Abstract

Knowledge of the difficulties, costs, and territorial issues surrounding fishing communities seems crucial to achieve sustainable development goals in marine and coastal zones. However, such knowledge is not always available, sufficient, or even identifiable. The seabob-shrimp small-scale fisheries in the shallow waters of the State of São Paulo, in Southeastern Brazil, plays an important role in coastal livelihoods, providing social and economic benefits for a number of local communities and a premium source of regional seafood. Around 4000 fish-workers produce supplies for restaurants, fishmongers and supermarkets in coastal towns with about 2 million inhabitants. Nevertheless, harbor and naval mooring, the construction of pipelines, sewage disposal, controversial seasonal closures, and marine spatial zoning have all restricted the activity. A territorial approach is here proposed to examine the timeline of vertically implemented laws/regulations that may have resulted in a decrease of territories formerly available to that fisheries, accompanied by a comprehensive outlook of the overall policy context. The shrinkage of fishing territories has been evidenced and the kind of territorial loss detected does not seem to be implicit in cost analysis of fisheries, ecosystem services, or compensation. Top-down policies and a misunderstanding of environmental mitigation programs appear to have been contributing to increasing conflicts, mining multi-stakeholder processes and social justice in contrast to the ascendant economic growth of both the oil and gas and port industries. While economic and political pressures seem to shape current fishing territories, the recognition of the diversity of interests and power asymmetries in coastal zones directs our attention to a vital, often ignored, dimension of social reality. Institutional challenges and recommendations, such as territorial use rights and legal innovations are discussed, adding value to the self-organization of local communities for an effective process of balanced power both within and outside legal marine protected areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the aspects to be considered in the efforts to enhance stewardship in small-scale fisheries, is the sector’s situation in face of the expansion of multiple pressures in coastal zones (Allison et al. 2012; Elliot 2013). Within a multiple-use, common property resource system, not only each extractive and non-extractive use but also the system’s ability to support combined uses should be assessed (Edwards and Stein 1996). Moreover, the context of struggles over access to, and control of resources and space that often emerge from institutional and power inequalities (McCay and Acheson 1987) should not be ignored.

However, there is a clear gap in evaluating the processes and policies that deal specifically with the position of fishing communities in the midst of multiple-use coastal trade-offs, and their related power asymmetries (Huseman et al. 1987; Oekerson 1986). It is unclear whether this is due to the unpopularity of fishing activities among neoliberal environmentally-friendly sectors (Kopnina, 2015), but it seems evident that the reality of small-scale fishers is often invisible to, or disregarded by, both policy makers and the civil society (Gasalla and Tutui 2006; Petersen et al. 2005).

Knowledge on the struggles, costs, and territorial losses of fishing communities seems crucial to fill this gap and achieve sustainable development goals in coastal zones. Furthermore, it is particularly important to the strengthening of environmental stewardship roles and rights at the local level. Nevertheless, this knowledge is not always clear, available, or even identified (Gasalla et al. 2010).

Additionally, it may be difficult to define fishing territories and get them formally recognized by governments, largely due to their volatile physical boundaries, but also because of the increasing competing economic interests for the appropriation of aquatic spaces, land value and real estate in the world’s coastal and riverside areas (McNamara et al. 2015). It makes the identification of and claims for formal recognizion of fishing territories challenging. These factors may also explain why the real loss or reduction of fishing territories has been poorly documented and why there is a lack of global and regional estimates of their magnitude.

In this paper, we offer an analysis of the territorial marine loss faced by small-scale seabob shrimp fishers off the coast of São Paulo over recent decades, in order to reveal some of the processes behind the current threats to traditional fishing territories along Brazil’s coastline.

The seabob-shrimp small-scale fisheries in São Paulo

The Brazilian State of São Paulo is the country’s most populated and urbanized area, with around 43 million inhabitants, and therefore, comprises the largest domestic consumer market (IBGE 2013). The seabob shrimp fishery industry along its coast (Fig. 1) shows major regional socio-economic relevance among local fisheries (Mendonça et al. 2013). It contributes to the livelihoods of a number of low-income coastal communities, providing social and economic benefits as well as a premium source of regional seafood for the general population. Around 4000 fish workers and their families rely on the seabob shrimp fisheries, who supply the product to restaurants, fishmongers and supermarkets in several coastal cities with a combined population of two million (IBGE 2013). The seabob shrimp is a key ingredient in the regional cuisine, providing the base of typical recipes and snacks such as “peixe ao molho” (fish in shrimp sauce), “pastel” (fried filo-pastry pocket), “empadinha” (mini pie), and a low price option among local shrimp varieties.

However, only recently has that fisheries been recognized as the main source of shrimp in São Paulo, following an increase in the coverage of statistics on fisheries’ catch data (Mendonça et al. 2013). During the period 2000–2011 it was estimated the seabob shrimp fishery has increased at least ten-fold since 2008. In contrast to what had previously been thought as a predominantly industrial sector, Mendonça et al. (2013) reported that about 75 % of the seabob shrimp fishermen are engaged in small-scale activities responsible for more than 50 % of fishery production in the state. In terms of the fleet, 85 % of the fishing vessels are also classified as small-scale.

The emergence of the seabob-shrimp fishers in São Paulo is quite heterogeneous, ranging from small, traditional, coastal communities (“caiçaras”) to more recent entries (Lopes et al. 2009). The latter category mainly comprises of families coming from Southern Brazil (that originally worked as shrimp trawlers), and secondarily, of migrants from the Northeast region of the country that settled in mangrove areas similar to their birthplace. Although some parts of the coast in São Paulo are fairly urbanized (e.g., Guaruja) with a certain influx of fishers to traditional areas, those families seem to rely mostly on the sea to get their animal protein (Lopes et al. 2009). The latest settling of seabob shrimp fishers was reported as being due to invitations from relatives, which also indicates that there is no sign of a declining stock, since the returns from the most recent fishing trips suggests a perception of productivity remaining high (Lopes 2008). Families are the basic unit of production and they are totally dependent on shrimp. Shrimp processing plants, that are usually informal businesses, dominate the local economies (Gasalla et al. 2014a; Ykuta and Gasalla, 2014).

The evolution of the seabob shrimp fisheries over the last decade shows an increasing trend in terms of both catch volumes and fishing effort (Fig. 2). This allowed quite a stable annual catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE), which reached average values of 10 kg per fishing-hour between 2005 and 2007. Although statistical data and human perceptions suggest optimism in relation to the stock, the sector faces several threats in terms of economic viability and performance (Gasalla et al., 2010; 2014b; Souza et al. 2009a). Access rights seem to be decreasing but possible maritime territorial losses have never been estimated before.

Fishing effort (dashed line) and catch (in tons, grey line) of the seabob shrimp small-scale fisheries along the coast of São Paulo from 2000–2011 (adapted from Mendonça et al. 2013)

Within this context, the present study aimed to evaluate whether the seabob shrimp fishery in São Paulo has suffered any territorial loss and which mechanisms could possibly be underpinning the issue in terms of investment and policy considerations.

A territorial approach to estimating fishing losses

The assessment and management of marine resources is an increasingly spatial affair, meaning that area-based methods are among modern fishery management practices. Impact analyses of energy and industrial offshore developments primarily focus on spatial displacement and access to place-based resources, whilst marine protected areas (MPAs) are widely seen as a key resource management tool (St. Martin 2001; St. Martin & Hall-Arber 2008; Gasalla 2011). On the other hand, notions of fishing territories at the local level, both formal and informal, exclusive and shared, have received considerable attention and reporting all over the world (Kalland 1999). Fishing territories can be short-term, with temporary territorial rights (Forman 1970) or territorial claims (Cordell 1977), or more permanent, such as when a corporation publicly endorses rights to sea space as an estate.

The term ‘territory’ is used to designate a portion of nature or space that is claimed by a given section of society, aiming to guarantee rights of access to control and use all or part of the resources found there (Godelier 1979; Kalland 1999). A territorial approach may represent a social group whose members act as a legal individual in terms of collective rights to property, and have collective responsibility or other common interests (Keesing 1976). Thus, a territory is more a result of local and regional power than a mere jurisditional definition (Acheson 1979; Gottmann 1973; Raffestin 1993). Sack (1986) adds a flexible and dynamic temporal dimension to the concept, highlighting the notion that human behavior is influenced by the control of access in a particular territory. The term is also applicable to the notions of (1) governance (interaction and regulation between the actors, institutions, and State); (2) social coordination or coordination of the interest groups that takes place in a determined area (Santos 1999); and (3) development (Sabourin 2002).

In Brazil, territory is also seen and understood, from the perspective of rural development and family-based agriculture, as being the new unit of reference and measurement of the State’s actions (Schneider and Peyré-Tartaruga 2004). Similarly, considering what could be called a ‘maritime rurality’ of the caiçara communities (Diegues and Moreira 2001), the concept of territory adopted here represents “a space determined by power relationships where the boundaries are sometimes evident (easy to determine) but sometimes not explicit (not manifested), and have the use of space, coexistence, and the co-presence of each person and their activity, as well as the establishment of their relationships as references”.

In order to provide a territorial approach to the small-scale seabob shrimp fisheries, an estimate of the fishing area losses was undertaken. Such investigation was limited to an analysis of the formally restricted access to those particular fisheries, although other activities that have not yet been documented scientifically or legally exist in both land and sea areas, suggesting additional conflict of use.

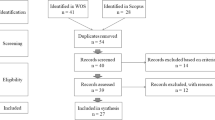

The policy analysis was based on a compilation and examination of laws and regulations that have been affecting the seabob-shrimp small-scale fisheries in São Paulo. The norms that had restricted fishing access were brought together in a GIS database resulting in shape files (SHP) (Fig. 3). The identified areas were uploaded to Google Earth Pro, and their sum was spatially referenced in hectares (ha). This allowed for an area-based estimate to be used as a reference for exploring a territorial approach aimed at identifying “non-apparent” fishing losses. This was followed by the total restriction estimate in relation to formerly available areas, based on the total maritime area stratified per isobaths (30, 20, 15 m depth) and divided by the area of total territorial lost.

An example of the maps generated by the territorial approach, derived from shape files (left) with all technical information from each different set of data (right). Original database is in Portuguese, picture shows original files on trawling restrictions in a particular estuarine region, illustrating the process of area-based estimate

The policy analysis was complemented by a comprehensive review of the management system, state of the resource, and interacting norms. This also took into account conflicts and competition between different interests located in history and social systems, including the interactions promoted or sanctioned by central government authorities (McCay and Acheson, 1987),

Policies driving fishing territories loss

Several policies resulted in spatial restricions to the seabob shrimp fisheries in São Paulo, although they were not necessarily implemented to reduce fishing impacts on the ecosystem. In Table 1, the multiple factors affecting fishing territories were classified according to the level of government intervention and policy sector, i.e. fishing-related regulations, MPAs, coastal zoning, naval activity, and norms due to infrastructure works (enterprise-related no-fishing zones), and the corresponding areas are shown.

In general, Federal-based regulations appeared to be more diverse, ranging from corporations’ exclusive zones, marine protected areas (MPAs), and “other fisheries” regulations. The State level regulations fell into two main categories: coastal zoning (ecological-economic zoning established by a formal plan) and marine environmental protection areas (APA) (Table 1). Most of the regulations found are not sea-bob shrimp fisheries-specific, although they do all affect it. In terms of the norms deriving from infrastructure activities, the definition of “dredged material disposal areas” (Santos harbor) has been shared by both Federal and State agencies, which was not the case with fisheries-related regulations.

Overall, the São Paulo State Economic Ecological Zoning Plan was responsible for more than a half (66 %) of all the area-based restrictions that were imposed over a period of almost 50 years (Table 1). Morever, along the São Paulo coastal zone, multiple corporations had legal right to occupy marine areas and to control exclusive zones around their boundaries where fishing is prohibited (13 % of restricted areas).

The MPAs recognized as being restrictive to the seabob-fisheries in São Paulo were found to originate from both Federal and State levels and were defined as ‘no-take’ areas. The other set of fishing regulations that was found arose from both the Federal level and from zoning plans at State level (Table 1).

On the whole, since 1967, the State of São Paulo has imposed several area-restrictions with 27 norms increasing quantitatively over time in terms of the total restricted area. Restricted area has progressively increased and intensified between 2000–2014 (Fig. 4). Currently these restrictions amount to about 15 % of the entire coastal area of São Paulo state up to the 15 m isobath, 10 % of the 25 m isobaths, and 3 % of the 30 m isobathic area.

Considering the percentage of fishing restrictions in the different depth zones in relation to the whole fishing area previously used by seabob shrimp vessels (from 3 to 30 meters in depth), it appears that the shallower the water, the greater the impact of the policies has been in terms of territorial loss. Therefore, the smaller the scale of the fisheries, the more restrictive the outcome has been.

The fishing area historically operated by the seabob-shrimp fishery is shown in Fig. 5. The dynamics of the maritime territorial transformation in the region can be understood by taking into account the location of “restriction zones” implemented in each decade (Fig. 5). The total loss of fishing territories was estimated to add up to more than 64,000 hectares (Table 1), currently evidencing a correlation between the restriction of fishing areas and the loss of fishing territories as understood by the fishers.

Location of the historical seabob-shrimp fishing zone off the cost of São Paulo and areas restricted to its fishery across decades (1: 1970s; 2: 1980s; 3: 1990s; 4: 2000s; 5: 2010s). Triangles are infrastructure projects, polygons and the coastal white zones are no-take areas, and the dots indicate (low resolution) closed areas

Discussion

The expansion of large-scale industries within fishing territories and the ecological deterioration of the water have triggered heated disputes between enterprises, fishing communities, and the state (Camargo 2014). This study reveals an estimate of the fishing territories formerly available to the seabob-shrimp fisheries that have been reduced as a result of access restrictions due to several distinct reasons beyond conservation. It also reveals a not often recognized state role that imposes restrictions on the small-scale fisheries sector but seems to offer no counterpart of any kind whatsover for the directly or indirectly decrease in income. The analysis has been limited to the territorial aspect, i.e. the formal area-restrictions imposed on fishing itself. Thus, if environmental health problems that also generate economic losses for fishing communities such as the quality of seawater and seabed (CETESB 2005) are taken into account, the potential impact on fishing territories (or other marine ecosystem service) can be much larger.

Human activities in natural systems that shares common resources (i.e. common pool resources or CPRs) often face two key dilemmas: (a) the ‘exclusion problem’ (i.e. the exclusion of potential users or the control of access is difficult), and (b) the ‘subtractability problem’, (i.e. each user is capable of subtracting from the welfare of all the others) (Feeny et al. 1990, Ostrom 1990). In Brazil, the sea and its resources are public assets regulated by the Federal government (Federal Constitution 1988, Art.20). The right to fish is often shared among users divided into different sectors according to licensing criteria defined by national agencies. Access to a fishing area, however, depends on other sea-based activities. The multiple activities that make use of marine areas can be divided into those that depend on the health of the ecosystem and those that are not related to ecological integrity. The former category includes the small-scale fisheries, aquaculture, and sports-related nautical activities as well as non-fishing activities such as community-based tourism, the small-scale hotel sector, agricultural activities, and restaurants serving sea products. The latter group includes several infrastructure projects that require and occupy the competing maritime space for “industrial logistics” such as ports, oil and gas, traffic, disposal of sewage/run-off, seabed extraction and materials dredged from harbors (Elliot 2013).

Among the several trade-offs in coastal management, we should highlight two important issues: 1) the limits of alterations that can be supported in such a way that the development of activities that rely on healthy marine ecosystems may be maintained and allowed; and 2) how far contemporary society can neglect a renewable-based economy (which, if well managed, can be sustained for an indefinite period of time) to the detriment of a market-oriented logic that compromises ecosystem services and depends on external factors and motivations far beyond local communities’ desires. These dilemmas are clearly observed in the case of the small-scale seabob shrimp fisheries in São Paulo. While both government and civil society make efforts to organize themselves to discuss which institutional arrangement might be best placed to address the tradeoffs abovementioned, the persistence of the invisibility of fishing territorial loss limits the accountability of the economic and environmental policies in generating additional costs for fishing communities, and therefore the development of new policies able to correct this burden.

The reduction of the fishing territories of the seabob shrimp fisheries in São Paulo over the last 50 years were identified as originating from two main factors: 1) the top-down environmental policies, including the creation of MPAs and regulations for other fisheries; and 2) the environmental concession process for the building of enterprise/corporations infrastructures within the coastal zone.

With regards to the former, the process for the foundation of both protected areas and fishing regulations in São Paulo involved very little community participation until 2008, and conflicts with fishing communities were widely reported (Diegues 1973, 1996). Selected participation has taken place since 2002, but only in the State’s coastal management zoning plan with the fisheries sector not being well represented. Some defense arguments were however eventually presented by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), but they represented to less that 5 % of the management councils composition. The creation of the ‘Marine APA’ (a category of State-level MPA) is relatively recent (2008) which does not play a role in the regulation of the seabob-shrimp fishing but has potential for the development of participative mechanisms if well implemented. In some other developing countries, for example in Southern Pacific states, “locally-managed marine areas” have proven to result in a successful effort for spatial management based upon de facto communities’ participation and agreement (Govan, 2009).

With regard to the territorial losses for fishing due to enterprises and infrastructure, it should be noted that in Brazil an environmental impact assessment is required in order to approve an environmental license (CONAMA Resolution 01/86). However, increasing impact in coastal zones has been heavily criticized in recent decades since the growth of business and infrastructure has occurred faster than that of environmental legislation (Ab´Saber 2001). Although some assessments have attempted to evaluate the impact on fishing areas, in reality, fishing territories have been affected and reduced, and mitigation and compensation mechanisms have been worthless or weakly instituted with insufficient fishers’ participation.

This study reveals that the smaller the fishing boat, the more impact it will have felt from public policies (see section 2). This conclusion raises a serious issue concerning equity and social justice. Small-scale fishers have less fishing power as they cannot go beyond exclusion zones, resulting in higher vulnerability to the current regulations that have resulted in about 15 % of territorial loss. Such vulnerability may be seen as a drawback on sustainable development goals (SDGs) and human rights (SDSN 2015). Justice is an important condition for governability, increasing the overall capacity for governance of any societal entity or system (Kooiman 2008; Jentoft 2013). Under injustice, stakeholders are likely to revolt against government efforts to sustain the resource or promoting sustainable development (Jentoft 2013). This also reinforces the view that power and authority are central issues in the analysis.

Fisheries assessment overview: the seabob shrimp stock and its current management

In the study area, there are still controversies over the size of seabob-shrimp populations, as well as over spawning and recruitment seasons. The species is distributed over a wide geographical area and different research groups along Brazil’s coastline have reached different conclusions, somehow reflecting the nature of the species which seems to be biogeographically diverse. There is currently a closure season (March-May) in compliance with a legal norm (IBAMA, 2008) that covers the Southern region from Espírito Santo to Rio Grande do Sul States. However, this geographical area is considered excessively large and, according to genetic studies, it comprises more than one different stock/population (Gusmão et al. 2006, 2013; Franscisco 2009, Piergiorge et al. 2014). Moreover, the closure season was originally established rather to protect the pink-shrimp (Farfantepenaus paulensis, F. brasiliensis) from the estuaries to the ocean (D'Incao 1991). However, in São Paulo, pink-shrimp is less abundant in the estuaries and seabob shrimp’s dominates the coastal zone (Graça-Lopes et al. 1997). Therefore, the time frame currently stipulated by the legislation is also controversial since the current closing period was developed for another shrimp stock with different behavior and population patterns. In fact, Heckler et al. (2013) show the existence of two main periods of female maturation, suggesting that closure for the seabob-shrimp should be brought forward if protection of the spawning season is desired. In terms of the recruitment period, Severino Rodrigues et al. (1992) reported that recruitment of the seabob-shrimp starts as of the species’ 20th or 30th month of life and fishery catches contain a considerable amount of young individuals. Notably, adults and juveniles of the stock share areas of equal depth, and the high variability of recruits in the shallow water, resulting from meteo-oceanographic dynamics coupled with the larval survival period, seems to complicate recruitment estimates, while environmental variability might strongly affect stock abundance.

Souza et al. (2009b) report the fishers’ frustration towards the continuous changes in the regulations, and highlight the need for further extension work. There seems to be a feeling of betrayal within the sector, since the State creates regulations that are different to those agreed upon at numerous meetings with representatives. Although Azevedo (2013) reminds us that the review of the closure season was fullfilled as part of a participative process, the regulation (IBAMA 2008, IN 189/2008) did not seem to meet the wishes of either the fishers or the scientific sectors in terms of regionalizing and adjusting the closure to a more appropriate geographical scale. All these factors appear to contribute to an erosion and mistrust of the current fishing regulation process. Apart from the disputes, the management of this fishery seems to have remained static and dated, and is certainly in need of reform.

Despite all the problems, the seabob shrimp stock’s CPUE has remained reasonably stable over the last decade, suggesting that overfishing is not in place at least for the target species (Mendonça et al. 2013; Kolling and Avila-da-Silva 2014). A minimum revenue of R$3.00 per kilogram caught by the small-scale fleet was reported as an average in 2008 (Souza et al. 2009a). More recent economic assessments (2012–2014) showed a much higher price variation for the seabob shrimp, suggesting that under extreme conditions of small shrimp catches, the price may vary by up to 500 % during a single year (Gasalla et al. 2014b).

From the perspective of its gastronomic value, the seabob shrimp seems irreplaceable in several of Brazil’s most popular dishes. Even in low quantities (such as in 2014), it may acquire a special economic value. Such a substantial price increase would move the seabob shrimp from its traditional category as a “cheap shrimp” to the position of an “irreplaceable shrimp”. The gastronomic value and demand is no less important than the biological aspects since its new “status” may increase the small-scale fishers’ bargaining power - as an important asset - in the whole coastal management process. Despite the difficulties faced because of the value-chain with a low rate of revenue for the fishers and the lack of collective or public infrastructure (i.e. anchorage piers, refrigeration chambers, subsidized fuel, and small, locally-based shipyards), these fisheries are labor intensive in comparison to other coastal seasonal activities or those that rely on a constant turnover of personnel.

However, participatory approaches may still be considered as being very poor and inefficient. Recently, an oil accident in the Santos Harbor, leading to economic loss for fishers, revealed difficulties in estimating local fisheries yields within the impacted area, constraining fishers to negotiate compensation (Gandini, 2014). The process has been dragged into the courts, which could be avoided should communities have access to, and control of, fisheries information, which seems likely only through participative monitoring (FAO, 1998).

Ways forward

Considering the current fisheries scenario, we argue that community-based participatory monitoring and management could be potentially decisive in preventing the process of reduction of fishing territories that also seem important to seafood supply. In addition to this, we intend to highlight and explore two of the main developments related to the major factors identified by the territorial approach: (i) the territorial use rights for fisheries and a new way of handling fishing communities under coastal MPA regimes; and (ii) the legal innovation for conciliatory dialogue regarding the impacts felt from private enterprises.

Territorial use rights for fisheries and Marine Protected Areas

Notions of exclusive fishing territories at the local level have received much attention worldwide (e.g. Japan, France, New Zealand, and North and South America). The concept of territory as an area occupied more or less exclusively by an individual or group by means of repulsion through over-defense, or some form of communication, has been tested by ecological models. For example, several authors found correlation between ecological factors and the existence of fishing territories using cost-benefit models developed to analyze territoriality. Dyson-Hudson and Smith (1978), who employ an ecological model to discuss the existence of territories among hunters-gatherers and pastoralists, suggest that territories only exist where the costs involved in defending them are considerably less than the rewards. This fact should help to understand the (non-) territorial nature of fisheries in general.

However, an a priori recognition of the existence of fishing territories in certain situations would be a more efficient means of limiting fishing efforts (Kalland, 1999). With smaller territories people are in a better position to influence the resource base on which their future rests, whether the territories are formally recognized and supported by the state or not. Community-controlled territories enhance the efficiency of sanctions, not least because activities at sea cannot be isolated from those on land. Open access seems beneficial only to the more powerful fishers who, with large, efficient vessels, can fish one area after another, and fishing regulations have widely been more of a response to exclusive territories than to the ecological factors theselves (Kalland 1996, 1999).

Mainly because of this, governance over common goods and services has often been transferred from governments to civil society in several fishing area-based cases. For example, Kurien et al. (2006) reported the legal aspects and the social organization process of the aquarian reform (re-territorialization) that has been underway in Cambodia since the beginning of the last decade, as part of which state properties started being regulated locally, resulting in better community access and usufruct rights. In the South Pacific, both the network of “locally-managed marine areas” (LMMAs) in western island states (Govan, 2009), and territorial use rights for fisheries (TURFs) in Chile (Gelcich et al. 2012), have been encouraging fishers to increase their governance powers. Although TURFs cannot be seen as a panacea for solving all fisheries’ governance problems, (showing, as they do, constraints beyond the management of benthic resources - Aburto et al. 2014), the concept shows a potential for the context of seabob shrimp fisheries in São Paulo, especially under and within local MPAs.

In 2008, following a quite controversial process, the State of São Paulo created a continuum of three APAs where fishing is allowed (Dias and Máximo 2010). However, both the APAs and the coastal fisheries are still threatened by non-fishing impacts such as pollution, oil, sewage disposal, the construction of infrastructure and the effects of large scale tourism. Moreover, progress with respect to the fisheries in these areas has been dismal, even though fishers’ knowledge has been well-evidenced as being extremely useful for ecosystem-based fisheries management on the Northern coast (Leite and Gasalla 2013).

Overall, the major weakness in the coastal and fisheries management models found by the present analysis is that they mainly rely upon command-and-control mechanisms, with the adoption of static measures with limited mechanisms for adaptation or updating in the short-term. This has created a great deal of discomfort in the sector. The fishers’ distrust in the current bureaucratic management system (e.g. establishment of a closure season different from that agreed upon), the harsh and oppressive manner in which these measures are applied by the State, and the loss of fishing territories that have been found, emphasize the serious need for a series of reforms (Table 2).

Firstly, the current fora instituted under the MPAs (APA) management councils could be optimized in a way that promotes a review of the current marine plan under the State’s Ecological Economic Zoning (ZEE) as well as the seabob closure season at a more regional level. A new direction to protect the environment and establish territorial use rights for fishers based on genuine and consistent community-based processes at the local level would be recommended. Also, although some MPAs have evidenced real benefits for biodiversity conservation in coral reef ecosystems, it should be mentioned that São Paulo’s APAs have a very particular coastal setting and social structure (e.g. a non-reef ecosystems, located in a large portion of the country’s coastal zone with stronger social-environmental disputes and economic power which has been gathering public attention due to recent oil and pre-salt discoveries). In this sense, their approach to natural resource management should instead be inspired by other MPA categories within the Brazilian legal framework (SNUC 2000) more appropriated to the socioenvironmental context, such as the Marine Extractive Reserves (RESEX) and Sustainable Development Reserves (RDS) (e.g. see Gasalla 2011).

Lastly, it has been demonstrated that spatially-oriented community-based measures such as TURFs (Panayoutou 1982) or LMMAs could be of particular help in contributing to an increase in the sustainability of fisheries, ecosystem stewardship, and local social wellbeing. If both the food production rights and poverty alleviation needs are recognized in territorial approaches, new ways of governability may advocate for participatory processes (Gasalla 2011; FAO 2014) that should be characterized by transparency, accountability, cohesiveness, and inclusiveness (Jentoft 2013).

Enterprises and legal innovation for public policies

Coastal zone infrastructure projects demand marine space for their activities, using it as logistics channels and an area for deposits, imposing ‘subtractability’ on fishing areas and excluding other incompatible activities. For example, underwater dredging, sewage and the limitations on the access imposed by port activities and by the oil and gas sector may indirectly create offsets for small-scale fishers. In Guanabara Bay, in Rio de Janeiro, 75 % of the whole artisanal fishing area has been lost to oil and gas, ports, and infrastructure construction (Chaves 2011). These projects as a whole, often financed by public resources, fall into the accepted practices of environmental licensing that, as a rule, lead to socio-environmental damage, which is hard to equate within the licensing procedure. In the so-called “green economy” paradigm, it should lead to financial compensation and reimbursements in the process of valuing biodiversity as part of business or market values. In Brazil, entrepreneurs are required by law to develop programs for the “socio-environmental compensation” of each of their different projects in order to maintain their environmental licenses. However, these programs are created or designed from the entrepreneurs’ perspective with no input from those who suffer the consequent damages. Characterized by a major conflict of interests between those who need the compensation, those who have to pay for it, and those who usually implement the process, a reformulation of such procedures has been recommended (Gasalla 2011). Further analysis suggests that more independent social-environmental programs based on specific territorial use rights, funded and paid for by the enterprise responsible for the loss of fishing territory, and which include non-monetary compensation for the fishing communities, may be an important way forward.

Furthermore, there is a clear opportunity for social innovation (e.g. projects based upon communities’ demands) amongst governmental environmental agencies, since it is a public attribution to consider and accept proposals from third parties (e.g. fishing communities). This is something that is already happening, as can be seen in the case of the mangrove areas around Santos Harbour (CETESB 2012).

Another innovation presently under way in Brazil, which is developing in the legal Federal sphere, involves the judiciary’s understanding of “mediation” as a method for bringing interests together. A legal development should occur with the approval of the Mediation Law, a new piece of legislation which requires that a negotiation between conflicting parties be part of procedural rites so that environmental injustices are solved extra-judicially based on conciliatory dialogue (Gandini 2014). It is expected that this sort of legal innovation, applied in the social-ecological field, will be a landmark in the field of disputes over spatial use in Brazil and will certainly benefit by a territorial approach to fishing.

In summary, the ways forward embrace the need for a more in-depth territorial approach to fisheries, especially from the perspectives of present coastal zoning, MPAs and the blue-economy. It should include effective participation, the recognition of fishing territories, and innovative processes for environmental licensing, adaptation, mitigation, and compensation. Such participatory approach to fishing (re)territorialization seems to move towards the nationwide mobilizations led by the 'Movimento de Pescadores e Pescadoras’ (‘Fishermen’s and Fisherwomen’s Movement’ - MPP) which defends a Brazilian version of territorial use rights as a way to deliver societal benefits and achieve ecological and socio-economic goals in fisheries (MPP, 2012). This also shows a certain amount of agreement with what was proposed by the Citizenship Territories Policy (‘Programa Territórios de Cidadania’) in Brazil in around 2008, which failed to get implemented in the fisheries and aquaculture sector.

Concluding remarks

Fishing activities in the seawaters of the State of São Paulo have been restricted by different policies associated with the installation of specific businesses and aims that go beyond habitat conservation. Despite this, an estimate of the affected (compared to the potential) areas likely to be used by the small-scale fisheries has not previously been conducted.

An examination of non-explicit territories and the related inequalities has assisted this analysis by directing attention to the relevant, but sometimes ignored, social dimension of fisheries in coastal zones. This study has shown that around 15 % of the potential fishing areas of the seabob shrimp has now limited or prohibited entry due to the implementation of a set of coastal zoning policies, and port, oil and gas, and infrastructure projects. These types of zoning goals are considered to be legitimate by the different interest groups, including conservation, but nevertheless mitigation and compensation mechanisms for the small-scale fisheries sector are either weak, undirected, or even non-existent. The kind of territorial loss detected does not seem implicit in a cost-analysis of fisheries and ecosystem services. Fishers’ territorial losses amount to more than 64 thousand hectares over time, which took place mostly in the last 15 years.

A more in-depth understanding of the small-scale fisheries sector’s real position in multi-goal coastal zone management seems essential in order to enhance its eventual ecosystem stewardship role. The issues revealed here have been discussed within the context of overall policy while a set of recommendations and envisioned directions was presented. A reorientation of investments starting with the country’s infrastructure projects leading to innovation in compensation mechanisms and novel environmental mediation methods, an evolution from command-and-control instruments to participative approaches, and the definition of territorial use rights for fisheries were highlighted.

Public interests seem integral to property regimes, and power plays in the distribution of benefits account for institutional change. The facts raised here seem to encourage small-scale fishers to become important players in the coastal zone and fisheries management scenarios. As long as fishing territories are seen, recognized, and granted, a maritime ‘rurality’, even in more urbanized areas, shows the potential to grant high quality protein in the food production system and to collaborate in both poverty alleviation and the green-economy. It would now be expected that the development of local, territorial approaches and legal innovation in public policies should become a new focus in natural resource and coastal management in Brazil, where “compassionate conservation” (sensu Kopnina, 2015) and the recognition of fishing territories can take place.

Our findings might also contribute as “food for thought” in the analysis of the equity and power relationship within coastal policies and conservation goals, the concession of use rights for traditional communities, and on the progressive loss of fishing territories elsewhere.

References

Ab´Saber, A.N. 2001. Litoral do Brasil/Brazilian coast. (English version C. Holmquist), 286. São Paulo: Metalivros.

Aburto, J.A., W.B. Stotz, and G. Cundill. 2014. Social-ecological collapse: TURF Governance in the context of highly variable resources in Chile. Ecology and Society 19(1): 211.

Acheson, J.M. 1979. Variations in traditional inshore fishing rights in Maine lobstering communities. In North Atlantic Maritime Cultures, ed. R. Andersen, 253–276. The Hague: Mouton.

Allison, E.H., B.D. Ratner, B. Asgard, R. Willmann, R. Pomeroy, and J. Kurien. 2012. Rights Based Governance: from fishing rights to human rights. Fish and Fisheries 13: 14–29.

Azevedo, V. 2013. Sustentabilidade da pesca direcionada ao camarão-sete-barbas, Xiphopenaeus kroyeri (Heller, 1862), no Litoral Norte do Estado de São Paulo, 118. São Paulo: PhD Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto Oceanográfico.

Camargo, A. 2014. The Crisis of Small-Scale Fishing in Latin America. NACLA, North American Congress on Latin America. online: https://nacla.org/news/2014/8/8/crisis-small-scale-fishing-latin-america. Accessed June 2014.

CETESB. 2005. Relatório das águas litorâneas do estado de São Paulo, 389. São Paulo: Série Relatórios, Secretaria de Estado do Meio Ambiente.

CETESB. 2012. Companhia de Tecnologia de Saneamento Ambiental. Secretaria Estadual de Meio Ambiente.Parecer técnico n 236/12/IE de 06/07/12. Processo 268/2010, 74. Santos: Ampliação do Terminal Marítimo da Ultrafértil.

Chaves, C.R. 2011. Mapeamento participativo da pesca artesanal da Baía de Guanabara. Rio de Janeiro: Dissertação (Mestrado em Geografia) – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Centro de Ciências Matemáticas e da Natureza, Instituto de Geociências.

Cordell, J. 1977. Carrying capacity analysis of fixed territorial fishing. Ethnology 17(10): 1–24.

Dias, H., and N. Máximo. 2010. Conservação Marinha e Ordenamento Pesqueiro. Conselho Nacional da Reserva da Mata Atlântica. 40 Série Conservação e Áreas Protegidas, 61.

Diegues, A.C.S. 1973. Pesca e Marginalização no Litoral Paulista. 1973. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências Sociais) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Sociais. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo.

Diegues, A.C.S. 1996. O mito moderno da natureza intocada, 169. São Paulo (Brasil): HUCITEC.

Diegues, A.C.S., and A.C.C. Moreira. 2001. Espaços e recursos naturais de uso comum. São Paulo: NUPAUB – USP.

D'Incao, F. 1991. Pesca e biologia de Penaeus paulensis na Lagoa dos Patos, RS, Brasil. Atlântica, 13: 159–169.

Dyson-Hudson, R., and E.A. Smith. 1978. Human territoriality: an ecological assessment. American Anthropologist 80(1): 21–42.

Edwards, V.M., and N.A. Stein. 1996. Developing an analytical framework for multiple use commons. 6th Annual Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property, Voices from the Commons. Berkeley: University of California.

Elliot, M. 2013. The 10-tenets for integrated, successful and sustainable marine management. Marine Pollution Bulletin 74: 1–5.

FAO. 1998. Food and Agriculture Organization, UN. Participatory analysis, monitoring and evaluation for fishing communities: A manual. FAO Fisheries Technical Papers, 364.142.

FAO. 2014. Food and Agriculture Organization, UN. Resumed session of the technical consultation on international guidelines on securing sustainable small-scale fisheries. Rome, Italy: FAO (TC-SSF/2014-2). 23p.

Feeny, D., B.J. McCay, and J.M. Acheson. 1990. The tragedy of the commons: Twenty-two years later. Human Ecology 18: 1–19.

Forman, S. 1970. The raft fishermen: tradition and change in the Brazilian peasant economy, 158. Bloomington, Indiana: University Press for International Affairs.

Franscisco, A.K. 2009. Caracterização genética populacional do camarão marinho Xiphopenaeus kroyeri no litoral sudeste-sul do Brasil. Dissertação de mestrado, 100. São Carlos: Universidade Federal de São Carlos.

Gandini, F. 2014. Por uma nova ética para a governança ambiental. Valor Econômico 11(A16): 2.

Gasalla, M.A. 2011. Do all answers lie within the community? Fishing rights and marine conservation 185–203. In World Small-Scale Fisheries Contemporary Visions, ed. R. Chuenpadgee. The Netherlands: Eburon.

Gasalla, M.A., and S.L.S. Tutui. 2006. “Fishing for responses”: a local experts consultation approach on the Brazilian sardine fishery sustainability. Journal of Coastal Research 39: 1294–1298.

Gasalla, M.A., A.R. Rodrigues, L.F.A. Duarte, and R.U. Sumaila. 2010. A comparative multi-fleet analysis of socio-economic indicators for fishery management in SE Brazil. Progress in Oceanography 87: 304–319.

Gasalla, M.A., P.R. Abdallah, A.R. Rodrigues. 2014. Avaliação da viabilidade socioeconômica das frotas pesqueiras comerciais que atuam na região Sudeste e Sul do Brasil por meio de indicadores de desempenho. Research Project Report CNPq/MPA - N ° 42/2012.

Gasalla, M.A., A.R. Rodrigues, F. Gandini, A. Pelegrinelli, M.V. Santos, and P.R. Abdallah. 2014b. How costly if presently to fish in the South Brazil Large Marine Ecosystem? Common-property resources and fishing industry viability. Bergen: IMBER Open Science Meeting.

Gelcich, S., M. Fernández, N. Godoy, A. Canepa, L. Prado, and J.C. Castilla. 2012. Territorial use rights for fisheries as ancillary instruments for marine coastal conservation in Chile. Conservation Biology 26(6): 1005–1015.

Godelier. 1979. Territory and property in primitive society. In Human Ethology. Cambridge: University Press.

Gottmann, J. 1973. The significance of territory. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia.

Govan, H. 2009. Achieving the potential of locally managed marine areas in the South Pacific. SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin, 25.

Graça-Lopes, R., E.P. Santos, E. Severino-Rodrigues, F.M. de Souza Braga, and A. Pussi. 1997. Aporte aos conhecimento da biologia e e pesca do camarão sete-barbas ( Xyphopenaeus kroyeri HELLER, 1862) no litoral do Estado de São Paulo. B. Inst. Pesca, São Paulo 33(1): 63–84.

Gusmão, J., Lazoski, Monteiro, Solé-Cava. 2006. Cryptic species and population structuring of the Atlantic and Pacific seabob shrimp species, Xiphopenaeus kroyeri and X. riveti. Marine Biology 149: 491– 502.

Gusmão, J., R.M. Piergiorge, and C. Tavares. 2013. The contribution of genetics in the study of the seabob shrimp populations from the brazilian coast. Bol. Inst. Pesca, São Paulo 39(3): 323–338.

Heckler, G.S., S.M. Simões, M. Lopes, F.J. Zara, and R.C. Costa. 2013. Biologia populacional e reprodutiva do camarão sete-barbas na Baía de Santos, São Paulo. Bol. Inst. Pesca, São Paulo 39(3): 283–297.

Huseman, R.C., J.D. Hatfield, and E.W. Miles. 1987. A new perspective on equity theory: the equity sensitivity construct. The Academy of Management Review 12(2): 222–234.

IBAMA. 2008. Instituto Brasileiro de Meio Ambiente. IN 189/2008.. http://www.ibama.gov.br. Accessed June 2014.

IBAMA. 2010. Instituto Brasileiro de Meio Ambiente. Nota Técnica CGPEG/DILIC/IBAMA n° 01/10. Programas de Educação Ambiental. Diretrizes para a elaboração, execução e divulgação dos programas de educação ambiental desenvolvidos regionalmente, nos processos de licenciamento ambiental dos empreendimentos marítimos de exploração e produção de petróleo e gás. (http://www.ibama.gov.br). Accessed June 2014.

IBGE. 2013. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística.. www.ibge.gov.br. Accessed in June 2014.

Jentoft, S. 2013. Social justice in the context of fisheries. A governability challenge. In Governability of Fisheries and Aquaculture: theory and applications, eds. Bavinck, Maarten, Ratana Chuenpagdee, Svein Jentoft and Jan Kooiman, 382. MARE Publication Series 7: Springer.

Kalland, A. 1996. Marine management in Japan. In Fisheries management in crisis, ed. K. Crean and D. Synes, 71–83. Oxford: Fishing news books.

Kalland, A. 1999. Mare closum as a management tool in fishing societies. In Tenure and sustainable use, ed. J.A.E. Oglethorpe, 182. Cambridge UK: IUCN Gland Switzertland.

Keesing, R.M. 1976. Cultural anthropology. A contemporary perspective. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Wintston.

Kolling, J.A., and A.O. Avila-da-Silva. 2014. Evaluation of determinants of Xiphopenaeus kroyeri (Heller, 1862) catch abundance along a Southwest Atlantic subtropical shelf. ICES Journal of Marine Sciences 71(7): 1793–1804.

Kopnina, H. 2015. Revisiting the Lorax complex: deep ecology and biophilia in cross-cultural perspective. Environmental Sociology 1(4): 315–324.

Kooiman. 2008. Exploring the concept of governability. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis 10(2): 171–190.

Kurien, J., S. Nam, N. Onn, and S.O. Mao. 2006. Cambodia’s Aquarian Reforms: The Emerging Challenges for Policy and Research, 32. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Inland Fisheries Research and Development Institute.

Leite, M.C.F., and M.A. Gasalla. 2013. A method for assessing fishers’ ecological knowledge as a practical tool for ecosystem-based fisheries management: Seeking consensus in Southeastern Brazil. Fisheries Research 145: 43–53.

Lopes, P.F.M. 2008. Modelos ecológicos e processos de decisão entre pescadores artesanais do Guarujá, SP, 108. Sao Paulo State: University of Campinas.

Lopes, P.F.M., R. Silvano, and A. Begossi. 2009. Artisanal commercial fisheries at the southern coast of São Paulo State, Brazil: ecological, social and economic structures. Interciencia 34: 536–542.

McCay, B.J., and J.M. Acheson. 1987. The Question of the Commons. The Culture and Ecology of Communal Resources. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

McNamara, D.E., S. Gopalakrishnan, M.D. Smith, and A.B. Murray. 2015. Climate adaptation and policy-induced inflation of coastal property value. PLoS ONE 10(3): e0121278. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121278.

Mendonça, J., R. Graça-Lopes, and V.G. Azevedo. 2013. Estudo da CPUE da pesca paulista dirigida ao camarão-sete-barbas (Xiphopenaeus kroyeri) entre 2000 e 2011. Bol. do Inst. de Pesca. 39(3): 251–261.

MPP. 2012. Movimento Pescadores e Pescadoras. Iniciativa Popular para estabelecimento de territórios pesqueiros no Brasil.. http://peloterritoriopesqueiro.blogspot.com.br. Accessed 15 May 2014.

Oekerson, R.J. 1986. A model for the analysis of common property problems. In Proceedings of the Conference on Common Property Resource Management. National Research Council, 13–30. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Panayoutou, T. 1982. Territorial Use Rights In Fisheries. In Preparation for the FAO World Conference on Fisheries Management and Development, FAO held a Workshop on Territorial Use Rights in Fisheries (TURFs), in Rome during 6–9 December 1982. Faculty of Economics. Bangkok 9, Thailand: Kasetsart University.

Petersen, C., N. Jaffer, and J. Sunde. 2005. Making Local Communities Visible: MPAs in South Africa. Samudra 937:36-40.

Piergiorge, R., M. Pontes, A. Duarte, and J. Gusmão. 2014. Haplotype-specific single-locus multiplex PCR assay for molecular identification of sea-bob shrimp, Xiphopenaeus kroyeri (Heller, 1862), cryptic species from the Southwest Atlantic using a DNA pooling strategy for simultaneous identification of multiple samples. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 54: 348–353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bse.2014.03.023.

Raffestin, C. 1993. Por uma geografia do poder. São Paulo: Ática.

Sabourin, E. 2002. Desenvolvimento rural e abordagem territorial: conceitos, estratégias, atores. In Planejamento e Desenvolvimento dos Territórios Rurais: conceitos, controvérsias e experiências, ed. E. Sabourin and O. Teixeira. Brasília: EMBRAPA Informação Tecnológica.

Sack, R. 1986. Human territoriality: its theory and history. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Santos, M. 1999. A natureza do espaço - espaço e tempo: razão e emoção, 3rd ed. São Paulo: Hucitec.

São Paulo State Map Data Bank. (http://sigam.cloudapp.net/sigam2/Default.aspx?idPagina=13231). Access 15 May 2014.

Schneider, S., and I.G. Peyré-Tartaruga. 2004. Território e abordagem territorial: das referências cognitivas aos aportes aplicados à análise dos processos sociais rurais. Raízes 23(1–2): 99–116.

SDSN. 2015. Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Getting Started with the Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations.

Severino Rodrigues, E., R. Graça-Lopes, J.A.P. Coelho, and A. Puzzi. 1992. Aspectos biológicos e pesqueiros de camarão sete-barbas (Xiphopenaeus kroyeri) capturado pela pesca artesanal no litoral do Estado de São Paulo. B. Inst. Pesca, São Paulo 19(único): 67–81.

SMA. 2008. São Paulo State Environmental Agency. – Oficial website of Marine Protected Areas of São Paulo. http://fflorestal.sp.gov.br/unidades-de-conservacao/apas-marinhas. Acess 12 June 2014.

Souza, K., L.M. Casarini, M.B. Henriques, C.A. Arfelli, and R. Graça Lopes. 2009a. Viabilidade econômica da pesca de camarão sete-barbas com embarcação de pequeno porte na praia do Perequê, Guarujá, Estado de São Paulo. Informações Econômicas 39(4): 8.

Souza, K., N. Rodrigues da Silva, R. Graça-Lopes, and C.A. Arfelli. 2009b. Análise da política pública do defeso do camarão-sete-barbas (Xiphopenaeus kroyeri) na comunidade pesqueira do Perequê (Guarujá, São Paulo, Brasil). Leopoldianum – Revista de Estudos e Comunicações da Universidade Católica de Santos 97: 61–71.

SNUC. 2000. Protected Area National System. Brazilian Government.

St. Martin, K. 2001. Making space for community resource management in fisheries. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 91(1): 122–142.

St. Martin, K., and M. Hall-Arber. 2008. The missing layer: Geo-technologies, communities, and implications for marine spatial planning. Marine Policy 32: 779–786.

Ykuta, C., and M.A. Gasalla. 2014. Value chains of small-scale fisheries: a comparative investigation in the coastal region of São Paulo, Brazil. In Procedings of the 2nd World Small Scale Fisheries Congress, Merida.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially funded by the Brazilian National Research Council - CNPq (Project 42/2012 on fisheries socioeconomic viability). We would like to thank the research grant for MAG and the fellowship provided to FG (DTI-B). We thank Amanda Rodrigues and Felippe Postuma from the Fisheries Ecosystems Laboratory in São Paulo, for their help, respectively with CNPq project and preparation of maps. We also owe special thanks to Ms. Isadora Parada and colleagues from the Environmental Agency of São Paulo for sharing the database, to the Fishing Territories Committee (Brazilian Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture 2009–2011), and the Guarujá Fisheries Department. The manuscript improved considerably after suggestions provided by Dr. Fabio de Castro and two anonymous reviewers. We are also grateful to the University of São Paulo’s Oceanographic Institute and the ‘Too Big To Ignore’ (TBTI) global research partnership which provided us with the opportunity to connect with other fishing territories elsewhere.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gasalla, M.A., Gandini, F.C. The loss of fishing territories in coastal areas: the case of seabob-shrimp small-scale fisheries in São Paulo, Brazil. Maritime Studies 15, 9 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40152-016-0044-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40152-016-0044-2