Abstract

Four experiments with rat subjects examined the role of context during the extinction of instrumental (free-operant) behavior. In all experiments, leverpressing was first reinforced on a variable-interval 30-s schedule and then extinguished before being tested in the extinction and renewal contexts. The results identified three important variables affecting the renewal effect after instrumental extinction. First, ABA and ABC forms of renewal were strengthened by increasing the amount of acquisition training. This suggests that the strength of the association learned during acquisition, or the final level of performance, influences the degree of renewal after extinction. The effect of the amount of training was modulated by the second factor, the degrees of generalization from the acquisition and extinction contexts to the test context. The third variable was acquisition training in multiple contexts, which was shown to strengthen ABC renewal. Methodological, theoretical, and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Instrumental behavior is acquired when the performance of a response, such as a leverpress, results in the delivery of a biologically significant outcome, such as a food pellet. In such a procedure, the rate of leverpressing usually increases as training progresses. One way in which the behavior can be reduced is through a procedure known as extinction. Here, the outcome (the food pellet) is no longer presented when the response is made, and the rate of behavior (i.e., leverpressing) decreases. Extinction is an important phenomenon because it is a fundamental process of behavior change. Furthermore, instrumental learning processes have been suggested to play a role in drug addiction (e.g., Everitt & Robbins, 2005) and overeating (e.g., Bouton, 2011), and extinction is one procedure that can reduce unwanted instrumental behaviors.

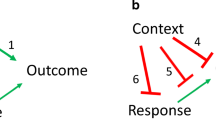

One important fact about extinction is that it does not result in the erasure of the original learning. Extensive research in Pavlovian conditioning (see Bouton, 2002, 2004) has indicated that instead extinction likely reflects new learning that is especially context dependent. This context dependence is demonstrated in the renewal effect. In renewal, following extinction in one context, responding returns (renews) when testing occurs outside the context of extinction. Although there is a growing parallel between Pavlovian extinction and instrumental extinction, the extent of the parallel regarding the renewal effect has not been clear. Several reports, with drugs or food as reinforcers, have demonstrated a renewal of extinguished instrumental responding when subjects are removed from the extinction context and returned to the original acquisition context (Bossert, Liu, Lu, & Shaham, 2004; Chaudri, Sahuque, & Janak, 2009; Crombag & Shaham, 2002; Hamlin, Clemens, & McNally, 2008; Hamlin, Newby, & McNally, 2007; Nakajima, Tanaka, Urushihara, & Imada, 2000; Zironi, Burattini, Aircardi, & Janak, 2006). However, there is less evidence that removal from the extinction context alone (without a return to the acquisition context) results in response recovery. For example, several authors have failed to detect AAB renewal, in which acquisition and extinction occur in Context A and testing occurs in Context B (see Bossert et al., 2004; Crombag & Shaham, 2002; Nakajima et al., 2000). If instrumental extinction is similar to Pavlovian extinction, removal from the extinction context should then be sufficient to cause renewal of responding.

A recent series of experiment by Bouton, Todd, Vurbic, and Winterbauer (2011) demonstrated three forms of renewal following instrumental extinction. In one experiment, renewal of instrumental responding occurred when extinction took place in Context B and testing occurred in Context A (ABA renewal). Responding also renewed when extinction occurred in Context A and testing occurred in Context B (AAB renewal). In a different experiment, renewal occurred when rats were trained, extinguished and tested in three separate contexts (ABC renewal). Overall, these experiments demonstrated a parallel between Pavlovian and instrumental extinction: Both seem to reflect new learning that is especially context dependent.

One question about the data reported by Bouton et al. (2011) was the size of the ABC renewal effect. Although statistically robust (e.g., 15 of 16 rats responded more in Context C than in Context B during testing), the increase in the rate of leverpressing from the context of extinction to the test context was not especially large numerically, and clearly was not as large as in ABA renewal. However, it is worth noting that the Bouton et al. (2011) experiments involved a very modest amount of acquisition training (only five or six 30-min sessions). The aim of the present experiments was thus to further compare ABA and ABC renewal and to examine variables that might influence their magnitudes.

The purpose of Experiment 1 was to ask whether ABC renewal could be strengthened by giving extended acquisition training prior to extinction. Experiment 2 compared the effects of the amount of acquisition on both ABC and ABA renewal. Experiment 3 tested the hypothesis that context similarity may influence instrumental renewal by encouraging retrieval of acquisition or extinction during testing. Finally, Experiment 4 tested the hypothesis that acquisition in multiple contexts increases ABC renewal. Overall, the results suggest that the amount of acquisition training, contextual similarity, and acquisition in multiple contexts strongly influence the strength of renewal after the extinction of instrumental learning.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 examined whether ABC renewal would be strengthened by a training procedure that increased the final level of acquisition performance. In our previous demonstration of ABC renewal (Bouton et al., 2011), the rat subjects received only 5 30-min sessions of acquisition. In the present experiment, one group of rats received 12 daily 30-min sessions of leverpress training in Context A, and another group received 4 daily sessions. Following 4 sessions of extinction in Context B, all rats were tested for renewal. The renewal test was performed within subjects: All rats were tested in both Contexts B and C in a counterbalanced order (Bouton & Ricker, 1994; Bouton et al., 2011; Rescorla, 2008). If the amount of training affects ABC renewal, then the group given more acquisition would be expected to press more in Context C than would the group given the relatively brief acquisition period.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 16 naive female Wistar rats purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constance, Quebec). They were between 75 and 90 days old at the start of the experiment and were individually housed in suspended wire mesh cages in a room maintained on a 16:8- h light:dark cycle. Experimentation took place during the light period of the cycle. The rats were food deprived to 80% of their initial body weights throughout the experiment.

Apparatus

For all rats, a single set of four operant chambers served as Context A. The chambers were slightly modified versions of Med Associates (St. Albans, VT) model ENV-007-VP chambers. They measured 30.5 × 24.1 × 29.2 cm (l × w × h) and were individually housed in sound attenuation chambers. Ventilation fans provided background noise of 65 dB, and the boxes were lit with two 7.5-W incandescent bulbs mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuation chamber. The front and back walls were brushed aluminum, while the side walls and ceiling were clear acrylic plastic. Recessed 5.1 × 5.1 cm food cups were centered in the front wall and positioned near floor level. A 4.8-cm-long stainless steel retractable operant lever protruded 1.9 cm from the front wall when extended and was positioned 6.2 cm above the grid floor to the right of the food cup. The floor was composed of stainless steel rods (0.48 cm in diameter) spaced 1.6 cm apart from center to center and mounted parallel to the front wall. The ceiling and left side wall had black horizontal stripes, 3.8 cm wide and 3.8 cm apart. A dish containing 5 ml of a 2% anise solution (McCormick & Co.) was placed outside of each chamber near the front wall.

Two other sets of four conditioning chambers housed in separate rooms of the laboratory served as Contexts B and C (counterbalanced). Each chamber was housed in its own sound attenuation chamber. All boxes of these two sets were of the same design (Med Associates, model ENV-008-VP), which was different from that of Context A (ENV-007-VP). They measured 30.5 × 24.1 × 21.0 cm (l × w × h). In one set of boxes (ENV-008-VP), the side walls and ceiling were made of clear acrylic plastic, while the front and rear walls were made of brushed aluminum. The floor was made of stainless steel grids (0.48 cm diameter) staggered such that odd- and even-numbered grids were mounted in two separate planes, one 0.5 cm above the other. A recessed 5.1 × 5.1 cm food cup was centered in the front wall approximately 2.5 cm above the level of the floor. Retractable levers were positioned to the left and right of the food cup. These levers were 4.8 cm long and were positioned 6.2 cm above the grid floor. The right lever protruded 1.9 cm when extended (the left lever remained retracted over the course of the experiment). A pair of 28-V panel lights (2.5 cm in diameter) were attached to the wall 10.8 cm above the floor and 6.4 cm to both the left and right of the food cup. These chambers were illuminated by two 7.5-W incandescent bulbs mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuation chamber, approximately 34.9 cm from the grid floor at the front wall of the chamber. Ventilation fans provided background noise of 65 dB. This set of boxes had no distinctive visual cues. A dish containing 5 ml of Rite Aid lemon cleaner (Rite Aid Corp., Harrisburg, PA) was placed outside of each chamber near the front wall.

The second set of boxes was similar to the lemon-scented boxes (e.g., also model ENV-008-VP, with similar placements of levers and panel lights), except for the following features. In the second set of boxes, one side wall had black diagonal stripes, 3.8 cm wide and 3.8 cm apart. The ceiling had similarly spaced stripes oriented in the same direction. The grids of the floor were mounted on the same plane and were spaced 1.6 cm apart (center to center). These chambers were illuminated by one 7.5-W incandescent bulb mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuation chamber, near the back wall of the chamber. A distinct odor was continuously presented by placing 5 ml of Pine-Sol (Clorox Co., Oakland, CA) in a dish outside the chamber.

The reinforcer was a 45-mg grain-based rodent food pellet (TestDiet, Richmond, IN). The apparatus was controlled by computer equipment located in an adjacent room.

Procedure

On Day 1, all rats were trained to retrieve food pellets from the magazine in each context in a single 32-min session. Approximately 60 pellets were delivered randomly on average every 30 s. Rats received a common context order of A then B then C. Following magazine training, rats were then trained in Context A to leverpress for food pellets on a variable-interval 30-s (VI-30) reinforcement schedule. Each acquisition session was 32 min long and began with a 2-min interval with no programmed experimental events. After 2 min, the lever was inserted into the chamber and the schedule was in effect. Then, 30 min later, the lever was retracted and the session ended. For the first 8 days, 8 rats received training in Context A, while the other 8 rats were simply handled. On Day 9, the handled rats joined the other rats and began training in Context A for the next 4 days. Thus, one group of 8 rats received 12 daily sessions of leverpress training in Context A (Group ABC-12), and one group of rats received 4 daily sessions of leverpress training (Group ABC-4). Following acquisition, both groups received four sessions of extinction in Context B. The extinction procedure was identical to the procedure for acquisition, except that leverpresses did not result in pellet delivery. Finally, the day following extinction, each rat was tested in both Contexts B and C in a counterbalanced order. Test sessions began with a 2-min interval, after which the lever was inserted. Leverpresses were recorded for the next 10 min, at which point the lever was retracted and the test session was complete. Test sessions were separated by approximately 1 h. No pellets were delivered during testing.

To summarize, all rats received acquisition training in the anise-scented boxes (Context A), and then half received extinction in the lemon-scented boxes and half received extinction in the Pine-Sol-scented boxes. Each rat was then given renewal testing following the usual procedure in both the lemon-scented and Pine-Sol-scented boxes.

The results were evaluated with analyses of variance (ANOVAs) using a rejection criterion of p < .05.

Results

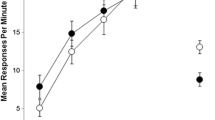

The results of the acquisition and extinction sessions are shown in Fig. 1. Separate within-subjects ANOVAs on each group’s responding over the acquisition sessions revealed a significant effect of session for Group ABC-12, F(11, 77) = 25.90, and Group ABC-4, F(3, 21) = 18.65, indicating that leverpressing increased over the course of acquisition for both groups. Groups were compared on their first four sessions of acquisition to determine whether initial acquisition of leverpressing occurred at similar rates. This analysis revealed a significant effect of session, F(3, 42) = 42.10, but neither the group effect nor the group × session interaction was significant, Fs < 1. The last four sessions of acquisition in Group ABC-12 were compared to the first four sessions of acquisition in Group ABC-4 in order to assess terminal response rates in both groups. A group × session ANOVA revealed a significant effect of session, F(3, 42) = 13.52, group, F(1, 14) = 11.88, and a group × session interaction, F(3, 42) = 6.77. The effect of session was significant in Group ABC-4 (as reported above), but not in Group ABC-12, F(3, 21) < 1, suggesting that Group ABC-12 had reached asymptotic responding by this time. On the last day of acquisition, there was a significant effect of group, F(1, 14) = 5.36. Thus, at the end of acquisition Group ABC-12 leverpressed at a significantly higher rate than did Group ABC-4.

Mean responding during 30-min sessions of acquisition and extinction in Experiment 1. ABC-12, 12 sessions of acquisition; ABC-4, 4 session of acquisition

Both groups decreased their rates of leverpressing during extinction, but at different rates. A 2 (group: ABC-12 vs. ABC-4) × 4 (extinction session) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session, F(3, 42) = 97.15, and a significant group effect, F(1, 14) = 12.62, as well as a significant group × session interaction, F(3, 42) = 4.68. On the first day of extinction, Group ABC-12 responded more than Group ABC-4, F(1, 14) = 7.65, and this effect remained significant on the last day of extinction, F(1, 14) = 7.91. Thus, Group ABC-12 continued to leverpress more than Group ABC-4 throughout the course of extinction.

Renewal testing in Contexts B and C, which is shown in Fig. 2, was analyzed with a 2 (group: ABC-12 vs. ABC-4) × 2 (context: extinction vs. renewal) ANOVA. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of context, F(1, 14) = 8.66, indicating ABC renewal. However, no other main effect or interaction was significant, Fs < 1. There was thus no difference in the strength of renewal when acquisition had been conducted for 4 or 12 sessions.

Results of the renewal test from Experiment 1: Mean responding during the 10-min test session in the extinction context (Context B) and the renewal context (Context C). ABC-12, 12 sessions of acquisition; ABC-4, 4 session of acquisition

Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 replicated the results first reported by Bouton et al. (2011). After acquisition in Context A and extinction in Context B, responding renewed when testing occurred in Context C. This result is consistent with the view that extinction is relatively context specific (in contrast to initial learning), and that removal from the context of extinction is sufficient for relapse to occur. Overall, 13 of 16 rats responded more in Context C than in Context B.

In the present experiment, the amount of acquisition training had surprisingly little effect on ABC renewal, despite the fact that it promoted more responding during the training acquisition and extinction phases of the experiment. This suggests that under the present conditions, the strength of renewal does not depend substantially on the amount of training or the strength of responding. It is possible that any added benefit of extended training on the strength of instrumental responding may have been eliminated during the extinction phase of the experiment. However, Group ABC-12 continued to leverpress significantly more than Group ABC-4 throughout extinction (although this difference was no longer evident in Context B at test).

Another possibility is that the similarity between contexts could play a crucial role in determining performance at test. Such an analysis would suggest that extending the amount of acquisition could have an effect if Contexts A and C were made more similar. Experiment 2 therefore examined the effect of extended training on ABA renewal, where the similarity between the acquisition and renewal test contexts was maximal (i.e., identical). It also examined ABC renewal again with a procedure in which Contexts A and C were relatively similar (they were chambers modified from the same manufactured model). In Experiment 1, the extinction and test contexts, rather than the acquisition and test contexts, had been similar in this way.

Experiment 2

The purpose of Experiment 2 was to compare the impact of extended acquisition training on ABC and ABA renewal. As noted above, ABA renewal might be particularly sensitive to the effect of extended training because this form of renewal involves a return to the same context associated with the response during acquisition. If there is a benefit of extended acquisition on renewal, it should be revealed as increased responding when the animals are tested back in Context A. Failure to detect a benefit in ABA renewal would suggest little role for the relative similarity of contexts in producing the effect.

If ABA renewal is strengthened by extended training, control by similar contexts should be strengthened as well. It is notable that in Experiment 1, Contexts B and C were more similar to one another than they were to Context A, because they were modifications of the same manufactured box (ENV-008-VP). In Experiment 2, we therefore rearranged these boxes to play the role of Contexts A and C. If our assumptions about the similarity between our contexts are correct, then extended training might now create stronger renewal in the ABC design.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 32 naive female Wistar rats purchased from the same vendor as those in the previous experiment and maintained under the same conditions.

Apparatus

For all rats, a new set of four operant chambers housed in a third room in the laboratory served as Context B. The chambers were slightly modified version of Med Associates (St. Albans, VT) model ENV-008-VP. They measured 30.5 × 24.1 × 21.0 cm (l × w × h) and were individually housed in sound attenuation chambers. Ventilation fans provided background noise of 65 dB, and the boxes were lit with two 7.5-W incandescent bulbs mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuation chamber. The front and back walls were brushed aluminum, while the side walls and ceiling were clear acrylic plastic. Recessed 5.1 × 5.1 cm food cups were centered in the front wall and positioned near floor level. A 4.8-cm-long stainless steel retractable operant lever protruded 1.9 cm from the front wall when extended and was positioned 6.2 cm above the grid floor to the right of the food cup. The floor was composed of stainless steel rods (0.48 cm in diameter) spaced 1.6 cm apart from center to center and mounted parallel to the front wall. A dish containing 5 ml of white vinegar was placed outside of each chamber near the front wall.

The lemon-scented and Pine-Sol-scented operant chambers used in Experiment 1 served as Contexts A and C (counterbalanced). The lemon-scented boxes were now illuminated by only one 7.5-W incandescent bulb located near the front wall.

Procedure

On Day 1, each rat received three 15-min sessions of magazine training in which approximately 30 pellets were delivered randomly on average every 30 s. One session of magazine training occurred in each of Contexts A, B, and C, in that order. During magazine training, the response lever was retracted.

Following magazine training, rats were trained in Context A to leverpress for food pellets on a VI-30 reinforcement schedule. Each rat received two sessions of leverpress training per day, with an intersession interval of approximately 2 h. Otherwise, acquisition, extinction, and testing followed the procedures used in Experiment 1. For the first 8 sessions, 16 rats received training in Context A, while the other 16 rats were simply handled. On the next day, the remaining 16 rats began training in Context A for the next 2 days. Thus, one subset of 16 rats received 12 total sessions of leverpress training in Context A, and one subset of rats received 4 total sessions of leverpress training in Context A. Following acquisition, all animals received 4 sessions of extinction training in Context B, again with 2 sessions per day. During extinction, the lever was active, but no pellets were delivered. Following the extinction phase, there was a single day of testing, in which each rat was tested in both the extinction context and the renewal context. Half of the animals that had received 12 sessions of acquisition were tested in their original acquisition context (Group ABA-12), and the other half were tested in a third context (Group ABC-12). Similarly, for the rats that had received 4 sessions of acquisition, one group was tested in the acquisition context (ABA-4), and another was tested in a third context (ABC-4). Thus, the design was a 2 × 2 factorial, with renewal type (ABA vs. ABC) and amount of acquisition (12 vs. 4 sessions) as factors. At the renewal test, half of the animals in each group were tested in the extinction context first, and the other half were tested in their respective renewal context first. No pellets were delivered during testing.

In the present experiment, all rats received extinction training in the vinegar-scented boxes (Context B). The lemon- and Pine-Sol-scented rooms were counterbalanced as the acquisition and renewal contexts.

Results

The results of the acquisition and extinction phases are presented in Fig. 3. Leverpress training proceeded as expected. A 2 (group: ABA-12 vs. ABC-12) × 12 (session) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F(11, 154) = 39.51, indicating that groups receiving 12 sessions of acquisition increased their rates of leverpressing over training. Groups that received 4 sessions of acquisition also increased their rates of leverpressing over training, F(3, 42) = 67.20. The first 4 sessions of Groups ABA-12 and ABC-12 were compared to the first four sessions of Groups ABA-4 and ABC-4. A 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 2 (amount of acquisition: 12 vs. 4 sessions) × 4 (session) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session, F(3, 84) = 130.99, and a significant amount of acquisition × session interaction, F(3, 84) = 3.76. No other main effects or interactions were significant, Fs < 1. Responding appeared to increase more rapidly in the rats that received the start of acquisition later. The last 4 sessions of acquisition for the groups that received 12 sessions were compared to the 4 sessions of acquisition for the other two groups. A 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 2 (amount of acquisition: 12 vs. 4 sessions) × 4 (session) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session, F(3, 84) = 55.73, a significant main effect of amount of acquisition, F(1, 28) = 34.77, and a significant amount of acquisition × session interaction, F(3, 84) = 10.14. No other main effects or interactions were significant, Fs < 1. The interaction suggests that the groups trained for 12 sessions were changing at a slower rate than the groups trained for 4 sessions. Finally, a 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 2 (amount of acquisition: 12 vs. 4 sessions) ANOVA on the last day of acquisition revealed a significant main effect of amount of acquisition, F(1, 28) = 7.85, indicating that groups trained for 12 sessions responded more than groups trained for 4 sessions. On the last day of acquisition, no other main effects or interactions were significant, Fs < 1. It is not surprising that there was no effect of the renewal type factor, considering that animals were not as of yet differentially treated based on this factor.

Mean responding during 30-min sessions of acquisition and extinction in Experiment 2. ABA-12 and ABC-12, 12 sessions of acquisition; ABA-4 and ABC-4, 4 sessions of acquisition

Leverpressing decreased over the course of extinction training for all groups, though not at the same rates. A 2 (amount of acquisition: 12 vs. 4 sessions) × 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 4 (session) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F(3, 84) = 55.71, and a main effect of amount of acquisition, F(1, 28) = 6.90. The main effect of amount of acquisition indicates that groups receiving 12 days of acquisition responded at a higher rate over the course of extinction. Although the session × amount of acquisition interaction was marginally significant, F(3, 84) = 2.40, p = .073, on the last day of extinction, no main effects or interactions were significant, largest F(1, 28) = 2.35, suggesting that groups were not different heading into the test sessions.

The results of the renewal test are depicted in Fig. 4. A substantial renewal effect was observed in both the extended-trained groups. A 2 (amount of acquisition: 12 vs. 4 sessions) × 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 2 (context: extinction vs. renewal) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of context, F(1, 28) = 198.89, indicating strong renewal. There were also significant main effects of amount of acquisition, F(1, 28) = 17.84, and renewal type, F(1, 28) = 4.38. Importantly, the amount-of-acquisition factor interacted with the context factor, F(1, 28) = 19.18, indicating that groups that had received extended training showed greater renewal. Separate ANOVAs revealed that the rats given more acquisition training responded more in the renewal context, F(1, 30) = 17.17, but not in the extinction context, F < 1. The renewal type factor did not interact with the context factor, F(1, 28) = 3.60, p = .068. Separate ANOVAs failed to find a significant effect of renewal type in either context, largest F(1, 30) = 2.55. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F(1, 28) = 2.10. Overall, these results suggest that extended acquisition training increased the size of renewal and that the increases were comparable for both Groups ABA and ABC.

Results of the renewal test from Experiment 2: Mean responding during the 10-min test session in the extinction context (Context B) and the renewal context (either Context A or C). ABA-12 and ABC-12, 12 sessions of acquisition; ABA-4 and ABC-4, 4 sessions of acquisition

Discussion

Experiment 2 replicated both ABA and ABC forms of instrumental renewal (Bouton et al., 2011). It also showed that extended acquisition training can, under the present circumstances, increase the strength of both ABA and ABC renewal. Groups that had received 12 sessions of acquisition training responded significantly more in the renewal context than did groups that had received 4 sessions of acquisition training. Furthermore, there was no evidence that extended acquisition training differentially affected one form of renewal; the amount of acquisition did not interact with renewal type. Thus, it is safe to conclude that additional acquisition training had comparable effects on both ABA and ABC renewal.

It is important to note that the effect of extended acquisition training on ABC renewal in Experiment 2 was different than in the results of Experiment 1. This was presumably due to the fact that the similar chambers used as Contexts B and C in Experiment 1 were used as Contexts A and C in the present experiment. Thus, the procedure in Experiment 2 would have promoted generalization between acquisition (A) and test (C), and this prediction was justified by the results we obtained. Overall, the present result suggests that the relative size of renewal, and its sensitivity to the amount of acquisition training, can be altered by treatments that promote generalization between extinction (B) and test (C) versus generalization between acquisition (A) and test (C).

One possible explanation for the effect of extended acquisition training is particularly straightforward. During acquisition training, the rate of responding was clearly increased due to extended acquisition training. Because extinction is thought to reflect new inhibitory learning, as opposed to the erasure of original learning, any differences observed in acquisition should also be present during renewal testing. This may be particularly true in ABA renewal, because this form of renewal involves a return to the context in which acquisition occurred. Importantly, the different results of Experiments 1 and 2 suggest that the same may be true of ABC renewal if Contexts A and C are not too dissimilar.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 was designed to test the role of contextual similarity on ABA and ABC renewal more directly by manipulating the context similarity factor within the same experiment. Two groups received acquisition in Context A, extinction in Context B, and testing in Context C. For one of these groups (Group ABC), acquisition occurred in a context (A) that was assumed to be relatively different from the pair of similar chambers that had played the role of Contexts B and C in Experiment 1. Thus, for Group ABC, extinction and testing occurred in similar contexts. For the other group (Group ABC Ext-D), extinction, rather than acquisition, occurred in the distinctive context, making Contexts A and C relatively similar (as in Experiment 2). (The group labels in this experiment note whether or not extinction occurred in the distinct [D] context.) Because Group ABC Ext-D received extinction (rather than acquisition) in the distinctive context, acquisition should generalize more from A to C, and the renewal effect should be comparatively strong.

Two ABA renewal groups were also studied. For one group (Group ABA), extinction and testing took place in the similar contexts also used for extinction and testing in Group ABC. In Group ABA, extinction (B) was therefore expected to generalize to test (A) and to weaken the renewal effect. The second ABA group (Group ABA Ext-D) received extinction in the distinctive context, just as for Group ABC Ext-D. For these animals, extinction was expected to generalize less to the test context, and the ABA renewal effect should thus be relatively robust.

It is important to emphasize that, based on our assumptions about the similarity between the experimental boxes, the present experiment directly assessed the basis of the differential results of Experiments 1 and 2. When extinction occurred in a distinctive context, the contexts used for acquisition and testing were the same contexts used in those phases of Experiment 2. When extinction did not occur in the distinctive context, these same contexts were instead the extinction and test contexts (as in Exp. 1). Experiment 3 thus tested the differential pattern of generalization inferred across Experiments 1 and 2 within the same experiment.

The experiment employed a 2 × 2 factorial design. One factor was renewal type, ABA versus ABC, and the other factor was the distinctiveness of the extinction context relative to the test context, distinctive or similar. Apart from experimentally examining the role of context generalization on the renewal effect, the experiment also allowed for a direct comparison of ABA and ABC renewal.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 32 female Wistar rats purchased from the same vendor as those in the previous experiments and maintained under the same conditions. The rats had previously participated in a Pavlovian conditioning experiment with tone and light-off CSs that took place in two different sets of conditioning chambers (not used in the present experiment).

Apparatus

The lemon, pine, and vinegar scented conditioning chambers were used for the present experiment. Context assignments are described below.

Procedure

On Day 1, each rat received three 15-min sessions of magazine training in which approximately 30 pellets were delivered randomly on average every 30 s. One session of magazine training occurred in each of Contexts A, B, and C, in that order. During magazine training, the lever was retracted.

The experimental procedures for acquisition, extinction, and test were the same as in Experiment 2. Following magazine training, rats were trained in Context A to leverpress for food pellets on a VI-30 reinforcement schedule. Acquisition lasted for 2 days (4 total sessions). This was followed by 2 days of extinction (4 total sessions) and a single test day. The context assignments were as follows. For one group of rats (Group ABC, n = 8), acquisition occurred in the vinegar chambers. For the other three groups, acquisition occurred in the pine and lemon chambers, counterbalanced. Groups ABC and ABA received extinction in the lemon and pine boxes (counterbalanced). Thus, Group ABA received acquisition, extinction, and testing in the lemon and pine boxes (counterbalanced as Contexts A and B). Group ABC received acquisition in the vinegar boxes and extinction and testing in lemon/pine (counterbalanced as B and C). For Groups ABC Ext-D and ABA Ext-D, extinction occurred in the vinegar boxes, and the lemon and pine boxes served as A and C. As noted above, the experimental design was a 2 × 2 factorial. One factor was renewal type (ABA vs. ABC), and the other factor was based on the relation between the extinction and test contexts (distinctive vs. similar).

Results

The results of the acquisition and extinction phases of the experiment are presented in Fig. 5. Leverpressing increased over the course of acquisition, and this did not depend on group membership. A 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 2 (extinction context: distinctive vs. similar) × 4 (session) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F(3, 84) = 137.76. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F(1, 28) = 1.97. A 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 2 (extinction context: distinctive vs. similar) ANOVA on the last session of acquisition revealed no significant differences, largest F(1, 28) = 1.3.

Mean responding during 30-min sessions of acquisition and extinction in Experiment 3. ABA Ext-D and ABC Ext-D, extinction in the distinct context

As expected, leverpressing decreased over the course of extinction. A 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 2 (extinction context: distinctive vs. similar) × 4 (session) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F(3, 84) = 122.49, and a main effect of extinction context, F(1, 28) = 5.97, as well as a significant session × extinction context interaction, F(3, 84) = 8.311. To further understand the source of the session × extinction context interaction, separate ANOVAs analyzed the first and last days of extinction. On the first day of extinction, there was a significant main effect of extinction context, F(1, 30) = 8.87. By the last session of extinction, the effect of extinction context was no longer significant, F < 1.Thus, groups in the distinctive context extinguished more rapidly than the other groups, but they did so to the same extent.

The test results are summarized in Fig. 6. Overall, renewal was evident in all groups, but it was generally stronger in the ABA format than in the ABC format, as well as stronger when extinction had been conducted in the distinct context. The test data were analyzed with a 2 (renewal type: ABA vs. ABC) × 2 (extinction context: distinctive vs. similar) × 2 (test context: extinction vs. renewal) ANOVA. The analysis revealed significant main effects of test context, F(1, 28) = 108.11, renewal type, F(1, 28) = 14.12, and extinction context, F(1, 28) = 9.04. The renewal type factor interacted with the test context factor, F(1, 28) = 15.34, suggesting that ABA renewal was larger than ABC renewal. Separate ANOVAs revealed that the effect of renewal type was significant in the renewal context, F(1, 30) = 11.28, but not in the extinction context, F < 1. The extinction context factor also interacted with the context factor, F(1, 28) = 15.02, suggesting that extinction in a distinctive context increased the strength of the renewal effect. Separate ANOVAs revealed that the effect of the distinctive extinction context was significant when tested in the renewal context, F(1, 30) = 8.36, but not when tested in the extinction context, F(1, 30) = 3.83. Finally, paired t tests revealed that the effect of test context was significant in all groups, minimum t(7) = 3.36. No other main effects or interactions were significant, Fs < 1.

Results of the renewal test from Experiment 3: Mean responding during the 10-min test session in the extinction context (Context B) and the renewal context (either Context A or C). ABA Ext-D and ABC Ext-D, extinction in the distinct context

Discussion

There were two main findings in Experiment 3. First, given the present configuration of the experimental chambers, ABA renewal was stronger than ABC renewal. Although the difference had only been marginal in Experiment 2, the present experiment demonstrated that a return to the acquisition context (ABA renewal) can produce more responding than does simple removal from the extinction context (ABC renewal). It is interesting to note, however, that ABA and ABC renewal can sometimes be very similar in strength. In the present experiment, Groups ABA and ABC Ext-D displayed nearly identical levels of responding at test.

The main finding from this experiment confirmed what was suggested from the comparison of the results of Experiments 1 and 2. Both ABA and ABC forms of renewal were stronger when extinction occurred in a context that was very different from the testing context. Thus, the distinctiveness and/or similarity of the extinction and test contexts (as well as of the conditioning and test contexts) plays a crucial role in the degree to which responding returns in both ABA and ABC renewal.

Experiment 4

Experiments 1–3 suggest that contextual similarity can play an important role in the renewal of extinguished instrumental (free-operant) behavior. Stronger renewal, and renewal that was sensitive to the amount of acquisition training, occurred when the acquisition and test contexts were relatively similar. Experiment 4 examined a different, though not unrelated, factor that might also increase ABC renewal. Rats received instrumental conditioning in either one context or two contexts. Instrumental conditioning in multiple contexts should presumably result in more contextual elements entering into the associative structure that is learned during acquisition (see, e.g., Atkinson & Estes, 1963). At test, this should promote the possibility of generalization of acquisition to a new context, because it increases the likelihood that elements in the new context will have been associated with acquisition.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 32 naive female Wistar rats purchased from the same vendor as those in the previous experiments and maintained under the same conditions.

Apparatus

For all rats, two sets of four operant chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) housed in separate rooms in the laboratory served as Contexts A and D (counterbalanced). One set was the anise-scented boxes used as Context A in Experiment 1. The other set had the same overall construction, dimensions, retractable levers, food cups, and sources of background noise and illumination as the anise-scented boxes (it was also a modification of Med Associates model ENV-007-VP). However, the floor consisted of alternating stainless steel rods with different diameters (0.48 and 1.27 cm), spaced 1.6 cm apart from center to center. The clear acrylic plastic ceiling and left side wall were covered with rows of dark dots (1.9 cm in diameter), each separated by approximately 1.2 cm. A dish containing 5 ml of 8% coconut solution (McCormick & Co.) was placed outside each chamber near the front wall.

The lemon-scented and Pine-Sol-scented operant chambers used in the previous experiments served as Contexts B and C (counterbalanced).

Procedure

On Day 1, magazine training was conducted in Contexts B and C, and then on Day 2 magazine training was conducted in Contexts A and D. Following magazine training, rats were trained to leverpress for food pellets on a VI-30 reinforcement schedule. Group A+ received six daily sessions of acquisition training in Context A, and Group A+D+ received three sessions of training in Context A and three sessions of training in Context D (single alternated). Two other groups received six daily training sessions in Context A. One of these groups was also exposed to Context D with no lever present to control for exposure to multiple contexts, and the other group was also exposed to Context A without the lever to control for extra sessions of contextual exposure with no lever present. On the 2nd, 4th, and 6th days, these rats were exposed to either Context A or Context D for a single, 32-min session in which the lever was retracted from the chamber. Thus, Group A+/D Exp received six sessions of leverpress training in Context A and was exposed to Context D three times. Group A+/A Exp received six sessions of leverpress training in Context A and was exposed to Context A three times. Following acquisition, all groups received four sessions of extinction in Context B. Finally, after extinction, each rat was tested in both Contexts B and C in a counterbalanced order.

Results

Initial analysis revealed that Groups A+, A+/A Exp, and A+/D Exp did not differ from each other in any phase of the experiment, largest F(2, 21) = 1.85. Therefore, subsequent analyses collapsed across these groups to form Group Control.

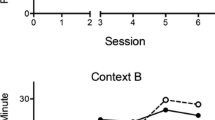

The results of acquisition and extinction are shown in Fig. 7. As expected, both groups increased their rates of leverpressing over the course of acquisition. A 2 (group: A+D+ vs. Control) × 6 (session) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of session, F(5, 150) = 40.62. No other main effects or interactions approached significance, largest F(1, 30) = 1.61.

Mean responding during 30-min sessions of acquisition and extinction in Experiment 4. A+D+, acquisition in Contexts A and D

During extinction, Group A+D+ generalized leverpressing to Context B more than did Group Control. A 2 (group: A+D+ vs. Control) × 4 (session) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session, F(3, 90) = 153.02 and a session × group interaction, F(3, 90) = 7.61. Separate ANOVAs revealed that Group A+D+ differed from Group Control on the first day of extinction, F(1, 30) = 7.98, but this difference had dissipated by the last day of extinction, F(1, 30) = 1.11.

The data from the renewal test are depicted in Fig. 8. At test, although both groups demonstrated a renewal effect, Group A+D+ showed greater renewal than did Group Control. A 2 (group: A+D+ vs. control) × 2 (context: extinction vs. renewal) ANOVA revealed a significant context effect, F(1, 30) = 27.22, and a significant context × group interaction, F(1, 30) = 7.10. The main effect of group was not significant, F(1, 30) = 1.20. Separate ANOVAs revealed that Group A+D+ differed from Group Control in the renewal context, F(1, 30) = 5.10, but not in the extinction context, F < 1. Paired t tests revealed an effect of context for both groups, minimum t(23) = 2.75. Thus, while both groups showed a significant renewal effect, Group A+D+ made significantly more leverpresses in Context C than did Group Control.

Results of the renewal test from Experiment 4: Mean responding during the 10-min test session in the extinction context (Context B) and the renewal context (Context C). A+D+, acquisition in Context A and D

Discussion

The results of Experiment 4 indicate that acquisition in multiple contexts increases the magnitude of ABC renewal. When acquisition of leverpressing occurred in Contexts A and D, responding at test was stronger than when acquisition occurred only in Context A. Interestingly, acquisition in multiple contexts also resulted in more responding during the extinction phase of the experiments, which is consistent with the different levels of renewal in suggesting that training in multiple contexts increased generalization to a new context.

General discussion

The present set of experiments examined renewal after the extinction of instrumental responding. In all studies, acquisition of leverpressing occurred in Context A, followed by extinction of leverpressing in Context B. Finally, testing occurred in both the extinction context and the renewal context. In some cases, the renewal context was the original context (ABA renewal), and in other cases it was a third context (ABC renewal). Experiment 1 examined whether the strength of ABC renewal depended on the amount of acquisition training. The results indicated that although tripling the amount of acquisition training had a demonstrable effect on responding in both acquisition and extinction, it did not influence the degree of responding during renewal testing. However, using a different configuration of chambers providing the contexts, in Experiment 2 we found that the amount of acquisition did have an effect on both ABA and ABC renewal. We hypothesized that the discrepancy between the results of Experiments 1 and 2 occurred because the chambers used as contexts in Experiment 1 promoted generalization of extinction to testing (Contexts B and C were modified versions of the same manufactured model), while the chambers used in Experiment 2 promoted generalization of acquisition to testing (A and C were the chambers previously used as B and C). Experiment 3 confirmed that ABA and ABC renewal were both stronger when extinction occurred in a relatively distinct context. In ABA renewal, the distinctive extinction context reduced the similarity of the extinction and test contexts; in ABC renewal, it also made the acquisition and test contexts more similar. The Experiment 3 results thus suggest that similarity of the test context to the extinction or to the acquisition context can strongly affect the strength of renewal. Finally, in Experiment 4, ABC renewal was increased when acquisition occurred in two contexts (A and D), as compared to training in one context (A). Thus, acquisition in multiple contexts also increases ABC instrumental renewal.

The present results extend the findings of Bouton et al. (2011) by demonstrating that instrumental renewal is affected by three important factors. One factor is the amount of acquisition training (Exp. 2). A second factor is the degree of similarity (and generalization) between the test and extinction contexts and the test and acquisition contexts (Exps. 1, 2, and 3). The third factor is acquisition in multiple contexts (Exp. 4), which was hypothesized to increase generalization from acquisition to test by allowing more stimulus components of the context to enter into the associative structure during acquisition. This should increase the likelihood that the test conditions would retrieve acquisition (Atkinson & Estes, 1963). A related effect has been observed in Pavlovian fear conditioning by Gunther, Denniston, and Miller (1998), who reported a reduction in ABC renewal when extinction occurred in multiple contexts (presumably by increasing the number of extinction context elements that were shared with the test context). Gunther et al. also showed that promoting generalization of acquisition (via acquisition in multiple contexts) counteracted this attenuation of renewal.

The role of generalization in instrumental renewal is also consistent with other findings from Pavlovian fear conditioning. For example, Thomas, Larsen, and Ayres (2003, Exps. 1a and 1b) demonstrated strong ABA renewal in rats when contexts were distinguished on the basis of odor cues and the location of boxes (as well as unintended physical differences between copies of the same box), but they did not observe renewal when contexts were distinguished only on the basis of the location of boxes (and unintended differences). Presumably, varying the contexts on many factors made the contexts more distinct, resulting in stronger renewal. Similarity of contexts has also been shown to affect ABA renewal in humans (Bandarian Balooch & Neumann, 2011; Havermans, Keuker, Lataster, & Jansen, 2005). In these experiments, ABA renewal was weaker when Contexts A and B were similar, and stronger when the contexts were manipulated to be more distinct. Thus, in Pavlovian conditioning with both humans and rats, similarity between contexts has been shown to attenuate ABA renewal. The present results expand on these findings and extend them to ABA and ABC renewal following the extinction of an instrumental response.

It is worth noting that all three of the variables that were shown here to increase the strength of renewal are likely to strengthen renewal in the world outside the laboratory. For example, the smoker, drinker, or overeater typically performs his or her problem behaviors for many years and in many contexts. Thus, one should be careful not to underestimate the importance of effects like ABC renewal in potentially making problematic instrumental behaviors persistent and difficult to eliminate.

Why does instrumental renewal occur at all? The fact that removal from the extinction context results in an increase in responding has suggested that instrumental extinction partly involves some form of context-specific inhibition (Bouton et al., 2011). Because this inhibition is relatively context specific, testing outside the extinction context allows responding to return to some degree. One way to characterize extinction learning is as an inhibitory S–R association that suppresses responding in the extinction context (Rescorla, 1993, 1997). Alternatively, the extinction context might act as a negative occasion setter (see Bouton et al., 2011). In this case, the context would signal a response–no reinforcer relationship. This occasion-setting mechanism is consistent with Pavlovian studies that have failed to detect inhibition in the extinction context (see Bouton & King, 1983; Bouton & Swartzentruber, 1986). Although the present experiments do not directly test for the specific mechanism, it should be noted that some aspects of the data do not seem consistent with inhibitory S–R learning. For example, in Experiment 4, the group that received acquisition in two contexts (Group A+D+) responded more during extinction than did the control group. This could have resulted in a stronger S–R association, leading to greater suppression of responding at test (Rescorla, 2001). However, it was this group that showed more responding during the renewal test. Related results have been found in Pavlovian conditioning, where high levels of responding during extinction have correlated with more, rather than less, responding during renewal tests (Bouton, García-Gutiérrez, Zilski, & Moody, 2006) and spontaneous recovery tests (Moody, Sunsay, & Bouton, 2006). It should also be noted that the evidence that similarity between the acquisition and test contexts is important (e.g., Exp. 3) suggests that learning about the acquisition context, and not just the extinction context, also influences instrumental renewal. Context A might promote responding by directly activating a representation of the reinforcer or by acting as a positive occasion setter (cf. Bouton et al., 2011, Exp. 4). Either of these mechanisms could have supported strong responding after extinction when the animal was returned to Context A or tested in a third context that generalized to Context A.

At the most basic level, the present experiments provide further evidence that extinction does not result in the erasure of original learning. Instead, extinction of instrumental behaviors appears to be relatively context specific, as evidenced by the return of responding when testing occurs outside the context of extinction. The results imply a strong parallel between Pavlovian extinction and instrumental extinction. They also have methodological, theoretical, and clinical implications. At the methodological level, it is clear that the choice of contexts can greatly influence the strength of any renewal effect. Although full counterbalancing should reduce any effect attributable to particular experimental chambers, some configurations of chambers will promote strong levels of renewal, while others should promote less. It is thus risky to infer the strength of a renewal effect (e.g., ABC renewal) from the size of the effect in a single experiment. At the theoretical level, the findings suggest that responding at test is strongly influenced by generalization between contexts. This generalization can be due to either the inherent physical properties of the contexts or to generalization promoted through experience (Exp. 4). Clinically, the results suggest that extinction of instrumental behaviors does not eliminate them permanently. Instead, these behaviors are readily revealed by a change of context after extinction. In addition, instrumental behaviors that have had extensive histories of reinforcement (Exp. 2) and/or reinforcement in multiple contexts (Exp. 4) may be especially prone to renewal. However, the data also confirm (see also Thomas et al., 2003) that it is possible to attenuate relapse (i.e., renewal) by conducting extinction in a context that is similar to the test context.

References

Atkinson, R. C., & Estes, W. K. (1963). Stimulus sampling theory. In R. D. Luce, R. B. Bush, & E. Galanter (Eds.), Handbook of mathematical psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 121–268). New York: Wiley.

Bandarian Balooch, S., & Neumann, D. L. (2011). Effects of multiple contexts and context similarity on the renewal of extinguished conditioned behavior in an ABA design with humans. Learning and Motivation, 42, 53–63.

Bossert, J. M., Liu, S. Y., Lu, L., & Shaham, Y. (2004). A role of ventral tegmental area glutamate in contextual cue-induced relapse to heroin seeking. Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 10726–10730.

Bouton, M. E. (2002). Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: Sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 976–986. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01546-9

Bouton, M. E. (2004). Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning and Memory, 11, 485–494. doi:10.1101/lm.78804

Bouton, M. E. (2011). Learning and the persistence of appetite: Extinction and the motivation to eat and overeat. Physiology and Behavior, 103, 51–58.

Bouton, M. E., García-Gutiérrez, A., Zilski, J., & Moody, E. W. (2006). Extinction in multiple contexts does not necessarily make extinction less vulnerable to relapse. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 983–994. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.07.007

Bouton, M. E., & King, D. A. (1983). Contextual control of the extinction of conditioned fear: Tests for the associative value of the context. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Animal Behavior Processes, 9, 248–265. doi:10.1037/0097-7403.9.3.248

Bouton, M. E., & Ricker, S. T. (1994). Renewal of extinguished responding in a second context. Animal Learning & Behavior, 22, 317–324.

Bouton, M. E., & Swartzentruber, D. (1986). Analysis of the associative and occasion-setting properties of contexts participating in a Pavlovian discrimination. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Animal Behavior Processes, 12, 333–350. doi:10.1037/0097-7403.12.4.333

Bouton, M. E., Todd, T. P., Vurbic, D., & Winterbauer, N. E. (2011). Renewal after the extinction of free operant behavior. Learning & Behavior, 39, 57–67. doi:10.3758/s13420-011-0018-6

Chaudri, N., Sahuque, L. L., & Janak, P. H. (2009). Ethanol seeking triggered by environmental context is attenuated by blocking dopamine D1 receptors in the nucleus accumbens core and shell in rats. Psychopharmacology, 207, 303–314.

Crombag, H. S., & Shaham, Y. (2002). Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience, 116, 169–173.

Everitt, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2005). Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: From actions to habits to compulsion. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 1481–1489. doi:10.1038/nn1579

Gunther, L. M., Denniston, J. C., & Miller, R. R. (1998). Conducting exposure treatment in multiple contexts can prevent relapse. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 75–91. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10019-5

Hamlin, A. S., Clemens, K. J., & McNally, G. P. (2008). Renewal of extinguished cocaine-seeking. Neuroscience, 151, 659–670.

Hamlin, A. S., Newby, J., & McNally, G. P. (2007). The neural correlates and role of D1 dopamine receptors in renewal of extinguished alcohol-seeking. Neuroscience, 146, 525–536.

Havermans, R. C., Keuker, J., Lataster, T., & Jansen, A. (2005). Contextual control of extinguished conditioned performance in humans. Learning and Motivation, 36, 1–19.

Moody, E. W., Sunsay, C., & Bouton, M. E. (2006). Priming and trial spacing in extinction: Effects on extinction performance, spontaneous recovery, and reinstatement in appetitive conditioning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59, 809–829. doi:10.1080/17470210500299045

Nakajima, S., Tanaka, S., Urushihara, K., & Imada, H. (2000). Renewal of extinguished lever-press responses upon return to the training context. Learning and Motivation, 31, 416–431.

Rescorla, R. A. (1993). Inhibitory associations between S and R in extinction. Animal Learning & Behavior, 21, 327–336.

Rescorla, R. A. (1997). Response-inhibition in extinction. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 50B, 238–252.

Rescorla, R. A. (2001). Experimental extinction. In R. R. Mowrer & S. B. Klein (Eds.), Handbook of contemporary learning theories (pp. 119–154). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rescorla, R. A. (2008). Within-subject renewal in sign tracking. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61, 1793–1802. doi:10.1080/17470210701790099

Thomas, B. L., Larsen, N., & Ayres, J. B. (2003). Role of context similarity in ABA, ABC, and AAB renewal paradigms: Implications for theories of renewal and for treating phobias. Learning and Motivation, 34, 410–436.

Zironi, I., Burattini, C., Aircardi, G., & Janak, P. H. (2006). Context is a trigger for relapse to alcohol. Behavioural Brain Research, 167, 150–155.

Author note

This research was supported by Grant R01 MH064847 from the National Institute of Mental Health. T.P.T. was partially supported by a graduate scholarship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). We thank Elena Molokotos for help running the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Todd, T.P., Winterbauer, N.E. & Bouton, M.E. Effects of the amount of acquisition and contextual generalization on the renewal of instrumental behavior after extinction. Learn Behav 40, 145–157 (2012). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13420-011-0051-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13420-011-0051-5