274.

Levchenko, Andrei A., Logan Lewis, and Linda L. Tesar, 2009, “The Collapse of International Trade during the 2008–9 Crisis: In Search of the Smoking Gun,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 214–253.

Martin, Philippe, Thierry Mayer, and Mathias Thoenig, 2008, “Make Trade Not War?,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 75, No. 3, pp. 865–900.

Martin, Will and Cong S. Pham, 2009, Estimating the Gravity Model when Zero Trade Flows are Frequent, mimeo (Washington, DC: World Bank).

Martins, Joaquim Oliveira and Sonia Araujo, 2009, “The Great Synchronization: Tracking the Trade Collapse with High-frequency Data,” in The Collapse of Global Trade, Murky Protectionism, and the Crisis: Recommendations for the G-20, ed. by Baldwin, Richard E. and Simon Evenett. Available via the Internet: www.voxeu.org.

Minor, Peter and Marinos Tsigas, 2008, “Impacts of Better Trade Facilitation in Developing Countries: Analysis with a New GTAP Database for the Value of Time in Trade,” 11th Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis, Helsinki, Finland.

Newey, Whitney K., and Kenneth D. West, 1987, “A Simple, Positive Semi-Definite, Heteroskedasticity and Autocorrelation Consistent Covariance Matrix,” Econometrica, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 703–8.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2010, “Trade and Economic Effects of Responses to the Economic Crisis,” OECD Trade Policy Studies.

Rose, Andrew K., 2000, “One Money, One Market: The Effect of Common Currencies on Trade,” Economic Policy, Vol. 15, No. 30, pp. 7–46.

Rose, Andrew K., 2004, “Do We Really Know that the WTO Increases Trade?,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 1, pp. 98–114.

Rogers, William H., 1993, “sg 17: Regression Standard Errors in Clustered Samples,” Stata Technical Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 13, pp. 19–23, In Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints, Vol. 3, pp. 88–94 (College Station, TX: Stata Press).

Shingal, Anirudh, 2009, “The Impact of Cross-Border Discrimination on Japanese Exports: A Sectoral Analysis,” in The Unrelenting Pressure of Protectionism: The 3rd GTA Report, ed. by Simon Evenett (London: Centre for Economic Policy Research).

Santos Silva, J. and S. Tenreyro, 2006, “The Log of Gravity,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 88, No. 4, pp. 641–58.

Stock, James H. and Mark W. Watson, 2008, “Heteroskedasticity-Robust Standard Errors for Fixed Effects Panel Data Regression,” Econometrica, Vol. 76, No. 1, pp. 155–74.

Trefler, Daniel, 1995, “The Case of Missing Trade and Other Mysteries,” American Economic Review, Vol. 85, No. 5, pp. 1029–46.

UNCTAD/WTO. 2012, A Practical Guide to Trade Policy Analysis (Geneva, Switzerland: UNCTAD/WTO).

Wooldridge, Jeffrey M., 2002, Econometric Analysis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

World Trade Organization (WTO). 2013, Report on G-20 Trade Measures (Mid-October 2012 to Mid-May 2013). 17 June 2013, Geneva, Switzerland.

Additional information

*The original research for this paper was conducted while the authors were economists in the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Christian Henn is currently also affiliated with the World Trade Organization, and Brad McDonald with the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The paper does not represent the position or opinions of the IMF or its Executive Board, the WTO or its Members, the United States Treasury, or the United States Government, or the position of any of these organizations’ staff members, apart from the authors. Any errors are the responsibility of the authors. The authors thank seminar participants at the European Trade Study Group’s 2011 Annual Conference in Copenhagen; the July 2011 WTO Symposium on “The Financial and Economic Crises and the Role of the WTO”; the July 2011 EcoMod conference in Ponta Delgada, Portugal; and the December 2011 Joint IMF-World Bank-WTO Trade Conference. They also thank Richard Baldwin, Cosimo Beverelli, Joe Francois, Alexander Keck, Rod Ludema, Håkan Nordström, Chris Papageorgiou, Ranil Salgado and two anonymous referees for suggestions on this research; and Tushara Ekanayake, Emmanuel Hife, Yoichiro Kimura, Ioana Niculcea, and Nicolas Young for outstanding research assistance.