Abstract

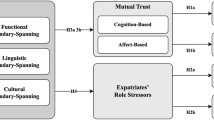

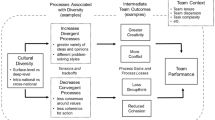

Do international or non-international differences between members matter most for multinational corporation (MNC) teams? We consider two types of international differences, arising from geographic locations and national origins, and two types of non-international differences, arising from structural affiliations and demographic attributes. Examining the barriers to knowledge seeking between MNC team members, we argue that whether international or non-international differences create greater barriers depends on whether they are position-based or person-based. Using the Social Relations Model to analyze 13,616 dyadic interactions among 2090 members of 289 teams in a large MNC, we find that, for both international and non-international differences, those that are position-based (i.e., geographic and structural differences) created greater barriers than those that are person-based (i.e., nationality and demographic differences). In addition, familiarity from a prior team reduced the barriers created by international and non-international differences that are position-based more than those that are person-based. We discuss the implications of our study for understanding the micro-foundations of knowledge flows in MNCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our focus on interpersonal knowledge seeking within MNC teams complements research on knowledge search across MNC subsidiaries as well as knowledge sourcing from outside MNCs (e.g., Almeida, 1996; Cantwell, 2009; Jeppesen & Lakhani, 2010; see Laursen, 2012 for a recent review). We use the term “seeking” rather than “search” or “sourcing” to capture the more focused nature of this behavior, which targets a particular individual for knowledge.

Concerns about communication costs between team members who are different may be reinforced by the lower interpersonal attraction that often accompanies interpersonal differences, as emphasized by the literatures on similarity-attraction and homophily (e.g., Byrne, 1971; McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001).

Indeed, to the extent that differences in age, tenure, or education level are associated with different levels (rather than domains) of task-related knowledge, the barriers created by these differences may even be reduced as team members see potential value in seeking knowledge from those, for example, who are older, more senior, or more educated than themselves.

We also created an additional continuous measure of geographic differences using distance in miles between the country locations of the two members of a dyad; this measure was highly correlated with the dichotomous measures (r=0.69, r=0.90, r=0.81) and gave consistent results.

Nationality may be based on citizenship as well as birth, and the cross-cultural literature points out that individuals may have more than one citizenship as well as bicultural or multicultural identities (see Leung, Bhagat, Buchan, Erez, & Gibson, 2005). While recognizing that other approaches are possible (and should yield consistent results), in this study we focus on national origins based on birthplace.

Following Hansen and Løvås (2004), we also created an additional continuous measure of nationality differences using the Hofstede dimensions of cultural distance between each dyad’s countries of origin (Hofstede, 1991); this measure was highly correlated with the dichotomous measures (r=0.88, r=0.71, r=0.53) and gave consistent results.

We focused on the demographic attributes with most direct relevance to knowledge seeking in MNC teams. However, we also conducted empirical analyses with gender, and found the same pattern of results as for age, tenure, and education level; data on race were not available.

In addition, we constructed two alternative directional measures to capture whether the seeker was older, more experienced, or more educated than the target, and whether the seeker was younger, less experienced, or less educated than the target. We also constructed an alternative distance measure to capture the extent of the differences in age, tenure, and education between the seeker and target. These alternative measures gave the same patterns of results as the dichotomous measures.

While it is possible that team members had worked together on multiple teams, it was not very common in the MNC we studied to work with the same people repeatedly (in our sample, only 12% of pairs reported working together in a previous team). We would expect that two team members who had worked with each other on multiple previous teams would be even more likely to overcome the barriers created by differences between them than those who had only worked together once.

Variance inflation factors for the difference variables in this model were all below 3.0, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern.

While we recognize the possibility of common-method bias in member-rated performance measures, knowledge seeking was reported at the dyad level while performance was reported at the team level, reducing its likelihood in our study. In addition, a Harman’s single-factor test for common-method bias did not indicate cause for concern.

References

Aiken, L., & West, S. 1991. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Almeida, P. 1996. Knowledge sourcing by foreign multinationals: Patent citation analysis in the US semiconductor industry. Strategic Management Journal, 17 (Winter Special Issue): 155–165.

Ancona, D., & Caldwell, D. 1992. Demography and design: Predictors of new product team performance. Organization Science, 3 (3): 321–341.

Bartlett, C. A., Ghoshal, S., & Birkinshaw, J. 2003. Transnational management: Text, cases and readings in cross border management, 4th edn. Boston: McGraw-Hill–Irwin.

Bechky, B. 2003. Sharing meaning across occupational communities: The transformation of understanding on a production floor. Organization Science, 14 (3): 312–330.

Bhagat, R. S., Kedia, B. L., Harveston, P. D., & Triandis, H. C. 2002. Cultural variations in the cross-border transfer of organizational knowledge: An integrative framework. Academy of Management Review, 27 (2): 204–221.

Birkinshaw, J., & Morrison, A. J. 1995. Configurations of strategy and structure in subsidiaries of multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 26 (4): 729–754.

Borgatti, S. P., & Cross, R. 2003. A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Management Science, 49 (4): 432–445.

Brandon, D. P., & Hollingshead, A. 2004. Transactive memory systems in organizations: Matching tasks, expertise, and people. Organization Science, 15 (6): 633–644.

Brannen, M. Y. 2004. When Mickey loses face: Recontextualization, semantic fit, and the semiotics of foreignness. Academy of Management Review, 29 (4): 593–616.

Byrne, D. 1971. The Attraction Paradigm. New York: Academic.

Cantwell, J. 2009. Location and the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 40 (1): 35–41.

Cohen, S. G., & Bailey, D. E. 1997. What makes teams work: Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. Journal of Management, 23 (3): 239–290.

Cramton, C. 2001. The mutual knowledge problem and its consequences for dispersed collaboration. Organization Science, 12 (3): 346–371.

Cross, R., & Cummings, J. N. 2004. Tie and network correlates of individual performance in knowledge-intensive work. Academy of Management Journal, 47 (6): 928–937.

Cyert, R., & March, J. 1963. A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Dougherty, D. 1992. Interpretive barriers to successful product innovation in large firms. Organization Science, 3 (2): 179–202.

Doz, Y., Santos, J., & Williamson, P. 2001. From global to metanational: How companies win in the knowledge economy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Earley, P. C., & Gibson, C. B. 2002. Multinational work teams: A new perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Earley, P. C., & Mosakowski, E. 2000. Creating hybrid team cultures: An empirical test of transnational team functioning. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1): 26–49.

Espinosa, A., Cummings, J., Wilson, J., & Pearce, B. 2003. Team boundary issues across multiple global firms. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19 (4): 159–192.

Espinosa, A., Slaughter, S., Kraut, R., & Herbsleb, J. 2007. Familiarity, complexity, and team performance in geographically distributed software development. Organization Science, 18 (4): 613–630.

Faraj, S., & Sproull, L. 2000. Coordinating expertise in software development teams. Management Science, 46 (12): 1554–1568.

Foss, N. J., & Pedersen, T. 2002. Transferring knowledge in MNCs: The role of sources of subsidiary knowledge and organizational context. Journal of International Management, 8 (1): 49–67.

Foss, N. J., & Pedersen, T. 2004. Organizing knowledge processes in the multinational corporation: An introduction. Journal of International Business Studies, 35 (5): 340–349.

Foss, N. J., Husted, K., & Michailova, S. 2010. Governing knowledge sharing in organizations: Levels of analysis, governance mechanisms, and research directions. Journal of Management Studies, 47 (3): 455–482.

Galbraith, J. 1973. Designing complex organizations. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gibson, C., & Gibbs, J. 2006. Unpacking the concept of virtuality: The effects of geographic dispersion, electronic dependence, dynamic structure, and national diversity on team innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51 (3): 451–495.

Gruenfeld, D. H., Mannix, E. A., Williams, K. Y., & Neale, M. A. 1996. Group composition and decision making: How member familiarity and information distribution affect process and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67 (1): 1–15.

Gupta, A., & Govindarajan, V. 2000. Knowledge flows within multinational corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 21 (4): 473–496.

Haas, M. R. 2006. Acquiring and applying knowledge in transnational teams: The roles of cosmopolitans and locals. Organization Science, 17 (1): 313–332.

Hambrick, D. C., Davison, S. C., Snell, S. A., & Snow, C. C. 1998. When groups consist of multiple nationalities: Towards a new understanding of the implications. Organization Studies, 19 (2): 181–205.

Hansen, M., & Løvås, B. 2004. How do multinational companies leverage technological competencies? Moving from single to interdependent explanations. Strategic Management Journal, 25 (4): 801–822.

Hansen, M. T., Mors, M. L., & Løvås, B. 2005. Knowledge sharing in organizations: Multiple networks, multiple phases. Academy of Management Journal, 48 (5): 776–793.

Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., & Bell, M. P. 1998. Beyond relational demography: Time and the effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Academy of Management Journal, 41 (1): 96–107.

Hedlund, G. 1994. A model of knowledge management and the N-form corporation. Strategic Management Journal, 15 (S2): 73–90.

Hinds, P. J., & Mortensen, M. 2005. Understanding conflict in geographically distributed teams: The moderating effects of shared identity, shared context, and spontaneous communication. Organization Science, 16 (3): 290–307.

Hinds, P. J., Carley, K. M., Krackhardt, D., & Wholey, D. 2000. Choosing work group members: Balancing similarity, competence, and familiarity. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 81 (2): 226–251.

Hofmann, D., & Gavin, M. 1998. Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Implications for research in organizations. Journal of Management, 24 (5): 623–641.

Hofstede, G. 1991. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hoopes, D. G., & Postrel, S. 1999. Shared knowledge, “glitches”, and product development performance. Strategic Management Journal, 20 (9): 837–863.

Huckman, R. S., Staats, B. R., & Upton, D. M. 2009. Team familiarity, role experience, and performance: Evidence from Indian software services. Management Science, 55 (1): 85–100.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. 1999. Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Organization Science, 10 (6): 791–815.

Jehn, K., Northcraft, G., & Neale, M. 1999. Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict, and performance in workgroups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44 (5): 741–763.

Jensen, R., & Szulanski, G. 2004. Stickiness and the adaptation of organizational practices in cross-border knowledge transfers. Journal of International Business Studies, 35 (6): 508–523.

Jeppesen, L. B., & Lakhani, K. R. 2010. Marginality and problem-solving effectiveness in broadcast search. Organization Science, 21 (5): 1016–1033.

Katz, R., & Allen, T. J. 1982. Investigating the Not Invented Here (NIH) syndrome: A look at the performance, tenure, and communication patterns of 50 R&D project groups. R&D Management, 12 (1): 7–20.

Kenny, D., Kashy, D., & Cook, W. 2006. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Kilduff, M., & Krackhardt, D. 1994. Bringing the individual back in: A structural analysis of the internal market for reputation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 37 (1): 87–108.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. 1993. Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of the multinational corporation. Journal of International Business Studies, 24 (6): 625–645.

Lau, D. C., & Murnighan, J. K. 1998. Demographic diversity and faultlines: The compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 23 (2): 325–340.

Laursen, K. 2012. Keep searching and you’ll find: What do we know about variety creation and firms’ search activities for innovation? Industrial and Corporate Change, 21 (5): 1181–1220.

Lawrence, B.S. 1987. An organizational theory of age effects. In S. Bacharach, & N. DiTomaso (Eds), Research in the sociology of organizations. Vol. 5. 37–71. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Leung, K., Bhagat, R. S., Buchan, N. R., Erez, M., & Gibson, C. B. 2005. Culture and international business: Recent advances and their implications for future research. Journal of International Business Studies, 36 (4): 357–378.

Levin, D., & Barnard, H. 2013. Connections to distant knowledge: Interpersonal ties between more- and less-developed countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 44 (7): 676–698.

Lord, M. D., & Ranft, A. L. 2000. Organizational learning about new international markets: Exploring the internal transfer of local market knowledge. Journal of International Business Studies, 31 (4): 573–589.

Mannix, E., & Neale, M. 2005. What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6 (2): 31–55.

March, J. G. 1991. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2 (1): 71–87.

March, J., & Simon, H. 1958. Organizations. New York: Wiley.

Marschan-Piekkari, R., Welch, D., & Welch, L. 1999. In the shadow: The impact of language on structure, power and communication in the multinational. International Business Review, 8 (4): 421–440.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. 2001. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27 (1): 415–444.

Minbaeva, D., Pedersen, T., Björkman, I., Fey, C. F., & Park, H. J. 2003. MNC knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity, and HRM. Journal of International Business Studies, 34 (6): 586–599.

Monteiro, L. F., Arvisson, N., & Birkinshaw, J. 2008. Knowledge flows within multinational corporations: Explaining subsidiary isolation and its performance implications. Organization Science, 19 (1): 90–106.

Neeley, T. 2013. Language matters: Status loss and achieved status distinctions in global organizations. Organization Science, 24 (2): 476–497.

Newcomb, T. M. 1961. The acquaintance process. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Nisbett, R. E., & Ross, L. 1980. Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Nohria, N., & Ghoshal, S. 1997. The differentiated network: Organizing multinational corporations for value creation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. 1995. The knowledge-creating company. New York: Oxford University Press.

O’Reilly, C. A., Caldwell, D. F., & Barnett, W. P. 1989. Work group demography, social integration, and turnover. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34 (1): 21–37.

Pelled, L. 1996. Demographic diversity, conflict, and work group outcomes: An intervening process theory. Organization Science, 7 (6): 615–631.

Pfeffer, J. 1983. Organizational demography. In B. Staw, & L. Cummings (Eds), Research in organizational behavior. Vol. 5. 299–357. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Podolny, J., & Baron, J. 1997. Resources and relationships: Social networks and mobility in the workplace. American Sociological Review, 62 (5): 673–693.

Puranam, P., Raveendran, M., & Knudsen, T. 2012. Organization design: The epistemic interdependence perspective. Academy of Management Review, 37 (3): 419–441.

Reagans, R., Argote, L., & Brooks, D. 2005. Individual experience and experience working together: Predicting learning rates from knowing who knows what and knowing how to work together. Management Science, 51 (6): 869–881.

Reagans, R., Zuckerman, E., & McEvily, B. 2004. How to make the team: Social networks v demography as criteria for designing effective teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49 (1): 101–133.

Ryder, N. B. 1965. The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30 (6): 843–861.

Schulz, M. 2003. Pathways of relevance: Exploring inflows of knowledge into subunits of multinational corporations. Organization Science, 14 (4): 440–459.

Shapiro, D., Von Glinow, M., & Cheng, J. 2005. Managing multinational teams. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Singer, J., & Willett, J. 2003. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Snow, C., Snell, S., Davison, S., & Hambrick, D. 1996. Use transnational teams to globalize your company. Organizational Dynamics, 24 (4): 50–67.

Stasser, G. 1992. Pooling of unshared information during group discussions. In S. Worchel, W. Wood, & J. Simpson (Eds), Group process and productivity, 48–67. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Szulanski, G. 1996. Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17 (Winter Special Issue): 27–43.

Teece, D. J. 1977. Technology transfer by multinational firms: The resource cost of transferring technological know-how. The Economic Journal, 87 (346): 242–261.

Tushman, M. L., & Scanlan, T. J. 1981. Boundary spanning individuals: Their role in information transfer and their antecedents. Academy of Management Journal, 24 (2): 289–305.

Van den Bulte, C. R., & Moenaert, R. 1998. The effects of R&D team co-location on communication patterns among R&D, marketing, and manufacturing. Management Science, 44 (11): S1–S18.

Wageman, R. 1995. Interdependence and group effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40 (1): 145–180.

Yang, Q., Mudambi, R., & Meyer, K. E. 2008. Conventional and reverse knowledge flows in multinational corporations. Journal of Management, 34 (5): 882–902.

Zellmer-Bruhn, M., Maloney, M., Bhappu, A.D., & Salvador, R. 2008. When and how do differences matter? An exploration of perceived similarity in teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 107 (1): 41–59.

Zenger, T., & Lawrence, B. 1989. Organizational demography: The differential effects of age and tenure distributions on technical communication. Academy of Management Journal, 32 (2): 353–376.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article won the Academy of International Business’s Temple/AIB Best Paper Award and was a finalist for the Academy of Management’s Carolyn Dexter Best International Paper Award. We thank our editor, John Cantwell, and the anonymous reviewers for their guidance during the review process. We also thank Drew Carton, Tiziana Casciaro, Vit Henisz, Katherine Klein, Andrew Knight, Bill McEvily, Rachel Pacheco, Nancy Rothbard, and seminar participants at Bocconi, INSEAD, Rutgers, and Toronto for helpful comments. The research reported in this article was funded by NSF Award #IIS-0603667.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by John Cantwell, Editor-in-Chief, 4 June 2014. This article has been with the authors for three revisions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haas, M., Cummings, J. Barriers to knowledge seeking within MNC teams: Which differences matter most?. J Int Bus Stud 46, 36–62 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.37

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.37