Abstract

Plausible personal events envisioned as occurring in the near future tend to be reported as more vivid than those set in the far future. Why is this? The present set of three experiments identified one’s familiarity with the location in which the event is placed as critical in this regard. Specifically, Experiment 1 demonstrated that amongst a wide range of phenomenological characteristics, clarity of location appears to drive the overall difference in vividness between events imagined to take place in the near and the far future. Experiments 2 and 3 were designed to further elucidate this finding. Experiment 2 demonstrated that near future events are more likely than far future events to be imagined in familiar locations. Experiment 3 showed that future events set in familiar locations tend to be imagined with greater clarity than those set in unfamiliar locations. The results of all three experiments converge on the conclusion that the difference in vividness of events imagined as occurring in the near and far future is mediated by one’s familiarity with the location in which the event is imagined to occur.

Similar content being viewed by others

Imagining hypothetical events that might occur in one’s future is a common experience. For example, during a particularly grueling workday, you may find yourself imagining being home with your family enjoying a quiet dinner. These imagined events are often accompanied by vivid details and a sense of preliving, or mentally traveling forward in time to preexperience the event. This capacity, termed episodic future thought (Atance & O’Neill, 2001; Szpunar, 2010), has been associated with the capacity to remember past episodes of one’s life (i.e., episodic memory;Footnote 1 Tulving, 1985). Indeed, Tulving has suggested that both episodic future thought and episodic memory are manifestations of an overarching capacity to be consciously aware of one’s continued existence in subjective time, namely “autonoetic consciousness.”

Evidence from multiple lines of research has suggested that the cognitive processes underlying episodic future thought are similar to those underlying episodic memory. The origin of this idea arose from Tulving’s (1985) observations of patient K.C., a man with global amnesia. K.C. lacked the capacity not only to remember specific events from his past, but also to imagine potential personal future events. Subsequent research has demonstrated this parallel deficit in other patients with amnesia arising from medial temporal lobe damage (Hassabis, Kumaran, Vann & Maguire 2007; Klein, Loftus & Kihlstrom 2002) and in populations with less profound memory impairments [e.g., those with depression (Williams, Ellis, Tyers, Healy, Rose and MacLeod 1996) and schizophrenia (D’Argembeau, Raffard & Van der Linden 2008), and older adults (Addis, Wong & Schacter 2008)]. Moreover, neuroimaging studies have shown a strong correspondence between brain regions associated with episodic future thought and those associated with episodic memory (Addis, Pan, Vu, Laiser & Schacter 2009; Addis, Wong & Schacter 2007; Szpunar, Chan & McDermott 2009; Szpunar, Watson & McDermott 2007).

In addition to the rapidly expanding neuropsychological and neuroimaging evidence for the close relationship between episodic future thought and episodic memory, behavioral experiments have demonstrated that the two capacities are similarly linked to individual differences in the capacity for visual imagery (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2006).

The purpose of the present research was to focus on one particularly interesting finding that has emerged from behavioral studies comparing episodic future thought with episodic memory. Specifically, we were interested in how the phenomenological characteristics of future thoughts vary with temporal distance from the present. D’Argembeau and Van der Linden (2004) initially reported that events imagined to occur in the near future (defined as between 1 month and 1 year from the present) are experienced as more vivid than those imagined as occurring farther in the future (defined as 5–10 years from the present). What is the source of this observation? It is well known that a similar pattern exists for episodic memory (i.e., older memories are less vivid than more recent memories), but why does this influence of temporality extend to future thought? Why do imagined events that have not yet been experienced (in the near or the far future) differ in their phenomenological qualities as a function of temporal placement?

In our first experiment, we fleshed out the temporal distance from the present such that five levels of the variable were instantiated (cf. the near/far distinction in the prior work). Like D’Argembeau and Van der Linden (2004), we examined various (12) phenomenological characteristics of episodic future thought (and remembering). In a departure from the prior work, however, we manipulated the temporal distance from the present between participants to avoid any potential influence of demand characteristics (which might have been especially salient with the five temporal distances). For example, participants might assume that events occurring within the next week should differ systematically from those occurring a month or a year from now.

To foreshadow, among the 12 phenomenological characteristics explored in Experiment 1, the clarity of the imagined location emerged as particularly important. Experiments 2 and 3 followed up on this finding by examining the role that one’s familiarity with the imagined location may have contributed to this observation. Specifically, Experiment 2 tested the hypothesis that location familiarity in imagined future events differs across different temporal distances (i.e., events imagined in the more distant future are situated within less familiar locations). Experiment 3 elucidated the influences of temporal distance and location familiarity on the clarity with which location is experienced during episodic future thought. The results of all three experiments suggest that episodic future thoughts in the near future are more vividFootnote 2 than those in the far future, in part because we tend to place near future episodes in known locations, which are envisioned more clearly than unknown locations.

Experiment 1

In this experiment, we examined which phenomenological characteristics differ between events imagined in the near and far future when temporal placement is manipulated at multiple levels. Additionally, temporality associated with remembering one’s past was also examined. In part, this additional manipulation (i.e., asking participants to recall memories from various life periods) provided an opportunity to replicate prior results with the present between-participants design, and thus adds to the literature showing a relation between temporal placement and vividness of remembering. More importantly, this additional manipulation provided an opportunity to better understand any effects associated with future thought.

Method

Participants

A total of 186 Washington University undergraduate students participated in exchange for class credit. Data from 26 participants were dropped from the analysis due to failure to follow instructions or a significant amount of missing data.

Design

A 2 × 5 mixed design was used, with temporal orientation (future and past) as a within-participants factor and temporal distance [1 day (n = 32), 1 week (n = 32), 1 year (n = 31), 5 years (n = 31), and 10 years (n = 34)] as a between-participants factor. Temporal distance was manipulated between participants so that phenomenological ratings could not be based on comparisons across temporal distances or on naïve theories of how the vividness of future events and memories set at different temporal distances should vary. This design decision is discussed further in the General Discussion.

Materials

A modified version of the Crovitz–Shiffman cuing technique was used (Crovitz & Schiffman, 1974). One-word cues (e.g., mother, lake, city) were used as starting points for imagining/remembering future and past events (cf. Szpunar & McDermott, 2008). The same set of 20 cues (adapted from Rubin, 1980) was used in each condition. On a participant-by-participant basis, random assignment was used to pair cues to a temporal orientation and to determine the cue order.

To measure phenomenological characteristics, 12 questions (commonly used in assessing the relation between episodic future thought and episodic memory; see, e.g., D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004, 2006; Szpunar & McDermott, 2008) were adapted from the Memory Characteristics Questionnaire (MCQ; Johnson, Foley, Suengas & Raye 1988). Each future thought and each memory was rated by each participant on each of the 12 questions, which probed the following characteristics: feelings of mentally traveling backward or forward in time (1 = not at all, 7 = completely), sound (1 = little, 7 = a lot), effort required to bring the event to mind (1 = very easy, 7 = very effortful), feelings of pre- or reexperiencing the event (1 = not at all, 7 = completely), clarity of location (1 = vague, 7 = clear), envisioning or remembering bodily movements (1 = not at all, 7 = completely), clarity of the spatial arrangement of objects (1 = vague, 7 = clear), clarity of the spatial arrangement of people (1 = vague, 7 = clear), smell/taste (1 = little, 7 = a lot), degree to which the event is remembered or imagined as a coherent story (1 = not at all, 7 = completely), clarity of time of day (1 = vague, 7 = clear), and visual details (1 = few, 7 = a lot).

Procedure

The experimenter read detailed instructions to the participants, who were told that they would be imagining possible future episodes they might experience, remembering episodes from their past, and answering questions about these imaginations/recollections. The experimenter explained that each future thought/memory should be of an event that will be/was specific and discrete in time, lasting no more than a few hours. Verbal descriptions of two sample events—one in the future and one in the past—were provided. The example future event described riding in a car with friends, and the example past event described taking a test. Both sample events included details such as the settings, other people, visual and auditory details, and emotions (see Appx. A for the complete instructions).

Furthermore, participants were instructed that the event contained in each future thought (or memory) should occur (or should have occurred) at a specific temporal distance from the present. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of five temporal conditions: within 1 day; approximately 1 week, 1 year, or 5 years; or at least 10 years from the present. All future events and memories had to be within the assigned time frame.

At the beginning of each trial, participants were instructed via temporal orientation cues (future, past) presented on the screen either to imagine a future event or to remember a past event. Future and past trials occurred in a random order determined on a participant-by-participant basis, with no more than two of the same trial type occurring in a row. A randomly paired word cue (e.g., lake) was also presented on the screen. Participants were told that they could use the word cue to help them think of a future event or memory, but that their event did not have to be related to the word cue in any direct way. In addition, on every trial the appropriate temporal distance (e.g., within 1 week) was presented on the screen to remind participants of the time period from which they were to imagine/remember events. The temporal orientation cue, word cue, and temporal distance reminder remained on the screen until after participants finished describing the event.

Once they had a future event or memory in mind, participants pressed the space bar. While the cues and the temporal distance reminder were still displayed, the background color of the screen turned green for 3 min. During that time, participants wrote a description of their future thought/memory in a booklet. Participants were instructed to record as many details as possible and, in particular, to write as many details as they could imagine (or remember) about where they would be (or were) and who and what would be (or was) around them. After 3 min, the screen color changed to red and the cues and reminder were removed from the screen to signal participants to stop writing. After the participants had completed the experiment, the written protocols were reviewed to ensure that participants had followed the instructions. Fifteen participants were excluded due to failure to follow instructions. See Appendix B for sample past and future written protocols.Footnote 3

Immediately after the 3-min writing period for an event, participants answered a series of 12 questions about their phenomenological experiences of that immediately preceding future thought (or memory). One question was presented on the screen at a time, and questions were always presented in the same order. Participants responded by pressing the appropriate number key on the keyboard. Both the participants’ responses and response latencies were recorded. The trial ended after the twelfth rating had been made. Any response made under 600 ms was assumed to be invalid and was not included in the results. If more than 10% of any participant’s responses were under 600 ms, that participant was excluded from the results. Nine participants were excluded in this manner. Two other participants were excluded from the results because their average response times were more than two standard deviations below the group mean.

Prior to the experimental trials, participants completed two practice trials to ensure that they understood the instructions. After the two practice trials, participants were given an opportunity to ask questions. They then completed 20 experimental trials consisting of 10 future and 10 past trials. After the participants had completed all 20 experimental trials, 147 of the 186 participants completed a short questionnaire designed to characterize individual differences in time orientation (the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Those data will not be considered here. Participants were then debriefed and thanked for their time. The experiment lasted approximately 2 h.

Results and discussion

We examined 12 phenomenological ratings for future thoughts (and memories) at the various temporal distances. Although our focus was on any rating differences arising in relation to near and distant future events, data for the memory ratings were considered for two reasons. First, we aimed to replicate commonly reported relations between future and past thought in terms of such ratings (e.g., memories are typically more vivid than future thoughts; cf. D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004). Second, considering the results of both future thoughts and memories would offer interpretive leverage on any differences identified between near and distant future thoughts. That is, having also considered the pattern of results emerging with memories would address whether such differences were unique to future thinking or were similarly manifested during remembering.

Phenomenological qualities

Mean responses to each of the 12 phenomenological questions can be seen in Table 1. These data were analyzed using a series of 2 (temporal orientation) × 5 (temporal distance) mixed ANOVAs (24 in all). In an attempt to balance the exploratory nature of the experiment with the presence of 24 independent ANOVAs, a criterial alpha level of .01 was adopted.Footnote 4 Eta squared (η 2) is reported as a measure of effect size; η 2 indicates the proportion of unique variance accounted for by each factor. Unlike η 2p , when calculating η 2, the denominator (SStotal) is consistent across effects allowing for direct comparisons of effect sizes from the same analysis.

These data were used to answer three main questions: (1) Can we replicate previous findings that memories of past events are generally more vivid than thoughts about future events (main effect of temporal orientation)? (2) Which (if any) phenomenological qualities in future thoughts are affected by temporal distance (i.e., which show a simple main effect of temporal distance for future thoughts)? And, (3) Does temporal distance affect future thoughts and memories differently (i.e., do any qualities show an interaction between temporal orientation and temporal distance)? Below, each question is discussed separately.

Temporal orientation: differences between episodic memories and episodic future thoughts

In an effort to validate our approach of using a mixed (i.e., a between- and within-participants design), we first examined main effects of temporal orientation. In particular, we were interested in whether we could replicate the well-known finding that memories of past events are generally experienced more vividly than thoughts about future events.

Indeed, many of the responses to the phenomenological questions revealed a similar pattern indicating that memories of past events are generally more vivid than specific thoughts about the future (see Table 1). Questions relating to clarity of location, clarity of time of day, feelings of mentally traveling forward or backward in time, feelings of re- or preexperiencing the event, clarity of spatial arrangement of people, clarity of spatial arrangement of objects, degree to which the event is remembered or imagined as a coherent story, and visual details were given higher ratings during remembering than during future thought. For all of these questions, there was a main effect of temporal orientation: smallest F(1, 155) = 24.29, p < .001, η 2 = .13.

Also shown in Table 1, the question related to the effort required to bring an event to mind showed the opposite pattern; for this question, thoughts about future events were given a higher rating than memories of past events, F(1, 155) = 35.02, p < .001, η 2 = .18, indicating that more effort was required to bring a future event to mind than to remember a past event.

Temporal distance: differences between near and far future events

As can be seen in Table 1, only one phenomenological quality, clarity of location, exhibited an overall main effect of temporal distance, F(4, 155) = 9.35, p < .001, η 2 = .19 (see Fig. 1). That is, the clarity of the imagined or remembered location was greater for thoughts about temporally near events (e.g., 1 day, M = 6.09) than for thoughts about temporally distant events (e.g., 10 years, M = 5.42).

Of particular importance was the simple main effect of temporal distance on future thoughts. As can be seen in Table 1, location clarity decreased from 1 day (M = 5.88) to 10 years (M = 4.93) for thoughts about future events. For this reason (and as will be further justified by a significant interaction, see below), we conducted a one-way ANOVA to examine the effect of temporal distance on the location clarity of future thoughts. This analysis indicated that location was reliably clearer for temporally near future thoughts than for far future thoughts, F(4, 155) = 11.80, p < .001, η 2 = .23. Because clarity of location was the only phenomenological quality with a main effect of temporal distance for future thoughts, this quality appears to be particularly important.

Interaction between temporal orientation and temporal distance

Although our main interest was the finding that the clarity of location was greater for thoughts about near than about far future events, there was a similar effect of temporal distance for memories. That is, the clarity of location was greater for temporally near memories (e.g., 1 day, M = 6.29) than for far memories (e.g., 10 years, M = 5.92), F(4, 155) = 3.70, p = .007, η 2 = .09.

A significant temporal orientation by temporal distance interaction, F(4, 155) = 7.49, p < .001, η 2 = .08, indicated that the effect of temporal distance found for thoughts about future events is larger than the effect found for memories. That is, the enhanced clarity of near (relative to far) temporal distances was more pronounced for future thoughts than for memories; the interaction could also be interpreted as showing that the difference in clarity of location between future thought and remembering increases as temporal distance from the present increases (see Fig. 1).

The larger effect of temporal distance on location clarity in future thoughts than in memories can be quantified by examining the effect sizes in the two one-way ANOVAs. These ANOVAs indicated that location was clearer in near than in far future events and in near than in far memories. However, the difference in effect sizes (future events, η 2 = .23; memories, η 2 = .09) indicates that temporal distance had a greater influence on location clarity in future thoughts than in memories. In addition, two independent-samples t tests comparing location clarity of near events (i.e., means for 1 day and 1 week) and far events (i.e., means for 5 and 10 years) showed a decrease in location clarity with increasing temporal distance for both future thoughts, t(127) = 6.34, p < .001, d = 1.13, and memories, t(127) = 2.63, p = .009, d = 0.47. The difference in effect size again indicates that the decrease was more pronounced in future thoughts.

A final note regards the observation that the location clarity ratings for memories of past events are high on the scale, which may indicate a ceiling effect that would cloud interpretation of this interaction. The small standard errors assuage this worry somewhat. In addition, the data were subjected to a median split, and ANOVAs were conducted on the data above and below the median. The interaction was significant for both sets of data. The presence of a significant interaction for the data below the median, which were well below ceiling (past M = 5.72), indicates that this interaction is not the result of a scaling issue.

Summary

In general, a similar pattern of ratings was obtained for most of the phenomenological qualities: ratings were higher (e.g., greater clarity) for past than for future events in 8 of the 12 questions. Effort required to bring an event to mind showed the opposite pattern, indicating that future events required more effort than past events to imagine/remember. These data replicate previous findings (cf. D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004).

In contrast, events more temporally near the present were given higher ratings in only 1 of the 12 questions (clarity of location), suggesting that farther temporal distances were not associated with a uniform decrease in event vividness. Instead, clarity of location emerged as being particularly important. In addition, a significant temporal distance by temporal orientation interaction found in clarity of location demonstrates that, although both near future events and near memories are rated as having greater clarity of location than far future events and far memories, respectively, this difference is more pronounced for episodic future thought than for episodic memory.

Might this difference in the clarity of location underlie the finding that near future events tend to be more vivid overall than temporally distant future events (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004)? Experiments 2 and 3 explored this hypothesis by trying to understand why the clarity of location in future events imagined to take place in the near future is rated as more vivid than clarity of location in distant future events, despite the fact that future events imagined at all temporal distances have not yet occurred. Specifically, Experiment 2 examined whether—in episodic future thought—temporally near events tend to more often be placed in previously experienced familiar settings (relative to temporally distant events). Experiment 3 expanded upon this approach by examining how temporal distance and location familiarity covary in episodic future thought.

Experiment 2

Memories must be set in previously experienced locations. However, future events could be imagined in either previously experienced (familiar) locations or novel (unfamiliar) locations. Could this difference explain why temporal distance has such a large effect on the clarity of location in future events? For instance, are temporally near future events typically envisioned in previously experienced locations, and are temporally distant future events less often envisioned in familiar locations? Experiment 2 sought to answer these questions. Consider an example: Undergraduates imagining themselves in their bedroom in 1 week are likely to imagine their current bedroom. However, if those same undergraduates imagine themselves in their bedroom in 5 years, they may imagine that they are in a future, currently unknown bedroom. According to the reality-monitoring theory (Johnson, Hashtroudi & Lindsay 1993; Johnson & Raye, 1981), images based on memories are more vivid than those based on imagination, and therefore, future thoughts set in previously experienced locations may be more vivid than those set in unfamiliar locations. Therefore, if participants are more likely to set future thoughts in unfamiliar locations when the event is in the more distant future, location familiarity may be the reason why there is less clarity of location for more distant future events. The present experiment tested the idea that events set farther in the future are more likely to be placed in unfamiliar locations.

Method

Participants

A group of 49 Washington University undergraduate students participated in exchange for class credit. Data from 3 participants were not included in the analysis due to technical errors. Of the remaining 46 participants, 23 participated in each of the two conditions.

Design

The experimental design included one between-participants independent variable with two levels (temporal distance: 1 week, 5 years). A between-participants manipulation was again used to avoid influence from potential preexperimental biases. This design is a simplified version of Experiment 1, designed to focus on a specific question and follow up on the finding that temporal distance is associated with a greater decrease in the clarity of location in future thoughts than in memories. The question focuses on why this decrease is found in future thoughts; therefore, participants were asked only to imagine future events, not to remember. A period of 5 years, rather than 10, was chosen as the far temporal distance because Experiment 1 found that the results for 10 years did not always follow the trends found at other temporal distances, which is perhaps attributable (at least in part) to the age of the participants.

Materials

A modified version of the Crovitz–Shiffman cuing technique was again used (Crovitz & Schiffman, 1974). In each condition, the same set of 48 one-word cues (adapted from Rubin, 1980; e.g., mother, chicken) was used. No words that could denote a location (e.g., city) were used as cues. The cues were randomly ordered on a participant-by-participant basis.

Three questions were asked at the end of each trial: “Where will this event take place?” (participants typed the answer); “Have you been to this location before?” (yes or no response); and “How familiar are you with this location?” [answered on a scale from 1 (unfamiliar) to 7 (very familiar)].

Procedure

Participants read all instructions on the computer. They were told that they would be imagining possible future episodes that they might experience and answering questions about their representations of these events. They were told that each event should be set either 1 week or 5 years in the future, depending on the condition (manipulated between participants). As in Experiment 1, participants were told that they should imagine events that were specific and discrete in time, and an example of an appropriate event was provided.

The experiment consisted of 48 trials. At the beginning each trial, a cue was presented on the screen for 20 s, during which time participants were to imagine a future event. After the 20 s, the cue was followed by three questions. First, participants were asked to type the location of the event as a way to focus participants on a particular location. They were then asked two additional questions: “Have you been to this location before? (y = yes, n = no)” and “How familiar are you with this location on a scale from 1 (unfamiliar) to 7 (very familiar)?”. Prior to beginning the experimental trials, participants completed 2 practice trials to ensure that they understood the instructions. The whole experiment lasted approximately 30 min.

Results and discussion

Responses to the question “Where will this event take place?” were used as a way to orient participants to one location per event, and therefore the results from this question were not analyzed. Responses to the question “Have you been to this location before?” were analyzed using a chi-square test, and responses to the question “How familiar are you with this location?” were analyzed using an independent-samples t test. The alpha level for all analyses was set at .05.

As will be seen, responses to both questions indicated that events set in the near future were more likely to be placed in familiar locations than were events set in the far future.

Have you been to this location before?

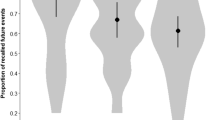

As can be seen in Fig. 2 (left), events set in the near future (M = 86.6%) were more likely than events set in the far future (M = 59.5%) to be placed in locations the participants had actually been to. This impression is quantified by a significant chi-square test, χ 2(1) = 205.7, p < .001.

Mean proportions of yes responses to the question “Have you been to this location before?” in the near and far future conditions, and mean responses to the question “How familiar are you with this location?” in the near and far conditions in Experiment 2. Error bars represent standard errors of the means

How familiar are you with this location?

As can be seen in Fig. 2 (right), when events were set in the near future, participants were more familiar with the event locations than when events were set in the far future (Ms = 5.07 and 3.87, respectively). This impression is quantified by a significant difference between mean responses in the near and far conditions, t(44) = 4.86, p < .001, d = 1.43.

Summary

Events set in the near future are more likely to be envisioned in familiar locations than are those set in the far future. Hence, the finding (in Exp. 1) that temporal distance exerted an effect on clarity of location can likely be attributed to the tendency of people to place near future events in familiar locations more often than they do far future events. That is, time per se is likely not the causal factor (cf. McGeoch, 1932); the variation in location familiarity that occurs with time may underlie part or all of this effect. To explore these ideas further, Experiment 3 examined the separate effects of temporal distance and location familiarity on the clarity of location in episodic future thought.

Experiment 3

In Experiment 1, the clarity of location for episodic future thoughts (and memories) was greater the closer the event was to the temporal present. Experiment 2 demonstrated that near future events are more likely to be set in familiar locations than are far future events. Experiment 3 addressed whether a direct manipulation of location familiarity (via instructions and event cues) would influence the clarity of location for episodic future thought. Furthermore, temporal distance was again manipulated (between 1 week and 5 years). If location familiarity completely underlies the effect of temporal distance on location clarity, controlling location familiarity should remove any effect of temporal distance. If, however, location familiarity is not a complete explanation for the effect of temporal distance on location clarity, a main effect of temporal distance might remain.

Method

Participants

A group of 179 Washington University undergraduate students participated in exchange for class credit. Data from 19 participants were dropped from the analysis due to failure to follow instructions (n = 4), a significant amount of missing data (n = 13), or technical errors (n = 2). Of the remaining 160 participants, 40 participated in each of the four conditions.

Design

A 2 (temporal distance: 1 week, 5 years) × 2 (location familiarity: familiar, unfamiliar) between-participants design was used. The variables were again manipulated between participants to avoid potential contamination from preexperimental biases. As in Experiment 2, all events were set in the future.

Materials

A modified version of the Crovitz–Shiffman cuing technique was again used (Crovitz & Schiffman, 1974). There were 48 cues per condition, and each cue was a one- to three-word phrase. In the familiar condition, all cues were common locations (e.g., dorm, library). In the unfamiliar condition, all cues were either locations participants were unlikely to have been to (e.g., Dead Sea, Pyramids of Egypt) or activities they were unlikely to have done (e.g., taming a lion, skydiving). The cues appeared in a random order on a participant-by-participant basis and were adopted from Szpunar et al. (2009).

One phenomenological question was adapted from the MCQ: “My representation for the location where the event takes place is:”, answered on a scale from 1 (vague) to 7 (clear). This question was asked at the end of each trial and was included as a dependent variable measure of clarity of location. In Part 2 of the experiment, as explained below, participants gave two additional responses: “Have you been to this location/participated in this activity before?” (yes or no response) and “Rate the ease of imagining an event in a familiar/unfamiliar location using this cue” [from 1 (very easy) to 7 (very difficult)]. The first question was included as a manipulation check to verify that participants had or had not been to the location before, as was appropriate for the condition. The second question was included to verify that any differences found in clarity of location were not due to differences in the difficulty of imagining locations.

Procedure

Participants read all instructions on the computer. They were told that they would be imagining possible future episodes that they might experience and answering questions about their representations of these events. As in Experiments 1 and 2, they were asked to imagine events that were specific and discrete in time, and an example of an appropriate event was provided.

Participants were told that each event should be set either 1 week or 5 years in the future, depending on the condition (manipulated between participants). In addition, participants were instructed to place events in either familiar or unfamiliar locations (again, between participants). In the familiar condition, participants were instructed to place the event in a location they had actually been to before. For instance, if the cue was dorm, the event could be located in a dorm that they had been to before. In the unfamiliar condition, participants were instructed to place the event in a location that they had not actually been to before. For instance, if the cue was Pyramids of Egypt, the event could be located in a desert in Egypt that they had never been to before. As in Experiments 1 and 2, participants were told that they should use the cue to help them think of a future event, but that their event did not have to be related to the cue in any direct way.

The experiment consisted of two parts, each containing 48 trials. In the first part, a trial consisted of a cue presented on the screen for 20 s, during which time participants were to imagine a future event. The cue period was followed by a question asking participants to rate the clarity of the location in that event. Prior to beginning Part 1, participants completed two practice Part 1 trials to ensure that they understood the instructions. After this part was complete, all cues were presented again in Part 2. For each cue, participants gave two additional responses: “Have you been to this location/participated in this activity before? (y = yes, n = no)” and “Rate the ease of imagining an event in a familiar/unfamiliar location using this cue on a scale from 1 (very easy) to 7 (very difficult).”

Any trials in the familiar condition in which participants indicated that they had not been to the location before were excluded from the analysis. Likewise, any trials in the unfamiliar condition in which the participants indicated that they had been to/participated in the cue before were excluded from the analysis. If more than 20% of any participant’s responses were excluded, the participant was excluded from the final analysis. Fifteen participants were excluded in this manner. In addition, 2 participants were excluded because their responses indicated that they were not following instructions (e.g., said that they had never been to a house before), and 2 participants were excluded due to technical errors.

After finishing the experiment, participants were debriefed and thanked for their time. The experiment lasted approximately 30 min.

Results and discussion

Phenomenological qualities

Responses to the clarity-of-location and ease-of-imagining-an-event questions were analyzed using 2 (location familiarity) × 2 (temporal distance) univariate ANOVAs. The alpha level was set at .05.

To preview, events set in familiar locations were rated as having greater clarity and being easier to imagine than those set in unfamiliar locations.

Clarity of location

As can be seen in Fig. 3, envisioning potential future events in familiar locations is associated with greater clarity of location than envisioning such events in unfamiliar locations (M = 5.46 and 4.65, respectively). In addition, clarity of location is greater for events set in the near (M = 5.22) than in the far (M = 4.89) future. These impressions were quantified by the presence of two main effects: F(1, 156) = 52.82, p < .001, η 2 = .24, for location familiarity, and F(1, 156) = 9.26, p = .003, η 2 = .04, for temporal distance. There was no significant interaction, F(1, 156) < 1.

Mean responses on clarity of location for events set in familiar and unfamiliar locations in the near and far future conditions in Experiment 3. Error bars represent standard errors of the means

Although both main effects were significant, the effect size for location familiarity exceeded that for temporal distance, indicating that location familiarity exerts a greater influence on the clarity of location than does temporal distance. According to standards set by Cohen (1988), the effect size for location familiarity exceeds the minimum necessary to be considered a large effect (η 2 = .14), whereas the effect size for temporal distance falls between the standards for small and medium effects (η 2 = .01 and .06, respectively). This difference in effect sizes indicates that although location familiarity cannot account for all of the differences in clarity of location in events set at varying temporal distances, it does account for a large proportion of the variance.

Ease of imagining an event

Events set in familiar locations (M = 2.80) were rated as easier to imagine than events set in unfamiliar locations (M = 3.60), F(1, 156) = 44.98, p < .001, η 2 = .22. In light of this finding, the clarity-of-location question was reanalyzed using ease of imagining as a covariate in order to ensure that the location familiarity effect was not simply due to differences in ease of imagining. No significant differences were found between the original analysis and the analysis using ease of imagining as a covariate, indicating that location familiarity had a unique effect on clarity of location.

Summary

Participants asked to envision future events in familiar locations reported greater clarity of location than those who imagined future events in unfamiliar locations. Furthermore, this pattern held both for participants asked to imagine events in the near future (1 week) and for those who imagined events in the far future (5 years). Temporal distance also had a separate effect on clarity of location; participants asked to imagine events in the near future reported clearer locations than did those who imagined events in the far future. Furthermore, this pattern held for participants who imagined events in both familiar and unfamiliar locations.

Although both location familiarity and temporal distance influenced clarity of location, the effect size was greater for location familiarity than for temporal distance. When this difference is interpreted in light of the results from Experiment 2 (that events set in the near future are more likely to be imagined in familiar locations), this difference in effect sizes becomes important. It suggests that location familiarity accounts for a large proportion of the variation in clarity of location that occurs when events are set at different temporal distances. In other words, although differences in location familiarity cannot explain all of the change in clarity of location (as is evident from the main effect of temporal distance), clarity of location is greater in near than in far future events in large part because near future events are more likely to be set in familiar locations.

General discussion

These experiments were designed to explore how the phenomenological qualities of episodic future thoughts vary with temporal distance from the present. Three main findings emerged. First, in Experiment 1, of the 12 phenomenological characteristics examined for episodic future thinking (and remembering) across five temporal distances, clarity of location was the only quality exhibiting a main effect of temporal distance. That is, temporally near events tended to have clearer locations than temporally far events, and, as indicated by a significant interaction between temporal orientation and temporal distance, this effect was greater for episodic future thoughts than for memories.

Second, a potential mechanism behind the influence of temporal distance on the clarity of location in episodic future thought was tested (Exp. 2). Specifically, the temporal placement of episodic future thought was manipulated to be in the near or the far future. Participants envisioning events within the next week were much more likely to set their events in familiar locations than were participants envisioning events in 5 years.

Third, Experiment 3 tested whether location familiarity underlies the effect of temporal distance on clarity of location. Events were manipulated to be placed in either familiar or unfamiliar locations and to be in either the near or the far future. Events set in familiar locations were clearer than events set in unfamiliar locations, and this effect persisted for events set in both the near and the far future. This result indicates that location familiarity underlies a large proportion of the effect of temporal distance on clarity of location. However, events set in the near future were clearer than events set in the far future for events placed in both familiar and unfamiliar locations. This effect indicates that location familiarity alone is not a complete explanation for the effect of temporal distance on clarity of location.

Together, these findings indicate that the greater clarity of location found in near future events (relative to far future events) can be accounted for in large part by differences in location familiarity. These findings, along with findings that will be discussed below (Szpunar et al., 2009), suggest that the contextual setting of events plays a large and important role in the connection between episodic future thought and episodic memory.

Design factors

The results from Experiment 1 deviate somewhat from the findings of D’Argembeau and Van der Linden (2004), who found an overall decrease in sensorial details and clarity of contextual information with increasing temporal distance in both future events and memories. In contrast, our Experiment 1 found a decrease in vividness with increasing temporal distance for only 1 out of 12 phenomenological qualities: clarity of location. D’Argembeau and Van der Linden’s (2004) results suggest that temporal distance has a uniform and profound effect on representations of future and past events, whereas the results from the present study suggest that the effect of temporal distance is more limited. Design differences between these experiments might account for the conflicting findings. D’Argembeau and Van der Linden’s (2004) experiment varied temporal distance within participants, whereas the present study varied temporal distance between participants. A within-participants design may make naïve theories about differences in the representations of temporally varied events salient (cf. Caruso, Gilbert & Wilson 2008; Koriat, Bjork, Sheffer & Bar 2004) in a way that might not naturally occur when people remember and imagine events in isolation from other events. For instance, participants may believe that events occurring closer to the temporal present should be more vivid. Once such naïve theories are salient, participants may use these theories rather than or in addition to their current representations to make vividness ratings. In contrast, outside of the experimental setting, at any one time people often remember or imagine events that are set only within a limited temporal distance (i.e., reminisce about college or yesterday’s meeting; imagine retiring to Florida or going to the dentist tomorrow). Remembering and imagining events within a limited temporal distance would not likely elicit naïve theories.

A study by Johnson et al. (1988) lends credence to this idea. They varied the temporal distance of autobiographical memories between participants; the vividness of the memories was assessed with the MCQ. Many sensorial details (e.g., sound, smell, and taste), some contextual details (e.g., the spatial arrangement of people), and overall clarity did not differ for distant and recent memories. The one quality found in the present study that had higher ratings in recent memories (clarity of location) also had higher ratings for recent memories in Johnson et al. (1988). Unlike the present study, however, a few additional questions (e.g., those regarding visual details and overall vividness) were also given higher ratings for recent memories in the Johnson et al. (1988) experiment. For the present purposes, the primary relevant finding is that when temporal distance was varied between participants, not all measures of vividness showed a decline with increasing temporal distance. The choice of whether temporal distance is manipulated between or within participants may play a role in the observed results, although future research that directly manipulates the two designs would be necessary for fully understanding these design issues.

Clarity of location and the role of familiar contextual settings

Clarity of location not only was the sole phenomenological quality showing a main effect of temporal distance in Experiment 1, it was also the only one to exhibit an interaction between temporal distance and orientation (past/future). Although the nearness of events was associated with clarity of location for both past and future events, this difference was more pronounced for future events. One potential mechanism is that, as we found in Experiment 2, near future events are more often set in familiar locations. Further, these results from Experiment 2 are consistent with Trope and Liberman’s (2003) theory of temporal construal: Near future events are represented in concrete, or low-level, construals, whereas distant future events are represented in abstract, or high-level, construals. According to Trope and Liberman, distant future events are represented in a general, decontextualized way because low-level details are often unreliable or unavailable. In line with this idea, in Experiment 2, participants more often reported setting near events in familiar locations and reported being less familiar with the locations of distant events. In other words, the details of locations in distant events were more likely to be unreliable or unavailable because participants had not actually been to those locations. However, the results from Experiment 3 indicate that the effect of location familiarity is more important than the effect temporal distance on clarity of location; unreliable or unavailable details result in less clarity of location, no matter when the event is imagined to occur.

One could hypothesize that imagining future events in unfamiliar contexts could also affect the vividness of other phenomenological dimensions. For instance, unfamiliar contexts could lead one to also imagine unfamiliar people and objects. Why, then, was there no effect of temporal distance found for these phenomenological qualities in Experiment 1? This lack of an effect could be due to the wording of the questions. Participants were asked to rate the clarity of the spatial arrangement of people and objects rather than the vividness of the people and objects themselves. Perhaps participants were able to consistently imagine the spatial arrangement of the people and objects in their future events, despite varying familiarity. Had participants rated the vividness of the people and objects themselves, an effect of temporal distance (due to varying familiarity) might have been found. Further research is needed to fully understand the possible effects of familiarity on other phenomenological qualities.

The finding that events set 5 years in the future are more likely to be placed in unfamiliar locations, relative to those set 1 week in the future, should be put into the context of the characteristics of the participants. All participants were young adult college students who are likely to move to a different city or living arrangement after college, and therefore will have drastically different surroundings within the next 5 years. If older, more settled adults were to be tested, they might be less likely to report placing future events that could occur in the next 5–10 years in unfamiliar locations. However, if the temporal distance were lengthened to include future events occurring in the next 20, 30, or 40 years, the same pattern would likely be found; the farther from the temporal present future events are imagined to take place, the more likely those events are to be imagined in unfamiliar locations.

The importance of the results from Experiment 2 becomes even more apparent when they are taken in conjunction with the results from Experiment 3, which demonstrated that representations of future events set in familiar locations have greater clarity of location relative to events set in unfamiliar locations. This difference was found in both near and far future events. Greater clarity of location for familiar locations across temporal distances is consistent with the reality-monitoring theory (Johnson et al., 1993; Johnson & Raye, 1981). This theory states that images based on experience are more vivid than images based on imagination. Images of familiar locations are likely based on experience, whereas images of unfamiliar locations are likely based on imagination, and according to the reality-monitoring theory, this difference could account for the variation in clarity of location.

The importance of familiar locations in episodic future thought is consistent with Szpunar et al.’s (2009) findings that the high degree of similarity in brain activity for episodic future thinking and remembering is limited to situations in which known contextual settings are utilized for episodic future thought. When participants imagined future events in familiar locations, their brain activity as measured by fMRI was largely the same as when they were remembering past events of their lives. This observation replicates a pattern found in several other experiments (Addis et al., 2007; Szpunar et al., 2007). Importantly, though, when participants imagined future events in unfamiliar locations, the similarity in brain activity to remembering largely disappeared. These results, as well as those from Experiment 3, indicate that the extent to which memory is sampled to create future thoughts largely depends on the contextual setting (for a similar point of view, see Hassabis & Maguire, 2007).

The effect of location familiarity on location clarity found in Experiment 3 is even more impressive when we take into account that this experiment (as well as Exp. 2) used only between-participants manipulations. Although information about clarity of location is dependent solely on self-report, a form of introspection, reliable and consistent differences between conditions were found. These reliable differences were found despite the fact that participants were naïve not only as to the purpose of the experiment but also to the variables being manipulated.

Although these results show the importance of familiarity in the clarity of the locations envisioned, the results of Experiment 3 also demonstrate that location familiarity is not a complete explanation of why near future events are more vivid than far future events. In addition to the effect of location familiarity, there was also a main effect of temporal distance: Near future events were more vivid than far future events, and this effect was consistent for events set in both familiar and unfamiliar locations. There are many possible reasons why temporal distance would still have an effect on clarity of location even after familiarity is controlled. For instance, a familiar location may be imagined to change over time. For example, a college campus may be imagined to have new buildings, people, and/or landscaping in the distant future. In addition, near future events may involve more defined goals and more concrete tasks, and they may be more likely to happen as imagined, because there is less time for current plans to be disrupted (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004; Spreng & Levine, 2006; Trope & Liberman, 2003). All of these characteristics may affect location clarity.

Summary

In summary, these three experiments together demonstrate that in episodic future thought, location familiarity accounts for a large proportion of the decrease in vividness found as distance from the temporal present increases. When imagining events in the near future, contextual episodic memories are likely to be sampled to create vivid events. When imagining events in the far future, contextual settings are more likely to be formed from semantic knowledge rather than from familiar locations, resulting in less vivid events. These results indicate that contextual settings largely underlie the connection between episodic future thought and episodic memory.

Notes

Throughout this article, the term episodic memory refers to autobiographical memories that are linked to a particular place and time.

Clarity of location is one aspect of the overall vividness of a memory or an imagined future event. For this reason, the word clarity will be used when referring to location (or another phenomenological characteristic), and the word vividness will be used when discussing the overall vividness (typically in discussions of the possible implications of the results).

The content of these written protocols will not be characterized in this report.

Although a criterial alpha level of .01 was adopted in Experiment 1, no main conclusions would have changed had the more traditional alpha level of .05 been adopted. Further, had the more stringent criteria of .001 been adopted, no conclusions related to episodic future thoughts would have changed.

References

Addis, D. R., Pan, L., Vu, M., Laiser, N., & Schacter, D. L. (2009). Constructive episodic simulation of the future and the past: Distinct subsystems of a core brain network mediate imagining and remembering. Neuropsychologia, 47, 2222–2238. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.10.026

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T., & Schacter, D. L. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: Common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia, 45, 1363–1377. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.016

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T., & Schacter, D. L. (2008). Age-related changes in the episodic simulation of future events. Psychological Science, 19, 33–41. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02043.x

Atance, C. M., & O’Neill, D. K. (2001). Episodic future thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5, 533–539. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01804-0

Caruso, E. M., Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2008). A wrinkle in time: Asymmetric valuation of past and future events. Psychological Science, 19, 796–801. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02159.x

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavior sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Crovitz, H. F., & Schiffman, H. (1974). Frequency of episodic memories as a function of their age. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 4, 517–518.

D’Argembeau, A., Raffard, S., & Van der Linden, M. (2008). Remembering the past and imagining the future in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 247–251. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.247

D’Argembeau, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2004). Phenomenal characteristics associated with projecting oneself back into the past and forward into the future: Influence of valence and temporal distance. Consciousness and Cognition, 13, 844–858. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2004.07.007

D’Argembeau, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2006). Individual differences in the phenomenology of mental time travel: The effect of vivid visual imagery and emotion regulation strategies. Consciousness and Cognition, 15, 342–350. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2005.09.001

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Vann, S. D., & Maguire, E. A. (2007). Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 1726–1731. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610561104

Hassabis, D., & Maguire, E. A. (2007). Deconstructing episodic memory with construction. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 299–306. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.001

Johnson, M. K., Foley, M. A., Suengas, A. G., & Raye, C. L. (1988). Phenomenal characteristics of memories for perceived and imagined autobiographical events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 117, 371–376. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.117.4.371

Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 3–28. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3

Johnson, M. K., & Raye, C. L. (1981). Reality monitoring. Psychological Review, 88, 67–85. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.88.1.67

Klein, S. B., Loftus, J., & Kihlstrom, J. F. (2002). Memory and temporal experience: The effects of episodic memory loss on an amnesic patient’s ability to remember the past and imagine the future. Social Cognition, 20, 353–379. doi:10.1521/soco.20.5.353.21125

Koriat, A., Bjork, R. A., Sheffer, L., & Bar, S. K. (2004). Predicting one’s own forgetting: The role of experience-based and theory-based processes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133, 643–656. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.133.4.643

McGeoch, J. A. (1932). Forgetting and the law of disuse. Psychological Review, 39, 352–370. doi:10.1037/h0069819

Rubin, D. C. (1980). 51 properties of 125 words: A unit analysis of verbal behavior. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 19, 736–755. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(80)90415-6

Spreng, R. N., & Levine, B. (2006). The temporal distribution of past and future autobiographical events across the lifespan. Memory & Cognition, 34, 1644–1651.

Szpunar, K. K. (2010). Episodic future thought: An emerging concept. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 142–162. doi:10.1177/1745691610362350

Szpunar, K. K., Chan, J. C. K., & McDermott, K. B. (2009). Contextual processing in episodic future thought. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 1539–1548. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn191

Szpunar, K. K., & McDermott, K. B. (2008). Episodic future thought and its relation to remembering: Evidence from ratings of subjective experience. Consciousness and Cognition, 17, 330–334. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2007.04.006

Szpunar, K. K., Watson, J. M., & McDermott, K. B. (2007). Neural substrates of envisioning the future. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 642–647. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610082104

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110, 403–421. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.110.3.403

Tulving. (1985). Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology, 26, 1–12. doi:10.1037/h0080017

Williams, J. M. G., Ellis, N. C., Tyers, C., Healy, H., Rose, G., & MacLeod, A. K. (1996). The specificity of autobiographical memory and imaginability of the future. Memory & Cognition, 24, 116–125.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1271–1288. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1271

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author Note

Portions of these data were presented at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Association for Psychological Science (May 2009) and the 50th Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society (November 2009). The experiments were included as part of the first author’s master’s thesis, under the direction of the second author. We thank Roddy Roediger and Pascal Boyer for serving on the master’s committee and appreciate their helpful comments on this article.

Appendices

Appendix A

Instructions for Experiment 1

In this experiment, you will be describing memories of past episodes of your life and imagining possible future situations that you may encounter. Which memory or future thought you choose to describe is up to you, but I do ask that it be specific. By this I mean you should be able to picture the details of the event that occurred such as where you are, who was there, and what happened during that specific event. In addition, the event should be discrete in time, preferably lasting no more than a couple hours. For instance, if you choose to remember being in a class, choose a specific event that occurred in the class on a specific day, rather than describing the class in general. Your memory could be about a specific test. You could describe where you were, who was around you, how the test made you feel. Maybe you remember struggling with a question or the person to your right making annoying clicking noises. For a future event, you could imagine a specific event where you are driving a car in the future such as driving to a specific restaurant with a few friends, instead of imagining driving a car in general in the future. What will it be like in the car, what will you see out the window, who will be there, what will be on the radio?

Although you can choose any memory or future thought, please try to choose memories that occurred [(a) within the past day, (b) approximately 1 week ago, (c) approximately 1 year ago, (d) approximately 5 years ago, (e) approximately 10 years ago] and future thoughts that occur [(a) within 1 day from now, (b) approximately 1 week from now, (c) approximately 1 year from now, (d) approximately 5 years from now, (e) approximately 10 years from now]. It is important to try your best to remember events that occurred within this time frame and future events that could occur within this specific time frame. [(For d and e:) Go ahead and think about how old your were [(d) 5 years ago, (e) 10 years ago] and how old you will be [(d) 5 years from now, (e) 10 years from now.]

On each trial a screen will appear that tells you whether to remember a past event or to imagine a future event. Also, a word (such as zoo) will appear on the screen that can help you think of a memory or future event. Although the word is useful, it is not important that your memory or future event be related to the word in any way. It is only a tool provided to help you. Instead, use the first memory or future event that comes to mind. As soon as you have a memory or future thought in mind, press the space bar. The screen will then turn green for 3 minutes. While the screen is green, describe your memory or future thought in the blue books provided for you. You can use both sides of the paper. Try to write as much detail as possible. In particular, write in as much detail as possible everything you can remember or imagine about where you are and who and what is around you. Also write any other details that come to mind. Continue to write as much as you can until the screen turns from green to red. When the screen turns red, stop writing.

After each memory and future thought, you will be asked a series of questions about your future thought and memory. Each question will ask you to rate some quality on a scale from 1 to 7. When the questions are over, the next trial will begin. Past and future trials will occur in a random order so be prepared to switch back and forth. Before you begin describing each memory or future event, please write on the top of the page either “past” or “future” to indicate which kind of trial it is and write the cue word that was provided. Also, on each new trial, please turn to a new page to begin writing.

Appendix B

Sample Past and Future Written Protocols

Past – 1 day – window

My room is always hot to other people, but I find it perfectly comfortable. My boyfriend came over to study and hang out and we ended up watching a movie on television. He kept complaining about how hot he was, so he drank all of the water, lemonade, and juice that I had in my fridge to cool off. I offered to turn down the thermostat, but he wouldn’t let me. Instead he opens the window on the side of the futon where he is laying. So, now I have to get a blanket because the air makes me too cold.

Future – 10 years – dress

I am my friend’s maid of honor at her wedding, and I am wearing a black dress that I got to pick for myself. It is time to make toasts, and I stand. I talk about our lives together, how we are practically sisters. We both cry. The room is dim and lovely, and she looks beautiful. I am nervous making speeches, but I’ve had champagne so I am more comfortable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arnold, K.M., McDermott, K.B. & Szpunar, K.K. Imagining the near and far future: The role of location familiarity. Mem Cogn 39, 954–967 (2011). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-011-0076-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-011-0076-1