Abstract

In countries with secure property rights, corporate transparency improves investment efficiency and increases growth by alleviating information asymmetry. However, in countries with insecure property rights, greater transparency can increase the risk of government expropriation. Therefore some firms that would benefit most from transparency cannot take full advantage of it, as they set sub-optimal transparency levels. Using data from 59 industries in 69 countries, we find that in countries with weak property rights protection, industries that would benefit the most from transparency exhibit worse investment efficiency and grow more slowly than industries that can efficiently operate at minimal levels of transparency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We consider transparency in a broad sense. In our view, transparency is determined by a set of market mechanisms that facilitate information acquisition and processing by investors; a market structure that enhances informational content for consumers and suppliers and makes the contract between economic parties more efficient.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 is perhaps the most well-known recent legislation aimed at increasing transparency in financial markets. Canada, Japan, and Australia, among others, have enacted similar legislation.

One may argue that if expropriation is anticipated, such an expectation would be reflected in IPO pricing, giving shareholders a fair return. However, our argument builds upon the idea that firms reduce transparency in anticipation of expropriation. See a more detailed discussion in the Results section under Alternative Explanations. We would like to thank an anonymous referee for pointing this out.

The costs and benefits of transparency are shown to vary across industries. Admati and Pfleiderer (2000) discuss how incentives to disclose information depend on industry competitiveness. A large degree of variation in transparency has also been documented empirically by Bharath, Pasquariello, and Wu (2009).

As a robustness check we confirm that the results are not changed if clustering is performed by industry or by both country and industry.

We do not include the transparency norm level in regression (1) because, for the same industry, it does not vary across countries.

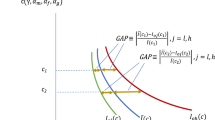

Using actual numbers, the transparency gap for the petroleum industry in Russia is large and equal to 1.490. It is the difference between its transparency norm of 1.570 (calculated using numbers for the US petroleum industry) and the low transparency practice of 0.080 observed among Russian companies.

When a firm is present in both OSIRIS and Worldscope, and there is a discrepancy in accounting numbers (less than 1% of the sample of firms), we rely on a better known dataset, Worldscope.

We exclude 1998 because of the Asian financial crises, which could contaminate our measures.

Industry and market indexes exclude the firm in question to avoid spurious correlation between individual returns and the indexes.

PCA is a statistical method to reduce multidimensional datasets to lower dimensions. The PCA can be viewed as an orthogonal linear transformation that alters the data to a new coordinate system such that the greatest variance by any projection of the data comes to lie on the first coordinate (called the first principal component), the second greatest variance on the second coordinate, and so on. See Stevens (1986) for details.

The results remain robust if we control for past performance (measured as ROA per total assets) in Eq. (8), as suggested by Ashbaugh et al. (2003).

Is financial development just a proxy for the level of property rights protection? While the correlation between financial development and expropriation risk is negative (−0.43), there are some exceptions. Several countries (e.g., South Africa, Malaysia, Jordan) have well-developed financial markets but weak property rights. On the other hand, countries like Finland, Denmark, and New Zealand respect property rights but have less developed financial markets.

Presumably, the cost of making governance weaker varies across different categories of governance. For example, it is easier for companies to reduce transparency than to weaken governance by firing independent directors.

More specifically, on page 1614 Stulz (2005) writes: “Greater transparency and boards dominated by outside directors are often viewed as hallmarks of good governance. When there are significant risks of expropriation by the state, neither of these two good-governance attributes are likely to enhance the wealth of shareholders. While transparency increases firm value, in that it makes it harder for insiders to expropriate from investors, it also decreases firm value because it makes expropriation by the state easier”.

We exclude the disclosure component to concentrate on governance provisions other than transparency.

These results are available from the authors upon request.

The corporate tax rate is taken from Djankov et al. (2009). The corporate tax burden index is from the Economist Intelligence Unit. It is measured as the assessment of how corporate taxation impedes the development of private businesses.

More specifically, the interaction of corporate tax burden has a significantly negative effect on investment efficiency in the presence of expropriation risk, and on industry growth in the presence of political risk. The main interaction effect of aggregate transparency gap remains negative and highly significant across all specifications. We do not tabulate the results, to save space; they are available from the authors upon request.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. 2005. Unbundling institutions. Journal of Political Economy, 113 (5): 949–995.

Admati, A., & Pfleiderer, P. 2000. Forcing firms to talk: Financial disclosure regulation and externalities. Review of Financial Studies, 13 (3): 479–519.

Aggarwal, R., & Williamson, R. 2006. Did new regulations target the relevant corporate governance attributes?, Working paper, Georgetown University.

Aggarwal, R., Erel, I., Stulz, R., & Williamson, R. 2009. Differences in governance practices between US and foreign firms: Measurement, causes, and consequences. Review of Financial Studies, 22 (8): 3131–3169.

Akerlof, 1970. The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84 (3): 488–500.

Alexeev, M., Janeba, E., & Osborne, S. 2004. Taxation and evasion in the presence of extortion by organized crime. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32 (3): 375–388.

Ashbaugh, H., LaFond, R., & Mayhew, B. 2003. Do nonaudit services compromise auditor independence? Further evidence. Accounting Review, 78 (3): 611–639.

Bharath, S., Pasquariello, P., & Wu, G. 2009. Does asymmetric information drive capital structure decisions? Review of Financial Studies, 22 (8): 3211–3243.

Blanchard, O., & Kremer, M. 1997. Disorganization. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112 (4): 1091–1126.

Bruno, V., & Claessens, S. 2007. Corporate governance and regulation: Can there be too much of a good thing?, Working paper, The World Bank.

Caprio, L., Faccio, M., & McConnell, J. 2008. Sheltering corporate assets from political extraction, Working paper, Purdue University.

Chaney, P., Faccio, M., & Parsley, D. 2007. The quality of accounting information in politically connected firms, Working paper, Purdue University.

Claessens, S., & Laeven, L. 2003. Financial development, property rights, and growth. Journal of Finance, 58 (6): 2401–2436.

Collins, D., Kothari, P., Shanken, J., & Sloan, R. 1994. Lack of timeliness and noise as explanations for the low contemporaneous return-earnings association. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 18 (3): 289–324.

Core, J. 2001. A review of the empirical disclosure literature: Discussion. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31 (1–3): 441–456.

DeAngelo, L. 1988. Managerial competition, information costs, and corporate governance: The use of accounting performance measures in proxy contests. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 10 (1): 3–37.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. 2008. The law and economics of self-dealing. Journal of Financial Economics, 88 (3): 430–465.

Djankov, S., Ganser, T., McLiesh, C., Shleifer, A., & Ramalho, R. 2009. The effect of corporate taxes on investment and entrepreneurship, Working paper, Harvard University.

Durnev, A., & Fauver, L. 2008. Stealing from thieves: Firm governance and performance when states are predatory, Working paper, McGill University.

Durnev, A., & Guriev, S. 2008. The resource curse: A corporate transparency channel, Working paper, CEFIR.

Durnev, A., & Kim, E. 2005. To steal or not to steal: Firm attributes, legal environment, and valuation. Journal of Finance, 60 (3): 1461–1493.

Friedman, E., Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobaton, P. 2000. Dodging the grabbing hand: The determinants of unofficial activity in 69 countries. Journal of Public Economics, 76 (3): 459–493.

Hall, R., & Jones, C. 1999. Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114 (1): 83–116.

Hansen, L. 1982. Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica, 50 (4): 1029–1054.

Hart, O., & Tirole, J. 1988. Contract renegotiation and Coasian dynamics. Review of Economic Studies, 55 (4): 509–540.

Healy, P., & Palepu, K. 2001. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31 (1–3): 405–440.

Henisz, W. 2002. The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11 (2): 355–389.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobaton, P. 1998. Regulatory discretion and the unofficial economy. American Economic Review, 88 (2): 387–392.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. 1995. Institutions and economic performance: Cross-country tests using alternative institutional measures. Economics and Politics, 7 (3): 207–227.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1999. The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 15 (1): 222–279.

Levchenko, A. 2007. Institutional quality and international trade. Review of Economic Studies, 74 (3): 791–819.

Llorente, G., Michaely, R., Saar, G., & Wang, J. 2002. Dynamic volume-return relation of individual stocks. Review of Financial Studies, 15 (4): 1005–1047.

Lundholm, R., & Myers, L. 2002. Bringing the future forward: The effect of disclosure on the returns-earnings relation. Journal of Accounting Research, 40 (3): 809–839.

Morck, R., Yeung, B., & Yu, W. 2000. The information content of stock markets: Why do emerging markets have synchronous stock price movements? Journal of Financial Economics, 58 (1–2): 215–260.

Petersen, M. 2009. Estimating standard errors in finance panel datasets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22 (1): 435–480.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. 1998. Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88 (3): 559–586.

Rose-Ackerman, S. 1975. The economics of corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 4 (2): 187–203.

Russia Profile Magazine. 2007. Corporate governance in Russia. 3 March: 7.

Stevens, J. 1986. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Stulz, R. 2005. The limits of financial globalization. Journal of Finance, 60 (4): 1595–1638.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1994. Politicians and firms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109 (4): 995–1025.

Trueman, B. 1986. Why do managers voluntarily release earnings forecasts? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 8 (1): 53–71.

Verdi, R. 2006. Financial reporting quality and investment efficiency, Working paper, MIT.

Warner, J., Watts, R., & Wruck, K. 1988. Stock prices and top management changes. Journal of Financial Economics, 20 (1–2): 461–493.

Watts, R., & Zimmerman, J. 1978. Towards a positive theory of the determination of accounting standards. The Accounting Review, 53 (1): 112–134.

Watts, R., & Zimmerman, J. 1986. Positive theory of accounting. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Wurgler, J. 2000. Financial markets and the allocation of capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 58 (1–2): 187–214.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for helpful comments and suggestions by the editor, Lemma Senbet, anonymous referees, Henk Berkman, Stijn Claessens, Amrita Nain, Maria Petrova, Bernard Yeung, and the participants at the 2009 Darden International Finance Conference, Concordia University seminar, and Massey University seminar. Art Durnev's research is supported by Institut de Finance Mathématique de Montréal (IFM2) and the Social Sciences & Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Vihang Errunza's research is supported by the Bank of Montreal chair in finance and banking, IFM2 and SSHRC. We thank Pat Akey for superb research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by Lemma Senbet, Area Editor, 24 June 2009. This paper has been with the authors for two revisions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Durnev, A., Errunza, V. & Molchanov, A. Property rights protection, corporate transparency, and growth. J Int Bus Stud 40, 1533–1562 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.58

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.58