Framing Climate Change: Economics, Ideology, and Uncertainty in American News Media Content From 1988 to 2014

- 1Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 2Department of Political Science, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada

- 3Department of Political Science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

The news media play an influential role in shaping public attitudes on a wide range of issues—climate change included. As climate change has risen in salience, the average American is much more likely to be exposed to news coverage now than in the past. Yet, we don't have a clear understanding of how the content of this news coverage has changed over time, despite likely playing an important part in fostering or inhibiting public support and engagement in climate action. In this paper we use a combination of automated and manual content analysis of the most influential media sources in the U.S. -the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and the Associated Press- to illustrate the prevalence of different frames in the news coverage of climate change and their dynamics over time from the start of the climate change debate in 1988. Specifically, we focus on three types of frames, based on previous research: economic costs and benefits associated with climate mitigation, appeals to conservative and free market values and principles, and uncertainties and risk surrounding climate change. We find that many of the frames found to reduce people's propensity to support and engage in climate action have been on the decline in the mainstream media, such as frames emphasizing potential economic harms of climate mitigation policy or uncertainty. At the same time, frames conducive to such engagement by the general public have been on the rise, such as those highlighting economic benefits of climate action. News content is also more likely now than in the past to use language emphasizing risk and danger, and to use the present tense. To the extent that media framing plays an important role in fostering climate action in the public, these are welcome developments.

Introduction

News media shape public attitudes on a variety of topics, and climate change is no different. Commentators attribute much of the blame for Republican climate denial to conservative news outlets like Fox News,1 which have been found to disseminate misinformation on climate science.2 However, Fox News represents only a small part of the news media environment, more important is the content of climate change news content in widely consumed mainstream news outlets. Although it has been the subject of a large amount of research, we do not have a good sense of how this content has changed over time.

Science communicators understand the importance of the news media. Of particular interest has been how climate change is framed in public discourse. Communicators have a choice of which considerations to emphasize and which to downplay on any given political issue and they make such decisions strategically. The choices they make are the issue frames that proliferate in political discourse. This is even truer with a complex topic like climate change. It is an issue that involves multiple complex domains, like science, economics, and value considerations, trade-offs, unequal impacts within society and across nations, and future projections about somewhat uncertain consequences. This complexity provides journalists, parties, and interest groups tremendous latitude in framing the issue to serve their interests and beliefs. The news media play a seminal role in this process because they are often the primary source of information on complex political issues for the average citizen. They are therefore the primary mode of delivery of issue frames to the public.

Frames related to climate change can emphasize economic costs or benefits, heighten partisan or ideological conflict, emphasize or downplay scientific uncertainty, among other things. There are likely implications for the public's support for climate action and willingness to act on these attitudes in a variety of ways—from voting for environmentally-friendly candidates to engaging in personal action to reduce one's own carbon footprint or even engaging in political activism. If the frames citizens encounter lead citizens to think of climate science as uncertain or mitigation as being costly, or see climate change as an ideological battleground, we might expect their propensity to support and engage in climate action to vary accordingly (Bain et al., 2016; Hornsey and Fielding, 2016; Walker et al., 2018).

A growing body of experimental research has explored how different frames in climate communication can affect attitudes and behavior. Alongside this important work has been research that examines the prevalence of frames in political discourse (Boykoff and Boykoff, 2004, 2007; Antilla, 2005; Boykoff, 2007; Hoffman, 2011; Painter and Ashe, 2012; McGaurr et al., 2013; Painter, 2013; Painter and Gavin, 2016; Feldman et al., 2017). These works have shed light on the nature of climate change coverage in the United States and in other countries. However, their use of manual coding limits the degree to which they can reliably observe changes in the prevalence of important frames over a long time period and across different news outlets. This is where our main contribution lies.3 This paper aims to systematically analyze the content of the climate change news stories in the most popular news media outlets in the United States as climate change emerged as a national issue. Specifically, we examine three key features of coverage identified in the literature to influence public attitudes on climate change: uncertainty and risk surrounding climate change (Morton et al., 2011), economic costs and benefits of mitigation policies (Brulle et al., 2012), and appeals to conservative ideology (Dixon et al., 2017).

Framing Climate Change

Framing is an essential concept in communication studies and has been a subject of interdisciplinary research for several decades. It refers to “the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an issue” (Chong and Druckman, 2007, p. 102). The process of framing involves two key ingredients: selection and salience. Framing is then about selecting some key aspects of the perceived reality and making them more salient in the process of communication (Entman, 1993). Those receiving that message have their own unique conceptualizations of issues—often called “frames in thought”—which are influenced by “frames in communication” or considerations that are advanced by speech acts or written work (Chong and Druckman, 2007). The influence of the latter on the former can be seen as a framing effect.

Scholars have exhibited framing effects with surveys, experiments, and qualitative case studies across a wide range of issues including support for government spending, campaign finance, affirmative action, evaluations of foreign nations, and many others (see Chong and Druckman, 2007 for an extensive survey of the literature). However, issues that are most influenced by mediated communication tend to be complex ones that are mostly “invisible” to the public and, thus, difficult to comprehend for many (Schäfer and O'Neill, 2017).

Framing is unavoidable. All human knowledge makes use of frames, and every word is defined in relation to the frames it neurally activates (Lakoff, 2010). Moreover, since frames always come in systems, a single word can have the potential to activate not only its defining frame, but also much of the system its defining frame is in (Lakoff, 2010). Every issue, including climate change, can be viewed from a variety of different perspectives and understood as having consequences for multiple values or considerations. For those doing the communicating, the skillful use of framing can help them effectively convey their argument, frequently by emphasizing specific a specific set of considerations related to the issue at hand. The varying weights placed on these considerations often play a decisive role in determining overall attitudes and preferences (Druckman, 2001). The information environment, such as the news media, play an important role in this process as they frequently carry the specific messages from the elites to the mass public (for an example of how this works in the context of energy policy, see Clarke et al., 2015).

Economic Costs and Benefits

We focus on three classes of frames that we believe have particular relevance for societal debate on climate change, based on an analysis of relevant literature. First, frames in climate change news coverage can focus on the economic costs and benefits of climate action for individuals or the society writ large. Researchers have found that fluctuations in the state of the economy affect levels of environmental concern (Kahn and Kotchen, 2010). People are less likely to support climate change mitigation policies when the economy is underperforming (Elliott et al., 1997), and concern with climate change is correlated with higher levels of employment and income (Scruggs and Benegal, 2012; Carmichael et al., 2017).

The state of the economy is an objective fact, but the future projection of the possible consequences of climate mitigation policy for the economy is far more complex. As such, it is open to framing by political actors seeking to mobilize public support for their position. Economic concerns surrounding climate change can be framed in terms of their costs and benefits. Some work has shown that cost-framed messages are effective in influencing climate change attitudes and behaviors (Davis, 1995; Vries et al., 2016), while framing climate mitigation in terms of possible benefits increases support for climate action, even more so than pointing out the costs of inaction (Spence and Pidgeon, 2010).

Party elite behavior has adjusted accordingly (Nisbet, 2009). Republicans have typically adopted frames to highlight the potentially detrimental economic costs of climate action, like increased energy costs or the impact on the US's global competitiveness, to mobilize public opposition to mitigation. Democrats, for their part, have tended to emphasize the benefits of investing in renewable energy sources and their potential to revitalize the economy (Nisbet, 2009). This has been particularly true since President Obama's push for green jobs with the economic stimulus advanced in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

The relative balance of these frames in news content may have implications for the willingness of the public to support and engage in climate action (Bain et al., 2016; Hornsey and Fielding, 2016; Walker et al., 2018). As corporate America has gradually transitioned between intransigence on greenhouse gas emission reductions to cooperation, it is possible this balance has changed over time. No work has systematically examined this possibility in news content.4 We do so here.

Conservative and Free-Market Ideology

Second, frames may be present in the news media that present climate change mitigation through the lens of left-right ideological conflict. Ideology and values matter in shaping citizen attitudes toward climate action. Anchored in a rich literature on motivated reasoning in social psychology (Kunda, 1990; Ditto and Lopez, 1992), cultural cognition theory posits that individual risk perceptions—and the acknowledgment of expert consensus—are shaped by their values in ways to maintain their group identities (Kahan, 2013). Those with individualistic value predispositions are expected to be more skeptical of environmental risks because they justify regulation and government intervention (Kahan et al., 2011). Kahan and his colleagues highlight several mechanisms of cultural cognition: the selective recall of supportive expert opinion, the selective imputation of knowledge and trust to sympathetic experts, and the biased search of information and assimilation of expert messages. Along a similar line, Campbell and Kay (2014) argue that solution aversion is key to understanding conservative reticence to accept climate science. Policy solutions to combating climate change are threatening to the ideological identities of conservatives, which biases the perception and interpretation of information from experts. Consequently, they find, along with other scholars, that emphasizing market-friendly solutions to mitigation can lower conservative resistance to climate science (Campbell and Kay, 2014; Dixon et al., 2017).

One important limitation of ideological and values-based explanations for conservative resistance to climate change is that it takes this resistance as a fait accompli. However, it is not clear that this was the case. As late as 1997 Republicans were as likely as Democrats to see climate change as a serious problem (Krosnick et al., 2000). Citizens had to learn to connect their individualistic or conservative ideological beliefs to opposition to climate action. They could have done so with exposure to ideological frames and arguments in the news made by conservative and Republican elites. After all, the conservative movement has mobilized, more or less unanimously, to oppose climate change mitigation (Oreskes and Conway, 2011). To be sure, these groups have often used arguments related to economic costs of mitigation to undermine public support for climate action. They could have also used frames emphasizing the ideological threat of climate action, in the form of larger government, reduced American sovereignty, and sizable restrictions on free market competition. These themes tap into the individualism end of Kahan's individualism-communitarianism values dimension and conservative ideology more broadly.

A large literature on partisan cues in public opinion formation highlights the fact that political elites are often powerful drivers of public opinion (Downs, 1957; Zaller, 1992; Berinsky, 2009). Previous research has found that the news coverage of climate change has politicized over the past few decades (Merkley and Stecula, 2018) and that partisan cues can polarize the public on this issue (Tesler, 2018; Van Boven et al., 2018). What remains unknown, however, is the degree to which ideological frames and arguments are conveyed in the news media on climate change. These frames could have provoked the polarization of Americans above and beyond the effects of partisanship.

Uncertainty and Risk in Climate Change

A final set of important frames in climate news coverage involves the communication of uncertainty and risk in climate change. Scientific uncertainty exists when there is a lack of scientific knowledge or disagreement over the knowledge that exists at a given point in time (Friedman et al., 1999). Researchers understand that all forms of scientific endeavors involve such uncertainty. In the context of climate change, discussion of uncertainty can focus on conflicting claims or a lack of knowledge about the existence or cause of climate change, its present-day effects, and the difficulty with assessing probabilities of specific outcomes and their consequences in the future (Patt and Schrag, 2003; Renn et al., 2011). Journalists covering scientific issues, such as climate change, are also routinely confronted with uncertainty, since controversy and debate are important criteria for the “newsworthiness” of a story (Friedman et al., 1999). As a result, how journalists present and describe scientific uncertainty affects how the public interpret such uncertainty.

Communicating this uncertainty, however, is notoriously difficult (Fischhoff and Davis, 2014). Scientific discourse often involves an amount of details that can overwhelm even seasoned experts. It can also leave out crucial uncertainties that are commonly understood by the experts within the field, but need to be communicated to the broader public (Fischhoff and Davis, 2014). Finding the right balance is difficult, yet essential, considering the important role that uncertainty plays in human decision making (Curley et al., 1986; Sword-Daniels et al., 2018). Psychological research shows that uncertainty generally has a negative effect on prosocial behaviors, since it tends to enable people to adopt self-serving narratives about their actions and limit their capacity to cooperate in social dilemma situations (Hine and Gifford, 1991; Dannenberg et al., 2015; for a review of the literature, see Kappes et al., 2018).

Experimental work highlights that uncertainty framing also matters for climate change related behaviors, such as decreasing one's energy consumption (Morton et al., 2011). A focus on uncertainty in news coverage can potentially reduce the public's support and engagement in climate action because of the unclear outcomes of such actions.

Uncertainty can take several forms in climate change coverage. On a wide range of climate impacts and long-range forecasts of future warming there is uncertainty that is appropriately acknowledged by experts in the media's coverage of climate science. More problematic is if uncertainty is used in a way that casts doubt on the well-established tenants of the climate consensus of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—that climate change is happening, is predominantly man-made through the production of greenhouse gas emissions, and will result in severe environmental and human harm. The persuasive power of uncertainty in this context is its implicit justification and reification of the status quo, especially as it pertains to fossil-fuel usage and carbon emissions (Feygina et al., 2010).

One way in which this type uncertainty enters the media coverage of climate change has been through the journalistic engagement of so-called “false balance.” Reporters frequently treat topics as debates in which they present “both sides” in order to adhere to a journalistic norm of objectivity. This norm exists, in part, because both journalists and the general public prize it (Schudson, 1978; Giannoulis et al., 2010), but also because it acts as a mechanism to protect journalists from attacks on their credibility and to preserve access to sources on both sides of a given political debate (Hallin, 1989; Shoemaker and Reese, 2013). The desire for balance also serves the media's tendency toward drama and conflict in news coverage (Bennett, 2007).

In many contexts it is important for journalists to be fair and evenly balanced in their presentation of different sides of a story, but it quickly becomes awkward when discussing the existence or causes of climate change where the credibility of each side does not have equal weight. And, the consequences of this coverage are troubling. Presenting a scientific consensus as a debate confuses the public on the state of the science and, in the case of climate change, possibly reduces support for climate action (Friedman et al., 1999; Corbett and Durfee, 2004; Koehler, 2016; McCright et al., 2016).

Newsroom norms of objectivity will only contribute to a balanced presentation of a political debate if another side presents itself. Journalists ultimately rely on easily accessible sources when reporting on the news. And, because of the activism of the fossil fuel industry and conservative movement, there have been no shortage of sources ready and willing to use a platform provided by journalists to cast doubt on climate science—the so-called “Merchants of Doubt” (Oreskes and Conway, 2011). Scholars have noted that these groups have made a concerted effort to mobilize opposition to climate mitigation policy by undermining trust in foundations of climate science for both the public and policy makers (Jacques et al., 2008; Dunlap and McCright, 2011; Dunlap and Jacques, 2013; Farrell, 2016a,b). While these groups are likely not as active in the media as conventional wisdom might suggest (Merkley and Stecula, 2018), it is still possible that the press, and in particular conservative media, pick up on their message of uncertainty in their coverage of climate science even if they don't explicitly cite these actors.

As the broader research on misinformation has shown, various myths surrounding climate science, including those pertaining to certainty of different outcomes, tend to be “sticky,” and hence very difficult to correct (Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Efforts to correct such information tend to be ineffective, and, in some circumstances might even result in what is called a backfire effect, when people get more entrenched in their original position (Nyhan and Reifler, 2010; Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Some promising work suggests that exposing people to correct information prior to misinformation might be an effective way to “inoculate” them from the perils of misinformation, at least in some contexts, but the broader point remains that, if the press disseminates uncertainty frames about climate change, such information might play a negative role in people's attitudes about climate change and climate change mitigation policies (Cook et al., 2017; Jolley and Douglas, 2017).

The themes of uncertainty have been analyzed in the context of climate change news coverage. Some research has shown that coverage of climate change in the 1990s and early 2000s was characterized by scientific inaccuracy and uncertainty, which was driven by an adherence to balanced reporting and resistance to a growing body of scientific evidence. More recently, however, balance nearly disappeared from the press (Zehr, 2000; Boykoff and Boykoff, 2004, 2007; Boykoff, 2007). The scope of this work, however, has been fairly limited in terms of the time dimension as well as the amount of news coverage examined, as was highlighted in the previous section. However, scholars who have been examining this feature of news coverage of climate change in the comparative context, have highlighted that the U.S. coverage features substantially more climate skeptic voices pushing doubt about climate science, compared to countries like India or France (Painter and Ashe, 2012). Furthermore, contrary to the findings in the U.S.-centric literature, the authors found that skeptics voicing climate increased their media presence between 2007 and 2010 (Painter and Ashe, 2012). In a separate analysis, Painter (2013) also found that uncertainty was the second most common frame used in climate change coverage, appearing in 76 percent of American articles, however it was the salient frame in only 13 percent of the coverage. It is important to note that this analysis, however, was based only on a total of 55 articles. This disparity in findings highlights the need to systematically examine uncertainty in the context of American news coverage and examine degrees of uncertainty, not just whether the frame is present or not.

Related to the communication of scientific uncertainty is risk. Discussion of possible climate change impacts involve frames and language that convey the severity of possible climate impacts. As the science of climate change has evolved, it has become increasingly clear that risks of inaction are high (Oreskes, 2004; McMichael et al., 2006; IPCC, 2014). Importantly, the prospect of severe loss has been found to motivate people to engage in collective action in social dilemma situations (Milinski et al., 2008; Dannenberg et al., 2015; Farjam et al., 2018), but people tend to underestimate risks associated with climate change because they are abstract and mostly detached from their daily life (Weber, 2006; Rabinovich and Morton, 2012). Consequently, frames that focus on the dangers of climate change may motivate climate action in the general public.

Climate impacts, however, occur both in the distant future and at present. Accordingly, these risks can be framed either way. Scholars have noted that the public's propensity to support and engage in climate action may be conditioned by the degree to which they psychologically proximate to the effects of climate change (see McDonald et al., 2015 for a review). The most studied aspect of this has been spatial proximity. For example, Spence and Pidgeon (2010) find that framing climate impacts as locally relevant increases one's propensity to support climate mitigation. There is a temporal dimension as well. Nicolaij and Hendrickx (2003) demonstrate through experimental manipulation that increasing the temporal onset of climate change produces a reduced willingness to engage in climate action for about half of their participants. The reason why proximity, either temporal or spatial, might matter has to do with the fact that things that are psychologically close seem more tangible and important than those that are “farther” apart, as construal theory would suggest (Trope and Liberman, 2010). What we do not know, however, is how temporally proximate the presentation of climate change is in the major sources of information consumed by Americans.

These three, broad sets of frames: economic costs and benefits, appeals to conservative values, and uncertainty and risk in climate science all could play a role in shaping the public's support and engagement in climate action. However, little is known about how often these frames are featured in news content and how this may have changed over time. As a result, in the rest of this paper, we seek to answer the following research questions:

1. What is the balance of economic cost vs. economic benefits frames in climate change coverage, and did it change over time?

2. How prevalent were ideologically conservative appeals in the climate change coverage, and did they change over time?

3. How often do the news media cover climate change using uncertainty and risk frames, and did the prevalence of these frames change over time?

Data and Methods

We conducted a content analysis of prominent American news media outlets to learn more about how the news media frames climate change. We selected three top circulation daily newspapers with a large, and growing, online presence to get a representative view of the mainstream media coverage: the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post, as well as the newswire agency the Associated Press. We choose these newspapers since they are the highest circulation papers in the United States and this circulation has been increasing in recent years.5 Furthermore, they each enjoy a large online presence as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal are ranked as the 3rd, 7th, and 19th most popular news websites on the internet by Alexa, at the time of this writing.6 They have also been the focus of a vast amount of scholarly attention in communication literature, as they are widely considered to be agenda-setters for both the public and other news media sources (Golan, 2006; Zhang, 2018). The Associated Press, according to its annual report, is used by 900 newsrooms globally, and nearly half of the world's population sees their content on any given day.7 In short, these sources represent a significant portion of the mainstream news media landscape.

This selection of sources clearly does not include social media data, which, according to the data by the Pew Research Center, makes up an increasingly larger portion of Americans' media diets.8 Our main focus, however, is longitudinal, so we concentrate on the most influential print news sources that have covered the issue of climate change from the beginning. Furthermore, it is worth highlighting that most Americans continue to get their news from mainstream sources, even in the age of a highly fragmented media landscape. For example, recent analyses of actual behavior data, such as people's web browsing patterns, reveal that most people obtain their news from mainstream, centrist sources (Flaxman et al., 2016; Guess, 2016). That is not to say that the partisan sources and social media are irrelevant or that they might not be growing in prominence, but our focus in this project was on the influential mainstream sources that covered the issue of climate change from the emergence of the issue.

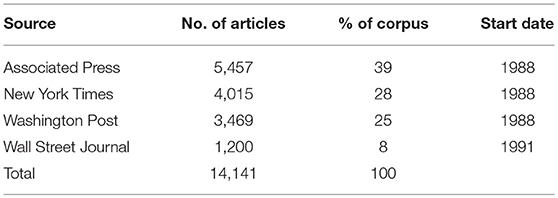

News articles were collected from Lexis Nexis and Factiva for the time period between 1988 and 2014. We start our analysis in 1988, the year of James Hansen's Congressional testimony, which the New York Times proclaimed to be the “Beginning of Global Warming.”9 Articles that mentioned climate change only in passing were excluded from the sample, to ensure that we examined only relevant news reports.10 In total, the corpus includes 14,141 stories. A detailed breakdown of news reports, by source, is featured in Table 1. The Associated Press makes up the bulk of the content, but the New York Times and the Washington Post also covered the issue extensively. The Wall Street Journal is an outlier, representing only 8 percent of the sample.

We rely primarily on automated approaches to content analysis in this paper, which allow for the full classification and measurement of entire populations of news articles across criteria we are interested in. These techniques are increasingly used by scholars in the social sciences to study news content and political discourse more broadly (Young and Soroka, 2012; Grimmer and Stewart, 2013; Lacy et al., 2015). They stand in contrast with human coding approaches, thus far dominant in climate change communication literature, that depend on the coding of much smaller random samples of articles. Human coding has its advantages. It can allow for a nuanced coding of content that takes fully into account the context in which words and language are used. However, the costs of this richness are efficiency and a lack of estimate precision across diverse sub-populations. Our aim in this paper is to provide estimates of the prevalence of frames in news content across sources and over a long period of time—tasks which are much more feasibly done with automated approaches to content analysis.

We use supervised machine learning to identify economic, conservative ideological, and uncertainty frames in coverage. The process first involves us (the researchers) hand coding a random samples of 2177 articles to train and test an algorithm.11 In this case we use Support Vector Machines (SVM), which is a supervised machine learning technique that plots data points on an n-dimensional space to find a hyperplane that best differentiates our classes of objects. We ensured our sample was stratified across three periods (1988–1996, 1997–2005, and 2006–2014) to ensure that our algorithm's performance would not fluctuate as climate change increased in salience over time.

We randomly divided our hand coded sets into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%). The former is used to train the algorithm, while the latter allows us to compare the machine's coding to our own. After training and testing the algorithms, they were used to classify the full corpus of articles for each of our frames.

We assess the reliability of our trained algorithms with three metrics. First, we compute a simple accuracy measure, which is the percent of our testing set with agreement between our human and machine coding. However, accuracy alone is not sufficient to judge the quality of a classifier. Algorithms may have poor predictive capacity but still yield high accuracy scores when classes are imbalanced by following a simple rule of assigning cases the value of the dominant class. Thus, we also present precision and recall scores for each algorithm. The former tells us how many of our selected items are relevant. This metric is used by those concerned with minimizing false positives. The latter tells us how many of our relevant items are actually selected—related to the minimization of false negatives. We present both because we want precision and recall to be approximately equal to present unbiased estimates of proportions. We don't want false negatives to outweigh false positives or vice versa. Note that these two metrics are typically used in the context of information retrieval where researchers are primarily interested in accurate predictions of instances of a class of objects—in this case our frames. Because we are interested in estimating proportions of articles of a given class we need to be interested in accurate predictions of both the presence and absence of our frames, so we take the average of precision and recall scores for both.

The above process was applied to train and test the algorithms related to each of our frames. The only difference between them was in the size of the hand coded training and testing set. Each of our frames is imbalanced in the hand coded set. There are more cases of each frame being absent than there are of instances of a frame being used. SVM, like other supervised machine learning approaches, is vulnerable when classes are imbalanced. In the process of training and testing our algorithms we found we could improve performance by training on a corpus where articles with a given frame command a larger share of the hand coded set. So, for each of our frames we randomly removed articles without a given frame such that those with the frame represented a third of the overall set. This reduced the number of overall articles in the combined hand coding set used for training and testing purposes as described below.

We now discuss each of our coding tasks in turn. First, we coded whether (1) or not (0) a news article had mention of possible costs of climate change mitigation to the economy. This could involve discussion of higher taxes, higher energy prices, reduced employment or economic growth, or reduced competitiveness vis-à-vis developing countries. We code these dimensions of economic cost together because they are often discussed together in news content, and, when not, typically involve the use of similar language and rhetoric. The reliable use of supervised machine learning requires the selection of topics that are clearly distinct in their language. In some cases substantial discussion was present in a given article about economic impacts, but in other cases such frames were present in short rhetorical passages from political elites, particularly Republicans. An example of the use of such a frame can be found in a New York Times article on December 13, 1997 where Republicans attacked the Kyoto Protocol:

“Republicans are already testing arguments…Jim Nicholson, the chairman of the Republican National Committee, said the pact will ‘radically change the American life style.’ And Audrey Mullen, the executive director of the conservative group Americans for Tax Reform, said, ‘Al Gore would prefer to stick working-class America with a big tax increase and stick America with lost jobs.”’

Second, we coded articles for whether (1) or not (0) they had references to economic benefits for climate change mitigation. These frames feature discussion of win-win features of some climate mitigation policies, like green jobs, lower energy and gas bills through increased energy efficiency, and increased profits for green-friendly corporations. Importantly, we coded these frames not to include reference to the costs of climate inaction. Discussion of energy efficiency, on its own, was also not enough to meet our criteria. There had to be mention of how such efficiency benefits consumers or companies in the long run. For example, this frame was used in a Wall Street Journal article on March 14, 2008 describing Wal-Mart's efforts to reduce its carbon footprint:

“The company is also looking into ways to reduce the amount of plastic used in making bottled-water containers, he said. The impetus for the company in doing all this isn't just to please environmentalists, he said, but to save money. ‘It really is about how you take cost out, which is waste,’ he said. ‘The savings by taking out wasted material helps keep prices low for Wal-Mart’s customers.' Indeed, Mr. Scott told reporters after his talk that the current economic slump is prodding Wal-Mart even more to undertake its waste-reduction program. ‘When is a better time?”’

We classified our full sample based on a training and testing set of 1,878 articles for economic cost frames, and 864 for economic benefit frames. Our economic cost classifier was 80% accurate, with an average recall and precision of 0.76 and 0.80 respectively, indicating good performance. Similarly, our economic benefit classifier was 80% accurate with average recall and precision scores of 0.74 and 0.78, respectively.

Third, we coded articles if there was any discussion related to conservative ideological themes (1) or not (0). Specifically, we were interested in arguments that stressed the need to oppose climate action because such policies empower bureaucrats, undermine American sovereignty, serve a “big government” agenda, redistribute wealth, increase regulation, restrict freedom, or violate the principles of the free market. Importantly, we wanted these arguments to be distinct from arguments about economic cost, and we excluded conservative frames that were used in support for climate action as their occurrence was too rare to reliably train an algorithm to engage in topic classification. This frame was used in the same New York Times story as above:

“Republicans are already testing arguments. Steve Forbes, a Republican Presidential contender, immediately called the accord ‘an unprecedented government seizure of American freedom and sovereignty.’ He added that ‘the Clinton health care plan pales in comparison.”’

More commonly, though, these themes were present in newspaper op-eds, such as the following from a Wall Street Journal op-ed on December 13, 2004:

“There's nothing capitalist about lobbying government to erect a program that serves no other purpose than the redistribution of wealth, whether it be from one company to another, or from consumers to corporations.”

We trained our algorithm on a combined training and testing set of 405 articles. Our classifier was 85% accurate, with average recall and precision scores of 0.70 and 0.80, respectively.

Finally, we coded each article for how balanced it was toward arguments of supporters and opponents of the IPCC consensus—that climate change is happening, manmade, and a serious problem. Articles were coded −1 if there was no presence of discussion in the article that cast uncertainty on the veracity of any part of the IPCC climate consensus. They were coded 0 if there was effectively an even balance of perspectives between those that support for IPCC consensus and those that reject it, and 1 if the article featured a complete rejection of the IPCC consensus and embrace of the uncertainty frame. This latter category primarily took the form of op-eds by climate skeptics. Articles were also coded as −0.5 and 0.5 if they featured both perspectives on climate science but were notably slanted in one direction or the other.

There were too few instances of articles scored 0 and below to train an algorithm to reliably return a fine grained measure of article balance, so we collapsed all categories above −1 when training our algorithm. Thus, articles could be scored as 1 if they had any discussion that cast doubt on the IPCC consensus and thus used an uncertainty frame, and 0 if they had no such discussion.

An example of the use of an uncertainty frame is found in a Washington Post article on October 30, 2000 citing a quote by, at the time, presidential candidate Texas governor George W. Bush:

“By contrast Gov. George Bush remains largely stuck in a posture of wait and see. He says he takes global warming seriously, and he has proposed mandatory controls on power plant emissions that would include caps on the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. But in the debate he said, ‘I don't think we know the solution to global warming yet. . . . Before we react I think it's best to have the full accounting, full understanding of what's taking place.”’

We trained our algorithm on combined training and testing set of 1,179 articles. Our classifier was 77% accurate, with average recall and precision scores of 0.70 and 0.68, respectively.

To examine the prevalence of language related to risk and time horizon, we turned to a different set of automated content analytic methods. Instead of supervised machine learning, we used dictionary methods. There were two primary reasons for this choice. First, the aspects of coverage discussed above were difficult to capture using a dictionary approach, and we weren't able to produce reliable results with the dictionaries that we inductively put together. Supervised machine learning approaches, however, did reliably work. Secondly, capturing simpler components of language, such as risk and tense, is much more straightforward with dictionary methods, especially with a pre-assembled and verified dictionaries included in Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) software (Tausczik and Pennebaker, 2010). The software has been used in countless studies in the fields of communication, political science, and computational linguistics, among others.

The LWIC dictionary is composed of 1,393 words measuring different linguistic dimensions. For our purposes here, we use two specific dictionaries embedded into LWIC: risk and present tense. The risk dictionary is a collection of words and phrases such as alarm, avoid, hazard, and threat, while present tense includes words like lives, now, or present. In general, research has shown that dictionary methods tend to do a good job capturing different linguistic dimensions of text, comparable to the performance of manual coding (Young and Soroka, 2012).

Results

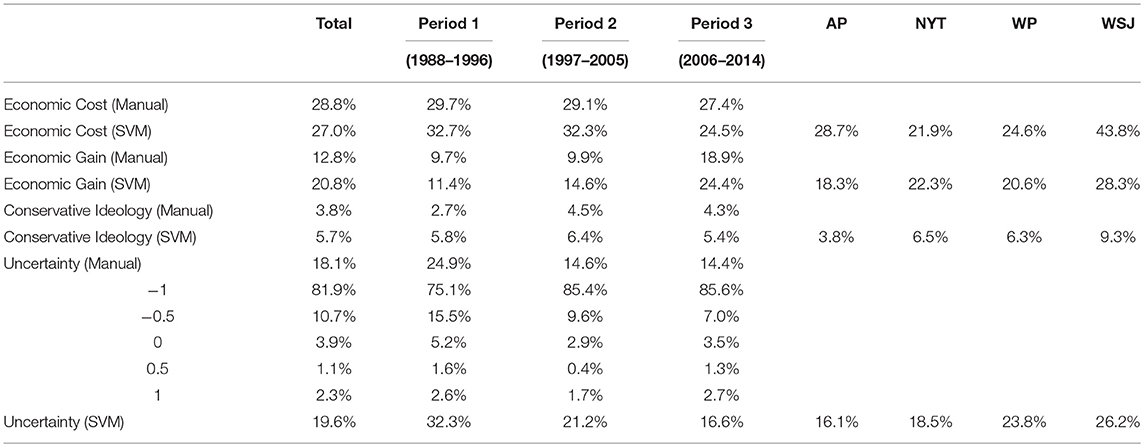

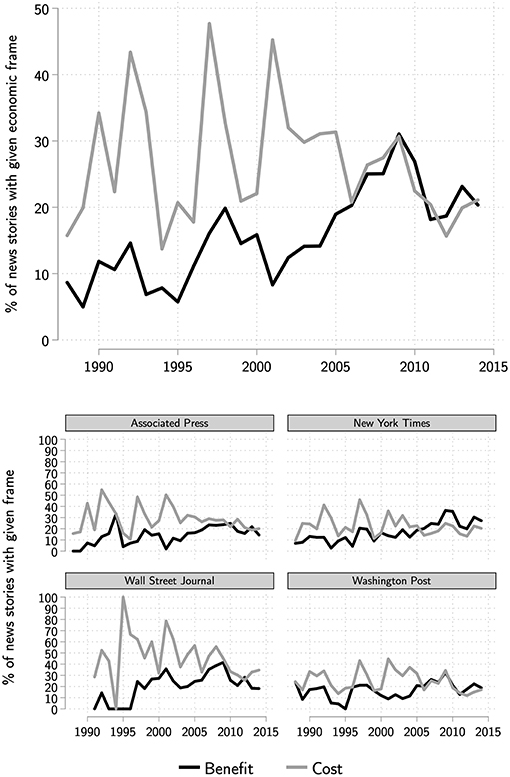

We begin by presenting the results for economic frames. The results of our manual coding are displayed in Table 2. It reveals that, across all three periods, close to 30% of all stories had reference to possible economic costs of climate mitigation. This was largely consistent across all three time periods of our study. In contrast, frames focusing on economic benefits of climate policy are relatively limited, comprising just under 13% of coverage. However, there has been a notable spike in such coverage more recently in period 3 (18.9%). SVM classification yields largely similar results. Close to 30% of articles contain frames related to economic costs, and there has been a modest decrease in the most recent time period (24.4%), while 20% have economic benefit frames, which have risen substantial in the most recent period (23.9%) compared to the earliest period (10.8%).

Figure 1 below presents the SVM results annually since 1988. Economic cost frames unsurprisingly appear to coincide with important policy debates such as the Rio conference, the Kyoto protocol, and Kyoto's implementation. In all three of these periods Republicans and their allies in heavy industry were active in framing the climate debate in terms of the cost of mitigation to the American economy due to the exclusion of developing countries from mandatory emissions reduction targets. Since 2001, however, it does appear that the presence of these frames in coverage have decline somewhat. In contrast, economic gain frames marched steadily upwards in the 2000s, coinciding with the changing posture by much of corporate America toward climate change mitigation. There now appears to be an even contest between economic cost and economic benefit frames in news coverage, which was far from the case in the 1990s.

Figure 1. Proportion of climate change news coverage with economic framing from 1988 to 2014 in our combined corpus (top panel) and by source (bottom panels).

The media's treatment of economic frames is relatively consistent across each of the outlets used here as shown in Table 2, with one notable exception. The conservative Wall Street Journal is substantially more likely to present economic cost frames (43.4%) compared to the others (24.7%, average), though it is also modestly more likely to also focus on gains (27.4 vs. 20.1%, average). In the temporal dynamics, however, each of our outlets are fundamentally similar. All four outlets have seen a gradual convergence in the promotion of economic cost and benefit frames in their coverage, as shown in Figure 1. In the contest to frame climate change mitigation as either a cost or a benefit, there is now a fair fight.

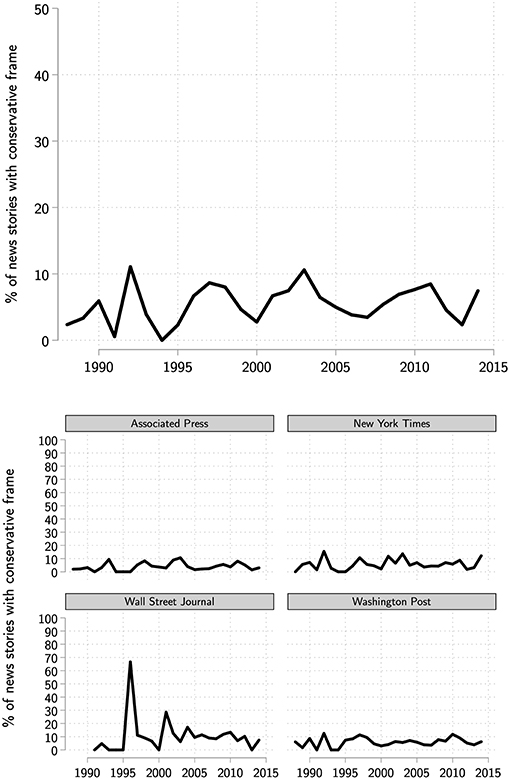

In sharp contrast, conservative ideological framing—independent of concerns for economic costs—is very limited. Our manual coding reveal that such frames are only present in under 4% of news coverage. This figure has remained relatively constant across the three periods of our study. Our SVM algorithm returned results broadly similar to our coding, though estimating the percentage slightly higher (5.6%). There were only a few times in the past few decades when the conservative framing was featured in more than 10% of the news articles. As shown in Figure 2, in the years of peak salience of the issue, 2007–2009, conservative framing was featured in 3, 5, and 7% of all news coverage, respectively. Interestingly, there is little evidence of a rise in conservative ideological framing, despite increasing partisan polarization on climate change.

Figure 2. Proportion of climate change news coverage with conservative framing from 1988 to 2014 in our combined corpus (top panel) and by source (bottom panels).

There are, however, important differences between the Wall Street Journal and the other papers. This is unsurprising, given that the Wall Street Journal is considered the flagship newspaper of the conservative movement. There are several years when the conservative framing was featured prominently in the climate coverage in the Journal. That was especially the case in 1996 and 2001, where the conservative frame was present in 67 and 29% of the climate stories in the Wall Street Journal. In the years when the issue was covered most prominently, however, even the Journal used the framing at the rates comparable to other news outlets, usually below 10% of all coverage. Conservative and Republican elites have not typically framed opposition to climate change in grand ideological terms, relying instead on arguments about economic cost, and, to a lesser degree, scientific uncertainty, as we shall see below.

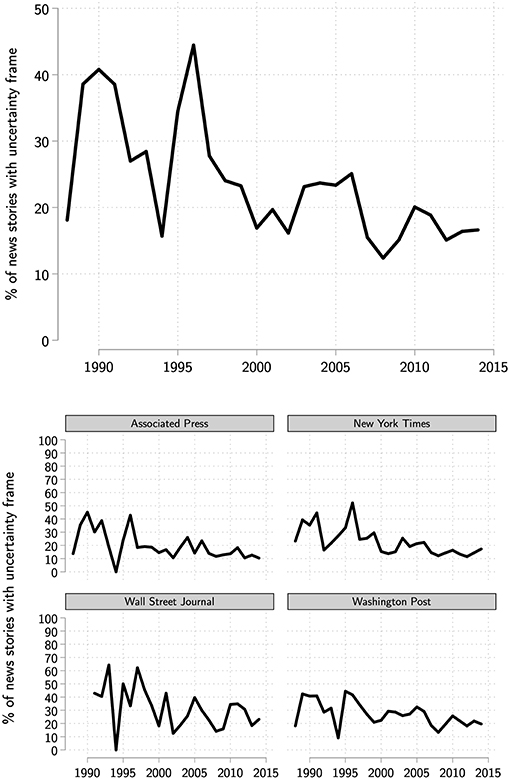

Our manual coding also reveals that uncertainty frames are not present in climate change coverage at levels we might expect. This is in line with past work that shows organized climate skeptics are rarely featured in the news (Merkley and Stecula, 2018). Only 18% of coverage features any discussion that contradicts the IPCC climate consensus. And, of this share of coverage, well over half (10.7%) is still slanted in a way that privileges voices aligned with the IPCC consensus. Much dreaded “false balance” in climate coverage is rare. It also appears that the news media has improved in their coverage on this score. The share of coverage with any uncertainty framing has decreased from 25% in period 1 to ~14% in period 3.

The SVM results are consistent with our manual coding. It found 19% of articles to have some presence of uncertainty framing, which has dropped from 32% in period 1 to 16% in period 3. This is reflected in the annual plot of our SVM results in Figure 3. Uncertainty framing spiked to over 40% in periods of intense policy debate in the 1990s, but has marched steadily downward since, such that the best estimate of uncertainty framing in coverage at present is around 10%.

Figure 3. Proportion of climate change news coverage with uncertainty framing from 1988 to 2014 in our combined corpus (top panel) and by source (bottom panels).

Again, results are reasonably consistent across our sources, though the conservative Wall Street Journal focuses on uncertainty frames modestly more than our other outlets on average (25.4 vs. 19.4% average). The dynamics shown in Figure 3 below, however, illustrate that the decline in uncertainty framing is consistent across all of our sources, such that the Wall Street Journal has largely converged with the rest. Again, it is worth noting that instances of “false balance” are likely even lower than these rather liberal estimates of uncertainty. The news media have simply not treated climate science in a balanced way, and they have increasingly purged any reference to uncertainty surrounding the IPCC consensus from their coverage.

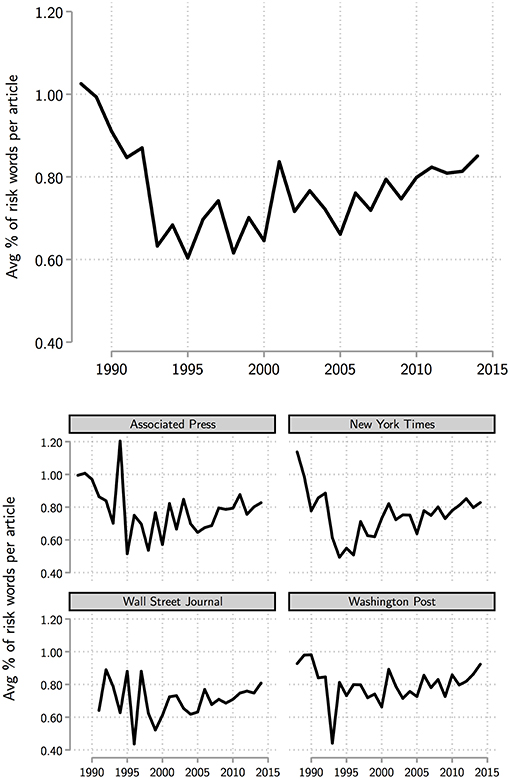

Risk framing is measured differently than economic cost and benefit frames and other results discussed above due to a different method employed in capturing it. The results are presented in Figure 4. The y-axis indicates the percentage of words in an average article each year that indicate risk. The numbers themselves are low, and somewhat difficult to substantively interpret, but what is clear is that language conveying danger and risk is increasingly present in climate change coverage as the issue has risen in salience. Between 1995 and 2014, risk language usage in the press increased by over 35%. There are no substantive differences between the outlets. All display similar patterns of increased usage of risk framing, as the issue has increased in salience in the mid-2000s. What might be surprising, however, is a relatively high usage of risk language in the early 1990s. The reason for that peak, however, is rooted in a relatively low number of articles in that time-frame, especially before the Kyoto Protocol. The bulk of the stories in that period primarily focused on the science of climate change, and therefore language relating to risk was comparatively common.

Figure 4. Frequency of risk related language in climate change news coverage from 1988 to 2014 in our combined corpus (top panel) and by source (bottom panels).

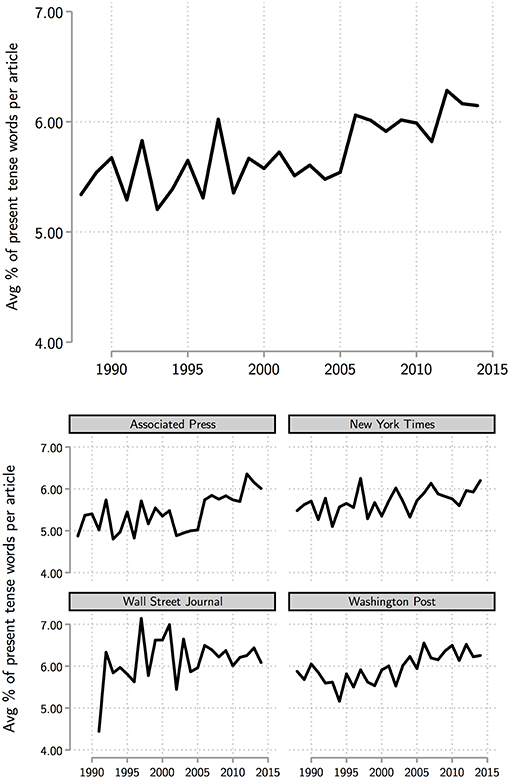

We also measured framing relating to temporal distance using the dictionary approach—specifically words used in climate coverage that were in the present tense. As Figure 5 demonstrates, there has been an increase in present-tense language around the time when the issue exploded in salience, in mid-2000s, around the release of Al Gore's award winning documentary An Inconvenient Truth. This pattern appears to be modestly stronger with coverage by the Associated Press and the Washington Post, though it is, on average, higher now than in the past for all four outlets.

Figure 5. Frequency of present-tense related language in climate change news coverage from 1988 to 2014 in our combined corpus (top panel) and by source (bottom panels).

Discussion

Frames play an essential role in distilling complex topics into more manageable components so that people can identify its relevance and form opinions (Spence and Pidgeon, 2010). It is inevitable in the context of climate change because of the sheer number of dimensions associated with the issue—questions pertaining to the science and future climate forecasts, impacts, public policy, and related tradeoffs, among others. Frames, however, are not neutral. Journalists, interest groups, environmentalists, and party elites all compete to elevate frames conducive to their interests and ideologies (Nisbet, 2009).

A rich literature has emerged using experimental methods to examine the influence of these frames on public attitudes toward climate science and mitigation policy. Together, these works have provided important insights into the public's complex relationship with climate change. We know that frames emphasizing economic cost reduce support for climate mitigation (Davis, 1995; Vries et al., 2016), but those emphasizing gains are important at marshaling support (Spence and Pidgeon, 2010). Scholars have speculated that uncertainty frames confuse the public about the state of the science, and reduce their propensity to engage in mitigation behavior (Boykoff and Boykoff, 2007), and there is some experimental evidence in support of that notion (Dixon and Clarke, 2013; Clarke et al., 2015; Dixon et al., 2015; Koehler, 2016). We also know that less polarizing climate change discourse may reduce Republican antipathy toward climate action (Tesler, 2018). However, we believe that more work needs to address the information environment in which citizens learn about climate change. How often are these frames present? Has the dominance of certain frames changed over time? Are there differences across outlets? Scholars need to increase their focus on the study of content, particularly in the news sources that most citizens learn about political issues.

We find here reason for optimism. Many of the frames which scholars have identified as reducing citizen propensity to support and engage in climate action have been on the decline in the mainstream media—even in the flagship publication of the conservative movement: the Wall Street Journal. Frames pertaining to the possible economic harms of climate mitigation policy have been prominent in the past, but appear to be on the decline. Similarly, frames related to uncertainty in the IPCC consensus have been in sharp decline, and true instances of “false balance” have never been particularly common. Conservative ideological frames, for their part, have never gotten traction in mainstream news coverage and this is even true in the Wall Street Journal. The reason for this appears to be that economic cost is the argument of choice for conservative and Republican elites when communicating opposition to climate change mitigation policy. The three pillars of argument typically used by countermovement organizations and the Republican Party to undermine climate action have been muffled in dominant news outlets.

At the same time, frames conducive to the support and engagement in climate action by the general public have been on the rise. Frames that emphasize the economic benefits of climate action have been on the sharp ascent since 2008 and now match those of economic cost. There is now a fair fight between rival interpretations of the economic implications of greenhouse gas emission reductions. The use of the present tense is also more common in climate coverage, as is the presentation of language related to risk. Climate discourse is increasingly focused on the risk posed by inaction and the here and now. To the extent that citizens may not be informed of the gravity of the risk posed by uncontrolled greenhouse gas emissions, or discount threats that appear to be far in the future, these are welcome developments.

We cannot definitely say why these changes are occurring with a study of news content. However, it seems likely that the sharp changes we have observed in the prevalence of economic frames is a result of the changing posture of the business community. A key characteristic of the Kyoto debate was the monolithic opposition of American business to climate mitigation. Notwithstanding the continued reticence of the fossil fuel industry—this is no longer true. Many sectors of American industry see opportunities for profit with climate mitigation strategies—or, at least publicly recognize the need to minimize future risks posed by climate change (Sullivan, 2008; Lee, 2012; Weinhofer and Busch, 2013; Doda et al., 2015). Other companies have emerged explicitly to capitalize on the emerging green economy. News content is reflecting these changes.

One limitation of our automated content analysis approach was the need to code distinct dimensions of economic frames together within the respective umbrellas of economic costs and benefits. In so doing, we may have lost important nuance. We cannot, for instance, say whether frames related to disemployment effects of mitigation policy are more common than those focusing on energy costs. We believe this tradeoff was necessary to maximize the precision of our over time estimates—a task which is much more suited for automated content analysis compared to the hand coding of a smaller batch of articles. Future work should make more thorough use of human coding to tease out the prevalence of different dimensions of economic costs and benefits and, if possible, how each of them may have changed over time.

Similarly, it is likely that news content is reflecting changes in climate science. The IPCC consensus is robust, but there is no doubt that confidence in its main tenants has solidified over time as data and research has accumulated. Journalists have likely reflected this change in their content. Our hand coding reveals that most of the decline in the use of uncertainty frame has been found in stories that reference uncertainty, but largely support the IPCC consensus (scored −0.5) and those that provide a balance of perspectives on the consensus (scored 0). These are primarily news stories. In contrast, there has been no notable decrease in articles that primarily reject the IPCC consensus, which are largely op-eds. In short, whatever problem that remains is primarily due to news outlets lending their op-ed pages to climate skeptics rather than the operation of a journalistic norm of balance—a point reinforced with the even lower share of coverage using uncertainty frames by the AP newswire. The implication is that continued scholarly focus on false balance and organized skeptics is perhaps misplaced—at least as far as understanding public opinion is concerned. Further research should explore the roots of these changes in journalist practice to allow us to avoid similar problems of false balance on other issues of scientific and expert consensus.

Not all is well, though. It is heartening that conservative ideological frames are rarely used to oppose climate action, but at the same time these themes are not used in support of it either. Research has found that conservative frames in support of climate action can be highly persuasive to conservative and Republican identifiers (Campbell and Kay, 2014; Dixon et al., 2017). We were not able to find enough instances of this frame's use to reliably train an algorithm to measure its (lack of) prevalence. Science communicators and journalists need to do more to elevate conservative arguments for climate action and those making these arguments.

Perhaps even more importantly, previous work has shown that there has been a steady rise in the presence of cues or messages from party elites on climate change (Merkley and Stecula, 2018). This may help explain why, for all the gains that have been made in raising the awareness among Americans to the threat of climate change, the public has also polarized on the topic. A wide array of research on public opinion formation has shown such cues to be informative for citizens and persuasive on a wide range of issues (Zaller, 1992; Cohen, 2003; Berinsky, 2009), because both partisanship and negative partisanship form critical parts of their social identity (Green et al., 2002; Iyengar et al., 2012). Mobilizing a societal consensus on climate action requires an awareness of this dynamic in the information environment and solutions that can overcome polarizing elite discourse.

We hope that our findings will not only contribute to the academic body of work on this topic, but will also prove useful for journalists, science communicators, and policy makers. For journalists to change and improve their practice, they first need to know what their current practice is and how its changed over time. One specific issue with climate coverage, for example, is the lack of conservative frames supporting climate action. Since science communicators believe these frames are the key to persuading Republicans, as was highlighted above, journalists should do a better job amplifying those voices in their coverage. Furthermore, as the issue of climate change has been extensively studied, journalists and media professionals can use some of the lessons of this coverage and apply them to other issues with broad scientific consensus, but were coverage is routinely worse, such as the safety of genetically modified foods.

Future scholarship needs to bridge experimental research examining the effects of frames and cue sources on climate attitudes with descriptive analyses of the real world information environment where Americans are exposed to these messages. Both are needed to allow science communicators to effectively craft strategies to mobilize Americans for climate action. We hope that our paper provides useful information to scholars seeking to design stronger, more externally-valid experimental studies and journalists concerned with writing news content conducive to raising public concern about the threat of climate change.

Furthermore, future work on this topic needs to more thoroughly link the body of work that has developed on this topic in a comparative context. As the news media environment is becoming more global, particularly with the rise of the importance of social media in the information environment of an average person, a systematic understanding of how climate change is covered and how that coverage changed in different countries with different media systems, might illuminate best practices for science communicators, policymakers, journalists, and members of the interested public in different institutional contexts.

Data Availability

Replication data is available at https://osf.io/gfyhe/.

Author Contributions

DS and EM collected the data and produced the tables and figures, wrote, and edited the article, as well as handled the revisions during the review process. EM performed the hand coding and ran machine learning analysis and wrote the bulk of the data and methods, results, and discussion. DS performed the dictionary content analysis and validated hand coding and wrote the bulk of the initial literature review and the introduction.

Funding

Both DS and EM received doctoral dissertation funding, which this project is a part of, from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant/Award Numbers: 752-2015-2536,767-2015-2504).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor, John Cook, and the reviewers for their thoughtful comments, and Kathleen Hall Jamieson for her support.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2013/aug/08/global-warming-denial-fox-news

2. ^https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2014/apr/08/fox-news-28-percent-accurate-climate-change

3. ^For example, Boykoff (2007) examined five U.S. and two U.K. newspapers in the years 2003–2005. Boykoff and Boykoff (2004) examined five American newspapers over a much longer period of 1988–2002, however, the issue of climate change didn't gain salience until post-2006 (see Merkley and Stecula, 2018). Boykoff and Boykoff (2007) expanded the scope of their work by focusing on a longer time period (1988–2004) and by adding broadcast television transcripts. Hoffman (2011), on the other hand, examined more recent coverage in major U.S. papers, but only over a very limited timespan: September 2007 to September 2009, and only in opinion editorials. Painter and Gavin (2016) examined climate coverage in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, among newspapers from other countries, but their temporal focus was limited to a period from November 19, 2009 to February 18, 2010.

4. ^Feldman et al. (2017) have analyzed climate change news coverage by examining different types of frames, including the economy, but their approach did not distinguish between economic cost and benefit, nor was it the central focus of their analysis.

5. ^http://www.journalism.org/fact-sheet/newspapers/

6. ^https://www.alexa.com/topsites/category/Top/News

7. ^https://www.ap.org/about/annual-report/2017/ap-by-the-numbers.html

8. ^http://www.journalism.org/2018/09/10/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2018/

9. ^https://www.nytimes.com/1988/06/24/us/global-warming-has-begun-expert-tells-senate.html

10. ^This was accomplished through a combination of human coding and supervised machine learning, where a sample of stories was hand coded as relevant or not and then the machine learning algorithm was used to apply that to our corpus.

11. ^The training and testing sets were pulled from a larger number of mainstream newspapers, which we have analyzed as part of our larger project studying climate change news content. However, only 30% of the training set came from other mainstream newspapers. For this paper, one researcher completed the hand coding, while the second randomly selected 10% of these hand coded items (200 articles) to assess the reliability of the coding. Our Krippendorff's Alpha score is 0.87 for economic cost frames (95% agreement), 0.92 for economic benefit frames (98% agreement), 0.88 for uncertainty frames (96% agreement), and 0.83 for conservative frames (99% agreement). The human coding input for the algorithm is thus highly reliable.

References

Antilla, L. (2005). Climate of scepticism: US newspaper coverage of the science of climate change. Global Environ. Change 15, 338–352. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.08.003

Bain, P. G., Milfont, T. L., Kashima, Y., Bilewicz, M., Doron, G., Garð*arsdóttir, R. B., et al. (2016). Co-benefits of addressing climate change can motivate action around the world. Nat. Climate Change 6, 154–157. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2814

Berinsky, A. J. (2009). In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq. University of Chicago Press.

Boykoff, M. T. (2007). Flogging a dead norm? Newspaper coverage of anthropogenic climate change in the United States and United Kingdom from 2003 to 2006. Area 39, 470–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2007.00769.x

Boykoff, M. T., and Boykoff, J. M. (2004). Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press. Global Environ. Change 14, 125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.001

Boykoff, M. T., and Boykoff, J. M. (2007). Climate change and journalistic norms: a case-study of US mass-media coverage. Geoforum 38, 1190–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.008

Brulle, R. J., Carmichael, J., and Jenkins, J. C. (2012). Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010. Climatic Change 114, 169–188. doi: 10.1007/s10584-012-0403-y

Campbell, T. H., and Kay, A. C. (2014). Solution aversion: on the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 107, 809–824. doi: 10.1037/a0037963

Carmichael, J. T., Brulle, R. J., and Huxster, J. K. (2017). The great divide: understanding the role of media and other drivers of the partisan divide in public concern over climate change in the USA, 2001–2014. Climatic Change 141, 599–612. doi: 10.1007/s10584-017-1908-1

Chong, D., and Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing Theory. Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 10, 103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

Clarke, C. E., Hart, P. S., Schuldt, J. P., Evensen, D. T. N., Boudet, H. S., Jacquet, J. B., et al. (2015). Public opinion on energy development: the interplay of issue framing, top-of-mind associations, and political ideology. Energy Pol. 81, 131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2015.02.019

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: the dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 85, 808–822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.808

Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S., and Ecker, U. K. H. (2017). Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PLoS ONE 12:e0175799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175799

Corbett, J. B., and Durfee, J. L. (2004). Testing public (Un)certainty of science: media representations of global warming. Sci. Commun. 26, 129–151. doi: 10.1177/1075547004270234

Curley, S. P., Yates, J. F., and Abrams, R. A. (1986). Psychological sources of ambiguity avoidance. Organ. Behav. Human Decision Process. 38, 230–256. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(86)90018-X

Dannenberg, A., Löschel, A., Paolacci, G., Reif, C., and Tavoni, A. (2015). On the provision of public goods with probabilistic and ambiguous thresholds. Environ. Resour. Econom. 61, 365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10640-014-9796-6

Davis, J. J. (1995). The effects of message framing on response to environmental communications. J. Mass Commun. Quart. 72, 285–299. doi: 10.1177/107769909507200203

Ditto, P. H., and Lopez, D. F. (1992). Motivated skepticism: use of differential decision criteria for preferred and nonpreferred conclusions. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 63, 568–584. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.568

Dixon, G., Hmielowski, J., and Ma, Y. (2017). Improving climate change acceptance among U.S. conservatives through value-based message targeting. Sci. Commun. 39, 520–534. doi: 10.1177/1075547017715473

Dixon, G. N., and Clarke, C. E. (2013). Heightening uncertainty around certain science: media coverage, false balance, and the autism-vaccine controversy. Sci. Commun. 35, 358–382. doi: 10.1177/1075547012458290

Dixon, G. N., McKeever, B. W., Holton, A. E., Clarke, C., and Eosco, G. (2015). The power of a picture: overcoming scientific misinformation by communicating weight-of-evidence information with visual exemplars. J. Commun. 65, 639–659. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12159

Doda, B., Gennaioli, C., Gouldson, A., Grover, D., and Sullivan, R. (2015). Are corporate carbon management practices reducing corporate carbon emissions? CSR Environ. Manage. 23, 257–270. doi: 10.1002/csr.1369

Druckman, J. N. (2001). The implications of framing effects for citizen competence. Pol. Behav. 23, 225–256. doi: 10.1023/A:1015006907312

Dunlap, R. E., and Jacques, P. J. (2013). Climate change denial books and conservative think tanks. Am. Behav. Sci. 57, 699–731. doi: 10.1177/0002764213477096

Dunlap, R. E., and McCright, A. M. (2011). Organized Climate Change Denial. The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566600.003.0010

Elliott, E., Seldon, B. J., and Regens, J. L. (1997). Political and economic determinants of individuals≫ support for environmental spending. J. Environ. Manage. 51, 15–27. doi: 10.1006/jema.1996.0129

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Farjam, M., Nikolaychuk, O., and Bravo, G. (2018). Does risk communication really decrease cooperation in climate change mitigation? Climatic Change 149, 147–158. doi: 10.1007/s10584-018-2228-9

Farrell, J. (2016a). Corporate funding and ideological polarization about climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016:201509433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509433112

Farrell, J. (2016b). Network structure and influence of the climate change counter-movement. Nat. Climate Change 6, 370–374. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2875

Feldman, L., Hart, P. S., and Milosevic, T. (2017). Polarizing news? Representations of threat and efficacy in leading US newspapers' coverage of climate change. Public Understand. Sci. 26, 481–497. doi: 10.1177/0963662515595348

Feygina, I., Jost, J. T., and Goldsmith, R. E. (2010). System justification, the denial of global warming, and the possibility of “system-sanctioned change.” Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 36, 326–338. doi: 10.1177/0146167209351435

Fischhoff, B., and Davis, A. L. (2014). Communicating scientific uncertainty. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111(Suppl. 4), 13664–13671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317504111

Flaxman, S., Goel, S., and Rao, J. M. (2016). Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. Public Opin. Quart. 80(S1), 298–320. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfw006

Friedman, S. M., Dunwoody, S., and Rogers, C. L. (Eds.). (1999). Communicating Uncertainty: Media Coverage of New and Controversial Science, 1st Edn. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

Giannoulis, C., Botetzagias, I., and Skanavis, C. (2010). Newspaper reporters' priorities and beliefs about environmental journalism: an application of Q-methodology. Sci. Commun. 32, 425–466. doi: 10.1177/1075547010364927

Golan, G. (2006). Inter-media agenda setting and global news coverage. J. Stud. 7, 323–333. doi: 10.1080/14616700500533643

Green, D., Palmquist, B., and Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan Hearts and Minds. Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.

Grimmer, J., and Stewart, B. M. (2013). Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Pol. Anal. 21, 267–297. doi: 10.1093/pan/mps028

Guess, A. (2016). Media Choice and Moderation: Evidence From Online Tracking Data. Available online at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/uk005hhio3dysm8/GuessJMP.pdf?dl=0

Hine, D. W., and Gifford, R. (1991). Fear appeals, individual differences, and environmental concern. J. Environ. Educ. 23, 36–41. doi: 10.1080/00958964.1991.9943068

Hoffman, A. J. (2011). Talking past each other? Cultural framing of skeptical and convinced logics in the climate change debate. Organ. Environ. 24, 3–33. doi: 10.1177/1086026611404336

Hornsey, M. J., and Fielding, K. S. (2016). A cautionary note about messages of hope: Focusing on progress in reducing carbon emissions weakens mitigation motivation. Global Environ. Change 39, 26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.04.003

IPCC (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report (Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Geneva, Switzerland. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., and Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Quart. 76, 405–431. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs038

Jacques, P. J., Dunlap, R. E., and Freeman, M. (2008). The organisation of denial: conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism. Environ. Pol. 17, 349–385. doi: 10.1080/09644010802055576

Jolley, D., and Douglas, K. M. (2017). Prevention is better than cure: addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 47, 459–469. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12453

Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment Decision Making 8, 407–424.

Kahan, D. M., Jenkins-Smith, H., and Braman, D. (2011). Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J. Risk Res. 14, 147–174. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2010.511246

Kahn, M. E., and Kotchen, M. J. (2010). Environmental Concern and the Business Cycle: The Chilling Effect of Recession (Working Paper No. 16241). National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.3386/w16241

Kappes, A., Nussberger, A.-M., Faber, N. S., Kahane, G., Savulescu, J., and Crockett, M. J. (2018). Uncertainty about the impact of social decisions increases prosocial behaviour. Nat. Human Behav. 2, 573–580. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0372-x

Koehler, D. J. (2016). Can journalistic “false balance” distort public perception of consensus in expert opinion? J. Exp. Psychol. 22, 24–38. doi: 10.1037/xap0000073

Krosnick, J. A., Holbrook, A. L., and Visser, P. S. (2000). The impact of the fall 1997 debate about global warming on American public opinion. Public Understand. Sci. 9, 239–260. doi: 10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/303

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 108, 480–498. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Lacy, S., Watson, B. R., Riffe, D., and Lovejoy, J. (2015). Issues and best practices in content analysis. J. Mass Commun. Quart. 92, 791–811. doi: 10.1177/1077699015607338

Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environ. Commun. 4, 70–81. doi: 10.1080/17524030903529749

Lee, S. (2012), Corporate carbon strategies in responding to climate change. Business Strategy Environ. 21, 33–48. doi: 10.1002/bse.711.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., and Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 13, 106–131. doi: 10.1177/1529100612451018

McCright, A. M., Charters, M., Dentzman, K., and Dietz, T. (2016). Examining the effectiveness of climate change frames in the face of a climate change denial counter-frame. Topics Cogn. Sci. 8, 76–97. doi: 10.1111/tops.12171

McDonald, R. I., Chai, H. Y., and Newell, B. R. (2015). Personal experience and the ‘psychological distance’ of climate change: an integrative review. J. Environ. Psychol. 44, 109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.10.003

McGaurr, L., Lester, L., and Painter, J. (2013). Risk, uncertainty and opportunity in climate change coverage: Australia compared. Austr. J. Rev. 35:21.

McMichael, A. J., Woodruff, R. E., and Hales, S. (2006). Climate change and human health: present and future risks. Lancet 367, 859–869. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68079-3

Merkley, E., and Stecula, D. A. (2018). Party elites or manufactured doubt? The informational context of climate change polarization. Sci. Commun. 40, 258–274. doi: 10.1177/1075547018760334

Milinski, M., Sommerfeld, R. D., Krambeck, H.-J., Reed, F. A., and Marotzke, J. (2008). The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 2291–2294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709546105

Morton, T. A., Rabinovich, A., Marshall, D., and Bretschneider, P. (2011). The future that may (or may not) come: how framing changes responses to uncertainty in climate change communications. Global Environ. Change 21, 103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.09.013

Nicolaij, S., and Hendrickx, L. C. W. P. (2003). “The influence of temporal distance of negative consequences on the evaluation of environmental risks,” in Human Decision Making and Environmental Perception. Understanding and Assisting Human Decision Making in Real-Life Situations. eds L. C. W. P. Hendrickx, W. Jager, and L. Steg (Groningen: University of Groningen) Available online at: https://www.rug.nl/research/portal/publications/the-influence-of-temporal-distance-of-negative-consequences-on-the-evaluation-of-environmental-risks(92abf041-104a-4289-b813-64fecb2a065b).html

Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environ. Sci. Pol. Sustain. Dev. 51, 12–23. doi: 10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23

Nyhan, B., and Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: the persistence of political misperceptions. Pol. Behav. 32, 303–330. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Oreskes, N. (2004). The scientific consensus on climate change. Science 306, 1686–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1103618

Oreskes, N., and Conway, E. M. (2011). Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues From Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (Reprint edition). New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

Painter, J., and Ashe, T. (2012). Cross-national comparison of the presence of climate scepticism in the print media in six countries, 2007–10. Environ. Res. Lett. 7:044005. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/044005