Abstract

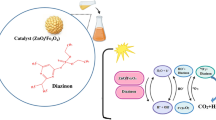

The degradation of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) was investigated in the aqueous solution of coated ZnO onto magnetite nanoparticale based on an advanced photocatalytic oxidation process. The photocatalysts were synthesized by coating of ZnO onto magnetite using precipitation method. The sample was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and vibration sample magnetometer (VSM). Besides, specific surface area was also determined by BET method. The four effective factors including pH of the reaction mixture, Fe3O4/ZnO magnetic nanoparticles concentration, initial MTBE concentration and molar ratio of [H2O2]/ [MTBE] were optimized using response surface modeling (RSM). Using the four-factor-three-level Box–Behnken design, 29 runs were designed considering the effective ranges of the influential factors. The optimized values for the operational parameters under the respective constraints were obtained at PH of 7.2, Fe3O4/ZnO concentration of 1.78 g/L, initial MTBE concentration of 89.14 mg/L and [H2O2]/ [MTBE] molar ratio of 2.33. Moreover, kinetics of MTBE degradation was determined under optimum condition. The study about core/shell magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) recycling were also carried out and after about four times, the percentage of the photocatalytic degradation was about 70%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) is commercially used as an octane enhancer for gasoline. It can reach underground water resources in different ways such as leaking underground fuel tanks, leaking pipelines, tank overfilling, faulty construction at gas stations, spillage from vehicle accidents and home owner releases may result in contamination of ground and surface water resources[1, 2]. The admissible limit of MTBE in drinking water is 20–40 ppb[3, 4] which has resulted in the prevention of this material to be used as a gasoline additive since May 2006[5]. The toxicity of MTBE to animals and humans is well documented. It is well known that MTBE is carcinogenic to animals, which is due to diverse properties such as the existence of ether bond and long sub-branches (more than one carbon) in its structure. MTBE is known as a very resistant substance to natural degradation[6, 7]. In recent decades, many technologies have been devoted to MTBE degradation in water. Some of these technologies included adsorption on granular activated carbon (GAC), air stripping, advance oxidation processes (AOPs) and biodegradation[8]. Over the past three decades, AOPs were efficient methods for degradation of organic contaminants. An AOP is a photocatalysis process, which mineralizes and degrades the organic contaminants, accordingly[9]. Many researchers have studied the photocatalytic degradation of MTBE using TiO2 and metal-doped TiO2 in either powder or thin film form[9–11]. However, most of these studies have followed the classical method of optimizing one factor at a time (OFAT), which is a time consuming and laborious task. This method, also, does not consider the interactions among the operational factors. However, Response surface methodology (RSM) can combine mathematics and statistics to analyze the relative significance of various operating parameters even in complicated systems[12]. Hence, this method can be applied to determine the optimum conditions of various reactions in a more convenient way resulting in saving time, labor, and cost.

Many types of photocatalytic reactors have been proposed according to respective application demands; among them, however, a slurry type reactor has proved to be most attractive for degrading organic contaminants which dissolve in water namely in terms of reaction surface area per unit volume of the reactor[13]. Nonetheless, one of the main problems of the suspended photocatalyst system is that it requires a separation step to recover photocatalyst particles. In this case, a suitable technique such as centrifugation or filtration step is required to reuse fine photocatalyst particles[14].

In this work Fe3O4/ZnO core/shell composite catalyst was synthesized and then characterized by XRD, SEM and VSM. The magnetic core enhancing the separation properties of suspended particles from solution and the photocatalytic properties of the outer shell zinc oxide are used to destroy organic contaminants in wastewater[15]. The four effective parameters, optimized using RSM, were (i) pH, (ii) coating of ZnO onto magnetite concentration, (iii) MTBE initial, and (iv) molar ratio of [H2O2]o/[MTBE]o. In the end, kinetics of MTBE degradation was determined in optimum condition.

Materials and methods

Materials

Methyl tert-butyl ether (99.9%), ferric chloride (FeCl3_6H2O), hydrogen peroxide (35% w/w), ferrous sulfate (FeSO4_7H2O), zinc acetate (ZnAC2_2H2O), aqueous ammonia (NH3_H2O) HNO3 and NaOH were purchased from Merk. ammonium carbonate ((NH4)2CO3) purchased from Dae jung.

Instruments

The instruments used for studying synthesized nanoparticles were XRD (Equinox 3000, Inel france), SEM (AIS2100, seron technology), BET (Autosorb-1, Quantachrome), 2 lamps (UVa 11W, Philips, Netherland), gas choromatography (GC) equipped with a helium ionization detector (HID) (Model GC-Acme 6100, Korea), vibration sample magnetometer (VSM, Meghnatis Daghigh Kavir Co., Iran), magnetic stirrer (Dalahan Labtech, LMS-1003) and digital pH meter (Elmetron, Cpc-501).

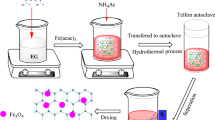

Preparation of the photocatalyst

A co-precipitation method was used to synthesize the Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs). Co-precipitation is a facile and convenient way to synthesize MNPs from aqueous salt solutions. This is accomplished by addition of ammonia to mixture of ferric chloride (0.5 M) and ferrous sulfate (0.5 M) with molar ratio of 1.75:1 under inert argon protection until pH value reached to 9. After 30 min stirring, the precipitate collected using a magnet and washed with deionized water until pH reached to 7. The modification process has been carried out via sonication of 4 g Fe3O4 and 200 ml sodium citrate (0.5 M) mixture for 20 min, which was then stirred for 12 h at 60°C under Ar protection. Afterwards, the precipitate collected and rinsed with acetone. The Fe3O4/ZnO core/shell MNPs were obtained by coating the modified Fe3O4 MNPs with direct precipitation using zinc acetate and ammonium carbonate. The modified Fe3O4 added to 100 ml of deionized water and sonicated for 20 min to make a stable ferrofluid. Then, 30 ml of this ferrofluid was added into a flask to form Fe3O4/ZnO composite. Two solutions were made by adding 12.16 g ZnAC2_2H2O and 7.6 g (NH4)2CO3 respectively into 100 ml of deionized water, and then, these two solutions were dropped slowly into the flask. Then the precipitate was collected and washed with water, aqueous ammonia (pH 9) and ethanol. Thereafter, the precipitate was dried under vacuum in 12 h and calcined according to desired calcination temperature and time[16].

Experimental set up

Photocatalytic degradation of MTBE was performed in a slurry batch reactor which was configured with a cylindrical glass with one liter in volume. In order to control the temperature of the reactions, the reactor was provided with a jacket for water circulation. Two lamps (11w, Philips, Netherland), which were immersed in the solution, were applied to supply the UV radiation in the reactor. The reactor was tightly sealed and in order to ensure well-mixing during irradiation, the nanoparticles were dispersed in the solution under magnetic stir. Besides, the air was injected into the reactor to supply the required amount of oxygen for the photocatalysis.

Experimental design by RSM method

Initially, preliminary experiments by following single factor study method were performed in order to find the most effective experimental parameters and their ranges affecting the photocatalytic degradation of MTBE. The selected parameters were catalytic dose, initial concentration of MTBE, initial concentration of H2O2 and pH.

The four selected experimental parameters were optimized using RSM considering them as independent variables and removal percentages of MTBE as response variables. By applying Box-Behnken design experiments, the required number of experiments were designed. This method was used because it is very efficient and does not contain any point at the vertices of the cubic region formed by the upper and lower limits of the variables. Such design along with RSM is widely applied for optimization of various physical, chemical and biological processes[17, 18].

As expressed in equation 1, the results were fitted to an empirical quadratic polynomial model for the aforesaid parameters using RSM.

where Y denotes the response variable, β0 the intercept, β1,β2,β3,β4 the coefficients of the independent variables, β11,β22,β33,β44 the quadratic coefficients, β12,β23,β31,β41,β42,β34 the interaction coefficients and A, B, C, D are the independent variables. Multivariate regression analysis and optimization process were performed by means of RSM and using Design Expert software (version 6.0.8, Stat Ease Inc., USA). The obtained values from analysis of variance (ANOVA) were found significant at p < 0.05. The optimum values for the independent variables were found using three-dimensional response surface analysis of the independent and dependent variables. The designed experiments plus the experimental and predicted values of the response are presented in Table 1. Also, the variations are shown in Figure 1.

Results and discussion

Characterization of MNPs

The X-ray diffraction pattern of modified Fe3O4 sample and Fe3O4/ZnO core/shell is presented in Figure 2. The average crystallite size was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation d= Kλ/(βcosθ) were about 13.9 nm (a), 11.2 nm (b) for modified Fe3O4 and Fe3O4, respectively. According to Figure 2b it is shown that after coating some enhances in peak intensity was caused by overlapping of Fe3O4 peaks.

In addition, Figure 3 represents SEM images of the samples. The SEM photographs of Fe3O4 MNPs before and after treating with sodium citrate are shown in Figure 3a and b respectively. It is shown that the dispersion of modified iron oxide is better than unmodified one. Figure 3c represents Fe3O4/ZnO core/shell particles which their average particle size was obtained about 60 nm.

The magnetic properties of MNPs are illustrated in Figure 4. It demonstrates that the coating process did not change the superparamagnetism of MNPs.

BET surface areas were determined using 3-points method for Fe3O4/ZnO nanoparticles which was 65 m2/gr.

Statistical analysis

To acquire a desirable model, The results are summarized in a common ANOVA table. The ANOVA table for removal percentage of MTBE response is exhibited in Table 2. The R-square is found to be 0.99, which is close to 1, which implies that about 99% of changes in the data can be explained by the model. The lack-of-fit P value of 0.3855 shows that the lack-of-fit is not significant relative to net error. For a predictive model the value of Lack of Fit should be not significant.

Following the experimental design (Table 2), empirical second order polynomial equations are developed for the removal percentage of MTBE in terms of the three independent variables as is expressed in equation 2.

The ANOVA of the second order quadratic polynomial model (F = 487.4, p < 0.0001) indicates that the model is significant, i.e. there is only a chance of 0.01% for occurrence of the model’s F-value due to the noise. The ANOVA regarding the regression models’s coefficient of the removal percentage of MTBE is presented in Table 3 as an extra tool to check the final model’s adequacy. The normal probability plot (scatter diagram) for the studentized residuals is illustrated in Figure 5. The points on this plot lie reasonably close to a straight line, confirming that the errors have a normal distribution with a zero mean and a constant. The curvature P-value < 0.0001 indicates that there is a significant curvature (as measured by the difference between the mean center points and the mean factorial points) in the design space. As a result, a linear model along with the interaction terms giving a twisted plane was not adequate to explain the response. Besides, plots of the residuals in Figure 6 reveal that they have no obvious pattern, and their structure is rather abnormal. Moreover, they indicate equal scatter above and below the x-axis, implying the proposed model’s adequacy, so there is no reason to suspect any violation. The optimum conditions for the maximum degradation of MTBE, that is selected with regard to proximity to the natural pH and using lowest catalyst loading, shown in Table 4 and the effect of the independents variable on the desirability shown in Figure 7.

Effect of Initial pH

pH is one of the most crucial parameters in photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants. Figure 7b and c show the percent of degradation efficiency for several initial pH conditions. The degradation efficiency increases as the pH value is incremented from 5 to 7 and then adversely decreases with the increased value of pH from 7 to 9. The pH of the solution has complex effects on the photocatalytic oxidation reaction. However, in general, the pH effect depends on the type of pollutant and zero point charge (ZPC) of semiconductor (catalyst) in the oxidation process. Because, the pH of the solution affects the electrostatic force between the catalyst surface and the pollutant. Interactions among the semiconductor surface, solvent molecules, substrate and charged radicals formed during the reaction, the interpretation of the effect of pH on obtained results from photocatalytic degradation cannot be expressed as a whole and this phenomenon should be tested in the laboratory for each type of pollutant or should be found through available references at desired operating conditions[19].

The phenomenon can be explained in terms of the zero point charge location (isoelectric point) of the Fe3O4/ZnO. In acidic pH, MTBE will be protonized to carry the positive charge while the surface of Fe3O4/ZnO is electropositive. Therefore, the acidic pH does not favor the adsorption of MTBE on the Fe3O4/ZnO particles. When pH is alkaline, MTBE is neutral, but the surface of Fe3O4/ZnO is electronegative. Hence, adsorption of MTBE on the Fe3O4/ZnO particles in alkaline pH was less than that in neutral pH. According to results obtained from Figure 7b and c, natural pH was the best pH value for degradation of MTBE in this study[10].

Effect of Fe3O4/ZnO MNPs concentration

The percentage of degradation efficiency against catalyst loading is shown in Figure 7a for several initial Fe3O4/ZnO nanoparticles’ concentrations. The percentage of degradation efficiency increases along the increase in the catalyst loading from 1 to 2.5 g/L. However, by an increase in excess of 2.5 g/L, this percentage declines. It should be noted that, these results are highly contingent on the maintained experimental condition. As the amount of catalyst increases, the number of adsorbed photons and molecules increases as well due to an increase in the number of Fe3O4/ZnO nanoparticles. As a consequence, the particle density within the illumination area increases. This behavior can be attributed to the increase in opacity, which gives rise to a reduction in the radiation passage through the reactor[20]. It may also lead to Fe3O4/ZnO aggregation, reducing the active points on its surface to adsorb organic compounds and UV, thereby reducing the quantity of e-h+ and OH free radicals and affecting the degradation, accordingly[21]. After reusing of magnetic particles, a small decrease in the photocatalytic activity observed. After 4 times, the removal percentage decreased to about 70 percent. This decrease can be due to fouling of light-insensitive materials on active pores or loss of particles (Figure 8).

Effect of initial MTBE concentration

Increase of initial MTBE concentration reduces its degradation as shown in Figure 7a and c. Similar results have been reported on the photocatalytic oxidation of other organic compounds interface[6–21]. At low MTBE concentrations, a larger number of water molecules will be adsorbed onto the available Fe3O4/ZnO nanoparticles, producing hydroxyl radicals and leading to a rapid oxidation process. On the other hand, at high MTBE concentration, there is a smaller portion of water molecules to free active sites, since the number of active sites remains the same. Consequently, the competition between the MTBE concentration and water molecules on adsorption increases and leading to a decline in the degradation rate.

Kinetics of MTBE degradation

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood rate expression has been used to describe the relationship between the heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation rate and the initial pollutant concentration[22].

Experimental results in optimum condition (Figure 8) Indicated that the photodegradation rate of MTBE with UV/Fe3O4/ZnO/H2O2 fitted the Langmuir-Hinshelwood (L-H) kinetics model as follows:

It is assumed that the photodegradation of MTBE follows a first-order reaction; therefore the above equation can be simplified to an apparent first-order equation:

where Kr is the reaction rate constant (mg/l.min), Ke is the adsorption coefficient of the MTBE (l/mg) and Kapp is the apparent pseudo-first-order constant that is the multiplication product of the adsorption constant and the reaction constant. In this study, a reasonable agreement (R2 = 0.96) was obtained between the experimental results and the linear form of the L-H expression. Furthermore, this expression used values of 0.033(1/min) for Kapp.

Effect of hydroxyl peroxide addition

Electron–hole recombination is the main energy-wasting step in the photocatalytic reaction. The prevention of this recombination is achieved by adding a proper electron donor or an acceptor to the system. Usually, molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide are used as electron acceptors in heterogeneous photocatalyzed reactions[23]. H2O2 can generate hydroxyl radicals through two ways as follows:

The results are presented in Figure 7b show that the degradation rate had a maximum of the [H2O2]/[MTBE] molar ratio of 5. However, higher concentration of H2O2 can have a negative effect. This may be due to the formation of HO2o, a species that is significantly less reactive than HOo[24]. As shown in equations 7 and 8, the excess H2O2 molecules on the catalyst surface may also act as powerful scavengers of radicals[25, 26].

Conclusions

In this study, Fe3O4/ZnO nanoparticles were successfully synthesized with average crystal size of 11.2 mm by precipitation method. Synthesized nanoparticles then utilized as a catalyst for the photocatalytic degradation of MTBE. The optimum levels of the operational parameters under the related constraint conditions were found at pH of 7.02, Fe3O4/ZnO MNPs concentration of 1.78 g/L, initial MTBE concentration of 89.14 mg/L, and [H2O2]/[MTBE] molar ratio of 2.33. In addition, according to the Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetic model, the apparent pseudo-first-order constant was 0.033 (1/min) for experimental results under optimum conditions. Also the recycling and reuse of MNPs was significantly successful.

Abbreviations

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- VSM:

-

Vibration sample magnetometer

- RSM:

-

Response surface modeling

- MNP’s:

-

Magnetic nanoparticles

- GAC:

-

Granular activated carbon

- OFAT:

-

Optimizing one factor at a time

- GC:

-

Gas chromatography

- HID:

-

Helium ionization detector

- AVOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- ZPC:

-

Zero point charge

- AOP’s:

-

Advanced oxidation processes.

References

MTBE health and safety: USEPA: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water. 1997. EPA-822-f-97–009

Rosell M: Analysis occurrence and fate of MTBE in the aquatic environment over the past decade. TrAC Trends Anal Chem 2006, 25: 1016–1029. 10.1016/j.trac.2006.06.011

Hu Q, Zhang C, Wang Z, Chen Y, Mao K, Zhang X, Xiong Y, Zhu M: Photodegradation of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) by UV/H 2 O 2 and UV/TiO 2 . J Hazard Mater 2008, 154: 795–803. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.10.118

Pontius FW: New horizons in federal regulation. J Am Water Works Assoc 1998, 90: 38–50.

Kuburovic N, Todorovic M, Raicevic V: Removal of methyl tertiary butyl ether from wastewaters using photolytic. Photocatalytic and microbiological degradation processes, Desalination 2007, 213: 123–128.

Eslami A, Nasseri S: Photocatalytic degradation of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) in contaminated water by ZnO nanoparticles. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 2008, 83: 1447–1453. 10.1002/jctb.1919

Safari M, Nikazar M, Dadvar M: Photocatalytic degradation of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) by Fe-TiO2 nanoparticles. J Ind Eng Chem 2013, 19: 1697–1702. 10.1016/j.jiec.2013.02.008

Cater SR, Dussert BW, Megonnell N: Reducing the threat of MTBE-contaminated groundwater. Pollut Eng 2000, 32: 36–39.

Araña J, Peña Alonso A, Doña Rodríguez JM, Herrera Melián JA, González Díaz O, Pérez Peña J: Comparative study of MTBE photocatalytic degradation with TiO 2 and Cu-TiO 2 . Appl Catal B 2008, 78: 355–363. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.09.023

Xu XR, Li HB, Gu JD: Simultaneous decontamination of hexavalent chromiu and methyl tert-butyl ether by UV/TiO 2 process. Chemosphere 2006, 63: 254–260. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.07.062

Tonga T, Zhanga J, Tiana B, Chena F, Heb D: Preparation of Fe3+-doped TiO 2 catalysts by controlled hydrolysis of titanium alkoxide and study on their Photocatalyticactivity for methyl orange degradation. J Hazard Mater 2008, 155: 572–579. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.11.106

Sahoo C, Gupta AK: Optimization of photocatalytic degradation of methyl blue using silver ion doped titanium dioxide by combination of experimental design and response surface approach. J Hazard Mater 2012, 215–216: 302–310.

Chung YS, Park SB, Kang DW: Magnetically separable titania-coated nickel ferrite photocatalyst. Mater Chem Phys 2004, 86: 375–381. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2004.03.027

Kurinobu S, Tsurusaki K, Naturi Y, Kimata M, Hasegawa M: Decomposition of pollutants in wastewater using magnetic photocatalyst particles. J Magnsm Magtc Mat 2007, 310: e1025-e1027. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.11.072

Waston S, Beydoun D, Amal R: Synthesis of a novel magnetic photocatalyst by direct deposition of nanosized TiO2 crystals onto a magnetic core. J Photochem Photobio A: Chem 2002, 148: 303–313. 10.1016/S1010-6030(02)00057-6

Hong RY, Zhang SZ, Di GQ, Li HZ, Zheng Y, Ding J, Wei DG: Preparation, characterization and application of Fe 3 O 4 /ZnO core/shell magnetic nanoparticles. Mat Res Bull 2008, 43(8):2457–2468.

Zhang J, Fu D, Xu Y, Liu C: Optimization of parameters on Photocatalytic degradation of chloramphenicol using TiO2 photocatalyst by response surface methodology. J Environ Sci 2010, 22(8):1281–1289. 10.1016/S1001-0742(09)60251-5

Kousha M, Daneshvar E, Dopeikar H, Taghavi D, Bhatnagar A: Box–Behnken design optimization of Acid Black 1 dye bio sorption by different brown macro algae. Chem Eng J 2012, 179: 158–168.

Mrowetz M, Selli E: Photocatalytic degradation of formic and benzoic acids and hydrogen peroxid evolution in TiO2 and ZnO water suspension. J Photochem Photobiol A 2006, 180: 15–22. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2005.09.009

Nikazar M, Gholivand K, Mahanpoor K: Photocatalytic degradation of azo dye Acid Red 114 in water with TiO2 supported on clinoptilolite as a catalyst. Desalination 2008, 219: 293–300. 10.1016/j.desal.2007.02.035

Carcia JC, Tankashima K: Photocatalylic degradation of imazaquin in an aqueous suspension of titanium dioxide. J Photochem Photobiol A: Chemistry 2003, 155: 215–222. 10.1016/S1010-6030(02)00370-2

Evgenidou E, Fytianos K, Poulios I: Photocatalytic oxidation of dimethoate in aqueous solutions. J Photochem Photobiol A 2005, 175: 29–38. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2005.04.021

Taffarel SR, Lansarin MA, Moro CC: The styrene photocatalytic degradation reaction kinetics. J Braz Chem Soc 2011, 22: 1872–1879. 10.1590/S0103-50532011001000007

Senthilkumaar S, Porkodi K: Heterogeneous photocatalytic decomposition of crystal violet in UV-illuminated sol–gel derived nanocrystalline TiO2 suspensions. J Colloid Interface Sci 2005, 288: 184–189. 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.02.066

Konstantinou IK, Albanis TA: TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous solution: kinetic and mechanistic investigations A review. Appl Catal 2004, B49: 14.

Galindo C, Jacques P, Kalt A: Photooxidation of the phenylazonaphthol AO20 on TIO2: Kinetic and mechanistic investigations. Chemosphere 2001, 45: 997–1005. 10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00118-7

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep gratitude to Professor Manouchehr Nikazar our research supervisor, for his patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and useful critiques of this research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MS and MHR designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper; MA designed and performed experiments; AA and SAAN performed the experiments and prepared the final manuscript; RA designed the kinetic model, revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Safari, M., Rostami, M.H., Alizadeh, M. et al. Response surface analysis of photocatalytic degradation of methyl tert-butyl ether by core/shell Fe3O4/ZnO nanoparticles. J Environ Health Sci Engineer 12, 1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-336X-12-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-336X-12-1